Athena

Attic black-figure tripod showing the birth of Athena, the daughter of Zeus and the Oceanid Metis, from the head of Zeus. Attributed to the C Painter (ca. 570–260 BCE). Found in Thebes.

Louvre Museum, Paris / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainOverview

Athena was the goddess associated with wisdom, craftwork, and war. As one of the Twelve Olympians and the patron goddess of Athens, she lent her favor and guidance to many famous Greek heroes.

In myth, Athena was typically characterized by her intelligence and tact, though some stories emphasized her more destructive passions, such as her terrible anger.

The heart of Athena’s cult was in Athens. This was the site of her greatest sanctuaries, including the famous Parthenon. The Athenians also celebrated lavish festivals in honor of Athena, such as the Panathenaea.

Key Facts

How was Athena born?

Athena was the daughter of Zeus, the king of the gods, and his first wife, the Oceanid Metis. But the precise circumstances of Athena’s birth were unusual. In the familiar tradition, Zeus heard a prophecy that his wife was destined to bear a child who would overthrow him. To prevent this, Zeus swallowed Metis before she could give birth.

But Metis was already pregnant with Athena, and the goddess eventually sprang forth from her father’s forehead, fully grown and wearing armor. It was thus often said that Athena had no mother, having been birthed by her father Zeus alone.

Attic black-figure tripod showing the birth of Athena, the daughter of Zeus and the Oceanid Metis, from the head of Zeus. Attributed to the C Painter (ca. 570–260 BCE). Found in Thebes.

Louvre Museum, Paris / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainWhat were Athena’s attributes?

A virgin goddess, Athena usually appeared decked out for war, with helmet, shield, and spear. She was often accompanied by her favorite animal, the owl. In literature especially, Athena also carried the aegis, an impervious shield, and bore the Gorgon’s head on her armor.

In the midst of war—where she was most commonly depicted—Athena embodied rationality, tactics, and strategy. Her cold logic stood in direct contrast to her brother Ares’ rage, violence, and impulsiveness.

The "Varvakeion Athena" (first half of the third century CE), after the Athena Parthenos by Phidias

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / George E. KoronaiosCC BY-SA 4.0Where was Athena worshipped?

While Athena was broadly worshipped throughout the Greek world, her cult was particularly strong in Athens. There the goddess was commemorated via the construction of several public buildings, including the famed Parthenon on the Acropolis. The Athenians also celebrated extravagant festivals in honor of Athena, such as the Panathenaea, which involved processions, sacrifices, and athletic games.

Photo of the ruins of the Parthenon in Athens

Steve SwayneCC BY 2.0The Contest for Athens

An important Athenian myth told of how, early in the city’s mythical past, Athena and Poseidon competed for the right to become the patron god of Athens. Each god presented the people with a gift: Poseidon struck the ground with his trident and brought forth a stream, while Athena produced the first olive tree. The Athenians chose Athena, and Athens remained her city thereafter.

Poseidon and Athena Battle for Control of Athens by Benvenuto Tisi (1512)

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, DresdenPublic DomainEtymology

Scholars have debated the origin of the name “Athena” since the time of Plato; his dialogue Cratylus contained a rare and lengthy discussion of the history of the name. Speaking through the figure of Socrates, Plato attributed the name’s origin to Homer, who had cobbled it together from the Greek words nous (“mind”) and dianoia (“intelligence”). As Plato put it: “The maker of names [Homer] appears to have had a singular notion about her, and indeed calls her by a still higher title, ‘divine intelligence’ (theou noēsis).”[1]

Though Plato’s discussion of Homer provides some insight into Athena’s esteemed reputation, this explanation for her name is almost certainly incorrect. According to the best available evidence, the name “Athena” is connected to Athēnai, the Greek name for the city of Athens.

In a kind of “chicken-or-egg” dilemma, scholars have debated whether the city was named for the goddess or the goddess for the city; nowadays, however, it is generally believed that the goddess Athena took her name from the city of Athens.[2] This is probably why the goddess does not have an individual name in the earliest texts from ancient Greece (Mycenaean inscriptions from the Bronze Age), in which she is called simply a-ta-na po-ti-ni-ja—“Lady” or “Mistress of Athens.”

