Demeter

Apulian red-figure hydria showing Demeter (right) with Metanira (left) by the Varrese Painter (ca. 340 BCE)

Altes Museum, Berlin / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainOverview

Demeter was one of the Twelve Olympians and the goddess of fertility and agriculture. She was also a goddess of women, family, law, and the Mysteries (secret religious rites).

One of the children of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, Demeter was the sister of Zeus, Hestia, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. Her most famous daughter was Persephone—the bride of Hades and the mistress of the Underworld.

Rarely meddling in others’ affairs, Demeter was among the most beloved and least controversial of all Greek deities. Her most important cult center was at Eleusis in Attica, though she had many sanctuaries throughout the Greek world.

Apulian red-figure hydria showing Demeter (right) with Metanira (left) by the Varrese Painter (ca. 340 BCE)

Altes Museum, Berlin / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainKey Facts What were Demeter’s attributes?

Demeter was easily recognized by her attributes of wheat (or corn), a torch, and sometimes a sickle. She was generally represented as a modestly robed woman wearing a headdress.

In art and literature, Demeter was often shown alongside her daughter Persephone, or, occasionally, with other gods such as Poseidon. Other times, Demeter was depicted with her favorite animals, especially piglets and bullocks.

Roman statue of Demeter (2nd century CE)

British Museum, London / OrangeaurochsCC BY 2.0Who were Demeter’s children?

Demeter had relatively few consorts, and thus relatively few children. The most famous of her offspring was no doubt Persephone, born from her union with Zeus. Demeter also coupled with Poseidon, the god of the sea, and gave birth to the immortal horse Arion. Finally, Demeter was the mother of Pluto (the personification of wealth) by her mortal lover Iasion.

The Return of Neptune by John Singleton Copley (ca. 1754)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainDemeter’s Search for Persephone

By far the most important myth of Demeter involved her search for her daughter Persephone, whom Hades, the god of the Underworld, had abducted to be his bride.

Demeter was devastated by her daughter’s absence—so much so that she left the crops to wither and die. To prevent a famine, Persephone was allowed to return to her mother for part of the year. But because she had tasted food during her time in the Underworld, Persephone had to spend the other part of the year with her infernal husband Hades.

During her long search for Persephone, Demeter stopped at Eleusis, a city in Attica, where she taught the local people about agriculture and her secret religious rites. It is for this reason that Eleusis became Demeter’s most important cult center and the home of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Attic red-figure bell-krater attributed to the Persephone Painter (ca. 440 BCE) showing the ascension of Persephone from the Underworld; Persephone (left) is guided by Hermes (center left) and Hecate (center right) as Demeter stands to the side (right) waiting to receive her

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainRoles and Powers

Demeter was above all the goddess of agriculture, responsible for the cultivation and harvest of grain. The ancients believed that those who did not properly honor Demeter risked starving to death. It was Demeter who, “amid the driving blasts of wind, separate[d] the grain from the chaff.”[1] It was also Demeter who made the “holy grain sound and heavy”[2] as farmers tilled their soil.

Demeter was also a goddess of women—especially married women—and was therefore invoked as a protector of women and the household. Demeter, like Artemis, presided over women’s passage from childhood to adulthood. She was sometimes even seen as a healer (especially of disorders affecting the breast or womb).

Finally, Demeter was the central goddess of many mystery cults (especially the Eleusinian Mysteries), which preached the importance of initiation and ritual in order to attain a privileged afterlife.

Sometimes Demeter was also associated with death and the infernal powers, as when she was worshipped (in Arcadia) under the title Erinys (“Fury”).

Demeter was connected with various gods who supported her in her diverse functions. Her chief companion was, of course, her daughter Perseophone (also called Kore or Despoina in certain ritual contexts). In fact, Demeter and Persephone were often invoked as a pair, as τὼ θεώ (tṑ theṓ), “the two goddesses”; τὼ θεσμοφόρω (tṑ thesmophórо̄), “the two culture bringers”; or even Δαμάτερες (Damáteres), “the Demeters.”[3] Demeter and Persephone came to be viewed as two aspects of the same agricultural cycle.

Demeter and Persephone by John D. Batten (19th or 20th century)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDemeter was also connected with Rhea, the Titan mother of the gods; Cybele, a mother goddess imported from Phrygia; and Gaia, the primordial earth goddess. In some early sources, Demeter was even conflated with Rhea or Cybele (themselves often identified as the same being in Greek mythology and religion).[4] Other traditions identified Demeter with Gaia.[5] In one source—the so-called “Derveni Papyrus”—all four goddesses seem to have been merged into one.

