Atlas

Overview

The son of Iapetus and Clymene, Atlas was a Titan famed for his prodigious strength and intelligence. Having been defeated by the Olympians in the Titanomachy, Atlas was condemned to bear the weight of the celestial sphere for all eternity. He was a popular figure in Greek mythology, and appeared in the stories of heroes such as Heracles and Perseus. Closely associated with the earth and other heavenly bodies, Atlas was also a master of astronomy, geography, and navigation.

Etymology

The name “Atlas” was likely the result of joining the prefix a- with the ancient Greek word tlēnai, meaning “to bear.” The latter may have been used in reference to Atlas’ reputation as the bearer of the celestial sphere. Some modern scholars, however, insist that Atlas’ name is pre-Greek in origin.[1]

An alternative etymology suggests a North African origin for Atlas’ name, tying it to the Atlas Mountains in northwestern Africa. According to this theory, the Greek name “Atlas” was derived from adrar, the Berber word for the mountains that came to represent the doomed Titan (see below).

Atlas Mountains range, as seen in Morocco.

ErWinCC BY-ND 2.0Pronunciation

English

Greek

Atlas Ἄτλας Phonetic

IPA

[AT-luhs] /ˈætləs/

Epithets

Atlas was often given the epithet Telamōn (“enduring”), due to his toils as the bearer of heaven.[2]

Attributes

A figure of prodigious strength, Atlas famously bore the world on his shoulders and was renowned for his wit and wisdom. According to a number of ancient sources, such as Diodorus of Sicily’s Library of History, Atlas was a master philosopher, mathematician, astrologer and astronomer. Some sources have even described Atlas as the inventor of astronomy: “For Atlas had worked out the science of astrology to a degree surpassing others and had ingeniously discovered the spherical nature of the stars.”[3]

Family

Atlas had a large family with connections across Greek mythology. According to the best-known tradition, he was the son of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Clymene,[4] though there was another version in which his mother was Asia (also an Oceanid).[5] Atlas had several brothers, including Prometheus, Epimetheus and Menoetius. Some sources named three additional brothers: Anchiale,[6] Buphagus,[7] and Dryas.[8]

Atlas had a number of lovers, including Hesperis, Pleione, and the Oceanid Aethra. With Hesperis,[9] Atlas sired the mysterious Hesperides, sometimes known as the Atlantides.[10] With either Pleione[11] or Aethra,[12] he had seven daughters known collectively as the Pleiades (Maia, Electra, Taygete, Alcyone, Celaeno, Sterope and Merope).[13] They achieved fame as the companions of Artemis and later transformed into stars to elude the amorous pursuits of the hunter Orion.

Atlas's other daughters included Calypso,[14] an enchantress famed for her seven-year affair with Odysseus; Dione;[15] Maera;[16] and the Hyades, a group of nymphs known as rain-makers.[17] Finally, Atlas had a son named Hyas, an archer and hunter.[18]

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mothers

- Clymene

- Asia

Siblings

Brothers

Sister

- Prometheus

- Epimetheus

- Menoetius

- Buphagus

- Dryas

- Anchiale

Consorts

Lovers

- Aethra

- Hesperis

- Pleione

Children

Daughters

Son

- Calypso

- Dione

- Hesperides

- Hyades

- Maera

- Pleiades

- Hyas

Mythology

Origins

Little is known about Atlas’ origins, though Hesiod offers some insight into his role in Greek mythology. According to the Theogony, Atlas fought alongside his kin in the Titanomachy, when the Olympians rose up against the Titans. Ultimately, the Titans fell to the usurpers’ superior strength, and Zeus meted out punishments to all who had opposed him. Atlas was tasked with supporting the “celestial sphere”—that is, the heavens or the sky:

And Atlas through hard constraint upholds the wide heaven with unwearying head and arms, standing at the borders of the earth before the clear-voiced Hesperides; for this lot wise Zeus assigned to him.[19]

