Jason

Medea Rejuvenating Aeson by Corrado Giaguinto (ca. 1760)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Jason, son of Aeson, was a hero from Iolcus in Thessaly and a member of the royal family. He was best known for leading the Argonauts in their quest to steal the Golden Fleece from Aeetes, the king of Colchis.

Jason married Medea, a powerful witch and the daughter of Aeetes; she betrayed her own father to help Jason retrieve the Golden Fleece. When Jason abandoned Medea, however, she took a terrible revenge on him, murdering both his bride-to-be and her own children. A one-time hero, Jason died broken and forgotten.

Key Facts Who were Jason’s parents?

Jason was the son of Aeson, a member of the royal family of Iolcus, and Aeson’s wife (whose name varies widely depending on the source). In one tradition, Aeson was the rightful king of Iolcus and was overthrown by his brother Pelias. But in the more common tradition, Pelias was the legitimate ruler.

While Jason went in search of the Golden Fleece, Aeson remained in Iolcus. There are different stories about his ultimate fate. In some, Pelias took advantage of Jason’s absence to kill Aeson, while in others the witch Medea rejuvenated Aeson when Jason brought her back to Greece.

Medea Rejuvenating Aeson by Corrado Giaguinto (ca. 1760)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhat were Jason’s attributes?

Jason was usually imagined as a handsome young man. In literature and art, he was often shown in a panther or leopard skin, wearing only one sandal (the story of how he lost the other sandal is an important part of his myth).

Jason was best known, however, as the captain of the Argo, the ship in which the heroic Argonauts sailed to Colchis to steal the Golden Fleece. Beyond this, Jason did not have many distinguishing attributes or characteristics. He was brave and strong, but did not have the superhuman strength or speed boasted by more impressive heroes such as Heracles or Achilles.

Attic red-figure column-krater attributed to the Orchard Painter (ca. 470–460 BCE) showing Jason about to steal the Golden Fleece (left) as Athena stands by (center)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhom did Jason marry?

Jason married the witch Medea, daughter of the Colchian king Aeetes. When Jason first arrived in Colchis with the Argonauts, Medea fell in love with him and decided to help him retrieve the Golden Fleece. When the Argonauts were ready to return to Greece, Medea came with them and became Jason’s wife.

After the famous adventures of the Argonauts, however, Jason’s life soon fell apart. He was banished from his homeland due to Medea’s brutal murder of his uncle Pelias. Later, when Jason tried to abandon Medea and remarry, she punished his faithlessness by murdering his new wife as well as the children she herself had borne to Jason.

Jason and Medea by John William Waterhouse (1907)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainJason and the Golden Fleece

Jason was known primarily for his theft of the Golden Fleece. He was commanded to complete this task by Pelias, his uncle and the king of Iolcus, who was hoping to get rid of Jason so that he would not try to seize power.

The Golden Fleece was in the possession of Aeetes, ruler of the faraway kingdom of Colchis. Thus, Jason assembled a team of heroes to sail with him to Colchis on a ship called the Argo (the name “Argonauts” is derived from this ship).

In Colchis, Jason managed to steal the Golden Fleece with the help of Medea, Aeetes’ daughter, who had fallen desperately in love with him. He and the Argonauts only narrowly escaped from Colchis, dodging Aeetes’ pursuit and eventually reaching Greece after many thrilling adventures.

Jason and the Dragon by Salvator Rosa (1663-1664)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEtymology

The name “Jason” (Greek Ἰάσων, translit. Iásōn) may be related to the Greek verb ἰάομαι (iáomai), meaning “to heal.”[1]

English

Greek

Jason Ἰάσων Phonetic

IPA

[JAY] + [SUHN] [iˈason]

Titles and Epithets

Jason was sometimes known by conventional heroic epithets such as ἀρήιος (arḗios), “warlike.” But some of his more distinctive epithets, such as ἀμήχανος (amḗchanos), “hapless,” are more surprising and highlight the fact that Jason was frequently viewed as a kind of antihero in antiquity.