Such a naming scheme was not uncommon among the ancient polytheists, who frequently named deities after the places with which they were most commonly associated. Unfortunately, the origins of the word Athēnai are shrouded in mystery: the root is neither Greek nor Indo-European.[3] Thus, the meaning of the name “Athena” remains unclear.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Athena Ἀθήνη Phonetic

IPA

[uh-THEE-nuh] /əˈθi nə/

Other Names

Athena’s name is sometimes transliterated as Athene [uh-THEE-nee] rather than Athena. The ancient Greeks also called the goddess Pallas Athena or simply Pallas.

Epithets

Athena was called many things. Perhaps her most common epithet (which sometimes functioned as an alternate name) was Pallas. The origins of this title are ancient and obscure and became much intertwined with Athena’s mythos (see below).

Athena’s other important titles included Parthenos (“virgin”), Promachos (“she who fights in the front”), and Erganē (“of the crafts”). In Athens, the city with which she was most intimately connected, Athena was often simply called “the goddess.”

In literature, one of Athena’s most common epithets was Glaukōpis, usually translated as “bright-eyed” or “gray-eyed” (Glaukōpis is derived from the Greek words for “face” and “owl,” Athena’s bird). Athena was also frequently called Tritogeneia (likely meaning “Triton-born”), a name that may indicate that in some early versions of her myth the sea god Triton was her father or foster father.

Attributes

In art, Athena was often depicted in full armor. Medusa’s head was almost always part of this armor, displayed on Athena’s breastplate or on her shield, the aegis. Thus clad for war, Athena could be seen in the company of the heroes she loved and supported.

Athena was also often pictured in the company of olives and owls. Indeed, Athena was most commonly associated with the clever and sharp-eyed owl (this is probably the basis of Athena’s epithet Glaukōpis, explained above).

Greek bronze statuette of Athena with an owl (ca. 460 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainFamily

According to the most popular mythologies surrounding her, Athena was born (or, perhaps more accurately, emerged) from the union of Zeus and his first wife, Metis. She was their only child.[4]

Soon after Metis became pregnant, Zeus heard a prophecy foretelling his downfall at the hands of his own child. Fearful of his impending doom, Zeus swallowed Metis and her child, just as his own father, Cronus, had swallowed Zeus’ brothers and sisters—Demeter, Hades, Hera, Hestia, and Poseidon.

Minerva Born from the Head of Jupiter by René-Antoine Houasse (before 1688). Palace of Versailles.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe child within Metis, however, would not be denied. One day, Athena suddenly burst forth from Zeus’ forehead. She was fully grown, armed with a spear, and dressed in her battle armor. Some accounts featured Hephaestus, Prometheus, or another mythical figure serving as a midwife of sorts by prying open Zeus’ head with an axe.[5] This moment was commonly depicted in ancient art and has been the subject of more recent pieces as well.

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

- Metis

Siblings

Brothers

Sisters

Mythology

Greek mythology, especially the lore surrounding the founding and history of Athens, was rich with stories of Athena. While certain figures from the Mycenaean era paralleled Athena in her essential attributes, traditional conceptions of Athena evolved during the Greek classical period (490–323 BCE). She was later worshipped by the Romans as the deity Minerva. Her longevity among the Greeks and Hellenized peoples suggests that they greatly admired the qualities of wisdom, perspicuity, and forethought with which Athena was associated.

Athena and Pallas

The story of how Athena acquired the additional name Pallas was already lost to history in ancient times; the Greeks did, however, devise myths to explain Athena’s double name. There were several versions of this aetiological (i.e., explanatory) myth.

In one version, Pallas was a close childhood friend of Athena. One day, while they were playing, Athena killed Pallas by accident. She was heartbroken. To honor her dead friend, she took the name Pallas for herself. She also carved a wooden image of Pallas, called the Palladium, which was said to guarantee the invincibility of the city that possessed it (in various traditions, the Palladium was said to be in Troy or even Rome).[6]

In another version, Pallas was one of the Giants whom the Olympians battled in the Gigantomachy. After killing Pallas in combat, Athena flayed him and wore his invulnerable skin as armor.[7]

In yet another (even more obscure) version of the story, the Pallas in question was not a Giant but Athena’s own father (in this tradition, apparently, Athena was not Zeus’ daughter). When Pallas attempted to violate Athena, she killed and flayed him.[8]

Athena and the Founding of Athens

A common thread in Athena’s mythos was how she came to be the patron of the city of Athens. One myth claimed that she and Poseidon competed for the honor in the early days of the polis. The two deities each decided to bestow a gift upon the Athenians and agreed to let a judge select the best (sources disagree on the identity of the judge/judges: some say it was the king of Athens, others that it was the Olympian gods).