Demeter was associated with other gods as well, especially Dionysus, but also, more locally, with Poseidon (in Arcadia) and the mysterious Iacchus (in Eleusis). Still other gods associated with Demeter included Apollo, Artemis, Athena, Hera, the nymphs, and the Cabiri.

Attributes

Demeter’s main attributes were sheaves of wheat (or other crops, such as corn or poppies), a scepter, and a torch. She was also imagined wearing a headdress or clad in flowing robes. For transportation, Demeter possessed a flying chariot drawn by dragons.

Attic red-figure stamnos showing Demeter, Persephone, and Triptolemus by the Triptolemos Painter (ca. 480–470 BCE). Louvre, Paris.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDemeter’s sacred animals included snakes and reptiles, cranes, and her favorite sacrificial victims: piglets and bullocks. In addition to grain crops, her sacred plants included apples, pomegranates, myrtle, asphodel, and narcissus.

Iconography

In her iconography, Demeter was generally depicted as a beautiful but modest goddess. She could be distinguished by her familiar attributes of wheat and torches. Over her hair (which was the color of grain) she wore a polos (headdress), veil, or headband; she was generally dressed in a chiton (tunic), peplos (dress), or himation (robe).

Sometimes, she could also be distinguished by a kalathos (basket for storing wool), sickle, oinochoe (wine jug), or phiale (libation bowl), which she held in her hands.

In art, Demeter was commonly shown seated. She usually rested upon a throne, though some representations showed her sitting in a flying chariot, which was either equipped with wings or pulled by serpentine dragons.

In art, it was customary to depict Demeter alone, without any consort. However, the goddess was sometimes seen in the company of her daughter Persephone or with Iasion, a mythical young man from Crete who was one of her consorts.

In later periods, during the time of the Roman Empire, the abduction of Persephone became a popular subject on stone sarcophagi; in these scenes, Demeter was often shown in the background, riding her chariot and holding her torches.

Roman imperial-era sarcophagus showing the abduction of Persephone by Hades (right) as Demeter (left) searches for her lost daughter (200–225 CE)

The Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainIn Arcadia, there was an important cult of Demeter Melaina (“Black Demeter”) in which Demeter was depicted with the head of a horse (see below).[6]

Etymology

The goddess Demeter (Greek Δημήτηρ, translit. Dēmḗtēr) is attested from the earliest periods of Greek history. She appears in texts from as early as the Minoan period (ca. 1800–1450 BCE), where her name shows up in the Linear A syllabic script as da-ma-te.[7]

In the early Greek language used by the Mycenaeans and written in the Linear B script (ca. 1600–1100 BCE), da-ma-te seems to have meant something different and likely did not refer to the goddess Demeter.[8] However, this does not mean that Demeter was not worshipped by the Mycenaean Greeks: the Mycenaean si-to-po-ti-ni-ja (“mistress of the grain”) is likely a reference to Demeter in her Bronze Age guise.[9]

While the etymology of the name “Demeter” continues to be disputed, the name is more comprehensible than those of most of the other Greek gods. The second part of the name clearly originated in the Greek (and Indo-European) word matēr (Greek μήτηρ, translit. mḗtēr; Indo-European *méh₂tēr), meaning “mother.”[10]

The first part of the goddess’s name is more difficult. One suggestion—apparently already made in the Classical period[11]—is that Dē is a different form of the Greek word γῆ (gê), meaning “earth.” The name “Demeter” would in this case mean “earth mother.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Demeter Δημήτηρ Phonetic

IPA

[dih-MEE-ter] /dɪˈmi tər/

Other Names

Demeter’s name varied somewhat according to regional dialects. The name by which she is known today, Demeter, represents the Attic form Δημήτηρ (Dēmḗtēr); the goddess was Δαμάτηρ (Damátēr) in Doric and Boeotian, and Δωμάτηρ (Dōmátēr) in Aeolian. A shorter alternative to Demeter (in Attic) was Δηώ (Dēṓ).

Epithets

Demeter was invoked under many titles and epithets, including potnia (“mistress”), despoina (“mistress of the household”), thesmophoros (“bringer of law”), sito (“she of the grain”), and chthonia (“she of the earth”). Among the goddess’s other epithets were chloē (“the green one”), kallistephanos and eustephanos (“well-crowned”), semnē and hagnē (“hallowed”), and eukompos (“fair-haired”).

Attributes

Domains

Demeter was invoked under numerous titles and epithets. Many of these were cult titles (also known as epicleses) related to her various functions. Thus, as a goddess of grain and agriculture, Demeter had titles such as ἀνησιδώρα (anēsidṓra), “she who sends up sheaves”; καρποφόρος (karpophóros), “fruit-bearing”; and σιτώ (sitṓ), “she of the grain.”