Alternate Names

Jason’s name occasionally appears in other forms, such as Ἰήσων (Iḗsōn) and Ἱάσων (Hiásōn). According to one obscure tradition, Jason’s name was originally Diomedes.[2]

Attributes

Locales and Kingdoms

Jason was a hero from Thessaly, a mountainous region in northern Greece. He was a member of the royal family of the city of Iolcus, located near the coast. In some traditions, Jason was the rightful heir to the throne, though in most accounts he never became a king. In only a handful of traditions was he ever named as the ruler of Iolcus or Corinth.

Appearance and Personal Qualities

Though Jason was one of the most important heroes of Greek mythology, representations of him changed considerably throughout antiquity. In the earliest sources, he was a typical hero—strong, brave, and handsome. Pindar painted him as

an awesome man armed with two spears. He wore two different types of clothing: his native Magnesian dress fitted to his marvellous limbs, and a leopard-skin wrapped around him protected him from shivering showers. His splendid locks of hair had not been cut away, but flowed shining down his back.[3]

Indeed, Pindar described Jason as almost godlike in appearance, comparing him to Ares and Apollo.[4]

Other ancient sources, however, preferred to highlight Jason’s negative qualities. Euripides, for example, represented Jason as a treacherous and opportunistic man who felt no scruples about breaking oaths or betraying his marriage.[5]

But it was Apollonius of Rhodes, a poet from the third century BCE, who gave us the most familiar representation of Jason. Apollonius’ Jason is more of an antihero, not particularly impressive as a warrior. He is repeatedly described as ἀμήχανος (amḗchanos), “hapless,” and his most important talents are his charm (especially with women), his intelligence, and his treachery.[6]

Iconography

In ancient art, Jason had no attributes that clearly set him apart from other heroes. He was often shown nude or simply dressed, wearing a tunic and traveler’s hat. By the middle of the fifth century BCE, he was almost always represented as beardless (before then, he had been shown bearded).

Despite this lack of attributes, Jason was fairly popular in Greek, Roman, and Etruscan art. He was depicted in scenes from various myths, including the voyage of the Argonauts, the theft of the Golden Fleece, the Calydonian Boar Hunt, and the funeral games of Pelias.[7]

Family

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

Jason and his myth are closely connected with the goddess Hera, Jason’s patron. The mythical Jason may have even originated as a champion of the old cult of Hera (long established in the interior of northern Greece), serving as an opponent to Pelias, who represented the newer cult of the sea god Poseidon.[31]

There are very few myths about Jason’s early life and upbringing. According to Pindar, Jason’s uncle Pelias had stolen the throne from Jason’s father Aeson; Jason was born soon after this coup. Fearing that Pelias would harm his newborn son, Aeson pretended that the boy had died and made a show of mourning for him.

But under cover of night, he secretly brought Jason to the wise centaur Chiron to be raised in the mountains, away from the city and Pelias.[32]

Pelias, meanwhile, ruled in Iolcus. Most sources (other than Pindar) made Pelius the rightful king, rather than a usurper; nonetheless, he was a cruel leader and an enemy of the goddess Hera, whose worship he neglected. Pelias was paranoid about his power, especially after an oracle warned him to beware a man wearing only one sandal.

When Jason reached adulthood, he set out for the city of Iolcus to take part in the festival of Poseidon. During his journey, he came upon a river, where an old woman (actually Hera in disguise) asked him to help her make the crossing. Jason took the old woman on his shoulders and carried her across the river, but in the process he lost one of his sandals to the rushing stream. He thus entered Iolcus wearing only one sandal.

King Pelias notices Jason and his missing sandal in this fresco from Pompeii, now at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Marie Lan-NguyenPublic DomainAs soon as Pelias saw that Jason was missing a sandal, he remembered the prophecy and feared that his nephew would take away his throne. Wanting to be rid of Jason once and for all, he sent him on what he thought to be an impossible mission: to sail to Colchis and retrieve the Golden Fleece from King Aeetes.[33] Jason, hungry for fame and glory, accepted the challenge.[34]

The Argo and the Argonauts

To get to the Golden Fleece, Jason had to make the long and dangerous sea journey to Colchis, on the far side of the Black Sea. Jason knew that he would need a good ship and a brave crew. With Athena’s help, the shipbuilder Argus created Jason’s famous vessel, the Argo, named after its builder. It was the greatest ship of Greek mythology.

