Penelope

Overview

Penelope was a beautiful princess from Sparta, best known for marrying the hero Odysseus. The couple lived together in Odysseus’ small island kingdom of Ithaca, where they had a son named Telemachus.

When Odysseus went to fight in the Trojan War, Penelope awaited his return for twenty years—the ten years of the war, and another ten as Odysseus was tossed about at sea trying to get home. During this time, suitors came from far and wide to seek Penelope’s hand in marriage, but she remained unwaveringly loyal to her husband (at least in the familiar tradition). Using her cunning, she managed to hold off the suitors for years. When Odysseus finally did make it back to Ithaca, he killed the suitors and was at last reunited with his beloved wife.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Penelope” (Greek Πηνελόπεια, translit. Pēnelópeia) has been disputed since antiquity.

Some have attempted to derive the name from the Greek word πήνη (pḗnē), meaning “weft” or “loom.”[1] This would make Penelope “the weaveress,” an apt moniker that reflects both the literal weaving that plays an important role in her myth (see below), as well as her more metaphorical “weaving” of cunning plots to fend off her suitors.

Others have argued that Penelope’s name came from the Greek word pēnelops, which is a kind of duck.[2] This etymology may be related to the myth that Penelope was thrown into the sea as a baby and saved by ducks.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Penelope Πηνελόπεια (translit. Pēnelópeia) Phonetic

IPA

[puh-NEL-uh-pee] /pəˈnɛl ə pi/

Alternate Names

Ancient commentators have noted that, in some sources, Penelope’s original name was Ameirace (Greek Ἀμειράκη, translit. Ameirákē), Arnacia (Greek Ἀρνακία, translit. Arnakía)[3], or Arnaea (Greek Ἀρναῖα, translit. Arnaîa).[4]

Titles and Epithets

Penelope had several epithets, especially in Homer’s Odyssey. The most important of these emphasized her virtue and cunning, including ἀμύμων (amýmōn, “blameless”), πινυτή (pinytḗ, “prudent”), περίφρων (períphrōn, “wise, sage”), and ἐχέφρων (echéphrōn, “sensible, discreet”).

Attributes and Iconography

Famous for her beauty as well as her intelligence and faithfulness, Penelope was often seen as the model wife in the ancient world.

In time, Penelope would become strongly associated with weaving and the loom, due to the memorable myth in which she delayed her unwanted suitors by promising to marry one of them only after she had finished weaving a shroud. The shroud, however, never seemed to get any closer to completion (unknown to the suitors, Penelope would unravel her work each night).

Though this is a very ancient myth, the image of Penelope at the loom was not popularized in the visual arts until much later in European history. In ancient art, Penelope was more commonly depicted mourning Odysseus’ absence, saying goodbye to her son Telamachus, or receiving gifts from the suitors.[5]

Family

Penelope’s father was Icarius.[6] Her mother was either a Naiad named Periboea,[7] Ortilochus’ daughter Dorodoche,[8] Eurypylus’ daughter Asterodia,[9] or Lygaeus’ daughter Polycasta.[10]

Penelope had multiple siblings, though their names and even their number vary across different sources. In the Odyssey, she has several brothers (though Homer never specified their names or how many there were) and a sister named Iphthime;[11] according to Strabo, she had two brothers named Alyzeus and Leucadius;[12] according to Apollodorus, she had five brothers named Thoas, Damasippus, Imeusimus, Aletes, and Perilaus, but no sisters.[13]

Other sources listed her brothers (or half-brothers) as Amasichus, Phalereus, Thoon, Pheremmelias, and Perilaus, while her sister, called Iphthime in the Odyssey, was either Hypsipyle, Mede, Laodamia, or Laodice.[14] One source claimed that she also had a brother (or half-brother) named Elatus.[15]

