Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux)

Leda and the Swan by Jacques Sarazin (ca. 1640–1650)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Castor and Pollux (or Polydeuces)—also known as the Dioscuri—were heroic twin brothers from Sparta. They were both sons of Leda, the queen of Sparta, though they had different fathers: Castor’s father was Leda’s husband Tyndareus, while Pollux’s father was Zeus, the king of the gods.

The Dioscuri participated in a number of important heroic exploits, including the voyage of the Argonauts and the Calydonian Boar Hunt. They also saved their sister Helen when she was abducted by the Athenian king Theseus.

One or both of the Dioscuri lost their lives in a battle with their rivals, the twins Idas and Lynceus. But Zeus granted them a qualified immortality, allowing them to alternate days between the Underworld and the heavens. As a result, the Dioscuri came to be regarded as gods throughout Greece.

Worship of the Dioscuri eventually spread to Italy and Rome, where they were known as the Castores and became identified with the constellation Gemini.

Key Facts

Who were the Dioscuri’s parents?

The Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, were twin brothers. But according to the best-known tradition, they had different fathers: Castor was the son of Leda and her husband Tyndareus, the king of Sparta, while Pollux was the son of Zeus, who had slept with Leda in the form of a swan.

There were, however, other versions of the Dioscuri’s parentage. Sometimes both brothers were considered the sons of Tyndareus; other times, both were the sons of Zeus. In one tradition, they may have even been the sons of Zeus and Nemesis, the goddess of retribution, rather than Leda.

Leda and the Swan by Jacques Sarazin (ca. 1640–1650)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhat were the Dioscuri’s attributes?

The Dioscuri were universally represented as youthful warriors, closely associated with horses. As gods, they were believed to be the patrons of sailors, to whom they appeared as St. Elmo’s fire—a glowing electric field that commonly occurs during thunderstorms.

Each of the Dioscuri had distinguishing attributes of their own as well. Castor was a great fencer, while Pollux was a champion boxer.

Roman statuettes of Castor and Pollux (1st half of the 3rd century CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Ad MeskensCC BY-SA 3.0How did the Dioscuri die?

In most accounts, the Dioscuri were killed during a battle with Idas and Lynceus, twin brothers from Messenia who were their chief rivals. One popular tradition traced this battle to a quarrel over the daughters of Leucippus, who were supposed to marry Idas and Lynceus but who were abducted by the Dioscuri instead. A fierce fight broke out between the two sets of twins, during which Castor, Idas, and Lynceus were all killed.

Pollux, who was the son of Zeus, begged his father not to let him be separated from his dead brother. Zeus responded by making Castor and Pollux immortal on alternating days: they would live among the gods on Mount Olympus one day, then dwell among the dead in the Underworld the next.

Roman sarcophagus showing the rape of the Leucippides by the Dioscuri (ca. 160 CE)

Vatican Museums / JastrowPublic DomainThe Dioscuri Rescue Helen

When their sister Helen was abducted by the Athenian king Theseus, Castor and Pollux were the ones who rescued her. They invaded Attica (the region controlled by Theseus) while Theseus was busy in the Underworld with his friend Pirithous.

The divine twins quickly overcame the Attic forces, discovered where their sister was being held, and brought her back home. They even captured Aethra, Theseus’ mother, and forced her to become Helen’s servant.

Castor and Pollux Rescuing Helen by Jean-Bruno Gassies (1817)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainRoles and Powers

For the Greeks and Romans (and a few other cultures, too), the Dioscuri were not only heroes but also gods. Because of this, they were assigned important roles and powers, just like any other god.

The Dioscuri were broadly viewed as helper gods, but they were especially connected with sailors and sea travel. They were believed to appear to sailors in distress as St. Elmo’s fire—an electrical phenomenon that forms around rod-like objects (such as a ship’s mast) during thunderstorms.[1]

Roman literature also highlighted the twins’ role as protectors of sailors. Ovid described Castor and Pollux as “stars [...] helpful to the storm-tossed bark.”[2] Horace wrote that they had the power to pull up sunken ships from the bottom of the sea.[3] Hyginus, meanwhile, claimed that Neptune, the principal god of the sea, had granted Castor and Pollux the power to rescue castaways.[4]

The Dioscuri were also helpers in wartime. In the Greek city-state of Sparta, where the twins were thought to have been born (and where their cult was therefore extremely important), the Dioscuri were regarded as military innovators who invented the armed war dance and the attack formation (named “castor” in their honor).[5] It was said that when one of the two kings of Sparta stayed at home during a war, one of the Dioscuri stayed behind, too.[6]

Castor and Pollux by Robert Fagan (between 1793 and 1795)

National TrustPublic DomainThere were a few cases in antiquity when the Dioscuri supposedly showed up to fight alongside their devotees. In one story, they arrived riding white steeds to help the Greek Locrians of Italy in a battle along the Sagra River.[7] But a much more famous account told of how the Dioscuri came to help the Romans (who knew them as the Castores) at the Battle of Lake Regillus in 496 BCE (see below).

