Hera

Etruscan red-figure calyx krater by the Painter of London F484 (ca. 420–400 BCE) showing Apollo (left), Zeus (center), and Hera (right)

National Archaeological Museum, Madrid / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5Overview

Hera—the sister and wife of mighty Zeus—served as the queen of the Olympian deities and the goddess of women, family, and marriage. She was also the patron of the city of Argos; it was here that her worship in the ancient world was the most vibrant.

“Cow-eyed”[1] Hera was usually represented as a stately queen with robe and headdress. In myth, she was remembered as a jealous goddess who was forever tormenting her husband’s many lovers and illegitimate children. Figure 1

Key Facts What were Hera’s attributes?

Hera cut a regal figure with her traditional attributes of a robe or cloak, crown or headdress, and scepter. She was sometimes depicted with a peacock or even riding in a peacock-drawn chariot.

In mythology, Hera was presented as bold, clever, and powerful, yet she was best known for her less flattering characteristics. Above all else, Hera was a jealous and vengeful goddess who struggled with her husband's infidelities and raged (often fruitlessly) against his many lovers, both mortal and divine.

Statue of the Hera Borghese type, Roman copy after a 5th century BCE Greek original

Vatican Museums / Rabax63CC BY-SA 4.0Who were Hera’s children?

Hera bore several children to her husband Zeus, including Ares, the god of war; Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth; and Hebe, the goddess of youth. The smith god Hephaestus was also Hera’s son, though ancient sources disagreed on his exact paternity: some traditions made him the son of both Hera and Zeus, while others made him the son of Hera alone, born without a father.

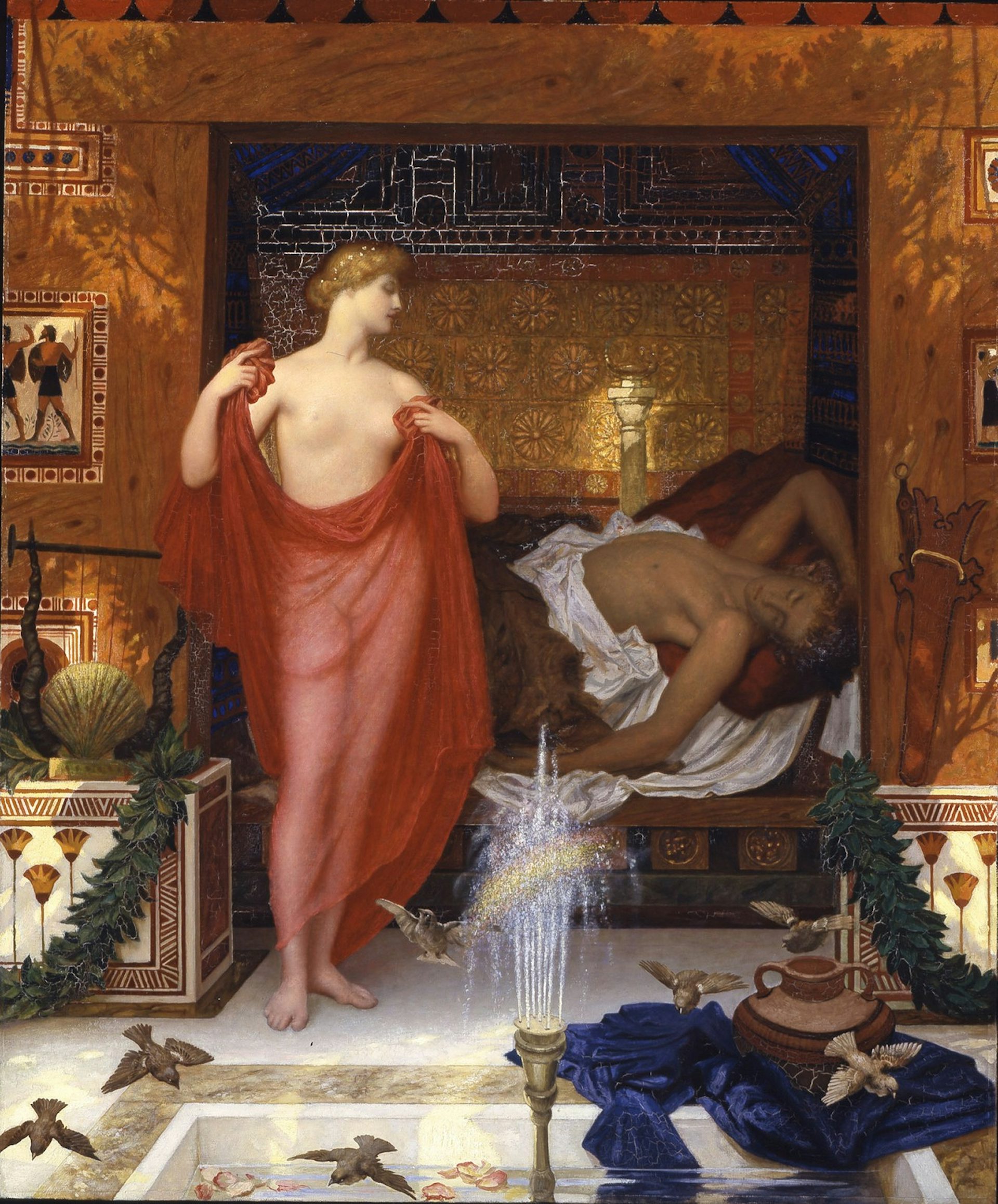

Hera in the House of Hephaistos by William Blake Richmond (1902)

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, INPublic DomainHera and Io

Hera was forever waging war against her husband’s illicit lovers and illegitimate children. In one myth, Hera discovered that Zeus was having an affair with Io, a mortal girl from Argos and Hera’s own priestess. When Hera angrily confronted Zeus, Io was somehow transformed into a cow (there are different versions of who was responsible for this transformation).

Io’s metamorphosis, though dramatic, was not enough for Hera; the jealous goddess also had her rival held prisoner. When the guard, Argus Panoptes, was killed at Zeus’ behest, Hera had Io pursued across the world by an unrelenting gadfly. In the end, Io reached Egypt, where she was restored to her original shape and allowed to live out her life in peace.