As a goddess connected with earth and the subterranean realm of the dead, Demeter had titles such as ἐρινύς (erinýs), “fury”; μέλαινα (mélaina), “black”; or χαμύνη (chamýnē) and χθωνία (chthōnía), “of the earth.”

As a goddess of law and culture, her major title was θεσμοφόρος (thesmophóros), “law-bringing.”

Illustration of a relief from Pompeii showing Demeter (Ceres) with her attributes of torch, sheaves of wheat, basket of wheat, and wheat crown

Meyers Konversationlexikon (1885–1890)Public DomainOther titles of Demeter reflected specific local connections. Thus, we have Demeter Eleusinia (Ἐλευσίνια/Eleusinía), “Demeter of Eleusis”; Demeter Lernaia (Λερναῖα/Lernaîa), “Demeter of Lerna”; Demeter Mysia (Μύσια/Mýsia), “Mysian Demeter”; and so on.

Finally, Demeter had many literary epithets in the works of Homer, Hesiod, and other ancient authors. Some of these epithets addressed her divine functions, including ἄνασσα and πότνια, “mistress”; ἀγλαόδωρος (aglaódōros), “she who bestows splendid gifts”; ἀγλαόκαρπος (aglaókarpos), “she who bestows the splendid crops”; ἁγνή (hagnḗ) and σεμνή (semnḗ), “august”; and so on.

Other epithets addressed her appearance, such as εὐστέφανος (eustéphanos) and καλλιστέφανος (kallistéphanos), “well-crowned”; ἠΰκομος (ēǘkomos), “she of the beautiful hair”; ξανθή (xanthḗ), “blonde”; χλόη (chlóē), “green one”; and so on.

Finally, other epithets addressed attributes associated with Demeter, such as ξιφηφόρος (xiphēphóros), “sword-wielding”; χρυσάωρ (chrysáōr), “she of the golden sword”; and so on.[15]

Family

One of the Olympian gods, Demeter was the daughter of the Titans Cronus and Thea and the sister of Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Hera, and Hestia.[16] Demeter and her siblings managed to dethrone their Titan parents after a decade-long war, naming themselves the new rulers of the cosmos.

Though Demeter never married, she did have several children. By far the most famous of these was Persephone, her daughter by her brother Zeus.[17] In local Arcadian traditions, Demeter was also impregnated by her brother Poseidon, giving birth to a flying horse named Arion[18] and/or a fertility goddess named Despoina[19] (depending on the tradition).

Demeter also had a mortal lover named Iasion. According to this story, known from a handful of ancient sources, Demeter slept with Iasion in a thrice-plowed field, often said to have been located in Crete. The jealous Zeus promptly struck Iasion down with a thunderbolt, but Demeter was already pregnant and bore Iasion a son named Plutus (“Wealth”). In a later source, the union of Demeter and Iasion was said to have also produced Philomelus.[20]

Fragment of the "Great Eleusinian Relief" showing Demeter (left) and Persephone (right) with the young Triptolemus (center), Roman copy (ca. 27 BCE–14 CE) after a Greek original (ca. 450–425 BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, AthensPublic DomainOther traditions involving the consorts and children of Demeter were more obscure. One genealogy, for example, made Demeter the mother of the Underworld goddess Hecate (by Zeus).[21] Another tradition, likely arising from the identification of Demeter with the Egyptian goddess Isis, made Demeter the mother of Artemis.[22] In a Cretan tradition, Demeter was the mother of the local hero Eubulus, presumably by Carmanor.[23]

Yet another story told of how Demeter loved the handsome Athenian Mecon, who was transformed into the poppy.[24] And in a genealogy recorded in the sixteenth century by Natalis Comes, Demeter was the mother of the river god Acheron (by the sun god Helios).[25]

Demeter was also closely associated with the god Dionysus. Though in mainstream mythology Dionysus was the son of the Theban princess Semele, some religious groups regarded him as the son,[26] grandson,[27] or consort[28] of Demeter. This version of Dionysus was sometimes conflated with Iacchus, Demeter’s associate at the Eleusinian Mysteries.[29]

Mythology

Origins

There is some evidence to suggest that the worship of Demeter originated on the island of Crete. Demeter’s most important human consort, for example, was a Cretan hero named Iasion. There are also references to Demeter’s connection with Crete in early literature, including the second Homeric Hymn (the Hymn to Demeter).[30] Finally, there were early Mysteries of Demeter in the important Cretan city of Knossos.[31]

However, other possibilities have also been suggested for Demeter’s origins. The Greeks identified Demeter with the Egyptian goddess Isis from an early period,[32] and it is possible that certain aspects of Demeter’s cult were borrowed from the Egyptians. Others have speculated that Demeter may have originated in specific Greek regions such as Euboea or Thessaly, or even that her worship came from Thrace.