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mothers

- Periboea

- Polycasta

- Asterodia

- Dorodoche

Siblings

Brothers

Sisters

- Alyzeus

- Leucadius

- Aletes

- Damasippus

- Imeusimus

- Perilaus

- Amasicus

- Thoas

- Phalereus

- Pheremmelias

- Thoon

- Elatus

- Hypsipyle

- Ipthimide

- Mede

- Laodamia

- Laodice

Consorts

Husbands

Lovers

- Odysseus

- Telegonus

Children

Sons

- Telemachus

- Pan

- Italus

- Arcesilaus

- Poliporthes

- Ptoliporthes

Mythology

Origins

There are only scattered references to Penelope’s early life. In one tradition, known only from commentators writing in late antiquity, the infant Penelope was thrown into the sea by either her own parents or by Nauplius, a neighboring king. She was saved, however, by ducks, which in Greek are called pēnelopes. Because of this, she was renamed Penelope.[23]

Marriage to Odysseus

When Penelope was of marriageable age, many suitors came to seek her hand. Her father Icarius challenged the men to a footrace and promised his daughter to the winner, who turned out to be Odysseus.[24] In other traditions, however, Odysseus was awarded Penelope as a bride after he helped her uncle Tyndareus safely arrange the marriage of his own daughter, Helen, to Menelaus.[25]

Illustration of a plate by Jean-Auguste Barre showing Odysseus and his dog Argus.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAfter the wedding, Odysseus brought Penelope to his modest island kingdom of Ithaca. Soon they had a son named Telemachus. But their happiness was short-lived. Back in Sparta, Penelope’s cousin Helen had left her husband Menelaus for the Trojan prince Paris. Menelaus assembled an army of all the greatest kings and heroes of Greece, and Odysseus was forced to join.

Penelope in the Odyssey

At the beginning of Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus has been absent from Ithaca for twenty years. Ten of those years were spent fighting the Trojan War—the trick of the Trojan Horse, which led to a Greek victory, was his idea—but nobody had heard from him since. Indeed, Odysseus’ return journey had been fraught with peril and setbacks: he spent ten years wandering the seas, losing all of his ships and men in the process.

Meanwhile, back in Ithaca, Odysseus was presumed dead. In the seventeenth year of his absence, the young men of Odysseus’ kingdom—108 of them in total, according to Homer[26]—flocked to his palace to seek Penelope’s hand in marriage. Though Penelope was by now much older than they were, she was still beautiful—and, of course, whoever married her would become king of Ithaca.

Though under immense pressure to remarry—even her father and brothers wanted her to do so[27]—Penelope was determined to remain faithful to Odysseus. She also wished to protect the inheritance of her son Telemachus, who was just entering adulthood.

Minerva Removes the Doubts of Penelope by Theodoor van Thulden, after Francesco Primaticcio (1632–1633).

RijksmuseumPublic DomainThe suitors did not make things easy on Penelope. They moved into her palace, ate her food, and tormented her servants. At one point, they even tried to murder Telemachus.[28] In public, Penelope remained steadfast in her resolve, regularly meeting with the suitors but never agreeing to marry; privately, she would mourn, fast, pray, and weep. At some points, she even wished for death:

Would that pure Artemis would even now give so soft a death, that I might no more waste my life away with sorrow at heart, longing for the manifold excellence of my dear husband, for that he was pre-eminent among the Achaeans.[29]

As the suitors grew increasingly persistent, Penelope devised crafty ways to delay them. First, she claimed that she could not remarry until she had woven a burial shroud for her father-in-law Laertes. She spent her days weaving, only to unravel all of her work at night while the suitors slept. This worked for a while, but eventually Penelope was betrayed by Melantho, one of her handmaids and a lover of the suitor Eurymachus.[30]

After being away for twenty years, Odysseus finally returned to Ithaca, three years into the suitors’ bid to win his wife. He first came to the palace disguised as a beggar, having learned from Athena that the place was crawling with suitors and that it would be dangerous for him to show himself.