In most versions, Poseidon thrust his trident into the ground, unleashing a torrent of salt water as a gift. In Roman versions, he brought the first horses to the Athenians.[9] Athena, meanwhile, offered the first olive tree. Olives quickly became a staple of the Athenian diet, and the tree itself became the foundation of the city’s economic success in the form of lucrative oil exports. Athena was chosen as the winner, thus inaugurating a lasting relationship between the deity and the city. Poseidon, angry at having lost, flooded much of the surrounding region of Attica.

Known as Athena Parthenos (“virgin”), she avoided the erotic entanglements and sexual controversies that ensnared the other gods and goddesses. There was, however, one important exception to this rule—one that builds on Athena’s reputation as founder and protector of Athens.

There were two broad versions of this myth. In one, Hephaestus attempted to rape Athena, but she pulled herself away from her assaulter, causing him to ejaculate on her thigh. Athena wiped his seed off with a tuft of wool and threw it on the ground. This action impregnated Gaia, the earth goddess, who gave life to Erichthonius, one of the early, legendary rulers of Athens.[10] Erichthonius would also become one of the central figures in Athenian festivals celebrating the origins of the city.

In another version of this story, Hephaestus, claiming his privilege as Athena’s axe-wielding midwife, persuaded Zeus to consent to a marriage between Athena and himself. Though they were married, Athena stole away from the marriage bed and left Hephaestus to ejaculate on the floor. As in the other version of this myth, his seed then impregnated Gaia and led to the conception of Erichthonius.[11]

Athena receives the baby Erichthonius from Gaia, on a fragment of a kylix, or a drinking cup (5th century BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainFrom here, the story meanders in unexpected directions. Once Erichthonius was born, Athena placed him in a chest and entrusted it to the three daughters of Cecrops—Herse, Pandrosus, and Aglaurus—telling them not to look inside. When curiosity got the better of them, the sisters opened the container, only to find a coiled snake.

Other stories claimed that there was a child guarded by a snake in the chest, or that the child’s legs had been transformed into a serpent’s tail. The sisters were subsequently either attacked and killed by the snake or, in other versions, were driven mad by the horrific sight and threw themselves from the Acropolis, the hilltop fortress of Athens.[12]

In artistic representations, Athena was sometimes depicted alongside the snake. Legend soon established this serpent as a protector of Athens.

A Goddess’s Wrath: Four Tales of Athena’s Vengeance

Like the other Olympian gods, Athena could be benevolent but also extremely cruel. She was especially harsh in punishing those that offended her, and there are several myths that attest to the potency of her vengeance.

Arachne

One example of Athena’s anger is the myth of Arachne. Though this myth has become quite famous, it was not well known in antiquity. Virtually the only source for it is the Roman poet Ovid, who wrote in the late first century BCE and early first century CE. According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Arachne was a weaver who lived in Lydia. Her skill earned her great fame, which caused her to become conceited—so conceited, in fact, that Arachne challenged Athena herself to a weaving contest.

During the contest, Arachne chose to weave a tapestry of myths in which the gods debased themselves or were humiliated. Athena, horrified by this insult, destroyed Arachne’s work and beat her with her distaff. Arachne then hanged herself out of shame. Pitying the poor girl, Athena transformed Arachne into a spider who constantly wove her silken web.[13]

Tiresias

In another myth, recounted by the third-century BCE poet Callimachus, Athena was bathing in a river on Mount Helicon one day. She was attended by one of her close friends, the nymph Chariclo. Tiresias, Chariclo’s son, happened to be hunting nearby and unfortunately stumbled upon Athena as she bathed. Athena was horrified that a mortal had seen her naked and struck Tiresias blind as punishment. Chariclo, however, begged Athena for mercy; softened by her friend’s pleas, Athena gave Tiresias the gift of prophecy to make up for his lost eyesight.[14]