Juno Discovering Jupiter with Io by Pieter Lastman (1618)

National Gallery, LondonPublic DomainRoles and Powers

Hera was revered as a goddess of women, marriage, and motherhood, but also as a protector of cities and young men. As the wife of Zeus, she was the queen of the Olympian gods.

Hera held sway over many domains, but her principal responsibilities lay in the realm of marriage and married life. She was sometimes connected with childbirth in the guise of “Hera Eileithyia” (in mythology, Eileithyia—the goddess of childbirth—was Hera’s daughter). By comparison, her connection to unmarried maidens and motherhood was less prominent, even though she was thought to preside over all aspects of female life.

Another function of the goddess was protection of the polis, or city-state, and its young male warriors. This role was especially important in her major cult centers at Argos and Samos.

Photo of the remains of the Heraion on the Inachus Plain near Argos

Sarah MurrayCC BY-SA 2.0Attributes

For the ancients, Hera was distinguished by her queenly qualities.[2] She was typically imagined crowned and clad in regal robes; in one tradition, it was the goddess Athena herself who wove Hera’s raiment.[3] She lived with the other Olympian gods on Mount Olympus, in a palace befitting her station.

Hera’s favorite cities, according to Homer, were Argos, Mycenae, and Sparta.[4] Argos in particular was a very early and important cult center of the goddess (see below).

Because she was a goddess of all aspects of female life, some local traditions claimed that Hera could restore her own virginity and become a maiden again. The goddess accomplished this by bathing annually in the spring of Canathus, in the Argolid.[5]

From the earliest periods of Greek history, Hera was associated with cattle—hence her Homeric epithet “cow-eyed” (see below). In this way, Hera is comparable to the Egyptian Hathor, a cow-faced goddess of motherhood.

Hera was also associated from early on with the cuckoo bird, as it was said that Zeus had seduced her in the form of a cuckoo. A cuckoo sat on top of Hera’s scepter in many of her cult images.[6] The goddess was also connected with peacocks, horses, and lions.

Juno and the Peacock by Wenceslaus Hollar (17th century)

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, TorontoPublic DomainIn myth, Hera’s most recognizable characteristics were her jealousy and vengefulness—traits amplified by her husband Zeus’ many affairs. Indeed, much of Hera’s mythology tells of the wrath she visited upon Zeus’ lovers and illegitimate children.

Classics scholar Timothy Gantz describes Hera as “rather severe, not generally inclined to offer assistance to mortals and certainly with no sense of humor”—though he admits that “perhaps her marital situation is sufficient cause for that.”[7]

Among Hera’s closest companions was Hebe, the goddess of youth (and Hera’s own daughter). Hebe frequently served as Hera’s attendant; in the Iliad, for example, Hebe is depicted helping Hera yoke her wagon.[8] She is also described as Hera and Zeus’ cupbearer, thus becoming a kind of female counterpart to Ganymede, the male cupbearer of the gods.[9]

Iconography

In her iconography, Hera was generally represented wearing a peplos (a sleeveless dress or robe) and himation (a cloak). Her himation was usually pulled over her head like a veil. She was also shown wearing a crown (pōlos or stephanē) and carrying a scepter, a libation bowl (phialē), or a pomegranate.

Head of Hera with diadem. Marble, Roman Imperial Era copy after 5th century BCE Greek original.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFrom the Hellenistic period on, it was common to depict Hera riding in a chariot drawn by peacocks (though this imagery only appeared after the eastern conquests of Alexander the Great, since peacocks were unknown in Greece before then).

Though one of the most important goddesses of the Greek pantheon, Hera was not typically shown on her own. In depictions of the assembled gods, she almost always appeared alongside Zeus, underscoring her role as his companion. Indeed, Hera was often depicted in hieros gamos (“sacred marriage” or “hierogamy”) scenes together with her husband/brother Zeus.

Few cult images of Hera survive. In early Greece, she was occasionally represented aniconically (that is, without an image). In Argos, for example, she was represented as a pillar, and on the island of Samos as a plank. Eventually, these humble images were replaced by more impressive statues, such as the beautiful chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Hera that Polyclitus fashioned for Hera’s temple in Argos.[10]

Hera was also featured in artistic renderings of various mythical scenes. In representations of the Judgment of Paris, for example, she appeared as one of the three goddesses vying for the infamous golden apple.

Some representations of the Gigantomachy, including those on the Siphnian Treasury and the Pergamon Altar, showed Hera fighting the Giants alongside the other gods. She was sometimes also shown in depictions of the return of Hephaestus or, more rarely, in scenes from the mythology of Heracles.[11]