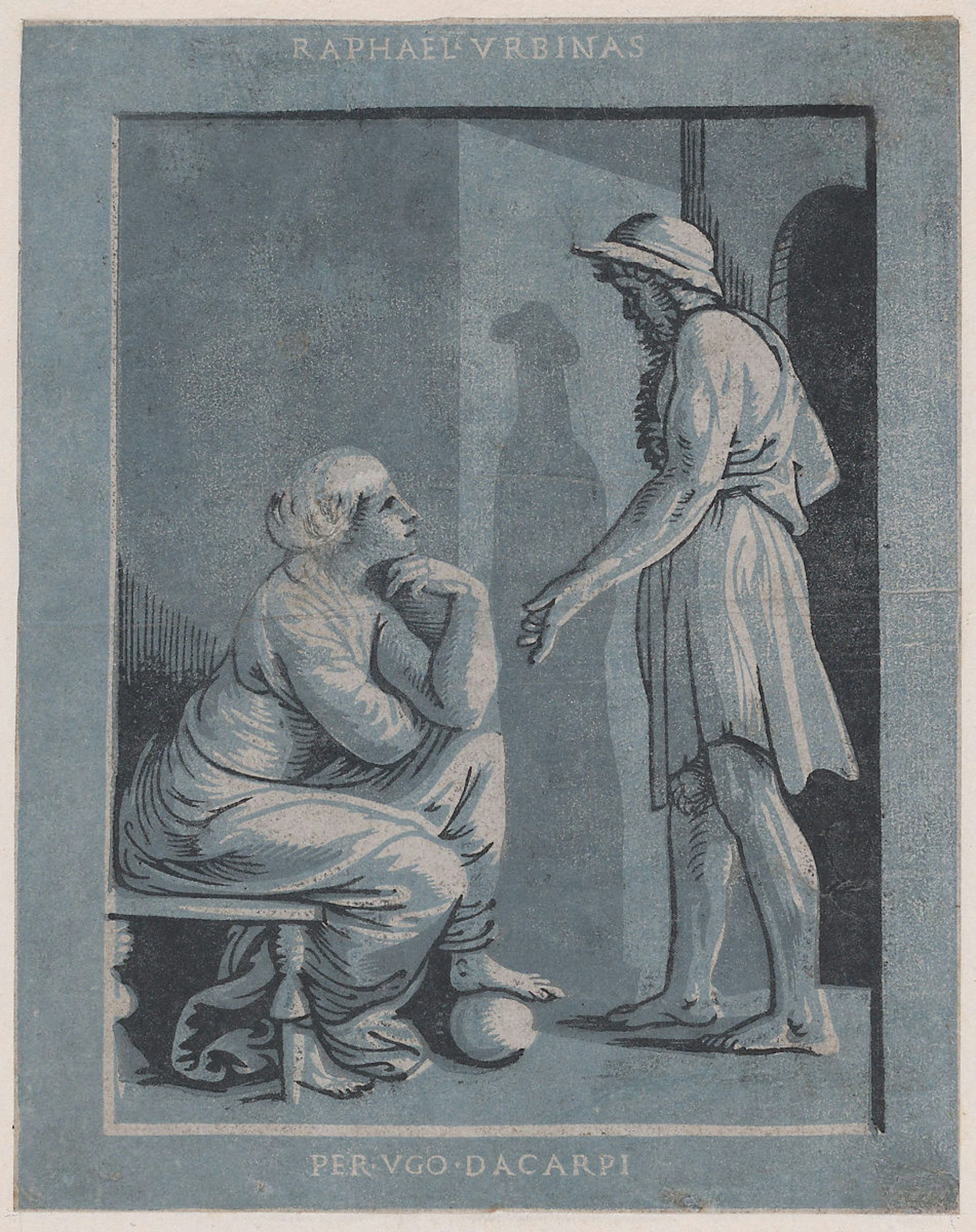

Penelope and Odysseus by Ugo da Carpi after Raphael (ca. 1520–1527).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOdysseus revealed his identity to his son Telemachus and a few trusted servants, but not to Penelope. He did, however, speak to her privately one night. During their conversation, Penelope told the disguised Odysseus that she planned to give the suitors one final test: she would marry whoever could string Odysseus’ old bow and shoot an arrow through twelve axe rings.[31]