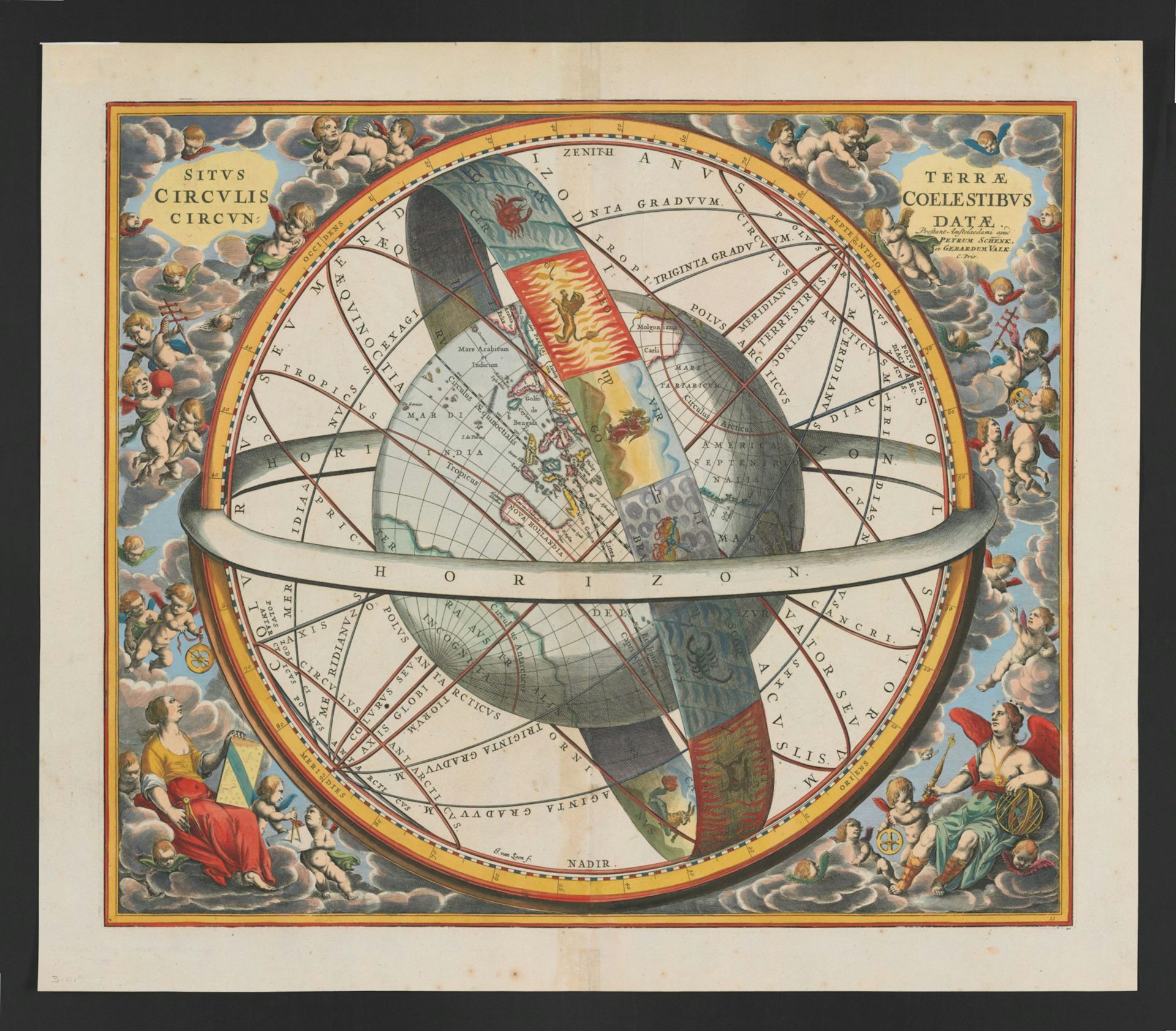

The earth-centric sphere of the universe, imagined here in The Celestial Atlas of Andreas Cellarius in 1660, describes the view as "Ptolemaic," or according to the Greek astronomer and scientist Ptolemy, who lived in Roman Egypt in the 1st century CE.