Other roles and powers were occasionally assigned to the Dioscuri as well. For example, they were sometimes viewed as psychopompic deities—that is, deities responsible for conveying the souls of the dead to the Underworld.[8]

In Rome, Castor and Pollux were closely associated with water deities, such as the nymph Juturna—in whose spring they were said to have watered their horses after the Battle of Lake Regillus—and the sea god Neptune. The Romans also frequently invoked Castor and Pollux in oaths.

Attributes

The Dioscuri were divine twins, connected above all with the Greek city-state of Sparta. They had counterparts both within the Greek world (e.g., Amphion and Zethus, the divine twins of Thebes) as well as elsewhere in Indo-European cultures more broadly (e.g., the Vedic Ashvins).

The Dioscuri were almost always associated with horses and horseback riding, much like the Ashvins, their counterparts from Indian mythology. But the brothers each had their own individual strengths, too: Castor was the dedicated horseman of the pair, while Pollux was a skilled boxer.[9]

Over time, Castor came to be seen as the more warlike twin and Pollux as the wise one.[10] In one tradition, the more militant Castor (or a version of Castor connected with Argos rather than Sparta) was said to have instructed the young Heracles in the art of war.[11]

Illustration of the horse-headed Ashvins from the Thewakamnoet (1959)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAncient sources often emphasized the athleticism of the Dioscuri, though specific references to their appearance are rare.[12] The twins were typically described, rather generically, as handsome, strong, and youthful. [13]

There is one story, however, that reveals a bit more about how the Greeks imagined the Dioscuri: during the Second Messenian War (fought between the Messenians and the Spartans), the Messenians were said to have dressed up as the Dioscuri in order to sneak up on the Spartans and kill them.

The costume the Messenians used to deceive the Spartans involved a white chiton (tunic), a red chlamys (short cloak), and a pilos (skullcap). They also carried spears and rode beautiful horses. This costume was apparently good enough to convince many of the Spartans that the enemy soldiers really were the Dioscuri.[14]

As accomplished equestrians, the Dioscuri naturally possessed remarkable horses. In some sources, these horses were even imagined as winged (or, alternatively, it was the Dioscuri themselves who had wings).[15]

The Dioscuri’s horses were named either Phlogeus and Harpagus[16] or Xanthus and Cyllarus. Sources disagree, however, on which horse belonged to which brother.[17] According to Hyginus, it was the sea god Neptune (Poseidon to the Greeks) who presented the twins with their horses as a reward for their brotherly love.[18]

The Dioscuri were often identified with the constellation Gemini, whose name comes from the Latin word for “twins.” It was said that the brothers were placed in the heavens as a reward for their virtue.[19] But the constellation Gemini was sometimes associated with other pairs from Greek mythology, too, including Amphion and Zethus, Heracles and Apollo, Heracles and Theseus, Triptolemus and Iasion, the Great Gods of Samothrace, and Phaon and Satyrus.[20]

Iconography

In ancient art, the oldest and most important attribute of the Dioscuri was the horse; the twins were often shown riding horses. They were also typically depicted wearing a type of skullcap called a pilos and carrying a spear or sword. Their iconography tended to incorporate stars, which sometimes decorated their caps.

Votive relief of the Dioscuri from Sparta (ca. 575–550 BCE)

Archaeological Museum of Sparta / George E. KoronaiosCC BY-SA 4.0The Dioscuri’s identity as twins was highlighted and symbolized in art in different ways. Often the brothers were shown facing each other. Their duality was also symbolized by pairs of objects, including amphorae, shields, snakes, and dokana (two upright wooden beams connected by two cross-beams).

In Greece and Italy, the Dioscuri were portrayed in a variety of mythical scenes. The famous Amyclae Throne, created in the latter half of the sixth century BCE, showed them rescuing their sister Helen from Theseus.[21] A painting by the celebrated artist Polygnotes, displayed in the Athenian Agora, depicted their abduction of the Leucippides.[22]

They also appeared in many representations of heroic exploits, such as the voyage of the Argonauts (on the Sicyonian Treasury) and the Calydonian Boar Hunt (on the François Vase).