With this information, Odysseus and Telemachus began plotting. They stole the suitors’ weapons and arranged for them to be locked in the main hall. When Penelope announced the test of the bow, none of the suitors could accomplish the task. Only Odysseus—still disguised as a lowly beggar—was able to string the bow and shoot an arrow through the axe rings. With his true identity revealed, Odysseus and Telemachus proceeded to slaughter all the suitors.[32]

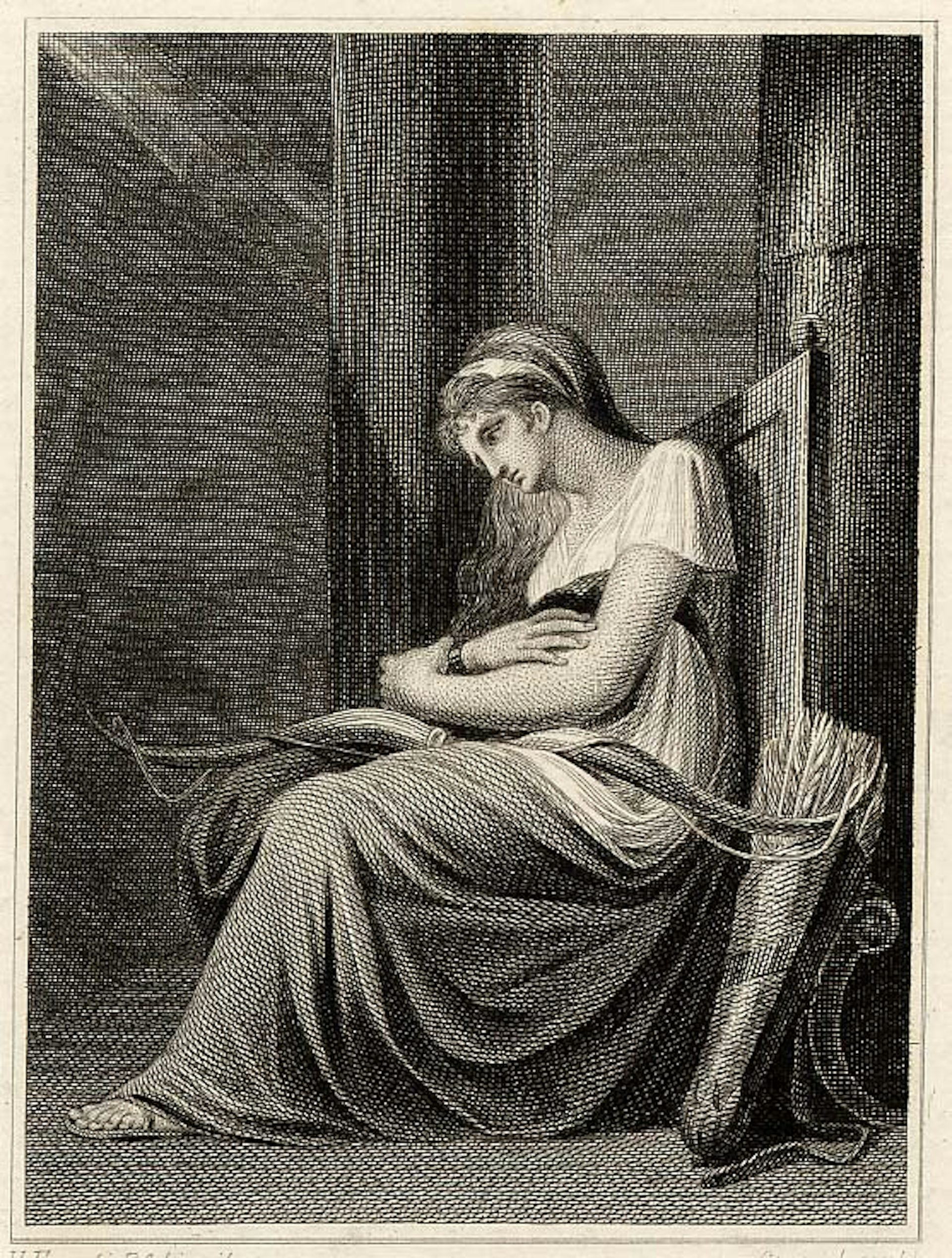

Penelope Holding the Bow of Odysseus by Robert Hartley Cromek after Henry Fuseli (1806). British Museum, London.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAfter the massacre, Odysseus revealed himself to Penelope. But Penelope was cautious; she had not seen Odysseus in twenty years and wanted to make sure that this man was really her husband. So she came up with a clever test: she told her servants to bring Odysseus’ bed outside to the main hall so that he could sleep there. When Odysseus told her that this was impossible, as he had built the bed out of a living olive tree (a fact that only the real Odysseus could have known), Penelope knew it was really him.[33]

Other Myths

In what survives of ancient Greek and Roman literature, there are only scattered references to what happened to Penelope after the events of the Odyssey. In what appears to have been a well-known tradition, Odysseus had no sooner returned to Ithaca than he was forced to leave again on another odyssey, this time to do penance for blinding Poseidon’s son Polyphemus.

Once again, Odysseus was absent from Ithaca for many years, though he eventually returned. Meanwhile, Odysseus’ son Telegonus—whom Odysseus had conceived with the sorceress Circe while making his way home from Troy—had come to Ithaca to find his father. Unfortunately, when they finally met, the father and son did not recognize each other, and Telegonus killed Odysseus.

When Telegonus discovered his mistake, he buried Odysseus and mourned his death. He then took Penelope and Telemachus with him to his mother’s island of Aeaea. There, Telemachus married Circe, while Telegonus married Penelope. Soon after, Penelope and Telegonus had a son named Italus, from whom Italy derived its name.[34]

