Heracles

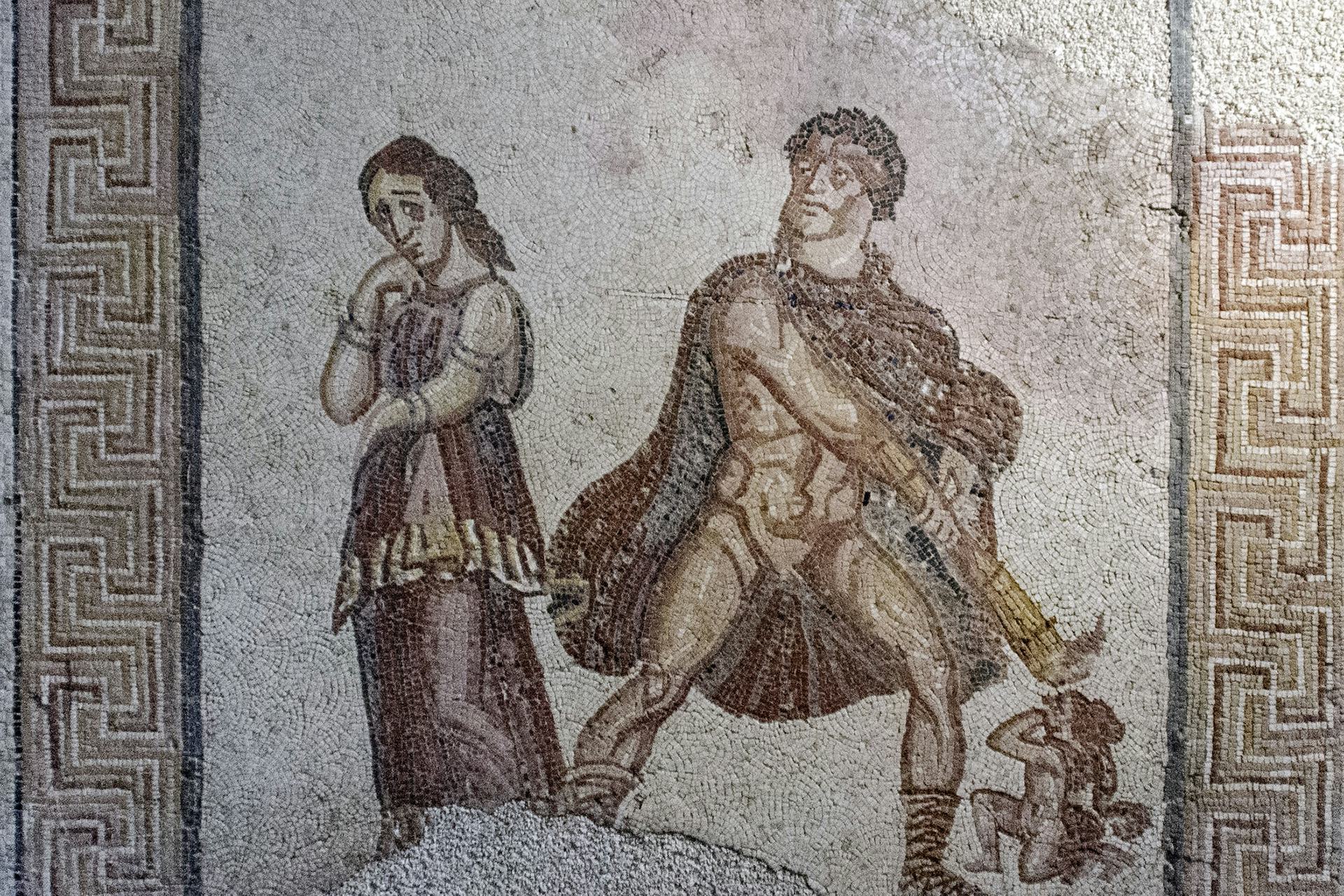

Mosaic panel showing the mad Heracles (center) killing his child (bottom right) as his wife Megara (left) stands by (third or fourth century CE). From the Villa Torre de Palma near Monforte.

National Archaeology Museum, Lisbon / Ángel M. FelicísimoCC BY 2.0Overview

Heracles, the son of Zeus and Alcmene (a mortal woman), was a Greek hero and demigod. Because he was the product of one of Zeus’ many affairs, Heracles was hated and hounded by Zeus’ jealous wife Hera. Hera ensured that Heracles’ life was filled with hardship and tragedy.