Birth and Early Years

Demeter was one of the six children of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. Cronus, who had overthrown his own father to assume control of the cosmos, feared that his children would do the same to him. Thus, he swallowed each of his offspring as soon as they were born: Hades, Hestia, Hera, Poseidon, and Demeter. Only Zeus, the youngest child, managed to escape, being brought up in secret on the island of Crete.

Pentelic marble relief showing the procession of the Twelve Gods and Goddesses (first century BCE/first century CE)

The Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainDemeter resided in her father’s belly until Zeus forced Cronus to regurgitate the children. Once freed, Demeter joined forces with Zeus and his allies in the Titanomachy, a ten-year war against the Titans. She reigned alongside the other Olympians following their victory.[33]

Demeter, Persephone, and the Eleusinian Mysteries

The mythology of Demeter was largely centered around the abduction and liberation of her daughter Persephone. It all began when Hades, the god of the Underworld, first saw the beautiful Persephone and fell in love with her. He descended upon her in his chariot and stole her away to his domain.[34]

The Fate of Persephone by Walter Crane (1877).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDevastated by the loss of her daughter, and unaware of Hades’ role in her disappearance, Demeter set off in search of the missing girl. The second Homeric Hymn, dedicated to Demeter, vividly describes the mother’s anguish as she searched for her daughter:

Bitter pain seized her heart, and she rent the covering upon her divine hair with her dear hands: her dark cloak she cast down from both her shoulders and sped, like a wild-bird, over the firm land and yielding sea, seeking her child. But no one would tell her the truth, neither god nor mortal men; and of the birds of omen none came with true news for her.[35]

As Demeter searched far and wide, she happened to visit Eleusis in the guise of an old woman. While there, she was greeted warmly and given shelter by Queen Metanira and King Celeus. One of the servants of the royal household, an old woman named Iambe, even managed to make the depressed Demeter laugh by telling her a dirty joke.[36]

In return for the kindness shown her at Eleusis, Demeter nursed the young son of Metanira and Celeus, known as Demophon in most versions of the myth.[37] Demeter took a liking to Demophon and sought to burn away his mortality in the family fireplace, effectively turning him into a god. But this plan failed when Metanira walked in on the ritual and screamed at the sight of her son in a fire—an understandable, though ultimately disastrous, response.

Demeter rebuked Metanira for her lack of understanding. In most traditions, Demophon was now doomed to die like any ordinary mortal, while in other traditions he actually died as a result of the bungled ritual.[38]

Nonetheless, Demeter ensured that Eleusis became an important center for her worship, teaching the secrets of agriculture to the Eleusinian prince Triptolemus. In the second Homeric Hymn, the goddess gives detailed instructions to the Eleusinians for the construction of a great temple in her honor.[39]

Meanwhile, Demeter discovered what had happened to Persephone. In the best-known tradition, the goddess Hecate directed Demeter to Helios, the god of the sun, who alone had witnessed the abduction; it was Helios who finally told Demeter where to find her daughter.[40]

In other traditions, however, Demeter learned of her daughter’s whereabouts from some other source, such as the nymph Arethusa[41] or the people of Hermione.[42] In some accounts, Demeter had help from other gods, too, such as Athena[43] or Artemis.[44]

Demeter Mourning Persephone by Evelyn De Morgan (1906)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainWhen she learned that her daughter had been abducted by the grim god of the dead, Demeter became bitter and withdrawn, refusing to eat or drink. Her enormous despair caused the rains to stop and the crops to die in the fields.

The other Olympians soon realized that they needed to ease Demeter’s sorrow before the drought endangered human life. To deal with this situation, Zeus sent Hermes to the Underworld to order Persephone’s return. Another god, Hesperus (the personification of the evening), soothed Demeter and convinced her to break her fast.[45]

Though Hades was initially unwilling to release Persephone, he ultimately agreed to do so—provided Persephone had not eaten anything in the Underworld. Unfortunately, Persephone had eaten a few pomegranate seeds and was therefore forced to return to the Underworld annually for either one-third or one-half of the year (depending on the version of the tale being told).[46]

In some accounts, Persephone’s Underworld meal was betrayed by Ascalaphus, the son of the River Acheron. To punish him, Demeter turned him into an owl.[47]

The Return of Persephone by Frederic Leighton (1891).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe seasonality of Persephone’s absence from and return to Demeter became central to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Even in antiquity, the myth was sometimes interpreted as an allegory for grain cultivation, in which the seed is hidden in the Underworld (like Persephone) before emerging in its proper season. The myth was thus thought to symbolize the cycles of life and death that were integral not only to agriculture but to all life.

