Hestia

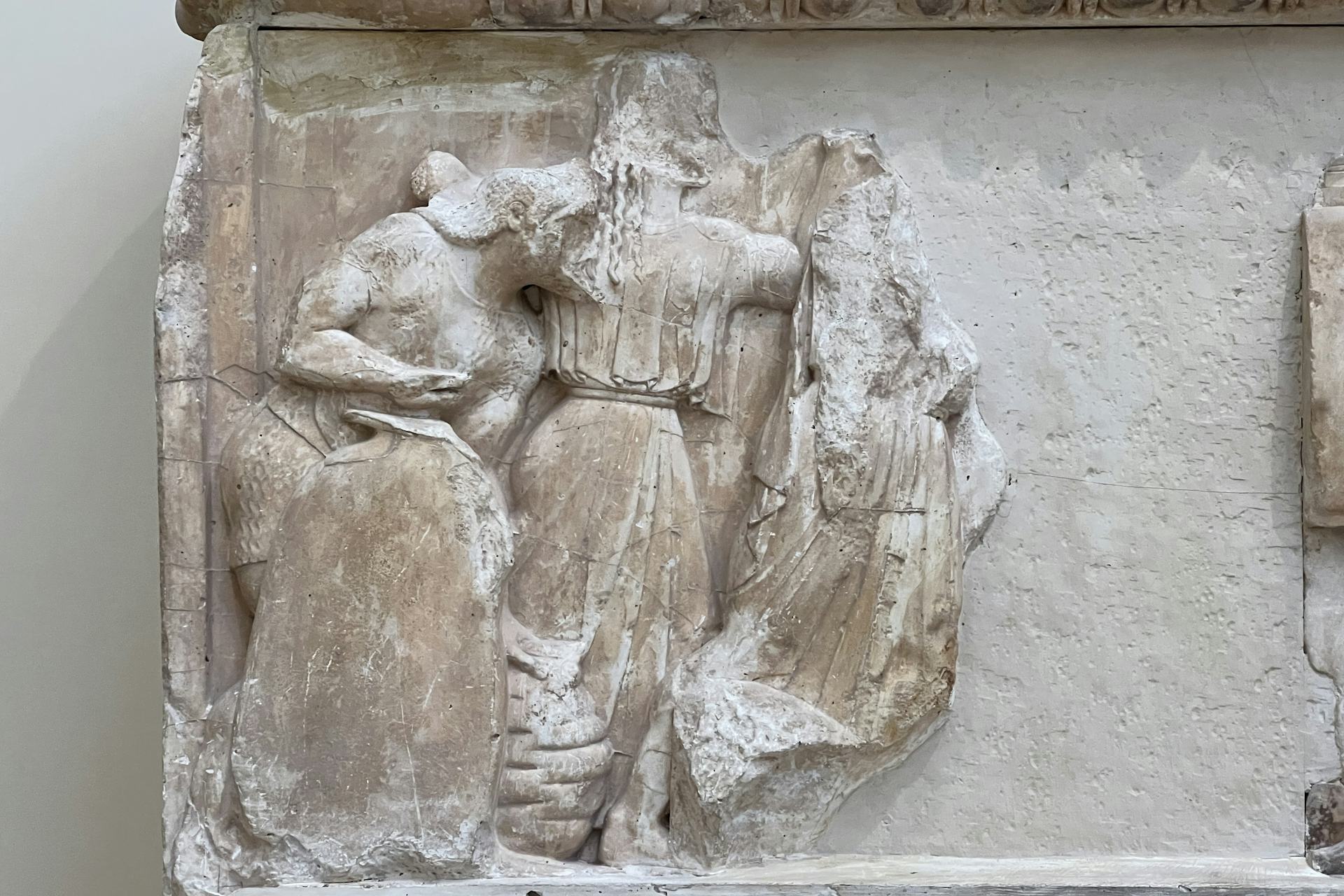

Possible representation of Hestia on the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi (6th century BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, Delphi / Chabe01CC BY-SA 4.0Overview

Hestia was the Greek goddess of the hearth and home and ruler of the domestic sphere. She was a child of the Titans Cronus and Rhea and thus the sister of Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, and Hades. Like her siblings, she was sometimes worshipped as one of the Twelve Olympians.