Of all Heracles’ heroic deeds, the most important were the Twelve Labors, which the hero was forced to perform for his cousin Eurystheus, the High King of Mycenae. Through these labors as well as his many other exploits, Heracles became known as a champion of civilization and a slayer of monsters.

Heracles, like the other heroes of ancient Greece, was not without his flaws. He was hot-tempered, violent, and lustful, and these characteristics contributed to his struggles as much as Hera’s hatred did. Despite his failings, Heracles was promoted to the ranks of the gods after his death.

Whom did Heracles marry?

Heracles’ first wife was a woman named Megara. But their marriage was cut short when Heracles was driven mad by Hera and killed his own children (in some versions, he killed Megara, too). Heracles’ final wife, Deianira, inadvertently caused the hero’s death. But he had many lovers in between, including the Eastern queen Omphale, who would wear Heracles’ lion skin while forcing the hero to work the loom.

After he died and became a god, Heracles married Hebe, the goddess of youth and a daughter of Hera. This marriage represented Heracles’ reconciliation with the stepmother who had made him suffer throughout his life.

Mosaic panel showing the mad Heracles (center) killing his child (bottom right) as his wife Megara (left) stands by (third or fourth century CE). From the Villa Torre de Palma near Monforte.

National Archaeology Museum, Lisbon / Ángel M. FelicísimoCC BY 2.0How did Heracles die?

Heracles was accidentally killed by his final mortal wife, Deianira. In the most familiar version of the myth, Deianira feared that Heracles loved another woman, so she sprinkled his shirt with a love potion that had been given to her by the Centaur Nessus. But Nessus had deceived Deianira: the “love potion” was actually laced with the toxic blood of the Hydra.

When Heracles put the shirt on, he immediately began to burn up. Realizing that he was dying, he had a great pyre built. As the pyre burned, Heracles’ soul ascended to the heavens to join the gods.

Nessus and Deianeira by Arnold Böcklin (1898)

Museum Pfalzgalerie KaiserslauternPublic DomainWas Heracles a god?

Heracles was technically a demigod, the son of a god and a mortal. However, it was said that after his death, Heracles was granted immortality and a seat beside the gods on Mount Olympus. Thus, he was one of the few Greek heroes to be worshipped as a full-fledged god.

The cult of Heracles was widespread in ancient Greece. He was especially important in the Boeotian city of Thebes, where he was born, and in Dorian cities such as Sparta, which claimed him as an ancestor.

The "Farnese Hercules" by Glycon of Athens (early 3rd century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5The Twelve Labors of Heracles

Heracles completed his famous “Twelve Labors” after killing his family in a fit of madness. This madness had been inflicted by Hera, who wanted to make Heracles suffer. To atone for his crime, Heracles was commanded to perform a series of tasks or “labors” for his cousin Eurystheus, the king of Mycenae.

Eurystheus hated and feared Heracles, so he assigned him the most challenging and dangerous tasks he could think of (in some accounts, Hera helped with this). Eurystheus sent Heracles to fight fearsome monsters such as the Nemean Lion, the Hydra, and even Cerberus, the guard dog of Hades.

But Heracles—much to the disappointment of both Eurystheus and Hera—successfully completed each of his labors, which only served to increase his fame.

Hercules and the Hydra by John Singer Sargent (1921)

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainEtymology

The name Heracles is derived from the name of the goddess Hera and the Greek word kleos (meaning “glory”)—it can be translated as “Hera’s glory.” His name is thus an homage to the goddess who was his lifelong enemy.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Heracles Ἡρακλῆς Phonetic

IPA

[HERR-ə-kleez] /ˈhɛrəkliːz/

Alternate Names

According to some traditions, Heracles was originally named Alcaeus in honor of his grandfather and was only renamed Heracles later in an attempt to placate a furious Hera. He was known as Hercules in Roman literature.

Attributes

Said in Greek myth to have been the strongest man who ever lived, Heracles was always depicted as large and muscular. Usually, he can also be identified by his weapons: his club, his bow, and the skin of the Nemean Lion (which he wore as armor).

Family

Heracles was the son of Zeus, the king of the Greek gods, and a mortal woman named Alcmene.[1] Alcmene was the daughter of Electryon, the king of Mycenae and a son of the hero Perseus. Alcmene’s husband, the hero Amphitryon, was from an important family, too, also tracing his lineage to Perseus through his father, Alcaeus.