The Loves of Demeter

Demeter was never represented as a particularly amorous or promiscuous goddess. She did, however, have a few important lovers and consorts, immortal as well as mortal.

In Book 14 of Homer’s Iliad, Zeus names Demeter as one of his many lovers.[48] He does not name any children born from their union, but in most traditions, Persephone was the daughter of Demeter and Zeus.

Demeter’s most important mortal consort was a man named Iasion. Demeter and Iasion slept together in a “thrice-ploughed fallow in the rich land of Crete.”[49] But Zeus, resenting that a goddess should be loved by a mere mortal, killed Iasion soon after with a thunderbolt.[50] In an alternative tradition, Iasion was killed by Zeus because he tried to rape Demeter[51] or because he violated her cult image.[52]

In a later account, Demeter bore Iasion two sons: Pluto and Philomelus. The brothers subsequently quarreled because the rich Pluto (whose name means “wealth”) refused to share his money. Forced to fend for himself, Philomelus invented the plow to till his fields—a tool that naturally impressed the agrarian goddess Demeter. She placed Philomelus in the sky after his death as the constellation Bootes.[53]

In Arcadia, Demeter was often paired with her brother Poseidon. In one myth, told at the Arcadian city of Thelpusa, Poseidon pursued Demeter while she was searching for her lost daughter Persephone, hoping to sleep with her. Wishing to avoid Poseidon’s advances, Demeter turned herself into a mare and grazed among the other horses outside Thelpusa.

Not to be deterred, Poseidon turned himself into a stallion and forced himself on Demeter. Since both of them were in horse form, the product of their union was the winged horse Arion.

Afterwards, it was said that Demeter was worshipped in the region with the title Erinys (“Fury”) because she was furious at Poseidon for his treatment of her. She was also worshipped with the title Lousia (“Washing”) because she had washed in the nearby Ladon River after the episode.[54]