Marsyas

Athena was also indirectly responsible for the terrible fate suffered by the satyr Marsyas. As early as the fifth century BCE, Athena was said to have invented the aulos, a Greek instrument resembling the flute.[15] Some traditions, however, claim that when Athena saw how silly she looked while playing the aulos—she happened to catch a glimpse of her reflection in a pool of water—she threw away the instrument and cursed anybody who picked it up.[16]

Ignorant of the curse, an unsuspecting satyr named Marsyas picked up the instrument and became a virtuoso player. He eventually became so skilled that he challenged Apollo himself, the god of music and the arts, to a music competition. Though he played beautifully, Marsyas’ audacity angered Apollo, who had him skinned alive for his trouble.

Medusa

In later sources, Athena was also connected to the myth of Medusa. According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Medusa was originally a beautiful maiden. She was so beautiful, in fact, that the sea god Poseidon fell in love with her and slept with her in a temple of Athena.

The virginal Athena did not appreciate this act of sacrilege, and, rather capriciously, decided to punish Medusa rather than Poseidon: she transformed Medusa’s lovely hair into snakes and made it so that anybody who looked upon her was immediately turned to stone.[17] Later, to add insult to injury, she helped Perseus in his quest to kill Medusa.

Athena, the Benefactress of Heroes

Athena appeared often in Greek mythology as a champion of heroes such as Argos, Perseus, and Heracles. These stories celebrated Athena’s kind regard for struggling mortals and often displayed her craftiness and ingenuity. For example, Athena advised Argos on how to construct the Argo, the ship that took Jason and the Argonauts to find the Golden Fleece.

A painted terracotta bowl depicts Athena, center, as she accompanies Jason reaching for the Golden Fleece. A third figure at right prepares to board the ship Argo (ca. 570–60 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAthena played a larger role in the myth of Perseus, whom she aided in his quest to slay Medusa, the Gorgon with hair made of serpents whose gaze turned onlookers to stone. As he set out on his quest, Athena appeared before him and gave him a bronze shield, polished to reflect the sight of Medusa so that Perseus would not have to look in her eyes.

Athena was also involved in the myth of Bellerophon, the son of Poseidon who killed the Chimera. According to the poet Pindar, Athena was the one who taught Bellerophon how to tame and ride the immortal winged horse Pegasus.[18]

Even the great Heracles benefitted from Athena’s intervention; she came to his aid when he was ordered to steal the golden apples from Hera’s secret garden, which was overseen by the daughters of Atlas. Atlas, a Titan, had been sentenced to hold up the sky for all eternity after losing to Zeus in the great war between the gods and the Titans. Heracles, in order to complete his task, offered to hold the sky while Atlas beseeched his daughters to gather the apples.

When the sky proved too heavy for the mighty Heracles, Athena took action and lifted it so that he would not be crushed under its weight. This scene was sometimes represented in artistic representations of this labor.

Athena in the Iliad and Odyssey

Athena played central roles in Homer’s epic poems. Long before the events of the Iliad, Hera, Aphrodite, and Athena each claimed to be the fairest of all the goddesses. They commissioned Paris, prince of Troy, to judge which of them was truly the most beautiful.

Each of the goddesses tried to bribe him—Hera promised political power, Athena offered the glories of military triumph, and Aphrodite agreed to allow Paris to marry the most beautiful woman alive. Paris chose the latter gift, which happened to be Helen, wife of Menelaus, the king of Sparta. It was Helen’s abduction that sparked the Trojan War.

In the Iliad, it is implied that Athena and Hera’s hatred of the Trojans resulted from the insult they had received in the Judgment of Paris. These two goddesses thus emerged as the most committed and consistent allies of the Greeks in the Iliad as they assailed and ultimately conquered Troy.

Often Athena’s assistance took the form of wisdom whispered softly to foolhardy mortals. She paid special attention to Achilles, whose rage toward Agamemnon threatened to undo the tenuous Greek alliance. As Achilles prepared to draw his sword and kill Agamemnon, Athena appeared, saying:

I have come from heaven to stay your anger, if you will obey, The goddess white-armed Hera sent me forth, for in her heart she loves and cares for both of you. But come, cease from strife, and do not grasp the sword with your hand. With words indeed taunt him, telling him how it shall be. For thus will I speak, and this thing shall truly be brought to pass. Hereafter three times as many glorious gifts shall be yours on account of this arrogance. But refrain, and obey us.[19]

Later in the war, the two sides decided that the conflict might be best determined through single combat between Menelaus and Paris. Athena was anxious to resume the fighting, however, and disguised herself as a Trojan soldier named Laodocus.