Heracles grew up in Thebes with his half-brother Iphicles; later, Iphicles’ son Iolaus would accompany Heracles on many of his adventures.

Over the course of his storied life, Heracles had many wives and lovers. He was survived by a literal army of children (the Heracleidae), who conquered many of the Greek cities after the Trojan War.

Mythology

Birth and Childhood

Heracles was the son of Zeus and Alcmene, the wife of the hero Amphitryon. Zeus had approached Alcmene in the form of her husband, who was away at war at the time. The same night Zeus slept with Alcmene, Amphitryon came home early and also slept with her. Alcmene was thus impregnated twice on the same night. She eventually gave birth to twins: one of them, Heracles, was Zeus’ son, while the other, Iphicles, was Amphitryon’s.

From the very beginning, Heracles was hated by Hera, Zeus’ queen. Hera was jealous of her husband Zeus’ mortal lovers and children, and even before Heracles was born she tried to destroy him.

While Alcmene was in labor with her twins, Hera tricked Zeus into promising that the next male child born into the House of Perseus would become High King. Hera then forced Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, to delay the births of Heracles and Iphicles by shutting Alcmene’s womb; at the same time, she caused Heracles’ cousin Eurystheus to be born early. Both Heracles and Eurystheus were male descendants of Perseus, but since Eurystheus was born first, Hera had ensured that he and not Heracles would be High King.

According to one myth, Amphitryon and Alcmene feared Hera’s wrath and therefore left Heracles in the wilderness to die. But he was rescued by the goddess Athena, Zeus’ daughter and thus Heracles’ half-sister. Athena brought the infant Heracles with her to Olympus, where she convinced Hera to nurse him. Hera, not recognizing Heracles, took pity on the child and gave him her breast.

But the spirited Heracles nursed so strongly that he hurt Hera. When the goddess pushed him away, her milk sprayed across the heavens and formed the Milky Way. Athena then brought the infant back to Alcmene to be raised by her and Amphitryon (who became his foster father).[2]

In another myth, Hera sent two snakes to kill Heracles when he was still an infant. While Iphicles screamed in fear, Heracles grabbed one snake in each hand and strangled them. His mother found him unharmed and playing with the dead snakes as though they were toys. Amphitryon, shocked, consulted the prophet Tiresias, who prophesied that Heracles would become a great hero.

Youth

Heracles’ physical strength went hand in hand with a quick temper. While still only a boy, Heracles accidentally killed his music teacher, Linus, in a fit of rage, so Amphitryon sent him away to herd cattle in the mountains.

In one story, invented in the fifth century BCE by the philosopher Prodicus, the young Heracles was approached by the goddesses Virtue and Vice while tending the cattle. The two goddesses offered Heracles a choice between a pleasant but undistinguished life and a hard but glorious life. Heracles chose the latter.[3]

Choice of Hercules by Thomas Sully (1819).

Princeton University Art MuseumPublic DomainLater, Heracles married Megara, the daughter of the Theban king Creon. But Hera had not forgotten her hatred of Heracles: she caused him to go mad and kill his family (in some versions, he murdered both Megara and his children, while in others he killed only his children).[4]

After Heracles was cured of his madness, he consulted the oracle of Delphi to find out how to atone for his crime. He was told to go to his cousin Eurystheus in Mycenae and perform whatever tasks he was assigned. However, in Euripides’ tragedy Heracles, probably performed around 416 BCE, Heracles was driven mad and killed his family only after his service to Eurystheus.

Labors

The most familiar exploits of Heracles’ heroic career are the famous Twelve Labors (sometimes also called the “Labors of Heracles” or the “Twelve Labors of Heracles”). These were the tasks that Heracles was forced to perform for his cousin Eurystheus, the High King of Mycenae.

In many accounts, it was Hera herself who helped Eurystheus devise the most difficult and deadly tasks, hoping to destroy Heracles once and for all. But Heracles managed to successfully complete each of his labors, acquiring fame and immortal glory in the process.

In the best-known version of the myth, Heracles was initially instructed to perform ten labors for Eurystheus. But after completing his tenth labor, Eurystheus found a flimsy excuse to add two more, bringing the total to twelve. The canonical list and order of the labors, as reported by the mythographer Apollodorus, is as follows:[5]

Labor #1: The Nemean Lion

Heracles’ first labor was to slay the Nemean Lion, a lion that was terrorizing the city of Nemea. Since the lion’s skin was invulnerable, Heracles could not use his weapons against it and had to kill the lion with his bare hands.