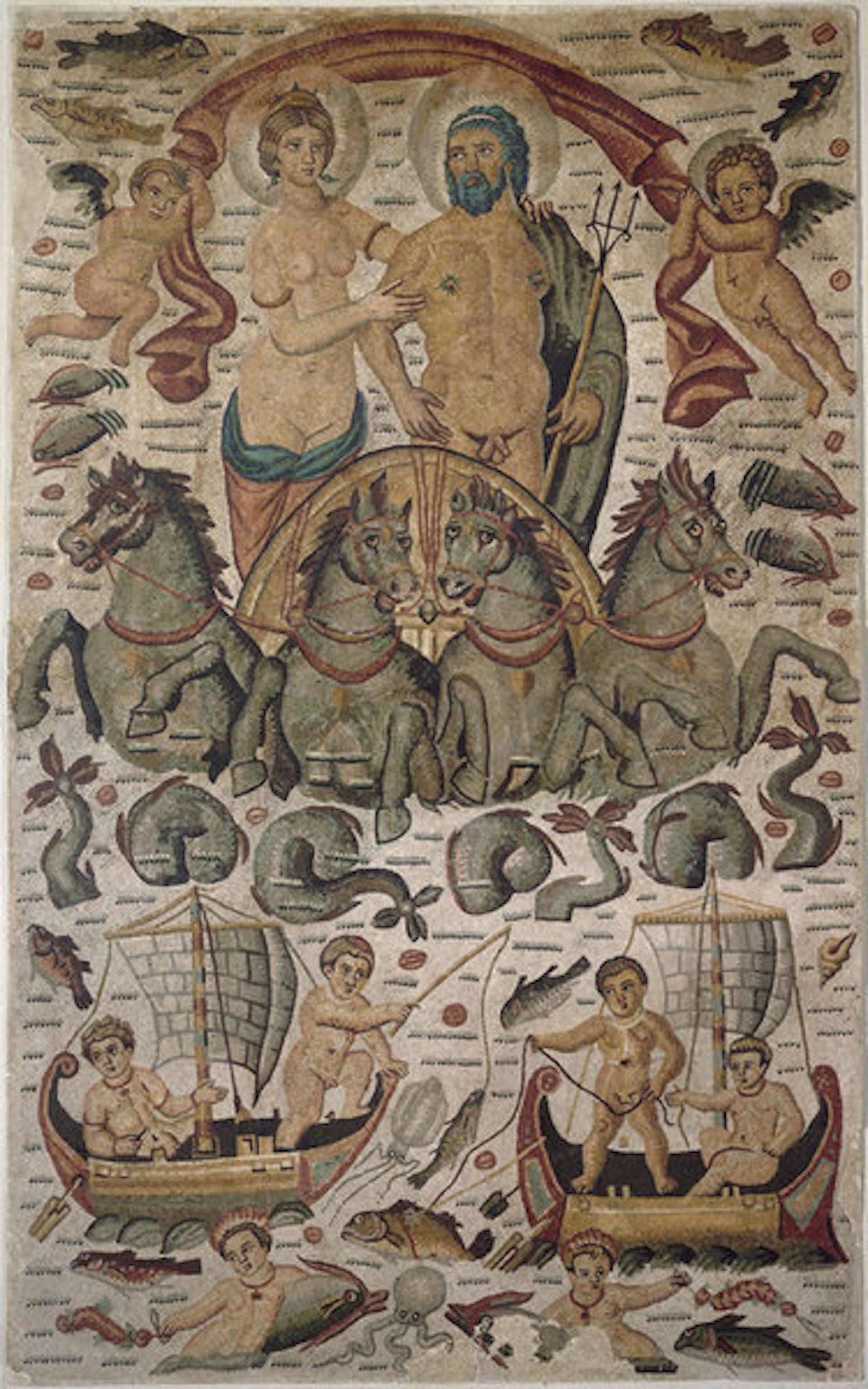

Mosaic from Cirta, a Roman settlement in North Africa (ca. 315–325 CE)

Louvre Museum, Paris, FrancePublic DomainIn Phigalia, another Arcadian city, a different story was told about the union of Demeter and Poseidon. The Phigalians said that Demeter (whom they represented in cult with a horse’s head) and Poseidon were the parents of the local goddess Despoina, the “Mistress” (likely a local version of Persephone).[55]

Demeter as Benefactor

As the goddess of grain and agriculture, Demeter was presented in many myths as a benefactor of humanity, spreading her important knowledge and rites across the world.

Demeter’s best-known mortal protégé was Triptolemus, a hero and prince from Eleusis. Though only mentioned in passing in the second Homeric Hymn, Triptolemus played a key role in many other sources for the mythology of Demeter.

In some accounts, for example, Triptolemus was front and center during Demeter’s stay at Eleusis; some even cited him as the child who was nursed and nearly immortalized by the goddess.[56] In Orphic accounts, it was actually Triptolemus (together with Eubuleu) who told Demeter what had happened to Persephone.[57]

Whatever Triptolemus’ role at Eleusis, it was usually said that Demeter taught him agriculture and sent him to disseminate this knowledge across the world. She even gave him a magical flying chariot drawn by dragons to carry him on his journey.[58]

Attic red-figure cup by the Aberdeen Painter (ca. 470–460 BCE) showing Demeter (right) with Triptolemus (left)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainDemeter continued to support Triptolemus during his travels. In one myth, the Scythian king Lyncus tried to murder Triptolemus in his sleep so that he could assume the role of bestower of grain; but Demeter intervened and changed Lyncus into a lynx before he could do so.[59]

In another myth, also set in Scythia, King Charnabon of the Getae tried to capture Triptolemus, killing one of his dragons to prevent him from escaping. But Demeter again came to the rescue, bringing Triptolemus a new chariot with a new dragon and killing Charnabon (who was afterwards placed in the sky as the constellation Ophiouchos, the “Serpent-Holder”).[60]

Triptolemus was also beset by rivals within the borders of Greece. At Patrae in Achaea, Triptolemus’ dragon chariot was stolen by Antheias, the son of his companion Eumelus. However, because Antheias was not properly acclimated to the special vehicle, he fell to his death. Triptolemus and Eumelus later founded the city of Antheia in the young man’s honor.[61]

There were other myths about Demeter as a benefactor as well. For example, Demeter was said to have nursed the Boeotian hero Trophonius, much as she nursed the Eleusinian hero Demophon.[62]

In Athenian myth, Demeter inducted several heroes into her Mysteries at Eleusis. Heracles, for example, was initiated into the Mysteries in preparation for his journey to the Underworld (which was required for his final labor). But since the Eleusinian Mysteries were traditionally open only to citizens of Attica, Heracles first needed to be adopted by a local man named Pylius.

Another obstacle came from the fact that Heracles was still ritually polluted from having murdered the Centaurs. To purify him, Demeter founded the Lesser Mysteries, religious rites that dealt with such matters.[63] Later, the Dioscuri (Castor and Polydeuces) were initiated into the Mysteries as well, being adopted by a local man named Aphidnus (just as Heracles had been adopted by Pylius).[64]

Demeter as Punisher

Like any Greek deity, Demeter could be as vengeful as she was generous. Probably the most famous example of Demeter’s wrath is the myth of Erysichthon.

In Callimachus’ detailed retelling, Erysichthon was a rich king in Thessaly who foolishly went to a sacred grove to cut down trees for a banquet hall. Demeter, disguising herself as her own priestess Nicippe, approached Erysichthon to warn him that he should abandon his impious plan.