Jason then set out to put together his crew, bringing together some of the mightiest heroes of his time. The so-called “Argonauts”—named for their ship—included Heracles, the twins Castor and Pollux (also called the Dioscuri), the Calydonian hero Meleager, the divine musician Orpheus, Peleus (the father of Achilles), and Peleus’ brother Telamon. According to some sources, the Arcadian heroine Atalanta was also among the Argonauts.[35]

The Outward Voyage

Though Jason was usually named as the captain of the Argo, he was only one among many heroes on the ship—and not even the most impressive hero at that. Of the Argonauts’ many adventures, Jason played an important role in only a few.

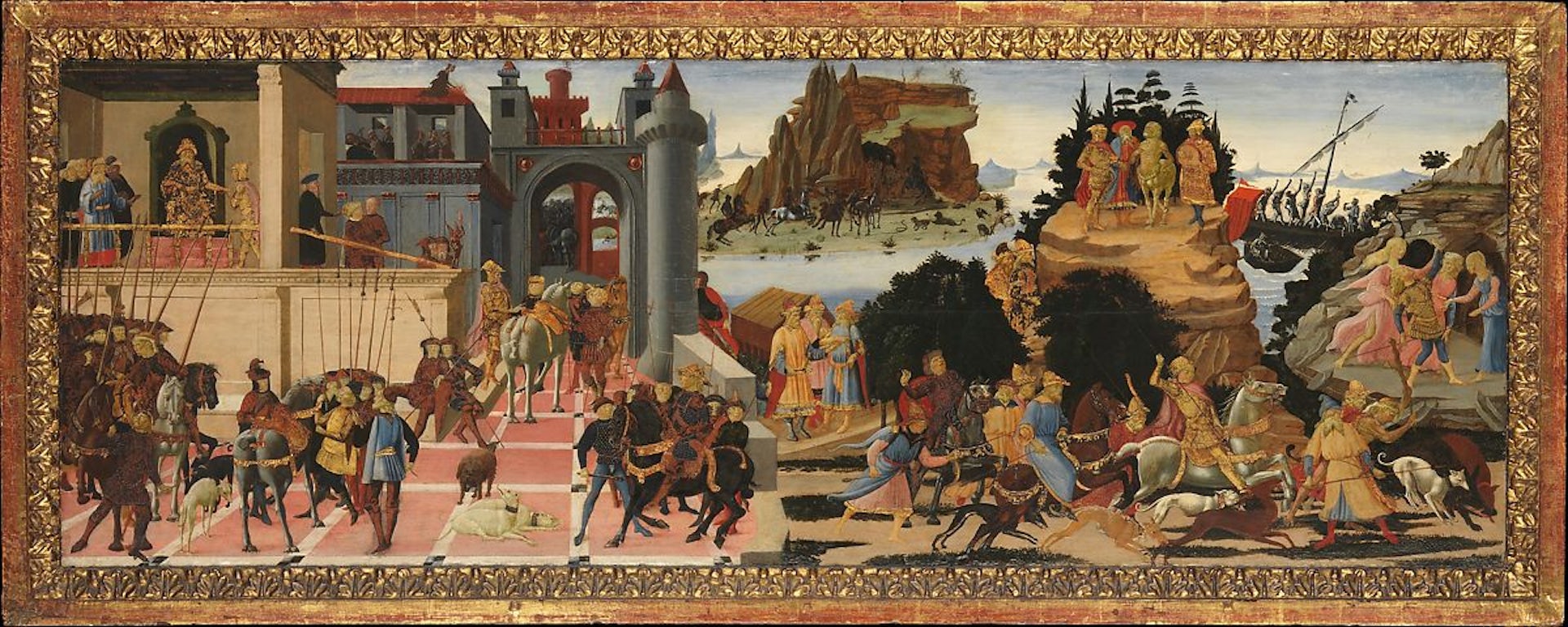

Scenes from the Story of the Argonauts by Jacopo del Sellaio (c. 1465).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn most traditions, one of the Argonauts’ first stops was on the island of Lemnos (off the coast of modern Turkey). There they encountered a society of women who, unbeknownst to them, had all killed their husbands, jealous that they preferred to sleep with their concubines. Hypsipyle, daughter of the old king, had been made their queen.