Hestia was symbolized by the hearth, which burned in every Greek home as well as in many public buildings. A dutiful and inconspicuous deity, she embodied the Greek ideal of feminine modesty.

Key Facts

What were Hestia’s attributes?

Hestia’s principal attribute was the hearth with which she was so intimately associated. The goddess herself was typically represented wearing a veil and robe. In some images, she held a flowering branch or kettle as well.

Possible representation of Hestia on the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi (6th century BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, Delphi / Chabe01CC BY-SA 4.0How was Hestia worshipped?

Hestia had very few temples in the ancient world. However, because she was the goddess of the hearth, every single hearth—both those in private homes and in public buildings—could be considered a sanctuary to Hestia.

The cult of Hestia was closely associated with an eternal flame that was kept forever burning at a public sanctuary. (There was also an eternal flame in Rome at the temple of Vesta, Hestia’s Roman counterpart.)

Roman Fragments with Statue of Hestia by Georg Christoph Eimmart II (1675 or earlier)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainHestia and Priapus

Hestia had virtually no mythology of her own. However, the Roman poet Ovid recounted one story in which the vegetation god Priapus tried to rape the virgin Hestia. Finding Hestia sleeping in the woods, Priapus approached her stealthily with the intention of having his way with her. But a donkey suddenly brayed nearby, waking the goddess.

When the other gods learned of Priapus’ intentions, they banished him from their gatherings. He was sent to live in the forest with the woodland gods, far from Mount Olympus.

Autumn in the Guise of Priapus by Pietro Bernini assisted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1616–1617)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEtymology

The Greek word hestia means “hearth” or “fireplace.” As the central meeting place within the house, as well as the location of the sacrifices made in Hestia’s honor, the hearth was an apt symbol for the domestic goddess.

The etymology of the word hestia remains somewhat obscure. Some have traced it to the Proto-Indo-European roots *wes (“burn”) and *h₂wes- (“dwell, pass the night, stay”).[1] Others have suggested connections between Hestia’s name and other words for “hearth,” including eschara in Greek and jestěja in Slavic, but these derivations are not generally accepted today.[2] According to Robert S. P. Beekes, the etymology of Hestia is most likely pre-Greek.[3]

It should be noted that the name “Vesta,” the virginal Roman goddess who served as Hestia’s mythological counterpart, is derived from the same etymological root.

Epithets

Hestia was not showered with as many epithets as the other Olympian gods. The Homeric epics, probably the best source for poetic epithets in Greek literature, do not contain any references to the goddess Hestia (and so obviously do not give us any epithets for her). In some later sources, Hestia did have a handful of epithets, among them basileia (“queen”), chloomorphos (“verdant”), and aidios (“eternal”).

Attributes

Hestia was the goddess of the hearth and household. Revered in both the private and public spheres, she was symbolized in the hearth of each individual household but also at the community hearth located in the prytaneum, a public building found at the center of each Greek polis.

Hestia was usually represented as a modestly veiled woman wearing a long robe. In art, she was sometimes shown holding a flowering branch or a kettle. Her chief attribute was the hearth or hearth fire for which she was named. In fact, she often appeared in these forms rather than as a human.

5th century BCE kylix representing Hestia holding a flowering branch.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFamily

Hestia was the firstborn child of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, rulers of the cosmos before the Olympians; her siblings included Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus.[4]

Hestia was not only the eldest child but also the first to be swallowed by the tyrannical Cronus, who was convinced that his children would overthrow him. When Zeus forced his father to regurgitate his brothers and sisters, Hestia was the last to emerge, making her both the first to be born and the last to be reborn.

As a virgin goddess, Hestia had no children.

Family Tree

Mythology

Details about Hestia are scarce, making her personality, chief attributes, and mythology difficult to determine. The Homeric Hymns, religious poems written in honor of the Greek gods between the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, give us only a fleeting impression of the goddess.

