Pegasus

Minerva restrains Pegasus with the help of Mercury by Jan Boeckhorst (ca. 1650–54).

Noordbrabants MuseumPublic DomainOverview

Pegasus, an immortal winged horse, was born when Perseus beheaded Medusa; he emerged from the Gorgon’s blood along with the Giant Chrysaor. Eventually, Pegasus was tamed and bridled by the Corinthian hero Bellerophon, and together they fought and killed the monstrous, fire-breathing Chimera.

In some traditions, Bellerophon grew arrogant because of his successes and tried to ride Pegasus to the home of the gods on Olympus. But Pegasus threw Bellerophon from his back, and the hero was gravely injured or killed (depending on the version).

Pegasus was sometimes said to be the thunder-bearer of Zeus himself. He was also associated with the Muses. The constellation Pegasus was created in the heavens to honor him.

Etymology

According to the poet Hesiod, who described the birth of Pegasus in his Theogony, the name “Pegasus” was derived from the Greek word pēgē, meaning “spring,” because he had been born “near the springs [pēgai] of Ocean.”[1]

Modern scholars have suggested other possible origins for the name. Some have connected Pegasus to the stem *piḫašš-, which means “lightning” or possibly “strength” in the Luwian language spoken in ancient Anatolia. This stem is attested in the name of the Anatolian weather god Pihassasi, who was responsible for thunder and lightning. Since Pegasus was often imagined as the thunder-bearer of Zeus, it has been suggested that Pegasus’ myth and name were derived from Pihassasi.[2]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Pegasus Πήγασος Phonetic

IPA

[PEG-uh-suhs] /ˈpɛg ə səs/

Attributes and Iconography

Locales

Pegasus roamed far and wide throughout the cosmos. He had especially close ties with springs such as the Hippocrene, the spring of the Muses, and the Peirene, where he was eventually captured and tamed by Bellerophon. In other myths, Pegasus made his abode with the gods on Mount Olympus, where he served as Zeus’ thunder-bearer.

Appearance

Pegasus was a horse who had the ability to fly. In literature and the visual arts, Pegasus was almost always represented with wings, but in some rare cases he appeared as an ordinary horse.[3] Over time, it became increasingly common to depict Pegasus as pristinely white.

Attic epinetron showing Pegasus, Bellerophon, and the Chimera (ca. 425–420 BCE). National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

MarsyasCC BY-SA 2.0Pegasus was usually imagined as an immortal being, and many ancient sources associated him with a constellation in the night sky that was eventually named after him.

Iconography

In ancient art, Pegasus was most often depicted with Bellerophon, either flying or battling the Chimera. He was an especially popular subject for the vase painters of Corinth, Bellerophon’s hometown.[4]

Family

Pegasus’ mother was Medusa, from whose blood he was born. His father was usually said to be Poseidon, who had been Medusa’s lover.

Pegasus’ brother was the Giant Chrysaor. Chrysaor’s son—and thus Pegasus’ nephew—was Geryon, a monster with three bodies who was slain by Heracles.

Mythology

Origins

The Gorgon Medusa, whose gaze famously turned humans to stone, was once a lover of the sea god Poseidon. When Perseus, the hero of Argos, beheaded Medusa, Pegasus was born from her blood, together with the Giant Chrysaor. Poseidon was usually named as the father of both creatures, even if the mechanics of his paternity were obscure at best.[5]

In one myth, Pegasus’ great hoof struck the ground on Mount Helicon, the sacred home of the Muses, and created a spring called the Hippocrene.[6] For hundreds of years, Greek and Roman poets regarded the waters of the Hippocrene as a source of divine inspiration.

Fragment of a terracotta volute-krater depicting Pegasus; an arm, possibly Bellerophon's, can be seen holding the reins. Attributed to the Painter of the Dublin Situlae (mid-4th century BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBellerophon

In antiquity, Pegasus was best known for the role he played in the mythos of Bellerophon. Like Pegasus, Bellerophon was a son of Poseidon (making him and the winged horse half-brothers). Bellerophon was from the Greek city of Corinth but was forced to leave due to a crime he had committed (the exact nature of the crime varies in different traditions).

Bellerophon’s travels took him to Lydia, where the king, Iobates, dispatched him to kill the Chimera. The Chimera was a hybrid monster with a lion’s head in front, a serpent for a tail, and a fire-breathing goat head growing out of its middle.

Bellerophon knew he would never stand a chance against the Chimera without some sort of divine assistance. In some traditions, Bellerophon’s father, Poseidon, gave him Pegasus to help him in his battle with the Chimera.[7] But according to the more familiar version, Bellerophon consulted the prophet Polyidus, who told him to sleep in the temple of Athena. There, Athena appeared to him in a dream. According to the poet Pindar, who narrated the story in detail,

the maiden Pallas brought to [Bellerophon] a bridle with golden cheek-pieces. The dream suddenly became waking reality, and she spoke: “Are you sleeping, king, son of Aeolus? Come, take this charm for the horse; and, sacrificing a white bull, show it to your ancestor, Poseidon the Horse-Tamer.”[8]

When Bellerophon awoke, he saw that Athena had left him a golden bridle. He located Pegasus by the spring of Peirene in Corinth and easily rode him with the aid of this golden bridle. With the help of Pegasus, Bellerophon was able to defeat the Chimera as well as other foes, including the Solymi and the Amazons.[9]

However, Bellerophon soon started using Pegasus for unjust personal agendas. According to Euripides’ lost tragedy Stheneboea, Bellerophon wanted to avenge himself against Stheneboea, a queen of Argos who had once accused him of trying to seduce her. This accusation had caused Bellerophon to lose the friendship of Stheneboea’s husband, Proetus, the king of Argos. Once he had Pegasus, Bellerophon tricked Stheneboea into taking a ride with him, then threw her off as the winged horse was flying over the sea.[10]