But Erysichthon only made matters worse for himself when he threatened the disguised goddess with his ax. As punishment, Demeter cursed Erysichthon with unrelenting hunger. The insatiable Erysichthon quickly burned through all his wealth in a doomed attempt to satisfy his hunger, until at last he wasted away.[65]

The Woodcutter and the Hamadryad Aigeiros by Émile Bin (1870)

Musée Thomas-Henry, ManchePublic DomainOther versions of the myth are more complicated, with Erysichthon repeatedly selling his shape-shifting daughter Mestra in order to buy food. Every time Erysichthon sold Mestra, she would transform herself and find a way to return to her father so that he could sell her again. Eventually, however, this plan failed, and Erysichthon ended up eating himself.[66]

In a slightly less troubling alternative, Erysichthon’s behavior angered the locals, and he was forced to leave Thessaly and settle in Anatolia, where he founded Cnidos.[67]

A similar story was told about the Thessalian king Triopas (sometimes said to have been Erysichthon’s father or brother),[68] and about a son of Helios named Aethon.[69]

Other Myths

There are a handful of other myths about Demeter.

In one tradition, which connected Demeter with the origin of mint, the goddess was angered by a nymph named Minthe, who boasted that she was even more beautiful than Persephone. Seeking to avenge her daughter’s pride, Demeter trampled Minthe beneath her feet, turning her into the mint plant.[70]

In another myth, Demeter unknowingly ate the shoulder of Pelops when the boy’s father, Tantalus, served him to the gods at a feast.[71] Some sources added that after Pelops was restored to life and Tantalus punished for his wickedness, Demeter fashioned a new shoulder for the boy out of ivory.[72] Later authors embellished the myth by adding that Demeter did not notice what she was doing because she was distracted by the loss of Persephone.[73]

Terracotta plaque with Pelops and Hippodamia, Roman (270 BCE–68 CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAnother strange myth, known from very early sources, told of how a snake called Cychreides traveled from Salamis to Eleusis. There, at the site of the Mysteries, the snake became Demeter’s attendant.[74]

In literature, Demeter did not feature in as many myths as some of the other gods. But in art, she was sometimes shown as a participant in additional mythical scenes, such as the lavish wedding of Peleus and Thetis, the birth of Athena, or the liberation of Prometheus. As one of the Olympians, she was often shown fighting against the Giants in artistic depictions of the Gigantomachy.

Alternative Mythologies

Some Greek authors and religious groups crafted very different versions of Demeter and her mythology. One notable example comes from the fragmentary texts of the Orphics, a Greek religious community that professed to follow the teachings of the mythical musician Orpheus.

Orpheus and Eurydice by Auguste Rodin (modeled ca. 1887, carved 1893)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Orphics seem to have identified Demeter with Rhea, one of the Titans and the wife of Cronus. This Demeter/Rhea had sex with her son Zeus, and from their union was born Persephone (whom the Orphics seem to have imagined with two faces and horns). Zeus then had sex with his daughter Persephone, and from her was born the Orphic Dionysus, who was sadly torn apart and eaten by the violent Titans.[75]

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

Temples of Demeter were usually called Megara (from the Bronze Age Greek word megaron, meaning “great hall”) and were often built in groves.[76] Men were completely excluded from many of Demeter’s sanctuaries; there was even a story that the Athenian general Miltiades suffered a fatal injury when he broke into a sanctuary of Demeter on Delos—punishment for treading on forbidden ground.[77]

Demeter’s sanctuary at Eleusis, called the Telesterion, was possibly the most important sanctuary of Demeter in the Greek world; it was here that the Eleusinian Mysteries were based. The Telesterion was very old, dating back to at least the seventh century BCE. Demeter shared the sanctuary with Kore (Persephone) and Iacchus.

Demeter also had a few important sanctuaries in the region of Arcadia, where she was characteristically worshipped in connection with Poseidon. At Thelpusa, for example, there was a sanctuary where she was worshipped as Demeter Erinys (“Demeter the Fury”).[78]

At Phigalia, she was worshipped as Demeter Melaina (“Black Demeter”) and was regarded as the mother (by Poseidon) of the major local goddess Despoina (“Mistress”).[79] At Lycosura, similarly, Demeter was connected with Despoina, and was even subordinate to her.[80] Meanwhile, at Phineus, Demeter was represented as the masked Demeter Kidaris (“Headdress Demeter”) and was honored accordingly by a ritually masked priest.[81]

Photo of the Temple of Despoina in Lycosura, Greece

ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0Demeter had other sanctuaries and cults scattered throughout the Greek world. In Thebes, the main city of Boeotia, she had a sanctuary in a building said to have once been the home of Cadmus, the city’s founder.[82] In Thessaly, we find references to very early sanctuaries at Pyrasos,[83] Antron,[84] and Anthela.[85] At Olympia, Demeter was worshipped in connection with the earth, as Demeter Chamyne.[86] In Sparta and Hermione, similarly, she was Demeter Chthonia, “Demeter of the Earth.”[87]

Festivals and Rituals

The festivals of Demeter were (perhaps unsurprisingly) primarily the domain of women. Often, men were strictly prohibited from participating in or even knowing about the festivals of the goddess.