When the Argonauts arrived, the women of Lemnos eagerly took them as their lovers. Jason himself became the lover of Hypsipyle, with whom he had a few sons.[36]

Jason also played an important part in the Argonauts’ adventures among the Dolionians, a tribe living on the coast of the Sea of Marmara. Cyzicus, the king of the Dolionians, received Jason and the Argonauts and entertained them generously; in some traditions, the Argonauts even lent him military aid in a war he was fighting.

Eventually, the Argonauts continued on their journey. But shortly after leaving the Dolionians, they were driven back by adverse winds. The Dolionians, not recognizing their former guests in the darkness, attacked the ship, leading to casualties on both sides.

Jason fought Cyzicus in battle, not realizing whom he was facing, and killed him. Upon discovering their mistake, the fighting ceased, the dead were buried, and Jason and the Argonauts sailed away with heavy hearts.[37]

The Argonauts made several further stops on their voyage to Colchis, but most of these adventures spotlighted heroes other than Jason.

In Mysia, Heracles’ lover and attendant Hylas was snatched away by nymphs; while Heracles was looking for him in the woods, the Argonauts sailed away without him.[38] In the land of the Bebrycians, another Argonaut, Pollux, defeated the savage king Amycus in a boxing match.[39] And in Thrace, the Argonauts Calais and Zetes saved Phineus from the Harpies who had been tormenting him.[40]

Vase painting of Calais and Zetes rescuing Phineus from the Harpies by the Leningrad Painter (c. 460 BCE), Louvre.

Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainTowards the end of their outward journey, Jason and the Argonauts faced the Symplegades, or “Clashing Rocks”—two huge cliffs that would come together and crush anything that passed between them. Following instructions that Phineus had given them as thanks for their help against the Harpies (and, in some traditions, with additional assistance from Hera or Athena), the Argonauts managed to sail through these terrifying cliffs (mostly) unscathed.[41]

The Argonauts made a few more stops (the details of which which vary depending on the source). During one of these stops, on the island of Ares, they battled vicious birds and found the four sons of Phrixus, who had been shipwrecked while sailing from Colchis to Greece. Jason explained his mission to them and convinced the sons of Phrixus to accompany him to Colchis.[42]

Colchis

When the Argonauts finally reached Colchis, Jason went to see King Aeetes to ask for the Golden Fleece. Aeetes promised to let Jason have the fleece, but only if he completed a number of (seemingly impossible) tasks.

In the standard tradition, these tasks involved yoking a pair of fire-breathing bulls and using them to plow a field with dragon’s teeth.[43] In one tradition, Jason was also tasked with assisting Aeetes in his war against his brother Perses.[44]

Aeetes was confident that Jason would never survive the tasks. But Medea, Aeetes’ daughter and a powerful witch, fell in love with Jason (possibly due to Hera’s intervention). Medea promised to help the hero if he agreed to take her home with him and make her his wife.

When Jason consented, Medea gave him an ointment that would prevent the bulls’ fire from harming him and explained to him how he could accomplish Aeetes’ tasks. With the ointment smeared on his body and Medea’s instructions taken to heart, Jason yoked the terrible bulls:

Jason threw off his saffron cloak and, trusting in the god, set his hand to the task. The fire did not touch him; he followed the advice of the foreign woman who knew every kind of remedy. He grasped the plough, and bound the necks of the oxen in the irresistible harness, and prodding their strong-ribbed bulk with the unceasing goad the powerful man accomplished the allotted measure of his task. And Aeetes wailed, though his cry was silent, amazed at Jason’s strength.[45]

Once Jason had sown the dragon’s teeth, an army of warriors sprouted from the earth. But before they could attack, Jason threw a stone into their midst. Not knowing where the stone had come from, the warriors began fighting each other. Taking advantage of the confusion, Jason leapt into the fray and attacked the earth-born warriors until they were all dead.

Although Jason successfully completed his tasks, Aeetes reneged on his promise and refused to hand over the Golden Fleece. Thus, at nightfall Medea took Jason to the grove where the Golden Fleece was kept, guarded by a giant serpent who never slept.