Vase painting showing Heracles wrestling the Nemean Lion by Psiax (520–500 BCE).

ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0After completing this labor, Heracles wore the skin of the Nemean Lion as armor.

Labor #2: The Lernaean Hydra

Heracles’ next labor was to slay the Hydra, a monster with multiple serpent heads (the number of heads varies depending on the source) that lived in a swamp near Lerna.

Heracles discovered that each time one of the monster’s heads was cut off, two new heads would grow in its place. He finally managed to destroy the Hydra with the help of his nephew Iolaus: every time Heracles cut off a head, Iolaus would cauterize the wound with a torch, thus preventing new heads from growing.

After defeating the Hydra, Heracles dipped his arrows in its poisonous blood.

Labor #3: The Ceryneian Hind

Since the Ceryneian Hind (sometimes called the Golden Hind) was sacred to Artemis, Heracles was told to bring it to Eurystheus alive rather than kill it (according to most versions).[6]

This was no small task: the Ceryneian Hind was a massive female deer noted for its incredible speed. According to some sources, it had antlers like a stag and breathed fire. Eventually Heracles managed to run down the hind and presented it to Eurystheus.

Labor #4: The Erymanthian Boar

Heracles was then tasked with capturing the Erymanthian Boar, a huge and violent boar on the loose around the marsh of Erymanthia.

The scene in which Heracles brings the boar to Eurystheus was popular in early Greek art: according to this tradition, when Eurystheus saw Heracles coming back with the Erymanthian Boar on his shoulders, he became terrified and hid in a large ceramic storage container called a pithos.

Roman marble relief with Heracles carrying the Erymanthian Boar (27 BCE–68 CE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainLabor #5: The Augean Stables

Heracles’ next labor was as humiliating as it was difficult: he was sent to clean the stables that housed the immortal cattle of King Augeas (a gift from his father Helios). Heracles managed to complete the labor quickly and ingeniously: he diverted the nearby rivers Alphaeus and Penaeus into a ditch he dug around the stables, thus washing the stables clean.

Labor #6: The Stymphalian Birds

Heracles was then sent to get rid of the Stymphalian Birds, man-eating, bronze-beaked birds who were terrorizing a forest near Stymphalia. Heracles used a rattle given to him by Athena to frighten the birds out of hiding. When the birds flew out of the forest, Heracles was able to shoot and kill many of them with his arrows tipped with the Hydra’s poison.

Labor #7: The Cretan Bull

Heracles’ seventh labor took him to the island of Crete. Poseidon had originally sent the Cretan Bull as a gift to his son Minos. It was intended to be sacrificed to Poseidon, but Minos wanted to keep the bull for himself. Poseidon became angry and sent the bull to ravage the land around Minos’ kingdom of Knossos (but only after the bull fathered the Minotaur).

After Heracles captured the bull, Eurystheus released it in Marathon. There, it continued to terrorize the city until it was killed by the Athenian hero Theseus.

Labor #8: The Mares of Diomedes

Heracles was then sent to steal the mares of Diomedes, who had been trained by their master to eat human flesh. Heracles accomplished this by feeding Diomedes to his own horses, then binding the animals’ mouths shut and taking them to Eurystheus.

Labor #9: The Girdle of Hippolyta

Heracles’ next task was to steal the magnificent girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyta, which she had received as a gift from her father Ares. When Heracles arrived, he was quickly attacked by the warlike Amazons, but he managed to defeat Hippolyta and bring her girdle to Eurystheus.

Labor #10: The Cattle of Geryon

Heracles’ tenth labor took him far from the Greek world, to the western Mediterranean. His task was to steal the cattle of Geryon, a monster with three heads and six arms. These cattle were guarded by another multi-headed creature, the two-headed dog Orthrus. Heracles killed both Orthrus and Geryon (as well as Geryon’s herdsman Erytion) and herded the cattle, with some difficulty, to Eurystheus in Greece.

Detail of Twelve Labors Roman mosaic from Lliria, showing Heracles battling Geryon (3rd century CE).

Benjamin Nunez GonzalesCC BY-SA 4.0Labor #11: The Apples of the Hesperides

According to the best-known version of the myth, Heracles was originally instructed to complete only ten labors for Eurystheus. But after Heracles had finished his tenth labor, Eurystheus demanded two more. He claimed that the slaying of the Hydra did not count because Heracles had been helped by his nephew Iolaus, and the cleaning of the Augean stables did not count because Heracles had received payment for his labor.