Detail from the François Vase (ca. 570 BCE) showing the Calydonian Boar Hunt; Antaeus lies dying on the ground (bottom center) while Castor and Pollux attack the boar from behind (right)

National Archaeological Museum, Florence / SailkoCC BY 3.0In Rome, where the Dioscuri were known as the Castores, the iconography of the twins was largely unchanged from its Greek form. The Roman Castor and Pollux retained their youthful, athletic appearance, and their association with horses was, if anything, even more strongly emphasized.[23]

Etymology

The meaning of the title “Dioscuri” (Greek Διόσκυροι, translit. Dióskyroi; Greek dual Διοσκόρω, translit. Dioskórō) is unequivocal: it simply means “sons of Zeus.” However, the individual names “Castor” (Greek Κάστωρ, translit. Kástōr) and “Pollux” (properly “Polydeuces”; Greek Πολυδεύκης, translit. Polydeúkēs) are more obscure.

The name “Castor” seems to be related to the Greek word kastōr, meaning “beaver.” A very old suggestion claims that the name of the hero was transferred to the beaver because both were saviors of women: in myth, Castor saved his sister Helen when she was kidnapped by Theseus, while the castoreum derived from beavers was said to have medicinal properties for women.[24]

Modern scholars, however, have been hesitant to accept this reasoning. As a result, the exact origins of Castor’s name remain uncertain.[25]

The name “Polydeuces” also seems to be related to a Greek word for an animal—specifically, a “foal” or “filly” (Greek πῶλος, translit. pôlos). The second part of the name, the stem deuk-, is trickier etymologically: it may mean “to care for” but could also be related to the Indo-European *dewk-, meaning “to lead” (compare to the Latin ducere). Polydeuces’ name can thus mean either “he who cares for foals” or “leader of foals.”[26]

Statues of the Dioscuri stand tall at Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Diana RingoCC BY-SA 3.0Pronunciation

Castor

English

Greek

Castor Κάστωρ Phonetic

IPA

[KAS-ter, KAH-ster] /ˈkɑːstə(r)/

Polydeuces

English

Greek

Polydeuces Πολυδεύκης Phonetic

IPA

[pol-i-DOO-seez, -DYOO-] /ˌpɒl ɪˈdu siz, -ˈdyu-/

Titles and Epithets

The Greeks most often referred to Castor and Pollux (Polydeuces) as the Dioscuri, meaning “sons of Zeus.” But the title “Tyndarids” (Τυνδαρίδαι/Tyndarídai), “sons of Tyndareus,” also appears in both Greek and Roman literature. This is a reference to the Spartan king Tyndareus, who was sometimes named as the father of one or both of the brothers.

In their capacity as gods, the Dioscuri were often invoked under the title Ἄνακ(τ)ες (Ának(t)es), meaning “masters” or “lords.” One of their most important epithets as deities was σωτῆρες (sōtêres), “saviors,” reflecting their role as helper gods.

In Rome, the main collective title for Castor and Pollux was Castores, “the Castors.” They were also sometimes known as the Gemini, “Twins,” connecting them with the constellation of the same name.

Family

Castor and Pollux were twin brothers. However, in what became the standard version of their myth (in both Greece and Rome), they did not have the same father: Castor was the son of Tyndareus, the mortal king of Sparta, while Pollux was the son of Zeus (Jupiter), the king of the gods.

Leda, the wife of Tyndareus, had slept with both her husband and Zeus on the same night; this is what led to her sons’ double paternity. (A similar double paternity occurred with the hero Heracles and his twin brother Iphicles.)[27]

Obverse of an Attic red-figure Nolan neck-amphora (ca. 460–450 BCE) showing Zeus wielding the thunderbolt

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBut there were other versions of the Dioscuri’s parentage, too. In Homer’s epics, they are both the sons of Tyndareus,[28] while other authors made them both the sons of Zeus.[29] There may have even been a tradition in which the Dioscuri’s mother was not Leda but rather Nemesis, the goddess of retribution (though this variant would have been very obscure).[30]

As children of Leda and Tyndareus (or Zeus), Castor and Pollux were the brothers of the beautiful Helen—best known for inspiring the Trojan War—and Clytemnestra—who violently murdered her husband Agamemnon when he came home from the Trojan War. According to the Catalogue of Women, they also had two lesser-known sisters named Timandra and Phylonoe.[31] Other authors added another minor sister named Phoebe.[32]

Castor and Pollux married the Leucippides, Hilaeira and Phoebe. According to the mythographer Apollodorus, Hilaeira bore Castor a son named Anogon, while Phoebe bore Pollux a son named Mnesileus.[33] In an alternative tradition, Anogon’s name was Anaxis, while Mnesileus’ name was Mnasinus or Mnesinus.[34]

Mythology

Origins

Scholars have concluded that the Dioscuri were deities of Indo-European extraction. They are most often compared to the Indian Ashvins, youthful divine twins from the Vedas who are closely associated with horses, just like the Greek Dioscuri.