In one tradition, Jason slew the serpent,[46] though in most accounts Medea simply put it to sleep using drugs.[47] But there also seems to have been one version of the myth—attested only in the visual arts—in which Jason allowed himself to be swallowed by the snake, attacked its vulnerable innards, and then climbed out through its great jaw.[48]

With the Golden Fleece in their possession, Jason and Medea joined the rest of the Argonauts, and together they sailed away from Colchis.[49]

The Return Voyage

As the Argonauts were fleeing Colchis, Aeetes sent men to pursue them. But Medea was able to slow them down by murdering Aeetes’ son (and her brother) Apsyrtus.

In one version, she and Jason lured Apsyrtus onto a secluded island and ambushed him.[50] In another version, Medea had brought the young Apsyrtus with her when she left Colchis; seeing the Colchians in pursuit, she killed him, cut him up, and threw the pieces into the sea. When the Colchians stopped to collect the pieces, the Argonauts were able to make their getaway.[51]

The Golden Fleece by Herbert James Draper (1904).

Bradford Museums and GalleriesCC BY-NC-ND 2.0Zeus was greatly angered by the vicious murder of Apsyrtus. Speaking through the bow of the Argo, he commanded Jason and Medea to be purified of their crime by Circe. He warned them that the Argonauts would never reach home if they did not do as he commanded.[52]

Having no choice but to obey Zeus, the Argonauts sailed to Circe’s island on the western coast of Italy. Circe was a daughter of Helios and the sister of Aeetes, which made her Medea’s aunt. Like Medea, she was a powerful witch. After Circe had purified Jason and Medea, the Argonauts sailed past the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, and the Planctae before reaching Scheria, the island of the Phaeacians.[53]

At Scheria, the Colchians caught up with the Argonauts. They demanded that Alcinous, the king of Scheria, return Medea to them. Alcinous said that he would do as they asked, but only if Medea and Jason were not yet married. When Arete, Alcinous’ wife, learned of this, she sent a secret message to Jason informing him of her husband’s decision.

Not wasting any time, Jason and Medea held an impromptu wedding (though in some traditions they were already married by this point).[54] Alcinous kept his word: because Jason and Medea were married, he refused to turn Medea over to the Colchians, and the Argonauts were able to leave the island.[55]

The Argonauts made a few further detours after leaving Scheria. They were shipwrecked for many days in Libya and had to face the bronze giant Talos as they sailed by Crete.[56] But at last they reached Iolcus in triumph, the Golden Fleece in their possession.

Return to Iolcus

When the Argo arrived back in Iolcus, Jason handed over the Golden Fleece and dedicated his ship to one of the gods (Hera, in most accounts). But he also wished to punish the cruel Pelias for sending him on the voyage to begin with. He therefore asked Medea to help him kill his uncle.

In some traditions, Jason’s hatred of Pelias was provoked when he discovered that Pelias had murdered his family while he was away. Some accounts claimed that Pelias had killed or caused the death of Aeson, Jason’s father, while others said that he was responsible for the deaths of Jason’s mother and brother as well.[57]

Eager to please her new husband, Medea employed cunning and witchcraft to enact Jason’s revenge. First, she told Pelias’ daughters that she could use her magic to restore the youth of their old father. To prove that she had this power, she slaughtered an old ewe, cut it into pieces, and boiled the pieces in a cauldron. After chanting magical incantations and sprinkling magical herbs, the cut-up ewe was transformed back into a lamb.

Pelias’ daughters were impressed by this trick and immediately cut their father into pieces, just as Medea had done to the ewe. But Medea did not use her magic to rejuvenate him. Pelias therefore died at his own daughters’ hands.[58]

This 2nd century Roman copy of a Greek relief shows Medea and the daughters of Pelias, at the Altes Museum in Berlin.