Etymology

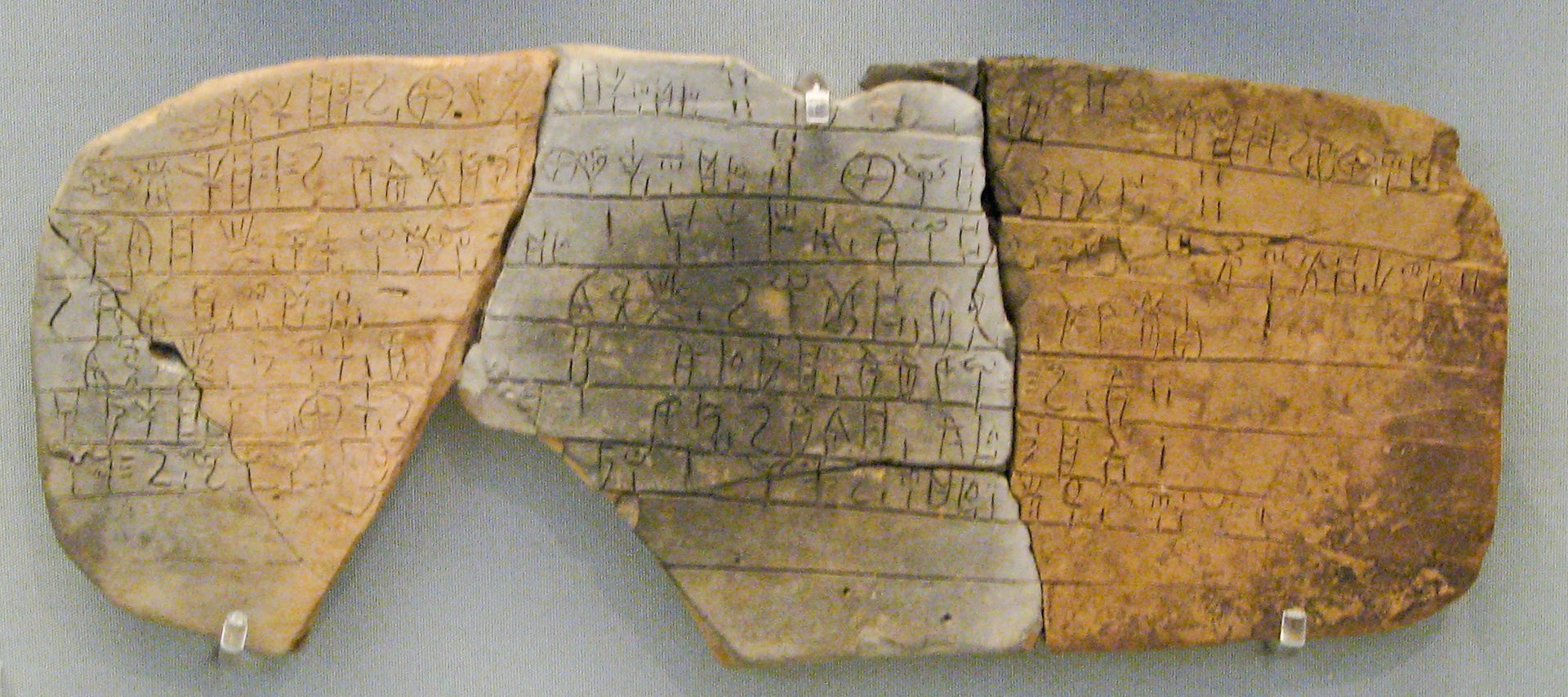

The etymology of the name “Hera” (Greek Ἥρη or Ἥρα, translit. Hḗrē or Hḗra) is uncertain. The name itself is very old, dating back to the Mycenaean period; it can be found on tablets written in Linear B, the script used to write the earliest known form of the Greek language. Scholars have most often translated E-ra—the Linear B version of Hera—as “mistress” or “lady,” but the precise origin and meaning of this term remain controversial.

Clay Linear B tablet from Pylos (PY Ub 1318)

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / Sharon MollerusCC BY 2.0Some ancient authorities—especially philosophers and allegorists—rearranged the letters of Hera’s name to link the goddess to ἀήρ (aḗr), the Greek word meaning “air.” Alternatively, Hera was identified as ἐρατή (eratḗ), “the lovely one.”[12] But modern scholars dismiss these as folk etymologies.

More recently, some scholars have posited that Hera’s name is a feminine form of the Greek word hērōs, “hero.” The more remote derivation, based on the Indo-European root *yer- (“year” or “spring”), suggests that the goddess’s name means something like “goddess of the year.” Either way, it is likely that the name itself is pre-Greek in origin.[13]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Hera Ἥρη or Ἥρα (Hḗrē or Hḗra) Phonetic

IPA

[HEER-uh, HER-uh] /ˈhɛrə, ˈhɪərə/

Alternate Names

In ancient Greece, Hera was called either Ἥρη (Hḗrē) or Ἥρα (Hḗra). The precise form of the name varied according to local dialects and conventions.

Hera’s Roman equivalent was Juno (Latin Iuno).

Titles and Epithets

As a goddess of all aspects and stages of female life, Hera could be invoked under a variety of titles and epithets, many of them contradictory. Hera was thus simultaneously the “maiden” (παῖς/paîs), “bride” (νυμφευομένη/nympheuoménē), “wife” (τέλεια/téleia or ζύγια/zýgia), and “widow” (χήρα/chḗra).

In her capacity as queen of the gods, Hera was often addressed as βασίλεια (basíleia), “queen.”

Hera also possessed poetic and epic epithets that referred to her beauty, including λευκώλενος (leukṓlenos), “white-armed,” and βοῶπις (boôpis), “cow-eyed” or “cow-faced.”[14]

Family

Hera was the daughter of Cronus and Rhea—Titans who overthrew the primordial deities Uranus and Gaia to establish themselves as rulers of the universe. Her siblings included the gods Hestia, Demeter, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus.[15]

Hera married her brother Zeus, who went on to become king of the gods.[16] Their marriage produced several children, including Eileithyia, goddess of maternity and childbirth; Hebe, goddess of youth; Hephaestus, god of the forge; and Ares, god of war (though in some traditions, Hephaestus and Ares did not have a father).[17]

Zeus and Hera on Mount Ida by Andries Cornelis Lens (1775)

Kunsthistorisches Museum, ViennaPublic DomainMore obscure traditions also made Hera and Zeus the parents of Angelos,[18] Eleutheria (the personification of freedom),[19] Eris (the personification of discord),[20] the Charites or “Graces” (usually the daughters of Zeus by Themis),[21] the Curetes,[22] and even Heracles.[23]

As the goddess of marriage, Hera did not generally have extramarital affairs (in contrast to her polyamorous husband Zeus). There were, however, various figures from myth who tried to seduce Hera, including Ixion and Endymion—both of whom were punished for their trouble.

In one lesser-known story, Hera was raped by the Giant Eurymedon and bore him a son, Prometheus (in the more familiar version, Prometheus was the son of one of the Titans, not of Hera).[24]

Hera also (begrudgingly) nursed some of the children born to her husband Zeus from his other lovers. For instance, there were stories of Hera nursing Heracles (the son of Zeus and Alcmene), Hermes (the son of Zeus and Maia), and Dionysus (the son of Zeus and Semele).[25]

The Origin of the Milky Way by Jacopo Tintoretto (ca. 1575)

National Gallery, LondonPublic DomainFinally, Hera sometimes appeared in myth as the mother or foster mother of monsters. In some traditions, for example, she was the mother of the monster Typhoeus (Typhon), who did battle with Zeus.[26] Hera was also the foster mother of the Nemean Lion and the Hydra, two of Heracles’ most fearsome adversaries.[27]

Mythology

Origins

Hera belongs to the earliest stratum of Greek deities. She is attested in the Linear B tablets of the Mycenaean period (see above), especially those found at Pylos and Thebes.[28]

It is possible that the Mycenaean Hera was already the consort of Zeus even during this early period; at Pylos, she is named in connection with Zeus. Hera and Zeus may have been the parents of a god named Drimios (di-ri-mi-jo in Linear B), though this deity is completely unknown in later Greek sources.[29]

It is unclear when exactly Hera’s cult was introduced to Greece or what functions she originally performed. She may have been worshipped independently before being reinvented as the consort of the supreme god Zeus.