Similar pairs of divine twins were also known within the Greek world. In Thebes, the prototypical divine twins were Amphion and Zethus, who, just like Castor and Pollux, were born from the union of Zeus and a mortal woman of royal descent. Castor and Pollux appear to have originated as a local form of these divine twins in the Greek city-state of Sparta.

Fresco showing Amphion and Zethus punishing Dirce as their mother Antiope watches, from the House of the Grand Duke in Pompeii (first century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainGiven the local origins of Castor and Pollux, it is likely that the gods known as the “Dioscuri” were originally separate from them. There is evidence that the Dioscuri were deities who reached Greece through the region of Ionia (on the coast of modern-day Turkey), where they seem to have had connections with the astral realm. They were also closely connected with, or identified with, the Cabiri, the mystery gods of Samothrace.[35]

In Messenia, where the Dioscuri were claimed as local gods (supposedly born on the coastal island of Pephnos), the divine pair may have even been identified not with Castor and Pollux but with Idas and Lynceus, the mythical rivals of Castor and Pollux.[36]

Even if the Dioscuri were once distinct from Castor and Pollux, the divine twins of Sparta became universally identified with the Dioscuri at an early stage of Greek history. The cult of Castor and Pollux eventually became a Panhellenic cult, diffused throughout the Greek and Roman worlds (and beyond).

Birth

In the most common version of the myth, the Dioscuri were born when their mother Leda, the queen of Sparta, slept with her husband Tyndareus and the god Zeus on the same night. (Zeus had fallen in love with Leda and forced himself upon her in the form of a swan.)

Leda became pregnant by both of her lovers and gave birth to quadruplets: Castor and Clytemnestra, whose father was Tyndareus, and Pollux and Helen, whose father was Zeus.[37]

Leda and the Swan by Cesare de Sesto after Leonardo da Vinci (ca. 1505–1510). Wilton House, Salisbury, UK.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainSome traditions made the story even more colorful by adding that Leda laid an egg after her encounter with swan-Zeus, and that it was from this egg that her children hatched (though sources disagree as to whether all of her children who were born this way or only the “divine” ones, Pollux and Helen).[38] Pausanias claimed that the egg laid by Leda could be seen on display in a temple in Sparta.[39]

Adventures

Like all great heroes, the Dioscuri were adventurers who took part in notable heroic expeditions. Their most famous exploits included their rescue of their sister Helen from Theseus, their abduction of the Leucippides, and their fateful rivalry with the Messenian heroes Idas and Lynceus.

The Rescue of Helen

When Castor and Pollux’s sister Helen was still an unmarried girl, she was carried away by Theseus, the king of Athens. Theseus hoped to make Helen his wife as soon as she came of age. But Castor and Pollux invaded Athens and brought Helen home to Sparta.

According to the standard tradition, Theseus left Athens soon after abducting Helen to help his friend Pirithous on a reckless mission to abduct another daughter of Zeus: the Underworld goddess Persephone. The Dioscuri took advantage of Theseus’ absence to invade his kingdom.

Upon discovering that Helen was being kept at the fortress of Aphidnae, not far from Athens, the Dioscuri retrieved their sister and destroyed the fortress.[40] In the process, they captured Theseus’ mother Aethra and forced her to become Helen’s slave. In some accounts, they even installed Menestheus as the new king of Athens.[41]

Castor and Pollux Rescuing Helen by Sébastien-Louis-Guillaume Norblin de la Gourdaine (1818)

National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., United States)Public DomainPlutarch reported several variations on this myth in his Life of Theseus. Some accounts said that it was Idas and Lynceus, the enemies of the Dioscuri, who abducted Helen, giving her to Theseus for safekeeping; others, that Tyndareus himself gave Helen to Theseus to protect her from the advances of his nephews; and one tradition even involved a Trojan invasion of Greece, wherein the Trojan hero Hector (rather than the Dioscuri) captured Theseus’ mother Aethra.[42]

The Voyage of the Argonauts

The Dioscuri were among the heroes who sailed with Jason to steal the Golden Fleece from Aeetes, the ruthless king of Colchis. To accomplish this dangerous mission, Jason enlisted the help of some of the greatest heroes of his generation, who would afterwards be known as the “Argonauts” (named for the ship they sailed on, the Argo).