In this guise, she persuaded a general and Trojan ally called Pandaros to fire an arrow at Menelaus, promising that the death of the Spartan king would end the conflict. When Pandaros fired, Athena altered the path of the projectile, ensuring that it would only injure Menelaus. This treacherous violation of the truce proved ample reason to cancel it altogether. Thus, the war continued.

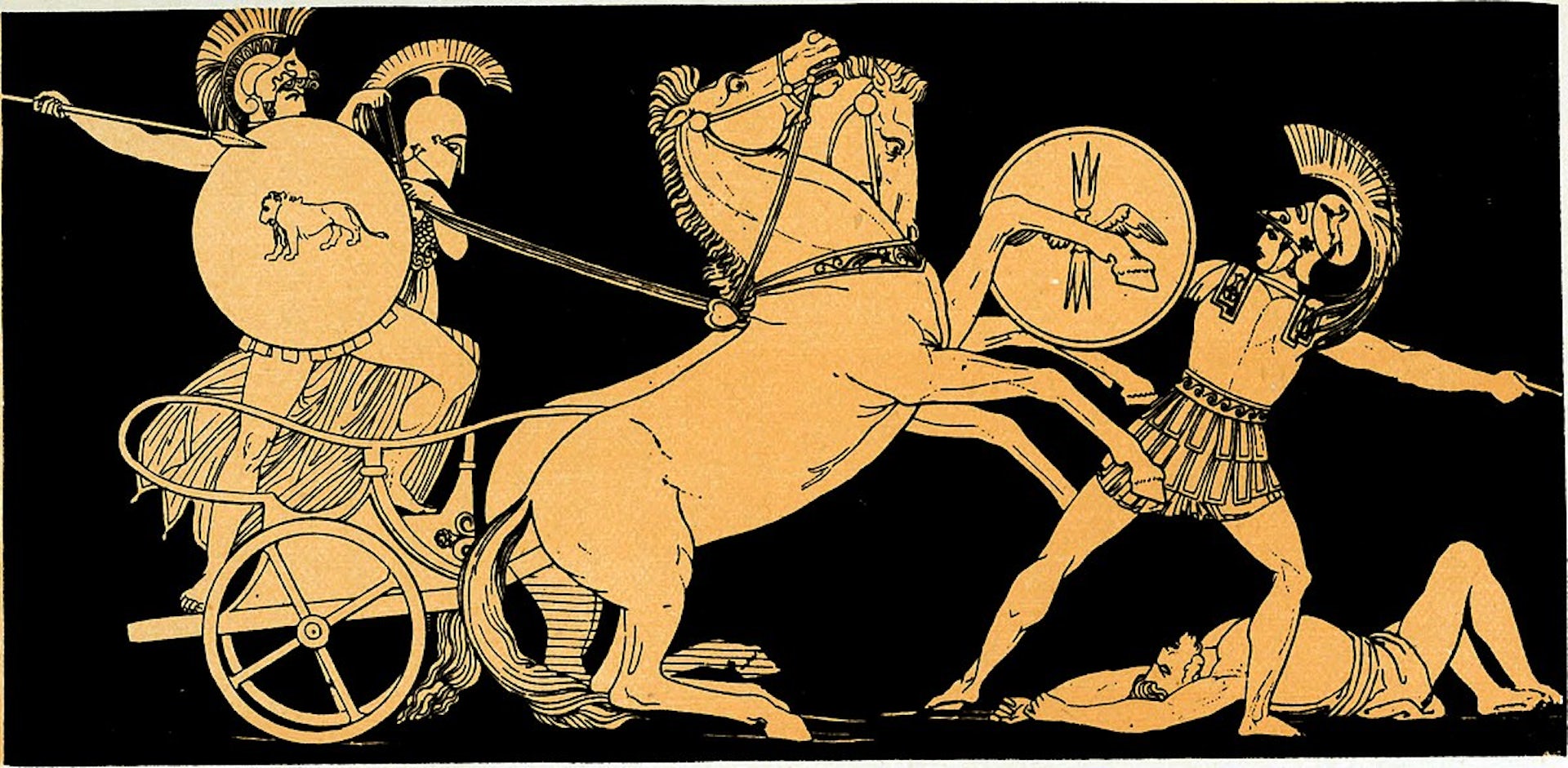

Athena would again exert decisive influence over the conflict when she championed the warrior Diomedes, granting him strength and courage to lead the battle against the Trojans. When they confronted Ares, who was full of rage and lust for blood, she guided Diomedes as he thrust his spear into the god, leaving him injured and disabled on the battlefield.

