Bellerophon

Dispute between Minerva and Neptune over the Naming of the City of Athens by René-Antoine Houasse (ca. 1689)

Palace of VersaillesPublic DomainOverview

As a son of Poseidon, Bellerophon was destined for greatness from early on. Following a series of accidents and misadventures in his youth, Bellerophon found himself in the faraway kingdom of Lycia. There, he battled the Chimera, the Amazons, and other fearsome enemies.

Bellerophon’s successes were due in no small part to Pegasus, the immortal winged horse that Bellerophon had tamed. Eventually, however, Bellerophon fell out of the gods’ favor. Because of a terrible act of hubris, Bellerophon was punished by the gods and became an outcast.

Who were Bellerophon’s parents?

Bellerophon was usually called the son of Poseidon, god of the sea. His mother was Eurynome or Eurymede, wife of the Corinthian king Glaucus (who in some sources was Bellerophon’s father instead of Poseidon).

Dispute between Minerva and Neptune over the Naming of the City of Athens by René-Antoine Houasse (ca. 1689)

Palace of VersaillesPublic DomainWhat were Bellerophon’s attributes?

Bellerophon was a famous hero and prince; like other mythical heroes, he was known for his courage. But Bellerophon eventually succumbed to his own hubris. In the end, the gods punished him for attempting to transgress mortal limits.

Perhaps the most recognizable of Bellerophon’s attributes was his immortal winged horse Pegasus. Bellerophon tamed Pegasus with the help of Athena and rode him into battle against his enemies, including the monstrous Chimera.

Fresco in the third style showing Bellerophon (left) with Pegasus (center) and Athena (right), from the House of Lucius Betucius in Pompeii (1st century CE)

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg / Sergey SosnovskiyCC BY-SA 4.0How did Bellerophon die?

Bellerophon’s impressive achievements eventually went to his head, and the hero decided that he deserved to join the company of the gods. He tried to ride his winged horse Pegasus to the top of Mount Olympus, home of the mightiest Greek deities.

But the gods were disgusted by Bellerophon’s hubris—that is, his flagrant show of impiety and insolence. In one familiar tradition, Zeus sent a gadfly to sting Pegasus until the horse threw his rider. Bellerophon fell to the earth and was either killed or spent the rest of his life as a cripple.

Jupiter and Bellerophon (17th century)

National Museum, StockholmPublic DomainBellerophon Slays the Chimera

Bellerophon’s most glorious moment was probably his battle with the Chimera. The Chimera was a monster combining the features of a goat, a lion, and a snake. It had multiple heads, one of which breathed fire.

Iobates, the king of Lycia in Anatolia, had been told (falsely) that Bellerophon had tried to rape his daughter. Not wanting to kill a guest in cold blood, Iobates sent Bellerophon against the fearsome Chimera, believing that the monster would kill him. But with the help of his winged horse Pegasus and his own strength, Bellerophon slew the Chimera, winning great fame in the process.

Pebble mosaic showing Bellerophon fighting the Chimera (ca. 300–270 BCE)

Archaeological Museum of RhodesPublic DomainEtymology

The name Bellerophon may have been derived from the words belos (“projectile”) and phontēs (“killer”). Bellerophon would thus mean “he who kills with a projectile.” According to an alternative ancient etymology, Bellerophon received his name because he had killed a tyrant of Corinth named Bellerus; in this version, his name would mean “killer of Bellerus.”[1]

Modern scholars have suggested various Indo-European etymologies. Rhys Carpenter, for example, has argued that the name Bellerophon means “bane-slayer,” deriving from the rare word elleron (“evil”).[2] Joshua Katz subsequently suggested that the word “eleron” is related to an Indo-European word for a water snake or dragon. As a result, the name Bellerophon could also mean “dragon slayer.”[3]

Pronunciation

In ancient Greek, the name of the hero Bellerophon was usually spelled Βελλεροφόντης (Bellerophontes), though the alternative Βελλεροφῶν (Bellerophon) was also attested.[4]

English

Greek

Bellerophon Βελλεροφόντης or Βελλεροφῶν Phonetic

IPA

[buh-LER-uh-fon] /bəˈlɛrəfən/

Attributes

Bellerophon’s most distinctive attribute was his winged horse Pegasus; in antiquity, he was usually depicted riding him. Ancient art sometimes featured his battle with the Chimera as well.

A red-figure pottery plate showing Bellerophon riding Pegasus and a chimera (c. 400 BCE).

Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0Family

Bellerophon was born into the court of Glaucus, the king of Corinth, and his wife, whose name was either Eurynome[5] or Eurymede.[6] According to most accounts, however, Bellerophon’s true father was the sea god Poseidon. Bellerophon also had a younger brother, though ancient sources debate whether his name was Alcimenes, Deliades, or Peiren.[7]

Bellerophon’s wife was named either Alcimedousa, Anticleia, Pasandra, or Cassandra.[8] According to Homer, Bellerophon and his wife had three children together: Isander, Hippolochus, and Laodamia.[9] In some traditions, Bellerophon also fathered Hydissus by Asteria, the daughter of Hydeus.[10]

Mythology

Early Life

When he was very young, Bellerophon accidentally killed someone—in most versions, it was his own brother (whose name varies by the source). Bellerophon went to King Proetus of Argos to be purified of the crime.

Argos

While Bellerophon was in Argos, King Proetus’ wife (whose name was either Antea[11] or Stheneboea[12]) fell in love with him. Bellerophon rejected these advances, but Proetus’ wife took her revenge by telling her husband that Bellerophon had tried to rape her. She then demanded that Proetus put Bellerophon to death.

Proetus, not wishing to kill Bellerophon himself, sent the young hero to his father-in-law Iobates, the king of Lycia. Bellerophon was given a letter for Iobates: it instructed Iobates to put the carrier of the letter to death. This was how Bellerophon came to Lycia, a kingdom in modern Turkey.

The Chimera and Other Adventures

When Bellerophon reached Lycia and delivered Proetus’ letter, Iobates was reluctant to kill Bellerophon himself; like Proetus, he did not wish to incur the gods’ anger by violating the laws of hospitality (xenia). Iobates decided to send Bellerophon to kill the Chimera, which he considered an impossible task.

Chimera of Arezzo (c. 400 BCE) at the National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0The Chimera was a terrible monster with a hybrid body: part lion, part goat, and part snake. It also breathed fire.

Bellerophon learned that he could not defeat the Chimera without the help of Pegasus, an immortal winged horse who had sprung from the blood of the beheaded Medusa. According to Pindar’s Olympian Ode 13, the most complete ancient account of Bellerophon’s capture of Pegasus, Bellerophon was helped in his task by Athena and the prophet Polyidus.[13] In other traditions, however, Bellerophon’s father Poseidon was the one who gave him Pegasus.[14]

With Pegasus, Bellerophon was able to attack the Chimera in its mountain lair. After a fierce struggle, Bellerophon prevailed and killed the Chimera.

Iobates then sent Bellerophon against other dangerous opponents, including the Solymi, the Amazons, and a boar. When Bellerophon completed these tasks, too, Iobates sent the best Lycian soldiers to ambush him. But the attack failed, and Bellerophon killed Iobates’ soldiers. Iobates, impressed by the young hero, finally gave up trying to kill him. Instead, he married Bellerophon to one of his daughters and made him his heir.

Downfall

Though accounts of Bellerophon’s downfall and death differ somewhat, they all agree that towards the end of his life, Bellerophon lost the gods’ favor.

According to the best-known version, Bellerophon became so arrogant that he felt he should live among the gods in heaven. This did not end well. As the poet Pindar wrote,

… winged Pegasus threw his master Bellerophon, who wanted to go to the dwelling-places of heaven and the company of Zeus. A thing that is sweet beyond measure is awaited by a most bitter end.[15]

In most stories, Bellerophon survived his fall but became lame and was forced to wander the earth for the rest of his life in disgrace. Homer’s Iliad, the earliest source to recount the myth, does not say how Bellerophon offended the gods—only that the former hero spent the remainder of his days wandering in the Aleian Field.[16] Finally, according to Hyginus, Bellerophon was killed when he fell from Pegasus.[17]