Eurystheus sent Heracles to retrieve the golden apples from the mythical Hesperides, located in a remote region in the far western Mediterranean. According to some versions, Heracles caught the shapeshifting Nereus and forced him to reveal the location of the Hesperides; in other versions, it was the Titan Prometheus who gave this information to Heracles.

The golden apples, which were sacred to Hera, were protected by a many-headed dragon named Ladon. Heracles shot the dragon but was unable to gain entry into the garden.

In the end, Heracles managed to convince the Titan Atlas to get the apples for him (in some versions, Atlas was the father of the maidens guarding the garden). Since Atlas had been tasked by Zeus to hold up the heavens for eternity, Heracles agreed to shoulder the burden for him while he retrieved the apples.

When Atlas came back with the promised fruit, he tried to leave Heracles holding the heavens for him, but Heracles was able to trick Atlas into taking them back. Heracles then collected the apples and returned to Eurystheus.

Labor #12: Cerberus

Heracles’ final labor was the most daunting: to go down to the Underworld and bring back Cerberus, Hades’ three-headed guard dog. Against all odds, Heracles was able to cross into the Underworld, wrestle Cerberus, and convince Hades to let him bring the dog to Eurystheus.

Heracles and Cerberus by Antonin Pavel Wagner (1893) at Hofburg palace, Vienna.

JebulonCC0Other Myths

There is a similar myth about Heracles being forced to undergo a period of servitude in order to atone for a crime: this time, Heracles was told to serve the Lydian queen Omphale after he went mad and threw his friend Iphitus from a city wall to his death.

As Omphale’s slave, Heracles was forced to wear women’s clothing and do what was traditionally considered women’s work (such as weaving) while Omphale wore his lion skin and wielded his club. Eventually, Omphale freed Heracles and became his wife.

Hercules and Omphale by Luigi Garzi (circa 1710).

The Paul J. Getty MuseumPublic DomainOther myths take Heracles to almost every corner of the known world. In Africa, Heracles fought and killed the giant Antaeus. A son of the earth, Antaeus was invincible as long as he was in contact with the ground. Heracles finally defeated him by lifting him into the air and breaking his back.

In Asia, Heracles sacked Troy after its king, Laomedon, cheated him. Laomedon had promised to give Heracles his prize horses if the hero rescued his daughter Hesione from a sea monster. Heracles saved Hesione, but Laomedon refused to hand over the horses. This did not sit well with Heracles, who sacked Troy, killed Laomedon, and claimed the horses he had been promised.

On another adventure, in the Caucasus, Heracles freed the Titan Prometheus from his torture. As punishment for stealing fire from the gods, Zeus had chained Prometheus to a mountain and sent an eagle every day to eat his liver, which would grow back only to be eaten again the next day. Heracles killed the eagle and broke Prometheus’ chains.

Heracles also traveled with Jason and the Argonauts to Colchis (on the eastern coast of the Black Sea) to steal the Golden Fleece from King Aeetes. Heracles was accompanied by the young Hylas, who was his shield bearer and lover. On one of the Argonauts’ stops on their way to Colchis, however, Hylas disappeared. Heracles went in search of him, and the Argonauts left without them. Heracles thus did not make it to Colchis with the Argonauts.

According to some traditions, Heracles even went up to Olympus to help the gods in their war against the Giants.

Death

After defeating the river god Achelous in a wrestling competition, Heracles carried away the Calydonian princess Deianira as his bride. As the newlyweds traveled to Heracles’ home, the centaur Nessus offered to help Deianira cross a river. But while Heracles was still making the crossing, Nessus tried to run off with Deianira. Heracles, angry, shot Nessus with one of the arrows tipped with the poisonous blood of the Hydra.

The dying Nessus, knowing that his blood had been tainted by the Hydra’s poison and hoping for revenge, gave his bloody tunic to Deianira. He told her to keep the tunic and to use it as a love charm if she ever needed to reignite her husband’s feelings for her.

Years later, Deianira became convinced that Heracles had a new lover. Remembering Nessus, she gave Heracles the bloody tunic. As soon as Heracles put it on, however, he was poisoned by the blood of the Hydra. When Heracles tried to remove the tunic, his skin came off with it.

The Death of Hercules by Francisco de Zurbarán (1634).