Birth and Early Years

Hera was among the younger children of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. At the time of her birth, Cronus ruled the cosmos. But upon hearing a prophecy that one of his children would overthrow him, Cronus decided to swallow each of them as soon as they were born—including Hera. Only Zeus was able to escape.

When Zeus was fully grown, he tricked his father into regurgitating his siblings—Hestia, Demeter, Poseidon, Hades, and Hera—and together they revolted against Cronus and the Titans. After a ten-year war known as the Titanomachy, the gods were finally victorious. With Zeus as their king, they became the Olympians (so called because they lived atop Mount Olympus).[30]

Titan Struck by Lightning by François Dumont (1712)

Louvre Museum, ParisPublic DomainHera’s role in the war with the Titans is unclear, though it seems that she mostly kept out of the fighting. According to Homer, Hera was raised by the aloof Titans Oceanus and Tethys while her brother and father warred with one another.[31] In other traditions, Hera was brought up by a nymph called Macris on the island of Euboea.[32]

Marriage and Children

Hera and Zeus

After his prior marriages to Metis and Themis had ended, Zeus set his sights on his beautiful sister Hera. But Hera did not immediately give in. Different traditions describe how Zeus finally managed to win her hand.

In some stories, Zeus and Hera first began sleeping together in secret, when Hera was still living in the home of her parents.[33] In another story (from the city of Argos), Hera originally resisted Zeus’ advances, so Zeus resorted to cunning to win her over.

Zeus transformed himself into a cuckoo and came to Hera’s window on a rainy night. When she saw the shivering bird, Hera took pity on it and clasped it to her bosom. Once Zeus revealed himself, Hera finally agreed to marry him.[34]

Hera and Zeus were wed in a glorious ceremony, the prototypal “sacred marriage.” It was said that the Moirae (the “Fates”) married the couple, while Eros, the god of love, drove the wedding chariot.[35] The marital bed was prepared by Iris.[36] The couple received gifts from all of the gods, including the golden apples that Hera kept in the Garden of the Hesperides—a present from the earth goddess Gaia.[37]

A fourth-style fresco from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii, showing the marriage of Zeus (right, seated) and Hera (center, standing)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0According to a local Cretan tradition, the wedding ceremony took place on Knossian territory, and a temple was built on the site to commemorate the occasion.[38] But there were also other places that claimed to be the site of the marriage (or the first sexual union) between Hera and Zeus, including Samos,[39] Naxos,[40] Euboea,[41] Hermione,[42] and Mount Cithaeron.[43]

Hera and Zeus had a notoriously strained relationship. In some myths, Hera even tried to overthrow her husband. One version of the Typhoeus myth, for instance, made Typhoeus a child of Hera, begotten by her independently (that is, without a father) for the express purpose of destroying Zeus. But Zeus defeated Typhoeus in the end.[44]

In another myth, Hera and several other Olympians revolted against Zeus. While the king of the Olympians was asleep, Hera and her allies stole his thunderbolts and bound him tightly. But Zeus was ultimately saved by the sea goddess Thetis (the mother of Achilles) and Briareus, one of the hundred-handed creatures known as the Hecatoncheires. Once free, Zeus took up his thunderbolts and cowed the rebellious gods into submission.[45]

In a Boeotian myth associated with the local Daedala festival, one of the quarrels between Hera and Zeus was so terrible that Hera fled to her childhood home in Euboea and refused to return.

Seeking to get his wife back, Zeus turned to Cithaeron, the wisest living mortal (or, in an alternative version, to Alalcomeneus, the first man of western Boeotia). Cithaeron advised Zeus to fashion a wooden image of a woman, dress it as a bride, and have it pulled in an oxcart while spreading the word that he was going to marry the nymph Plataea.

Kithaeron by Willoughby Vera (1925)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainZeus followed Cithaeron’s advice. When Hera saw her husband’s new “bride,” she tore off the nymph’s veil in a fit of jealousy. She was so relieved to find that Plataea was merely a wooden statue that she agreed to make amends with Zeus.[46]

Many other myths were told about the ongoing quarrels between Hera and Zeus, most of them pertaining to Hera’s (understandable) anger over Zeus’ many affairs.

The Children of Hera

Together with Zeus, Hera had several children, including the gods Ares, Eileithyia, and Hebe. Interestingly, these were never regarded as the most important or accomplished of Zeus’ children. His offspring by other goddesses or women, such as Apollo and Artemis (his children by Leto), Dionysus (his son by Semele), or even Heracles (his son by Alcmene), were much more prominent among the gods.

Hera had complex relationships with her offspring. She had a particularly close connection with Hephaestus, the god of metallurgy and craftsmanship, who was often seen in ancient literature supporting his mother and making presents for her.[47]

Hera was often said to have conceived Hephaestus independently or asexually, without a male partner. According to the familiar tradition, she did this in a fit of jealous rage, as she was upset with Zeus over the similarly unusual and fantastic birth of Athena, who was born from Zeus’ head.[48]

Unfortunately, Hephaestus was not a particularly good-looking god, and his malformed feet and garish appearance were sometimes connected to his (literal) fall from Mount Olympus: in one tradition, Hera was so disgusted by her child’s lameness that she threw him to the earth.[49]

Zeus with Hera Expelling Hephaestus by Gaetano Gandolfi (1761–1769)

National TrustPublic DomainIn some traditions, Hephaestus sought to enact revenge upon his mother. He built a clever trap for Hera, which consisted of a throne with invisible chains strapped around it; when Hera sat upon this throne, she suddenly became bound to it.