During the voyage, Pollux distinguished himself by defeating Amycus, the king of the Bebryces, in a boxing match. Amycus was a brute who forced all newcomers to fight him. Trying to implement this policy with the Argonauts, however, proved to be a mistake: as an accomplished boxer, Pollux easily beat Amycus in the ring. In most traditions, Pollux killed Amycus,[43] though there were some traditions in which he let him live.[44]

Detail from the frieze on the Ficoroni Cista showing Pollux (Polydeuces) defeating and binding Amycus (350–330 BC)

National Etruscan Museum, Rome / SailkoCC BY-SA 4.0The bout between Pollux and Amycus was the Dioscuri’s main contribution to the voyage of the Argonauts. In ancient art, however, Castor and Pollux were sometimes shown helping the witch Medea fight the bronze automaton Talos, who attacked the Argonauts as they were returning home.[45]

The Calydonian Boar Hunt

According to some sources, the Dioscuri were also among the heroes who participated in the Calydonian Boar Hunt.[46] This famous exploit took place after the goddess Artemis sent a monstrous boar to ravage Calydon, the kingdom of Oeneus—a punishment for Oeneus’ failure to properly honor Artemis.

In addition to the Dioscuri, many of the greatest heroes of Greek mythology also took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt, including Theseus, Peleus (the father of Achilles), the heroine Atalanta, and Oeneus’ son Meleager, among others.

Meleager Killing the Calydonian Boar by Theodoor Boeyermans (1677)

Musée de la chasse et de la nature, ParisPublic DomainOther Adventures

The Dioscuri took part in a handful of lesser adventures, too, most of them involving other heroes from the generation of the Argonauts. For example, they competed in the funeral games of Pelias, Jason’s uncle, who died shortly after the Argonauts’ return.[47] They also successfully competed in the first Olympic Games, held by Heracles.[48]

In another myth, the Dioscuri (together with Jason) helped Peleus sack the city of Iolcus. Acastus, the king of Iolcus, had tried to have Peleus killed, but Peleus was able to escape. He took his revenge by destroying Iolcus and killing his would-be assassin.[49]

Some of the twins’ adventures were associated with the eastern Aegean region, providing further evidence that the deities known as the Dioscuri may have reached Greece from the East (see above). For example, the Dioscuri were credited with founding the city of Dioscurias in the Black Sea region of Pontus (near Colchis).[50]

They were also said to have been initiated into the mysteries of Samothrace (where they were closely connected with the local gods known as the Cabiri).[51] Like many heroes, the Dioscuri were initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, too.[52]

Metope of the Dioscuri returning from a cattle raid, from the Sicyonian Treasury at Delphi (ca. 560 BCE)

Archaeological Museum, Delphi / ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0Other myths restored the Dioscuri to their homeland of Sparta in the southern Peloponnese. In the Catalogue of Women, for example, it is the Dioscuri who supervise the courting and marriage of their sister Helen (effectively helping to choose the next king of Sparta).[53]

An early tradition also had the Dioscuri fight Hippocoon and his sons, who had exiled Tyndareus (Castor’s father) from Sparta. In the standard version, Hippocoon and his sons were ultimately killed by Heracles, who wished to settle a private vendetta.[54] But in an alternative version, it was the Dioscuri who fought the sons of Hippocoon, apparently due to a romantic rivalry (the source is fragmentary, so the details are unclear).[55]

Death and Deification

The deaths of the Dioscuri were the result of a quarrel with the twins Idas and Lynceus, the sons of Tyndareus’ brother (and their uncle) Aphareus. There are different explanations for this altercation.

In one tradition, the two sets of twins fell out over a cattle raid that they had carried out together. While dividing their spoils, Idas and Lynceus tricked Castor and Pollux into giving up their share of the cattle.