Stanford University LibrariesPublic DomainAtlas and the Heroes

Heracles

While Atlas had no myths to call his own, he did make several appearances in the tales of Greek heroes. During Heracles’ Twelve Labors, for example, Atlas aided Heracles in retrieving a set of golden apples. The apples, which were kept in Hera’s garden, were tended by the Hesperides, Atlas’ daughters (hence their name, the “Apples of the Hesperides”). Atlas agreed to fetch the apples, asking only that Heracles hoist the celestial sphere while he was away.

When an unburdened Atlas finally returned with the apples, he saw an opportunity to be free of his curse forever. He tried to trick Heracles, offering to deliver the apples for him, with the intention of leaving Heracles to bear his eternal burden. Heracles saw through the ruse, however, and asked Atlas to hold the celestial sphere for just a moment while he rearranged his cloak. When Atlas agreed, Heracles stole away with the golden apples, leaving the Titan to bear the weight of the heavens once more.[20]

Hercules Relieving Atlas of the Globe, c. 1530, by German artist Lucas Cranach the Elder.

National Gallery of Art, WashingtonPublic DomainIn another version, however, Heracles built the Pillars of Heracles to hold up the sky on Atlas' behalf.[21] He thus freed Atlas of his punishment, just as he freed Atlas’ brother Prometheus from the eagle sent every day to eat his liver. There were also other traditions in which Atlas was eventually released from his punishment without Heracles’ help.[22]

Perseus

Atlas also appeared in a tale of Perseus, the legendary hero of early Greek lore. According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Perseus traveled to Atlas’s kingdom in northwestern Africa and demanded shelter, claiming that he was the son of the great Zeus. Atlas refused, as he had received a prophecy foretelling the downfall of his kingdom at the hands of one of Zeus’s offspring. In his rage, Perseus used Medusa’s head to transform Atlas into a stony mountain range—the Atlas mountains. Ovid described this scene in vivid detail:

Although he dared not rival Atlas' might, Perseus made this reply; “For that my love you hold in light esteem, let this be yours.” He said no more, but turning his own face, he showed upon his left Medusa's head, abhorrent features.—Atlas, huge and vast, becomes a mountain—His great beard and hair are forests, and his shoulders and his hands mountainous ridges, and his head the top of a high peak;—his bones are changed to rocks. Augmented on all sides, enormous height attains his growth; for so ordained it, ye, O mighty Gods! who now the heavens' expanse unnumbered stars, on him command to rest.[23]

Other Interpretations

Certain “rationalizations” of the myth of Atlas circulated in the ancient world. According to some authors, Atlas was a wise king who ruled in North Africa. Because of his expansive knowledge of astronomy, he was said to figuratively hold the heavens on his shoulders.[24]

Pop Culture

Atlas has remained a prominent figure in modern popular culture. The name of the Atlantic Ocean can be traced to Atlas, albeit indirectly; the ancients called this body of water the “Ocean of Atlas,” from which the current name is derived. The same is true of the Atlas Mountains, which Ovid believed to be the physical form of the petrified Titan.

The term “atlas” is also used to refer to a book of maps. This usage originated in the sixteenth century, when Gerardus Mercator—father of the Mercator projection—dedicated his map of the world to the ancient Titan once tasked with holding up the heavens.

The iconic image of Atlas bearing the world on his shoulders has been depicted in countless statues; one of the most famous examples stands in front of Rockefeller Center in New York City. Depictions of the Titan have also appeared throughout European architecture, where they are typically used in place of (or at the top of) a column, making it appear as though Atlas is supporting the structures above.

This well-known Art Deco statue of Atlas holding the world sits outside the Rockefeller Center in New York, a center and symbol of capitalism. It was sculpted in 1937 by Lee Lawrie and Rene Paul Chambellan.

PortableNYCToursCC BY-SA 4.0Atlas appears in the title of Ayn Rand’s dystopian novel Atlas Shrugged (1957). Finally, he is one of the major villains in the video games God of War 2 and God of War: Chains of Olympus.