She was eventually freed through the intervention of the new god Dionysus, who plied Hephaestus with wine and brought him back to Olympus to free his mother. Hephaestus was ultimately given the beautiful Aphrodite as his bride, which may have been a reward for releasing Hera.[50]

Hera and the Heroes

Hera’s Revenge(s) on the Lovers and Children of Zeus

Much of Hera’s mythology deals with her acts of revenge against her husband’s many illicit lovers and children. Though Hera’s jealousy was certainly justifiable, her vindictive treatment of these rivals—who were often powerless to defend themselves—painted the goddess in a cruel and petty light.

Leto

One of Zeus’ lovers was Leto, daughter of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe. When Hera discovered Leto was pregnant with her husband’s child, she tried to prevent her from giving birth; Hera swore to unleash her fury upon any land or people that agreed to take in the beleaguered goddess.

Attic black-figure amphora showing (left to right) Dionysus, Artemis, Apollo, Leto, and Hermes; related to the Antimenes Painter (ca. 510 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEventually, Leto managed to escape to the barren island of Delos, which agreed to give her shelter in exchange for being made the sacred island of Leto’s unborn son Apollo. Not willing to give up, Hera detained her daughter Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, so as to further protract Leto’s labor. In the end, Leto finally gave birth to Apollo and Artemis, who ascended to Olympus to join the other powerful gods.[51]

Io

Another popular myth saw Hera seeking revenge against Io, one of her own priestesses from the city of Argos, who had been ravished by the insatiable Zeus. When Hera caught wind of the affair, she searched high and low for Io, but was unable to find her. Zeus—who by now was well practiced in sneaking around on his wife—had transformed the young lady into a cow.

Not to be outdone, Hera sent her henchman Argus Panoptes, a creature with a hundred eyes, to find and imprison the transformed Io. Zeus, in turn, sent Hermes to kill Argus and free Io. Hera responded by sending a gadfly to pester Io, who traveled all the way to Egypt to escape the persistent insect. At last, in Egypt, Io was restored to her human form by Zeus, after which she gave birth to a son named Epaphus.[52]

Callisto

In a similar myth, Hera sought to punish Zeus’ Arcadian lover Callisto. The details of Callisto’s myth vary considerably depending on the source, but in virtually all versions, she was transformed into a bear (either by Zeus, as in the Io myth, or by Hera herself). In bear form, Callisto was then hunted by either the hunter goddess Artemis or, more perversely, by her own son Arcas, who did not recognize his mother in her changed form.

Diana and Callisto by Jakob Kellner (1763)

Slovak National Gallery, BratislavaPublic DomainIn some accounts, Callisto’s suffering was ended when Zeus turned her into the constellation Ursa Major, the “Great Bear.” But even then, Hera refused to let her go, securing from the sea goddess Tethys a promise that Ursa Major would never be permitted to bathe in the waters of the ocean.[53]

Semele and Dionysus

Another of Zeus’ lovers, the Theban princess Semele, was punished using deception. The jealous Hera approached Semele in disguise (in some versions, she assumed the form of Semele’s elderly nurse) and urged her to have Zeus prove his identity by revealing himself in his true form.

Semele foolishly took the disguised Hera’s advice and made Zeus promise to fulfill any request she made. She then demanded to see the god in his true form. Unable to break his promise, Zeus revealed himself to Semele; as a mortal, she could not endure the sight and burst into flames.

Zeus was forced to remove his unborn son Dionysus from Semele’s womb and sew him into his own thigh until he was ready to be born.[54]

When Dionysus at last emerged from Zeus’ thigh, Hera sought to punish the child, too. She destroyed his foster parents Ino and Athamas and drove Dionysus himself mad. Dionysus wandered the world for some time, hounded by Hera’s anger, before discovering wine and joining the Olympian pantheon.[55]

Roman sarcophagus showing the triumph of Dionysus (ca. 190 CE)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0Heracles

Perhaps the most famous and extensive myth of Hera’s revenge centers on the goddess’s pursuit of Heracles, son of Zeus and the mortal princess Alcmene. Hera and Heracles are inseparable from one another’s mythologies; in fact, the very name “Heracles” can be translated as “Hera’s glory.”

Even before Heracles was born, Hera began plotting against him. She sent her daughter Eileithyia to extend Alcmene’s labor so that the child would lose his claim to the throne of Mycenae.[56] Soon after Heracles’ birth, Hera sent a pair of snakes to kill him. But the precocious demigod strangled the snakes—an early indication that he was destined for great things.[57]

Hera continued to torment Heracles when he reached adulthood. It was Hera who drove Heracles mad, causing him to kill his children (and, in some traditions, the children’s mother Megara too).[58] To atone for this terrible deed, Heracles was forced to perform ten (later twelve) labors for his enemy Eurystheus, now the king of Mycenae.

Hera masterminded many of Heracles’ famous labors, too. For example, she reared the Nemean Lion[59] and the Hydra,[60] hoping that they would be strong enough to kill Heracles (they were not). When Heracles went to the land of the Amazons for the girdle of Hippolyta, Hera made sure to incite the Amazons against Heracles so the quest would be even more daunting.[61]

In addition, when Heracles was driving Geryon’s cattle back to Greece, Hera sent a horsefly to goad the cattle so that they escaped, forcing Heracles to round them up again (with great difficulty).[62]

Hercules and the Nemean Lion by Peter Paul Rubens (17th century)

National Museum of Art of Romania, BucharestPublic DomainIn one myth, Hera went too far, sending a storm that nearly drowned Heracles as he was sailing across the Aegean. Zeus was so angry at Hera for this act that he suspended her from the top of Mount Olympus with golden chains, tying anvils to her feet.[63]

One old but obscure myth tells of how Hera once attacked Heracles face-to-face in Pylos. This did not go well for the goddess, who left the battle injured when Heracles shot her with an arrow that pierced her right breast.[64]

As these stories make clear, the relationship between Hera and Heracles was quite hostile. But this prevailing hostility was sometimes interrupted or undermined by moments of friendliness. For instance, Hera was sometimes said to have nursed the newborn Heracles.[65]