One of the most important festivals of Demeter, the Thesmophoria, was celebrated only by adult women; men were not permitted to attend. The Thesmophoria was held annually in Athens and in many other Greek cities; it was usually connected with the sowing of the fields in late autumn, though sometimes it was pinned to the spring harvest instead.

The Thesmophoria was a festival of rupture, where everyday conventions were temporarily abolished. In some cities, the festival featured fasting, obscenities, and the shunning of men.[88]

In Athens, the festival was celebrated over three days, between the eleventh and thirteenth of the month of Pyanopsion (corresponding to October/November). In some cities, it lasted even longer.

On the first day, known as the anodos (“ascent”), the women came on foot to the Acropolis, where they stayed during all three days of the festival, sleeping on beds of twigs. The second day, known as the nesteia, was a day of fasting, commemorating Demeter’s fast as she searched for Persephone. The third day, the kalligeneia (“fine birth”), featured sacrifices to ensure the prosperity and propagation of the citizenry.

One of the central events of the festival took place on the first night. A procession would travel to a site where an underground pit (called a megara) was dug. Offerings called thesmoi (hence the name of the festival) were put inside, including young piglets, and the remains of last year’s offerings were removed.

Another important festival of Demeter was the Eleusinia, held every two years around the end of the summer. This festival honored Demeter and her daughter Persephone (often called Kore, or “Maiden,” in ritual contexts); it was a kind of thanksgiving for the goddess’s gift of grain to humanity. The festivities included games and contests.

Possibly the most famous festival of Demeter, however, was the Eleusinian Mysteries (unrelated to the Eleusinia festival). As the name suggests, much of what happened during the Eleusinian Mysteries remains shrouded in mystery. Those who participated in the rituals of this cult (held at a Panhellenic sanctuary in Eleusis, in the region of Attica) were sworn to secrecy; this vow was clearly taken seriously throughout the existence of the cult, since almost no details of the mysteries are known today.

A view of the excavation of Eleusis, Greece. This is the site of the annual Eleusinian Mysteries and an early temple to Demeter and Persephone, built around the 7th century BCE.

Marcus CyronCC BY-SA 2.0The Eleusinian Mysteries (also called the “Greater” Mysteries) were celebrated in the autumn month of Boedromion, following the “Lesser” Mysteries held at Agrae in the spring month of Anthesterion. At the heart of the Eleusinian Mysteries were Demeter and her daughter Persephone (also called Kore or “Maiden”).

The central theme of the cult’s rituals appears to have been the anodos, or “ascent,” of Persephone from the Underworld to the world of the living. The cult thus emphasized the constant renewal of life, itself symbolized by the various cycles of nature over which Demeter presided: the seasons, birth and death, and so on. Initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries—which was open to all genders and social classes—promised a blessed afterlife.

There were other agrarian festivals celebrated in honor of Demeter, too. These included the Haloa, the Proerosia, the Kalamaia, and the Thalysia, among others.

Demeter, like the other Greek gods, received sacrifices in both public and private cult. These sacrifices included animals such as pigs (symbolizing fertility), bulls, and cows, but also prepared foods such as honey cakes and fruits. At Sparta and Hermione, a pregnant cow would be killed by elderly women and offered as a sacrifice to Demeter.[89]

Other rituals connected with Demeter were more unusual. At Demeter’s sanctuary at Patras, for example, a mirror was used as an oracle for the sick.[90] At another sanctuary of Demeter, in Basilis, the goddess was honored with a female beauty contest.[91]

Popular Culture

Demeter’s pop culture presence is limited. When she does appear in modern adaptations of Greek mythology—in films such as Clash of the Titans (1981) and Hercules (1997), for example—she is often merely ornamental.

Though Demeter may lack the allure of some of her more powerful male counterparts, such as Zeus and Poseidon, her image and aura have persisted in association with agriculture. Demeter International, for example, is the name of the largest certification organization for biodynamic farming, a type of farming with exacting standards of “purity.”

There is also a Demeter Fragrance Library—a company that offers cosmetics designed to smell like flowers, herbs, and other agricultural elements, including “Tomato,” “Grass,” and “Dirt.”