Furious at being tricked, the Dioscuri plotted to ambush Idas and Lynceus on their way home. But the sharp-eyed Lynceus spotted Castor hiding inside a hollow tree. In the struggle that followed, all but Pollux lost their lives.[56]

In another tradition, Idas and Lynceus attacked the Dioscuri for stealing their brides, Phoebe and Hilaeira (also known as the “Leucippides,” the daughters of Leucippus). The two sets of twins fought in a pitched battle near the grave of Aphareus (Idas and Lynceus’ father).[57]

The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus by Peter Paul Rubens (c. 1618), Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainSome sources seemingly tried to reconcile these various traditions, having Idas and Lynceus mock the Dioscuri for marrying the Leucippides without paying a bride price. In response, the Dioscuri promptly stole Idas and Lynceus’ cattle, with the intention of giving them to Leucippus as a belated bride price. Angry about the theft of their cattle, Idas and Lynceus attacked the Dioscuri.[58]

Whatever the reason for their conflict, the battle between the Dioscuri and Idas and Lynceus was usually described in the same way: Lynceus killed Castor, while Pollux killed Lynceus. Just as Idas was attacking Pollux, Zeus struck him down with a thunderbolt (or, alternatively, Pollux simply turned around and killed Idas, too).[59]

Zeus wished to make his son Pollux immortal, but Pollux would not accept this while his brother Castor was dead. In the best-known version of the myth, a unique compromise was reached, wherein they enjoyed immortality on alternating days:

These two the earth, the giver of life, covers, albeit alive, and even in the world below they have honor from Zeus. One day they live in turn, and one day they are dead; and they have won honor like unto that of the gods.[60]

It is unclear, however, if they both alternated their days between the Underworld and the upper world, or if one brother was in the Underworld while the other was among the gods.

The Dioscuri Appear in the Sky on White Horses and Offer a Sword and Helmet to the Prince by Pietro da Cortona (17th century)

Palazzo Pitti, Florence / IlSistemoneCC BY-SA 4.0Castor and Pollux in Rome

The Dioscuri entered Roman religion quite dramatically at the Battle of Lake Regillus (ca. 496 BCE). This battle was fought between a coalition of Latin states, led by the banished Roman king Tarquinius Superbus, and the fledgling Roman Republic. During the battle, the dictator Aulus Postumius, commander of the Roman army, promised Castor a temple in Rome if he came to his aid.

Castor must have been intrigued by the prospect of having the Romans worship him: it was said that during a critical moment of the battle, two handsome and tall horsemen were seen riding white horses and wearing purple robes.

After the Romans had won the battle, the two horsemen were seen again in the Roman Forum, where they drank from the fountain of Juturna, announced the victory, and vanished. These horsemen were later identified as Castor and Pollux.[61]

Battle of Lake Regillus by Tommaso Laureti (between 1587 and 1594)

Capitoline Museums, RomePublic DomainA few years later, in 484 BCE, the Romans dedicated a temple to the Dioscuri in the Forum.[62] Since the Romans thought of the horseman Castor as the dominant twin, they referred to the temple as the Temple of Castor, and to the twins collectively as the Castores, meaning “the Castors.”

The Romans often boasted that Castor and Pollux continued to stand by them throughout history. According to legend, the twins came to Rome in 168 BCE to announce Aemilius Paulus’ victory over the Macedonians in the Battle of Pydna. It was said that when they first appeared, the doors of their temple opened of their own accord, and that when they arrived at the Forum, they bathed their horses in the fountain of Juturna.[63]

Likewise, Castor and Pollux were no doubt the godlike, ivy-crowned twins who supposedly announced the Romans’ victory over the Cimbri (101 BCE).[64] Castor and Pollux were also said to have been present at the Battle of Pharsalus (48 BCE), in which Julius Caesar defeated his rival Pompey.[65] Finally, when Drusus died on the Rhine (9 BCE), Castor and Pollux were seen riding in the Roman camp.[66]

Worship

Greece

Temples and Sanctuaries

Within the Greek world, the cult of the Dioscuri was particularly prevalent in the Peloponnese. Sparta, Therapne, and Argos all claimed to have the tomb of one or both of the Dioscuri, who were believed to live underground.[73] The Spartans preserved an ancient house that was thought to have belonged to the Dioscuri.[74] And in several Peloponnesian cities, including Sparta and Argos, there were families who boasted descent from the divine twins.

The Dioscuri had temples and sanctuary complexes, too, including at the Menelaion in Therapne, just outside of Sparta;[75] at Sparta itself;[76] and at Argos.[77] In Sparta, where worship of the Dioscuri was best established, there was a statue of Castor and Pollux at the entrance to the race course. Likewise, on the Messenian island of Pephnos, there were bronze statuettes of the Dioscuri exposed to the open air and the sea.[78]

Votive relief showing the Dioscuri from Sparta (1st century BCE)

Archaeological Museum, Sparta / George E. KoronaiosCC BY-SA 4.0Occasionally, Castor and Pollux were worshipped separately rather than collectively. Castor was sometimes worshipped on his own at Sparta,[79] and Pollux at Therapne.[80]

In other parts of Greece, including Attica, Cyrene, and Sicily, Castor and Pollux were sometimes honored as the Anakes. Because of this, the temple of Castor and Pollux in Athens was called the Anacaeum.