Heracles himself came to Hera’s assistance on a few occasions, such as when he stopped the Giant Porphyrion from raping the goddess during the Gigantomachy,[66] or when he rescued Hera from a gang of lustful satyrs.[67] Various sanctuaries and monuments of Hera were associated with Heracles, and some were even said to have been dedicated by the hero.[68]

In the end, once Heracles had overcome all of Hera’s plots against him and been transformed into a god, he reconciled with Hera. He even married her daughter Hebe, thus becoming the son-in-law of his lifelong enemy.[69]

The Apotheosis of Hercules by Noël Coypel (ca. 1700)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOther Lovers and Children of Zeus

There were other, more obscure stories of Hera’s vengeance against the lovers or children of Zeus. Some later authors, for instance, told of how Hera destroyed the population of the island of Aegina when she discovered that Aeacus, the island’s king, was a son of Zeus and the nymph Aegina.[70]

In another story, Hera’s revenge claimed collateral damage when she punished the nymph Echo for distracting her from catching Zeus with one of his lovers. Since Echo had detained Hera by chatting to her, Hera made it so that Echo would be able only to repeat (or “echo”) whatever others said to her.[71]

Hera as Benefactor

More rarely, Hera appeared in myth as a benefactor or patron of the few mortals or deities who were dear to her heart.

The Argonauts

Hera loved the hero Jason and supported him against Pelias, his uncle and rival for the throne of Iolcus in Thessaly.[72] Hera hated Pelias as much as she cherished Jason, for Pelias had—at least in some traditions—ignored her when making sacrifices to the gods.[73]

Panel by Jacopo del Sellaio (c. 1465)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhen Jason returned to Iolcus from exile, Hera met him at a nearby river, disguised as an old woman. Though Jason did not recognize the goddess, he helped her cross the river by carrying her on his shoulders, losing one of his sandals in the process. When he later reached Iolcus, he inspired terrible fear in Pelias, who had learned from an oracle that a man wearing only one sandal was destined to take away his throne.[74]

To neutralize the threat he saw in Jason, Pelias sent the young man to retrieve the Golden Fleece from Colchis—a mission he regarded as impossible. Undaunted, Jason commissioned a ship, the Argo, to make the arduous voyage, and put together a team of heroes to accompany him. These heroes were called the “Argonauts,” after the ship on which they sailed.

The Argonauts faced many dangers on their journey, but Hera looked after them and made sure that they completed their mission. In some accounts, she helped push the Argo through the Symplegades, two cliffs that clashed together and crushed whatever passed between them.[75]

It was also Hera who ensured that the Colchian princess Medea fell in love with Jason and helped him steal the Golden Fleece from her paranoid father Aeetes.[76] The Argonauts, in turn, built sanctuaries to Hera at Argos and on Samos.[77]

Hera was quite fond of Medea, possibly because Medea had rejected Zeus when he tried to seduce her. In one tradition, Hera promised Medea that she would make her children immortal. Medea thus left each of her offspring in the temple of Hera as soon as they were born.

Unfortunately, the children all died—though they were worshipped afterwards by the people of Corinth. Thus, they did become immortal in a sense, even if not in the way that Medea had hoped.[78]

The Trojan War

Hera also loved Achilles and the other Greek heroes who fought in the Trojan War. Years before the war broke out, the Nereid Thetis earned Hera’s favor by rejecting the amorous advances of Zeus; as a reward, Hera gave Thetis in marriage to the hero Peleus (a former Argonaut).[79] Thetis and Peleus later became the parents of Achilles.

Detail from an Attic red-figure kylix showing Peleus capturing Thetis as she changes shape, attributed to Douris (ca. 490 BCE)

Cabinet des Médailles, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainIt was at the wedding of Thetis and Peleus that the events leading to the Trojan War were first set in motion. During the wedding—a lavish affair attended by all the gods—a quarrel erupted between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite: the three goddesses each thought that they deserved a golden apple inscribed with the words “to the fairest.”

This apple had been brought to the wedding by Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, who was angry that she alone of all the gods had not been invited. Eris knew that the apple would ignite a vicious feud—a fitting punishment for the gods who had slighted her.

The three goddesses turned to the Trojan prince Paris to judge their contest and decide which of them deserved the apple, a myth now known as the “Judgment of Paris.” Paris awarded the apple to Aphrodite, goddess of love and sexuality, who had promised him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world as a reward.[80]

Unfortunately, the most beautiful woman in the world was Helen, who was already married to the Spartan king Menelaus. When Paris seduced Helen and carried her off, Menelaus assembled an army of all the kings of Greece and sailed to Troy to win her back.

Hera, who nursed a bitter resentment towards Paris and the Trojans for the unfavorable results of the beauty contest, lent her considerable might to the Greeks over the course of the long conflict. She helped assemble the massive Greek (or “Achaean”) force[81] and continued to support them at Troy. In the Iliad, Hera’s ruthless hatred of the Trojans causes her to bicker and quarrel with Zeus on more than one occasion.[82]

Iris Approaching Athena and Hera, attributed to Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée (ca. 1780)

MiA (Minneapolis)Public DomainIn one famous episode, Hera attempted to deceive Zeus, who had forbidden the gods from interfering in the conflict. First, she lured him into bed; she then persuaded Hypnos, the embodiment of sleep itself, to keep Zeus asleep so that she could meddle in the war, sending her brother Poseidon to help the Greeks turn back the Trojans.

When Zeus awoke, he was furious. He called back Poseidon and threatened to punish Hera severely if she ever tried her tricks on him again.[83]

Eventually, after ten years of fighting, the Greeks finally sacked Troy. Hera rejoiced to see the hated city in ruins, though her own attempts to sway the tides of war had mostly been abortive. In the end, Troy fell because it was destined to fall.

Other Myths

Though the bulk of Hera’s mythology is centered on her power struggles with Zeus, there are other myths in which she also plays a part.

One of the charter myths of Hera’s beloved Argos tells of how the early Argive king Phoroneus chose Hera over Poseidon as the city’s patron deity. Poseidon retaliated by flooding the land until Hera interceded and soothed his wrath.