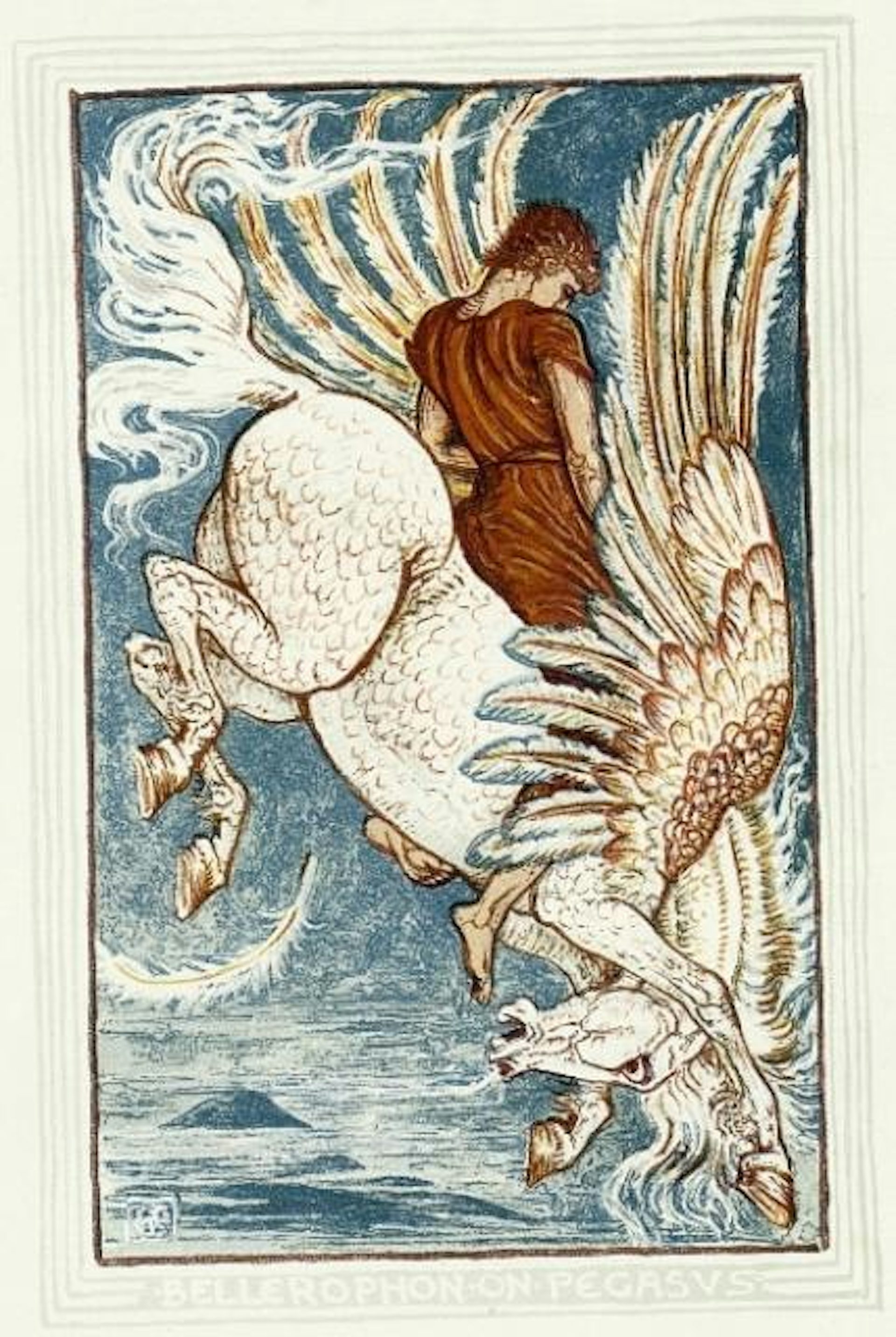

Bellerophon on Pegasus by Walter Crane (1892).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainEventually, Bellerophon’s cruelty and arrogance led to his (literal) downfall. In the common tradition, Bellerophon was so proud of his successes that he decided he deserved to live among the gods on Olympus. He tried to ride Pegasus to the mountaintop, but the horse buckled—some say Zeus sent a gadfly to sting him—and threw Bellerophon.[11] According to some traditions, he was killed by the fall,[12] but in the most familiar version he simply became crippled and was never able to carry out heroic deeds again.[13]

Pegasus on Olympus

While Bellerophon fell from grace, Pegasus ascended to the heavens and lived among the gods. In fact, according to Hesiod, Pegasus first flew to Olympus soon after he was born: “Now Pegasus flew away and left the earth, the mother of flocks, and came to the deathless gods: and he dwells in the house of Zeus and brings to wise Zeus the thunder and lightning.”[14]

As thunder-bearer of Zeus, Pegasus was showered with honors. He also earned the love of the Muses when he created the Hippocrene spring. The great winged horse was commemorated in the night sky as the constellation Pegasus.

Pop Culture

Pegasus has had a pervasive afterlife in modern pop culture. He has appeared in numerous films, including Fantasia (1940), Hercules (1997), and Clash of the Titans (the 1981 original as well as the 2010 remake).

He is frequently mentioned in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, where is the father of other winged horses.

Pegasus has appeared in or been adapted for various video games—among them, God of War and Age of Mythology.

Finally, Pegasus has been widely exploited by the commercial sector and now graces the logos of various companies, schools, and public organizations across the world.