Festivals and Rituals

Festivals of the Dioscuri were usually called Dioscuria and were widely celebrated by the ancient Greeks. In Sparta, the Dioscuria involved sacrifices, rejoicing, and drinking.[81] Cyrene, a Greek colony in North Africa, was also known for hosting a great Dioscuria festival.[82]

In Attica, where the Dioscuri were worshipped as the Anakes or Anaktes, their festival was known as the Anakeia. There was also an Anakeia festival celebrated by the city of Amphissa near Delphi, though the identity of the gods being honored at this festival has been disputed since antiquity.[83]

Relief of the Dioscuri riding their horses above a winged Nike, a banquet (theoxenia) laid out for them below (2nd century BCE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5The rite of theoxenia (literally, “entertaining of the gods”) was also closely associated with the Dioscuri.[84] An elaborate feast would be prepared, and the host (whether an individual or a public group) would invite the gods to take part.

Rome

Temples and Sanctuaries

In Rome, the twins were believed to have helped the Roman army during the Battle of Lake Regillus (ca. 496 BCE); following their victory, the Romans honored their divine helpers with a temple of Castor and Pollux, built in the Roman Forum. Later, the Romans erected additional temples to the brothers.

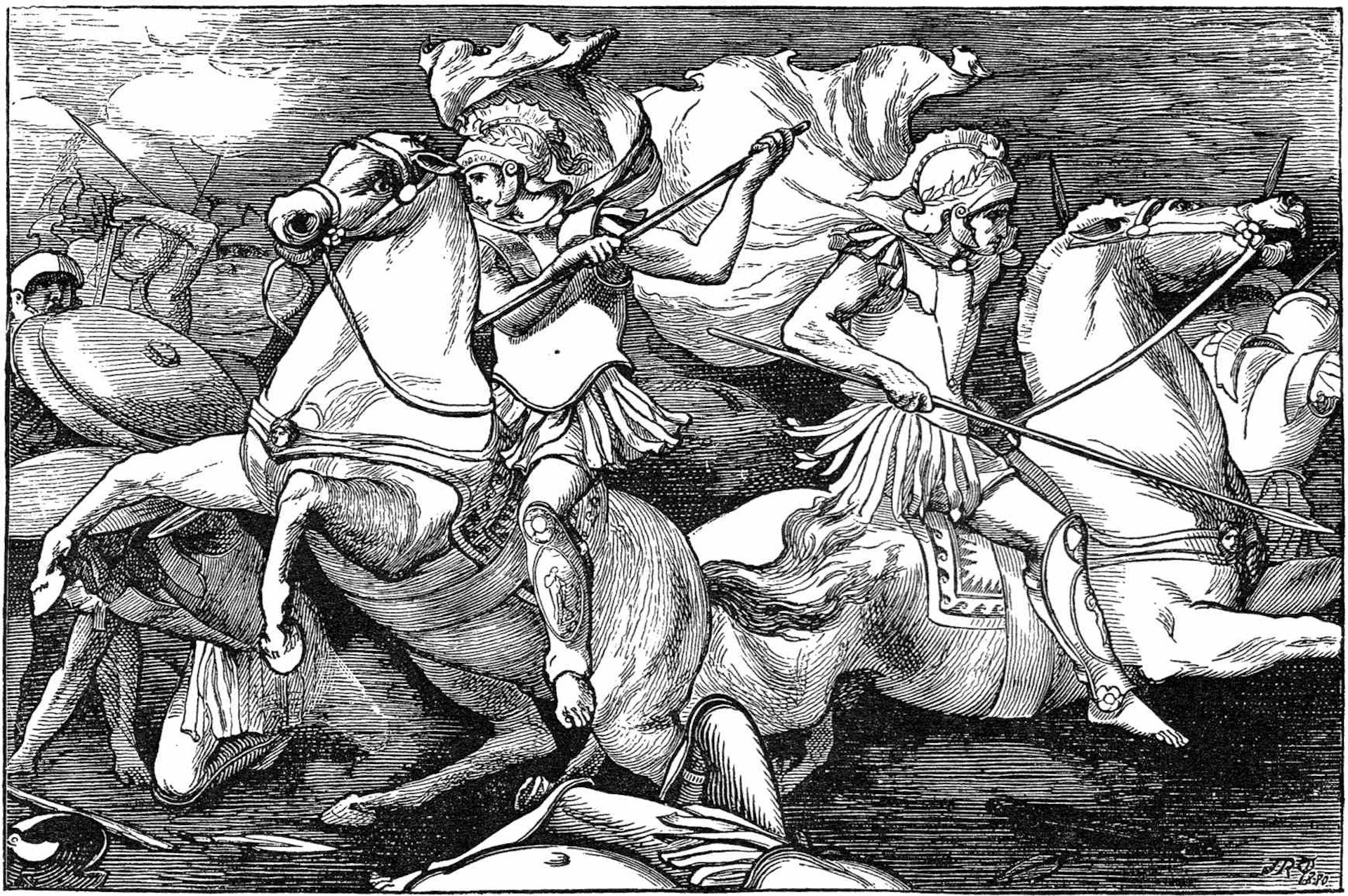

Illustration of Castor and Pollux at the Battle of Lake Regillus by John Reinhard Weguelin (1880)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe cult of the Dioscuri probably reached Rome via Italian cities such as Lavinium, Ardea, or even Tusculum, moving northwards from the Greek cities of southern Italy.[85] However, the Romans almost never referred to the twins as the Dioscuri, instead simply calling them Castor and Pollux, or, collectively, the Castores.

The Castores were firmly established in Rome by the beginning of the fifth century BCE, when legend says they helped the Roman army win the Battle of Lake Regillus (see above). The twins’ temple in the Roman Forum was dedicated in 484 BCE.[86]

In Rome, Castor was the more important of the twins from the beginning, perhaps because his mythology better embodied the key Roman attributes of horsemanship and war. This is why the Romans referred to the twins as the Castores, “the Castors,” and why their temple was known from the beginning as the aedes Castoris, the “temple of Castor.”[87]

Festivals and Rituals

The Romans commemorated the day on which the Temple of Castor was dedicated—the Ides of Quinctilis (July 15)—with an annual feast in honor of Castor and Pollux. This celebration featured a parade of Roman youths of the equestrian class. During the parade (known as the Transvectio equitum), young men on horseback went from the Temple of Mars on the Via Appia to the Temple of Castor and finally to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill.[88]