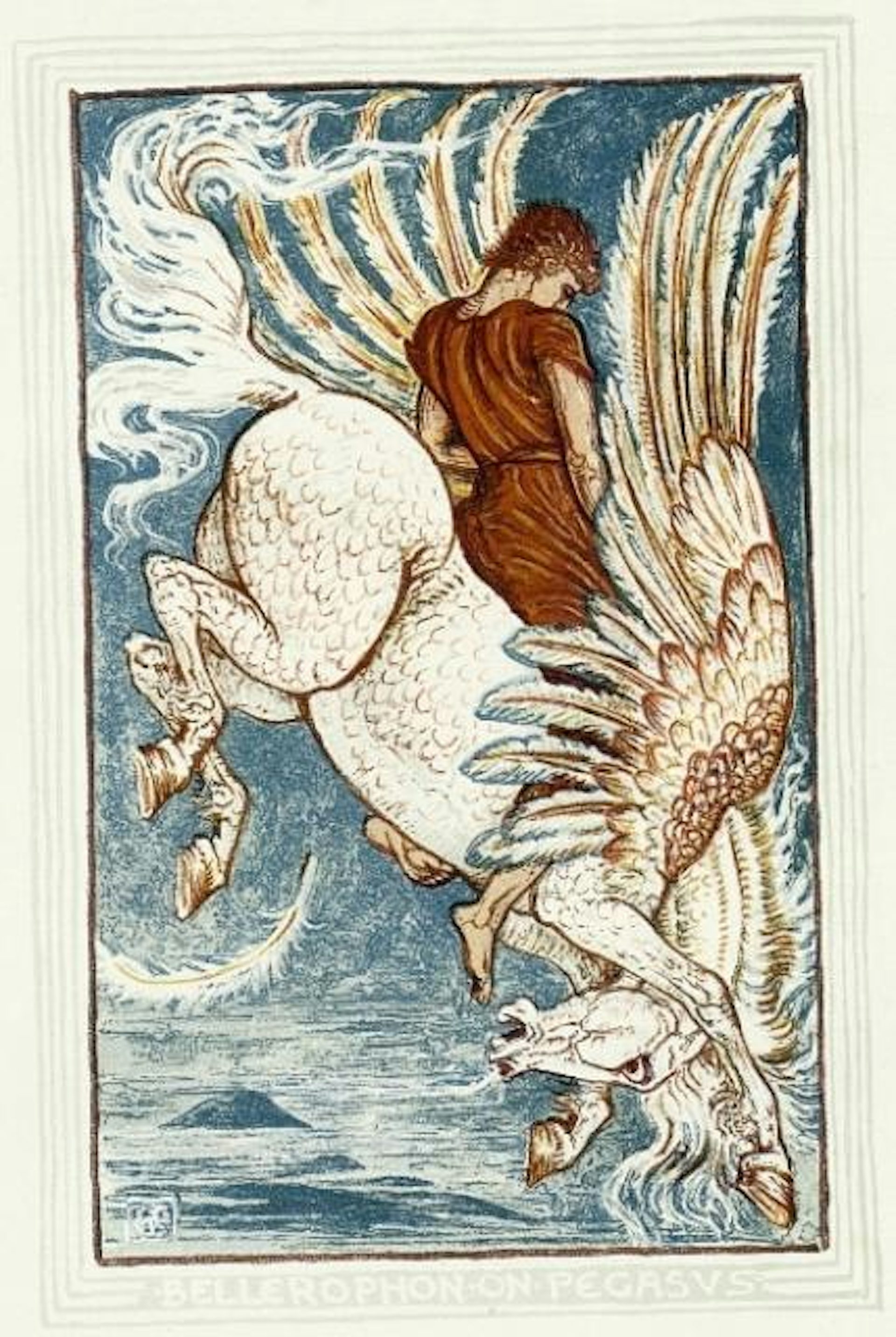

Bellerophon on Pegasus by Walter Crane (1892).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainWorship

Bellerophon received cult worship in Corinth, which was said to have been his hometown. It contained the Craneion, a sanctuary dedicated to Bellerophon.[18] Bellerophon was also an object of hero cult in Lycia.[19]

Bellerophon was worshipped as the founding hero of the Carian city of Baryglia. In antiquity, he was claimed as the ancestor of Leucippus, the founder of Magnesia on the Maeander. He was also possibly connected to the family of Cossutius Sabula in the late Roman Republic.

As the tamer of Pegasus, Bellerophon was sometimes revered as the inventor of horsemanship.[20] In some sources, his desire to ascend to the heavens contributed to his image as the first astronomer.[21]

Pop Culture

There are relatively few modern pop culture representations of Bellerophon. He is the main character of Cathleen Townsend’s 2019 novel Bellerophon: Son of Poseidon. He also features in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson’s Heroes. Finally, Bellerophon is a minor character in the 1990s TV show Xena: Warrior Princess, where he is portrayed by the New Zealand actor Craig Parker.