Other Versions: Unfaithful Penelope

In some alternatives to the familiar Homeric account, Penelope was not faithful to Odysseus while he was away. There were different versions of what exactly she did, as well as her ultimate fate.

In some versions, Penelope slept with either Apollo, Hermes, or all of the suitors who came to court her in Odysseus’ absence. From this union, she gave birth to Pan, a half-goat woodland deity. In other versions, Penelope only slept with one of the suitors.[35]

When Odysseus came home and discovered that Penelope had been unfaithful, he either banished her,[36] killed her,[37] or left Ithaca to continue his wanderings.[38]

Pop Culture

Penelope continues to be evoked in modern pop culture. Her myth has been turned into operas by Alessandro Scarlatti (1676), Gabriel Fauré (1913), and Rolf Liebermann (1954). She has also appeared in film and television adaptations of the Odyssey, including the film Ulysses (1954), the miniseries The Odyssey (1997), and several episodes of the 1990s television series Xena: Warrior Princess.

Penelope has featured in literary retellings of the Odysseus myth as well, such as Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel (1938), Eyvind Johnson’s Return to Ithaca (1946), and Glyn Iliffe’s Adventures of Odysseus series (2008–2017). Most notably, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad (2005) tells the story of Homer’s Odyssey from Penelope’s point of view.

As in the familiar ancient tradition, these modern Penelopes are defined by their virtue and faithfulness. Penelope must await her husband patiently and, above all, chastely, even as Odysseus takes several divine lovers during his travels—including Circe and Calypso—without a second thought. Modern authors have sometimes tried to problematize this double standard: Atwood’s Penelope, for example, expresses bitterness at being faithful to a fault for twenty years while her husband felt no obligation to do the same.