Roman Ruins Landscape by Paul Bril (1600)

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, DresdenPublic DomainOther festivals and rituals of Castor and Pollux in Rome highlighted their connection with water and water deities. In Rome and Ostia, the twins were celebrated together with the sea god Neptune during the feast of the Neptunalia on July 23.

Other Cults

Though the cult of the Dioscuri (or Castores) was best known in Greece and Rome, the twins were also worshipped in other parts of the Mediterranean world.

In Etruria, for example, Castor and Pollux are attested from a relatively early period, appearing in colorful vase paintings. The Etruscans knew the twins as the Tinas Cliniar, or, individually, as Castur (Castor) and Pultuce (Pollux); they were the sons of Tinia (Zeus/Jupiter) and Latva (Leda), and the brothers of Elinai (Helen) and Clutmsta (Clytemnestra).

Votive statue of Jupiter Dolichenus (2nd or 3rd century CE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 4.0In Syria, Castor and Pollux were honored as the sons of Jupiter Dolichenus, a hybrid deity who became important during the Roman Empire. Early historians also claimed that the Celts living near the ocean worshipped Castor and Pollux—probably a reference to Celtic divine twins such as Divanno and Dinomogetimarus.[89] The Germanic divine twins known as the Alci or Alces were also identified with Castor and Pollux in antiquity.[90]

Popular Culture

Castor and Pollux are rarely encountered in modern pop culture, though they do play a minor role in some adaptations of the voyage of the Argonauts, such as the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts and the 2000 television miniseries of the same name.

Despite this cultural absence, the names Castor and Pollux are sometimes used to describe other twins. For example, there are at least four sets of twin summits named after Castor and Pollux: in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming; in the Pennine Alps at the Swiss-Italian border; in Glacier National Park in western Canada; and in Mount Aspiring National Park in New Zealand.

Fictional twin characters named Castor and Pollux appear in novels by Robert A. Heinlein (The Rolling Stones), Suzanne Collins (The Hunger Games trilogy), and Rick Riordan (Percy Jackson and the Olympians series). The villains of the 1997 film Face/Off are likewise named Castor and Pollux, while the role-playing video game Persona 3 features characters named Castor and Polydeuces.

Finally, Canadian singer Kathryn Calder released a song in 2010 titled “Castor and Pollux.