Prado MuseumPublic DomainHeracles began dying in extreme agony. He built a pyre, climbed on top of it, and begged his family and friends to set it on fire. Only Philoctetes (or Philoctetes’ father, Poeas, in some versions) agreed to do so, and in return Heracles gifted him his bow and arrows. Many years later, Philoctetes would use the bow of Heracles in the Trojan War.

After his body was consumed by the flames, Heracles became a god. When Heracles arrived at Olympus, Hera was finally persuaded to put aside her hatred of him, and he was married to Hebe, one of Zeus and Hera’s daughters and the goddess of youth.

Children

During his life, Heracles was married several times and took many lovers, most of whom gave him children (primarily boys). Some of his most famous children included Telephus, his son by Auge, and Tlepolemus, his son by Astyoche. Both Telephus and Tlepolemus played a role in the saga of the Trojan War.

Heracles’ most important son by his wife Deianira, Hyllus, would invade the Peloponnese and fight a war against Eurystheus after Heracles’ death. Several generations later, Heracles’ descendants (also called the Heraclidae) invaded Greece and took over the Peloponnese. This would later come to be known as the “Dorian Invasion.” Throughout Greek history, the Spartans and many other Peloponnesian kingdoms who identified as Dorians claimed that they were descended from Heracles.

Worship

Festivals

In many parts of Greece, Heracles was worshipped as a hero as well as a god, and festivals in his honor were usually called “Heracleia.” Such festivals are known to have been celebrated throughout the important regions of Attica (especially Cynosarges and Marathon),[7] the Peloponnese (Sicyon, Sparta, etc.),[8] and Boeotia (Thebes, Thisbe, Tipha, Siphae, etc.).[9]

In northern Greece, a festival of Heracles was celebrated in Ambracia, the main city of Epirus.[10] Another festival in Heracles’ honor, called the Iolaia, was held in the city of Thebes.

Temples

There were many major and minor temples of Heracles scattered across the Greek world. In Attica, important sanctuaries to Heracles were located at Cynosarges and Marathon, both sites where the Heracleia was celebrated. Numerous temples and sanctuaries of Heracles could also be found in Boeotia, including at Thebes, Thespiae, Thisbe, Tipha, and Orchomenus,[11] as well as at Argos and Nemea.[12] In Sparta, we are told that there was a temple of Heracles close to the city walls.[13]

Heracles’ sanctuary in Thebes seems to have been particularly elaborate, boasting temples, a gymnasium, and a race course. Also in Thebes were the tombs of the children of Heracles and Megara, whom Heracles had killed in a fit of madness; nearby, a kind of religious relic, was a stone called the “Chastiser,” which Athena was thought to have thrown at Heracles to end his killing spree (and to prevent him from killing his foster father Amphitryon too).[14]

There were also more remote temples of Heracles. In northern Greece, there are traces of a temple dedicated to Heracles and his mother, Alcmene. On Mount Oeta, the site of Heracles’ death, a temple from the third century BCE has been excavated. There is also a Doric temple of Heracles, probably built in the beginning of the fifth century BCE, at Acragas in Sicily.

Temple of Heracles at Acragas (modern Agrigento) in Sicily (early 5th century BCE).

JarvisCC BY-SA 2.0The Romans, who worshiped Heracles as Hercules, dedicated various temples and altars to him in the city of Rome as well as throughout Italy and the Roman Empire.

Pop Culture

Heracles is one of the most commonly portrayed Greek mythological characters in modern popular culture (though he is usually called by his Roman name, Hercules). Heracles was featured in dozens of the “sword-and-sandal” films popular in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Some of the most famous of these include: Hercules (1958) and Hercules Unchained (1959), starring the bodybuilder Steve Reeves as Hercules; Jason and the Argonauts (1963); and Hercules in New York (1970), in which Hercules, played by the bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger, time travels to twentieth-century New York City.

The myth of Heracles was adapted for a younger audience in Disney’s Hercules (1997). In the 1990s, Kevin Sorbo played the hero in the television series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and in a few made-for-television movies. More recently, Hercules was played by Dwayne Johnson in Hercules (2014). Heracles (or Hercules) also features in other media, including Rick Riordan’s young adult book series Percy Jackson and the Olympians.

In popular culture, Heracles has usually been depicted as a strongman or brute: in television and film, for example, the role of Heracles/Hercules has typically gone to bodybuilders or athletes (Steve Reeves, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Dwayne Johnson, etc.). Heracles tends to be treated as the archetype of the mortal hero or demigod, with a strong emphasis on his larger-than-life exploits.