Frans VanderwalleCC BY-NC-SA 2.0In some accounts, Medea then used her magical abilities to rejuvenate Jason.[59] In others, she rejuvenated his old father Aeson (who, in these versions, had not been killed by Pelias).[60]

Following Pelias’ death, Jason and Medea left Iolcus, though the details of their departure vary depending on the source. In the best-known tradition, they were banished by Acastus, Pelias’ son.[61] But in another tradition, they left of their own free will after Jason made Acastus king of Iolcus.[62]

In one account, Jason and Medea then settled in Cercyra, where their son Mermerus was killed by a lion.[63] In a different account, they went to Thesprotian Ephyra in northwestern Greece.[64] But the most familiar tradition says that they ended up in Corinth. There they lived as exiles from their respective homelands—though one source claimed that Medea ultimately became the queen of Corinth, with Jason ruling as king by her side.[65]

Other Exploits

In Greek mythology, Jason is important almost exclusively for his role as the leader of the Argonauts. He did, however, participate in a few other heroic exploits as well. He took part in the funeral games of his uncle Pelias, which attracted some of the greatest heroes of the time (including many Argonauts who had sailed to Colchis with Jason).[66]

Jason was also one of the heroes summoned by Meleager to participate in the Calydonian Boar Hunt, the other famous heroic exploit of his generation. Artemis had sent the Calydonian Boar to terrorize the kingdom of Calydon after Oeneus, the king of Calydon, angered her. Oeneus’ son Meleager led a band of heroes (including Jason, in many accounts) to hunt down the boar.[67]

In another story, Jason—with the help of Peleus and the Dioscuri—ended up waging a war against Iolcus while it was being ruled by Acastus. Jason and his allies defeated Acastus and destroyed the city.[68]

Finally, one historian wrote that Jason accompanied Medea and her son Medus back to Colchis, where Aeetes, his old enemy, had been overthrown. There he helped restore Aeetes to power and even expanded the Colchian empire through war.[69]

The Wrath of Medea

In what has become the most popular account, Jason and Medea lived together for ten years, until Jason decided to leave Medea for another woman. The new object of Jason’s affections was usually said to have been a princess named either Creusa or Glauce,[70] the daughter of the Corinthian king Creon (though in some traditions the father of Jason’s betrothed was Creon’s son Hippotes).[71]

Jason’s betrayal drove Medea into an insane fury. She sent Creusa (or Glauce) a poisoned robe: as soon as the poor woman put it on, she burst into flames. Her father and the attendants who tried to help her were burned alive with her.

In what seems to have been the oldest version of the myth, Medea then fled from Corinth, leaving her children behind to be torn apart by a mob of angry Corinthians.[72] But in the more famous version, Medea wanted to hurt Jason even more and so murdered the children herself.[73]

Death

After his betrayal of Medea and the deaths of his children, Jason lost divine favor. In Euripides’ Medea, Jason’s death is foretold by Medea before she leaves Corinth:

...you, as is fitting, shall die the miserable death of a coward, struck on the head by a piece of the Argo, having seen the bitter result of your marriage to me.[74]

Sure enough, there was a tradition in which Jason was killed when a beam from the Argo fell on him and killed him (in one account, this happened while Jason was sleeping underneath the ship).[75]

But in another tradition, Jason’s grief ultimately became so great that the hero killed himself.[76] Only one source reports that Jason died together with Creusa/Glauce, his Corinthian would-be bride, when Medea caused her to burst into flames.[77]

Worship

Jason seems to have received hero-worship in parts of the ancient Greek world. The first-century BCE geographer Strabo mentions a temple of Jason in Abdera, a Greek city in Thrace.[78] There were also temples and towns called “Jasonia” (and one temple of “Athena Jasonia”) scattered throughout Anatolia.[79]

Popular Culture

In popular culture, Jason is perhaps best known from the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts. But he has appeared in other film and television adaptations of Greek myths, including the 1958 film Hercules and the 1990s television series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys. The myth of Jason was the inspiration for the BBC series Atlantis, which aired from 2013 to 2015 (and whose main character is named Jason).

Jason has also been kept alive in modern literature. Robert Graves’ Hercules, My Shipmate (1944) and Henry Treece’s Jason (1961) are historical fiction novels based on the adventures of Jason and the Argonauts (though with the supernatural elements largely removed). Jason also features in some of Rick Riordan’s novels: one of the main characters in the Heroes of Olympus series is named Jason.

Finally, Jason has appeared as both protagonist and antagonist in a number of video games, such as Age of Mythology (2002), God of War II (2007), and Fate/Grand Order (2015).