The twenty-fourth Hymn, for example, addresses Hestia as “you who tend the holy house of the lord Apollo, the Far-shooter at goodly Pytho, with soft oil dripping ever from your locks.”[5] In the twenty-ninth Hymn, Hestia is said to reside “in the high dwellings of all, both deathless gods and men who walk on earth.”[6]

A somewhat more substantial story is found in the fifth Homeric Hymn, which is dedicated to Aphrodite. Here, Hestia, a chaste virgin, is contrasted to Aphrodite, the promiscuous goddess of love and sexual pleasure. In short, Hestia becomes a kind of anti-Aphrodite. So committed was the goddess of the hearth to her virginity, in fact, that she once rejected two of the most eligible suitors in the cosmos, Poseidon and Apollo, when they came to ask for her hand in marriage:

Hestia and the Olympians

The most modest, tranquil, and industrious of the gods, Hestia rarely appeared in the ribald and raucous stories typical of Greek mythology. Instead, she dutifully observed her role in the domestic sphere.

Some scholars doubt whether Hestia even belonged to the official pantheon of the Twelve Olympians, as she and Dionysus often exchanged the honor of filling the twelfth slot. On the east frieze of the Parthenon, a huge temple of Athena on the Athenian Acropolis, Dionysus is depicted among the Olympians, while Hestia is nowhere to be found. On the other hand, the altar of the Twelve Olympians—also, incidentally, in the city of Athens—included Hestia but not Dionysus.

For some, Dionysus’ presence among the Twelve Olympians is yet another sign of Hestia’s peaceful and generous nature: she may have given up her seat to the younger Dionysus in order to prevent conflict among the gods. It should be noted, however, that no such myth existed in antiquity (as far as we can tell)—it is a modern fiction posing as an ancient one. It remains unclear how the ancients coped with the rival claims of two different gods for the title of twelfth Olympian.[9]

Hestia and the Greeks

Hestia’s domesticity tells us much about what was expected of Greek mothers as the matrons of the household. Classical Greece was a deeply patriarchal society, where only men enjoyed the benefits of public life in the polis. Women, in contrast, were deprived of these rights and privileges and instead confined to the domestic sphere. Dutiful, obedient, and inconspicuous, Hestia embodied the Greek ideals of motherhood and womanhood.

Worship

Though rarely remembered today, the cult of Hestia thrived in its time. Hestia was the first to be addressed in every prayer and received the first share of every sacrifice.[10] In the domestic sphere, her worship was centered around the hearth, itself the focal point of each home.

In the public sphere, Hestia was honored in community buildings such as the prytaneum. Every Greek city had a prytaneum, which housed the community hearth of Hestia and her cult statue. The structure was used for sacrifices to the goddess but also for various official functions, such as housing guests and ambassadors. Hestia also had a hearth in each city’s Boule, the City Council.

Whether in a private household or a public building, Hestia’s hearth guaranteed protection and was often used as asylum by suppliants.

Because every hearth was effectively a sanctuary of Hestia, there were few separate temples dedicated to her in the Greek world. One exception was the city of Hermione, which did have a temple of Hestia; however, it was unusual in that it contained no cult image or statue of her.[11] Interestingly, this was not true of Hestia’s Roman equivalent, Vesta, who had a very important temple in the heart of Rome.

Hestia was commonly associated with the “eternal flame,” a sacred fire that burned for her and was never allowed to be extinguished. Whenever a Greek city founded a colony, the settlers would bring fire from their mother city’s eternal flame to burn in their new settlement. The Romans also observed this practice in connection with their goddess Vesta.

Hestia was sometimes also celebrated and invoked with sacrifices of various foods and animals, such as young cows.

Pop Culture

Hestia has been featured in several pop culture depictions of Greek mythology. In the Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, she appears as a humble and dutiful goddess who is above the petty politics of the other deities. In the Xena and Hercules television series, her likeness appears in the Cave of Hestia, though she herself does not. In the same series, a religious group known as the Hestian Virgins appears regularly.