In an alternative tradition, Poseidon punished the Argives by ensuring that their land would be dry and barren for much of the year—though he later gave them the spring of Lerna, perhaps as recompense for his earlier punishment.[84]

Hera, like the other Olympians, took part in the Gigantomachy, the conflict between the Olympian gods and the monstrous Giants who wished to unseat them. During the battle, it was said that Porphyrion, the king of the Giants, tried to rape Hera. He was promptly killed by Zeus—with the help of none other than Heracles, Hera’s old enemy.[85]

Hera shown fighting against the Giants on the east frieze of the Pergamum Altar (first half of the 2nd century BCE)

Pergamon Museum, Berlin / Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0In one story, Zeus honored the mortal Ixion, king of a northern Greek tribe called the Lapiths, by hosting him on Mount Olympus. While there, Ixion fell in love with Hera and attempted to seduce her. But his plan backfired when the gods discovered his desire.

Zeus fashioned a replica of Hera from the clouds and presented it to Ixion, who proceeded to have his way with what he thought was Hera. From this union were born the half-horse, half-human Centaurs. For his insolence, Ixion suffered a terrible punishment: he was tied to a fiery wheel that spun endlessly for all eternity.[86]

A similar myth was sometimes told about the Elean hero Endymion. Like Ixion, Endymion was admitted to the company of the gods, but had the misfortune of falling in love with Hera. To punish him, Zeus either cast him down into the Underworld or caused him to fall into an eternal sleep.[87]

The Sleep of Endymion by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1791)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowCC BY-SA 3.0Many other myths showcased Hera’s well-attested vengeful nature. In one story, Hera drove the daughters of the Argive king Proetus mad when they foolishly boasted that their father was wealthier than the goddess (or, alternatively, when they mocked an old wooden image of the goddess or claimed to be more beautiful than she). The princesses only regained their sanity after Proetus made numerous sacrifices (or, in some traditions, through the assistance of the seer and healer Melampus).[88]

On a few occasions, Hera punished mortal women who claimed to be more beautiful than she. Antigone, the daughter of the Trojan king Laomedon, made this foolish boast and was promptly turned into a stork. (In another version, Hera turned Antigone’s hair into snakes, and it was the other gods who took pity on the girl and turned her into a stork.)[89] When Side, the wife of the hunter Orion, committed this same offense, Hera sent her to the Underworld.[90]

In another strange myth, Hera and Zeus got into an argument over which sex, male or female, experienced more pleasure during intercourse. To settle the question, they turned to Tiresias, who had lived as both a man and a woman. When Tiresias confirmed that it was females who experienced more pleasure, the furious and humiliated Hera struck him blind.[91]

Worship

Temples

Hera’s temples—called Heraea (Heraeum in the singular)—were some of the oldest and most impressive of the ancient Greek world. Most of these temples were located outside of the settled areas of the city. This was likely due to Hera’s role as the protector of the city, as well as certain cult practices.

The Heraeum of the island of Samos, the earliest roofed temple built by the Greeks, dates from around 800 BCE. Though this temple was destroyed, it was rebuilt on an even grander scale in the sixth century BCE.[92] Hera’s cult image at Samos has been cited as evidence of the temple’s tremendous age: it was said to have been fashioned in the time of the mythical craftsman Daedalus.[93]

Another important temple of Hera, also called a Heraeum, was in Argos, situated on a hill some distance from the main city. This was likewise a very ancient structure, built during the seventh century BCE, if not earlier.[94] Hera had other major temples nearby in the Argolid and the Peloponnese, where her worship was especially prominent, including in cities such as Perachora, Sparta, Corinth, and Tiryns.

Hera had a famous temple in Olympia, where the Olympic Games were held every four years.[95] She also had a temple on the sacred island of Delos.

The cult of Hera was particularly important in Dorian and Achaean cities, including cities outside of the Greek peninsula and Aegean islands. In Paestum in southern Italy, for example, there was a temple complex of three monumental temples, two of which were Hera’s. The nearby cities of Metapontum and Croton also had temples of Hera, as did some Sicilian cities such as Selinus.

Temple of Hera II (ca. 450 BCE). Paestum (modern Salerno, Campania).

Norbert Nagel / Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 3.0At some of her temples, Hera was worshipped in association with other gods. At Sparta, Sicyon, and Argos, for example, she shared sanctuaries or cults with Apollo.[96] Hera was also sometimes connected with Hebe.[97]

Festivals and Rituals

Hera’s festivals were usually called Heraea. The Heraea at Argos, one of Hera’s major cult centers, involved a sacrificial procession outside of the city. During this procession, the priestess of Hera rode in an oxcart while young men carried the “Shield of Hera.”[98] At the end of the procession, there was a “hecatomb,” or sacrifice of one hundred bulls. Because of this, the Argive Heraea was sometimes called the Hecatombaea.

Heraea festivals were also celebrated in other cities, such as Elis, Corinth, and Samos.

On the island of Samos, a site considered sacred to Hera,[99] there was a festival of Hera called the Toneia. This festival involved a kind of scavenger hunt in which participants searched for the cult image of Hera. When it was found, it was washed clean and dressed in new clothes.[100]

A photo of the remains of the Heraeum of Samos

TomistiCC BY-SA 4.0Another important festival of Hera was the Daedala, celebrated in Plataea and a few other nearby towns. The “Lesser” Daedala were celebrated every seven years, while the “Great” Daedala occurred every sixty years.

The Daedala was a marriage ritual that honored Hera as goddess of marriage. During the ritual, wooden dolls were dressed up as brides and conveyed in a procession to a peak of Mount Cithaeron, where they were burned on a pyre.[101] This festival commemorated the myth of how Zeus managed to reconcile with Hera after one of the couple’s quarrels (see above).