Diomed [i.e., Diomedes] Casting his Spear Against Ares by John Flaxman (1895).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn the Odyssey, Athena offered wisdom and succor to the embattled Odysseus and his son Telemachus. As Odysseus began his long journey home following the conclusion of the Trojan War, Athena inspired wise thoughts within his mind. In Ithaca, Odysseus’ home, she gave counsel to Telemachus, urging the young man to seek out information about his father.

Only later did Athena appear to Odysseus in person: when he finally returned to Ithaca, she came to him disguised as a shepherd. To stoke his rage, Athena told him that Penelope had moved on—assuming that Odysseus had died, she had taken another husband.

Trusting in his wife’s fidelity, Odysseus refused to believe the trickster. When Athena saw that she could not fool the shrewd Odysseus, she revealed her true identity to him. Athena then told him the truth: Penelope was besieged by suitors hoping to claim what was rightfully Odysseus’, but she remained true while awaiting his return. Athena then disguised Odysseus as a beggar. So costumed, Odysseus slayed the suitors and reclaimed his wife and home.

Worship

Athena was worshipped throughout the Greek world, but her most important cult centers were in the cities of Athens and Sparta.

Temples

Athena was honored with the Parthenon, a huge temple on the Athenian Acropolis (the hilltop fortress and religious center of the city). Built in the fifth century BCE, during the “Golden Age” of Athens, it is arguably the most famous example of ancient Greek architecture. The Parthenon was decorated with beautiful sculptures and friezes, including an enormous cult statue of Athena—called the statue of Athena Parthenos—that stood nearly forty feet tall. Fashioned out of ivory and gold by the renowned sculptor Pheidias, the statue was unfortunately lost or destroyed long ago.

There were other smaller temples of Athena in Athens, including the elegant Temple of Athena Nike (that is, Athena as goddess of victory).

Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis in Athens (ca. 420 BCE).

Andy HayCC BY 2.0Athena also had a great temple of the Acropolis of Sparta. This temple, known as the Bronze House, was said to have been built by the mythical king Tyndareus and his sons Castor and Polydeuces.[20] The Bronze House became infamous when, in the fifth century BCE, the Spartans killed the traitorous general Pausanias by trapping him inside. This act of sacrilege was said to have incurred the wrath of Athena. The episode and its aftermath were described by the historian Thucydides, among others.[21]

Festivals

The grandest and most important festival of Athena was the Panathenaea. This festival was celebrated in Athens every year, with an even more elaborate version, called the Great Panathenaea, held every four years. The Panathenaea consisted of a procession of young men and women, sacrifices, and athletic games. The festival culminated in the grooming of Athena’s cult statue: the statue was undressed, washed in seawater, and then clothed in a beautiful new robe (called a peplos) woven by the women of Athens.

Similar festivals were held in other Greek cities as well. In Boeotia, there was a Panathenaea-like festival called the Pamboeotia, but relatively little is known about it.

In Athens, Athena’s namesake and religious birthplace, the goddess was also honored during the Synoikia. This festival commemorated the ancient unification of the region of Attica and included sacrifices to Athena.

Pop Culture

Athena has made numerous appearances in popular culture. In the television series Xena: Warrior Princess, for example, Athena is an important character, portrayed by Paris Jefferson. Athena is also prominent in the God of War video game series, where she advises and aids the main protagonist, Kratos, in his quests.

Athena adorns the California state seal, seen here as a mosaic on the floor of the San Mateo County History Museum in Redwood City.

Mark DolinerCC BY-SA 2.0Athena is also featured on the state seal of California. In this depiction, she is shown wearing armor and carrying her spear and shield while looking over a body of water, presumed to be San Francisco Bay.