Other festivals and rituals connected with Hera were observed throughout the Greek world. There were a handful of festivals associated with the “sacred marriage” of Hera and Zeus, including the Athenian Theogamia and a festival celebrated in Crete.[102]

At Olympia, where Hera was worshipped as Hera Hippia (“Hera of the Horse”), there was a festival that involved contests of girls. This festival was said to have been established by the local queen Hippodamia to commemorate her marriage to the hero Pelops.[103]

Hera’s patronage of marriage was also evident at Sparta, where mothers consecrated their daughters to Hera Aphrodite at their weddings.[104]

At Argos, the Lecherna sacrifice (or childbed sacrifice) was based on the connection between Hera and her daughter Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth.[105] Hera was honored in a similar capacity at some of her sanctuaries, where dedications to the goddess as “child-rearing” (kourotrophos) have been discovered.

In Attica, the month of Gamelion (the seventh month of the Attic calendar) was consecrated to Hera.[106]

Finally, Hera’s worship sometimes had chthonic associations—that is, associations with the earth and the Underworld. These were especially characteristic of Hera’s cult in Boeotia.

Foreign Cults

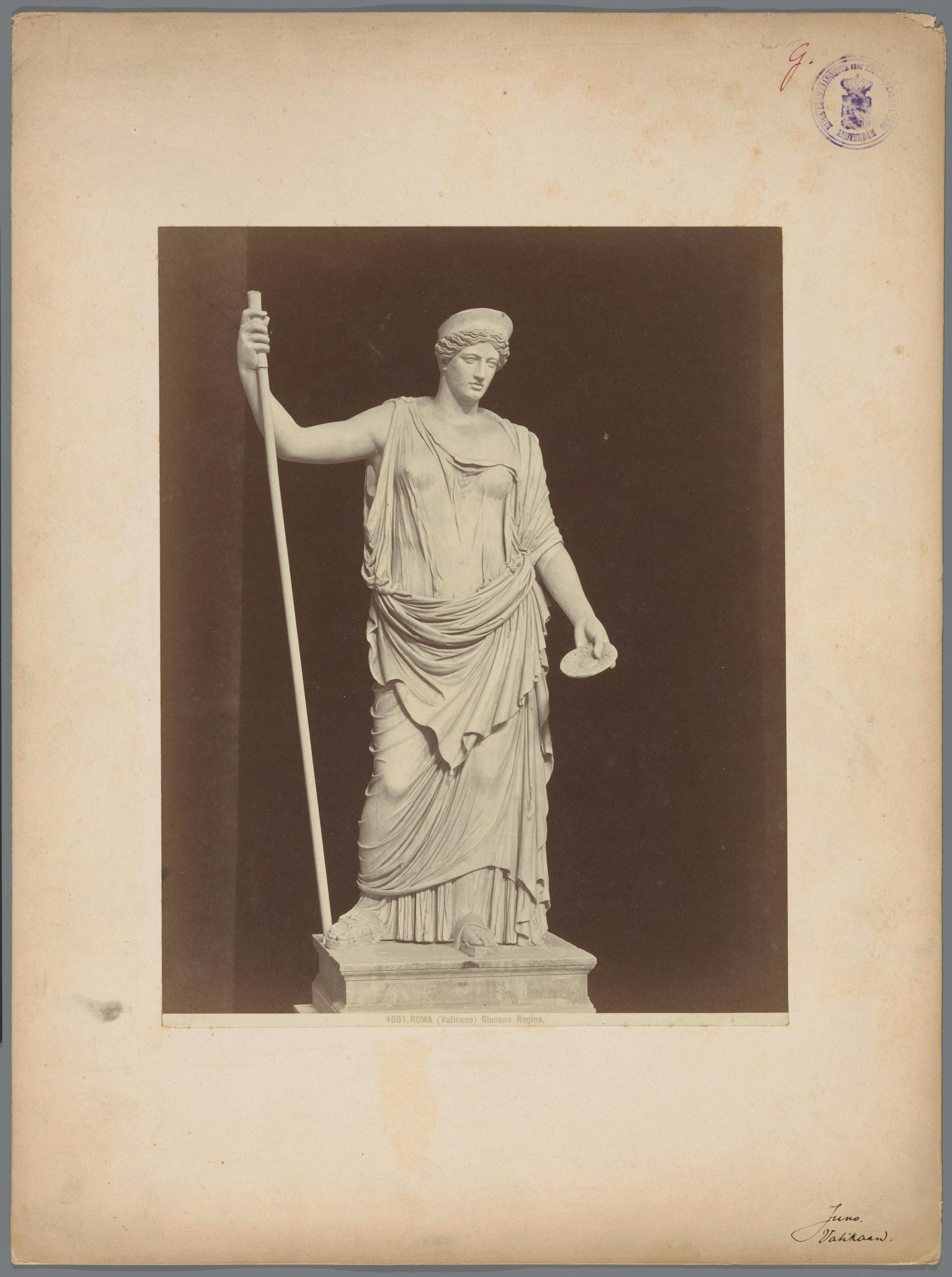

Hera was identified with the Roman goddess Juno from a very early period. Indeed, most of Juno’s mythology and iconography was adopted from the Greek Hera. Juno, like Hera, was a goddess of marriage and childbirth as well as of young men of fighting age; she was also one of the principal gods of the Roman state.

Statue of Juno Regina, photo taken between 1850 and 1900

RijksmuseumCC0In Thrace, the Balkan region stretching northeast of mainland Greece, a special cult of Hera began to form during the Roman Imperial period. This cult, which we find evidence of in literature and art, appears to have combined elements from the Greek cult of Hera and the Roman cult of Juno Regina (“Queen Juno”).[107]

Popular Culture

In contrast to better-known figures such as Zeus and Heracles, Hera has not figured prominently in popular culture. However, she does occasionally appear in modern adaptations of Greek mythology.

The Disney animated film Hercules (1997) offers an interesting twist on the relationship between Hera and Heracles (Hercules to the Romans): rather than trying to murder the boy in his crib as punishment for her husband’s infidelity, the film presents Hera as Hercules’ loving mother. She is terribly distraught when the infant is made mortal and forced to live among the humans.

In some adaptations of the Trojan War myth—including the 2003 miniseries Helen of Troy as well as the more recent 2018 miniseries Troy: Fall of a City—Hera is depicted in the famous Judgment of Paris scene.

Overall, Hera is not a well-developed character in popular representations, which may reflect some lingering confusion about her personality: though she served as the embodiment of a faithful wife and mother, she also viciously punished those who crossed her.