Dionysus

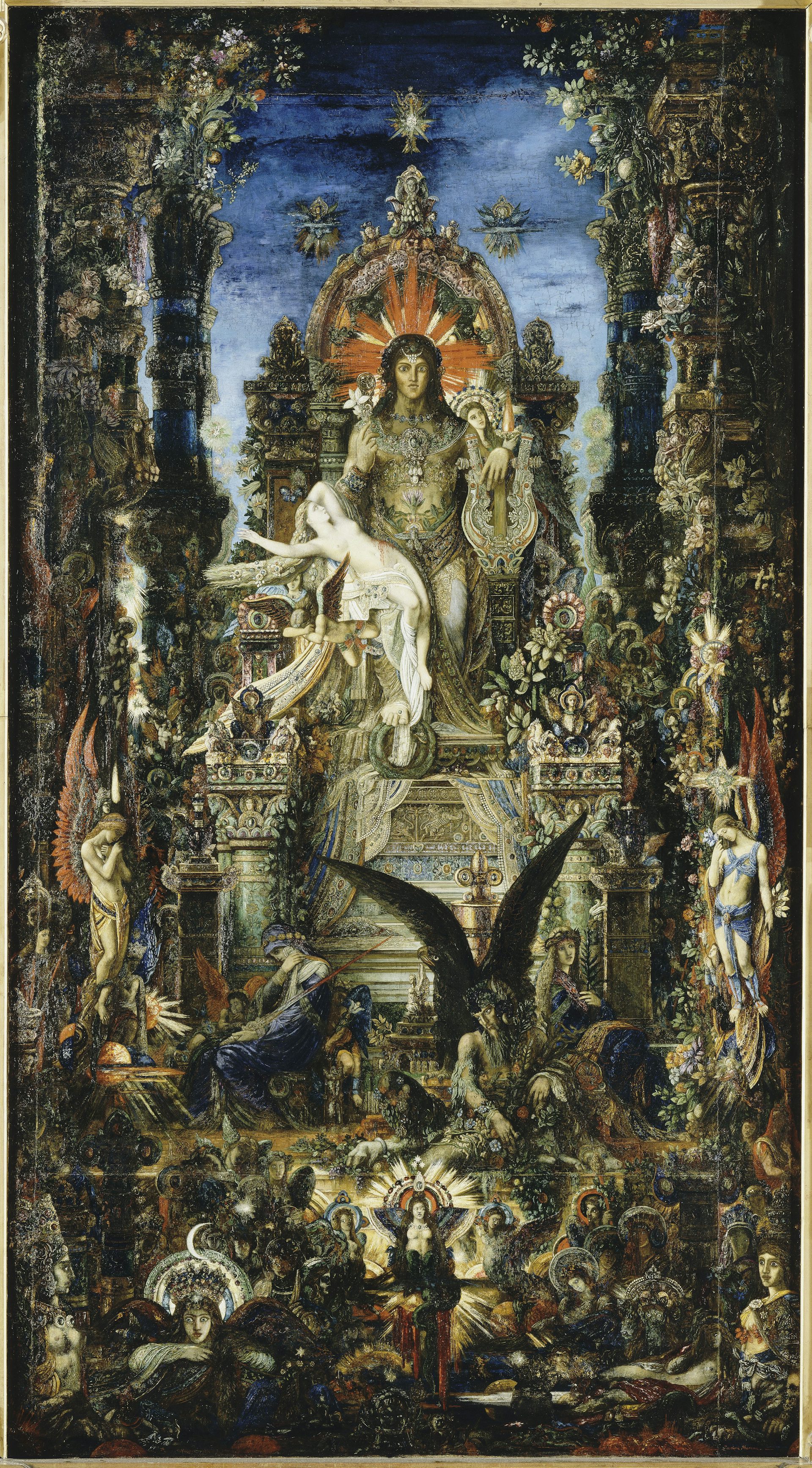

Jupiter and Semele by Gustave Moreau (between 1894 and 1895)

Musée National Gustave-Moreau, ParisPublic DomainOverview

Dionysus, the son of Zeus and Semele, was a Greek god who represented the more spontaneous and unrestrained aspects of human experience. He was the god of wine, winemaking, fertility, music, dance, and inspiration, and was sometimes counted among the Twelve Olympians—the most important gods of the Greek pantheon.

The mythology and cult of Dionysus were often characterized by madness. Some sources claimed that Dionysus used his invention of wine to drive his enemies mad, while others said that Dionysus himself went mad. Said to have traveled far and wide, Dionysus was regarded as a bringer of civilization in the form of wine cultivation—with both positive and negative consequences.

Key Facts

Jupiter and Semele by Gustave Moreau (between 1894 and 1895)

Musée National Gustave-Moreau, ParisPublic DomainWhat were Dionysus’ attributes?

Dionysus was usually imagined as a youthful god. His most common attributes pertained to his function as the god of wine and intoxication; these included grapevines or grapes and a special kind of ivy-covered wand called a thyrsus.

In art, Dionysus was often shown holding a large wine cup. He was also associated with wild cats, especially leopards and panthers; ancient artists liked to depict him riding these exotic creatures. His entourage included mythical beings such as satyrs and silens and frenzied female worshippers called maenads.

Sculpture of a drunken Dionysus and a satyr, 2nd century CE Roman copy after a Hellenistic Greek original

Palazza Altemps, Rome / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainHow was Dionysus worshipped?

Dionysus was worshipped throughout the Greek world, though the Greeks themselves thought of him as a foreign god imported from the East. The cult of Dionysus tended to revolve around ecstasy and intoxication; because of this, Dionysus was often viewed as a god who lived on the edge of civilization.

At the same time, Dionysus was worshipped as a god of culture and the arts. Indeed, it was at the annual festival of Dionysus in Athens that Greek tragedies and comedies—some of the most important literary creations of the ancient world—were performed in honor of Dionysus.

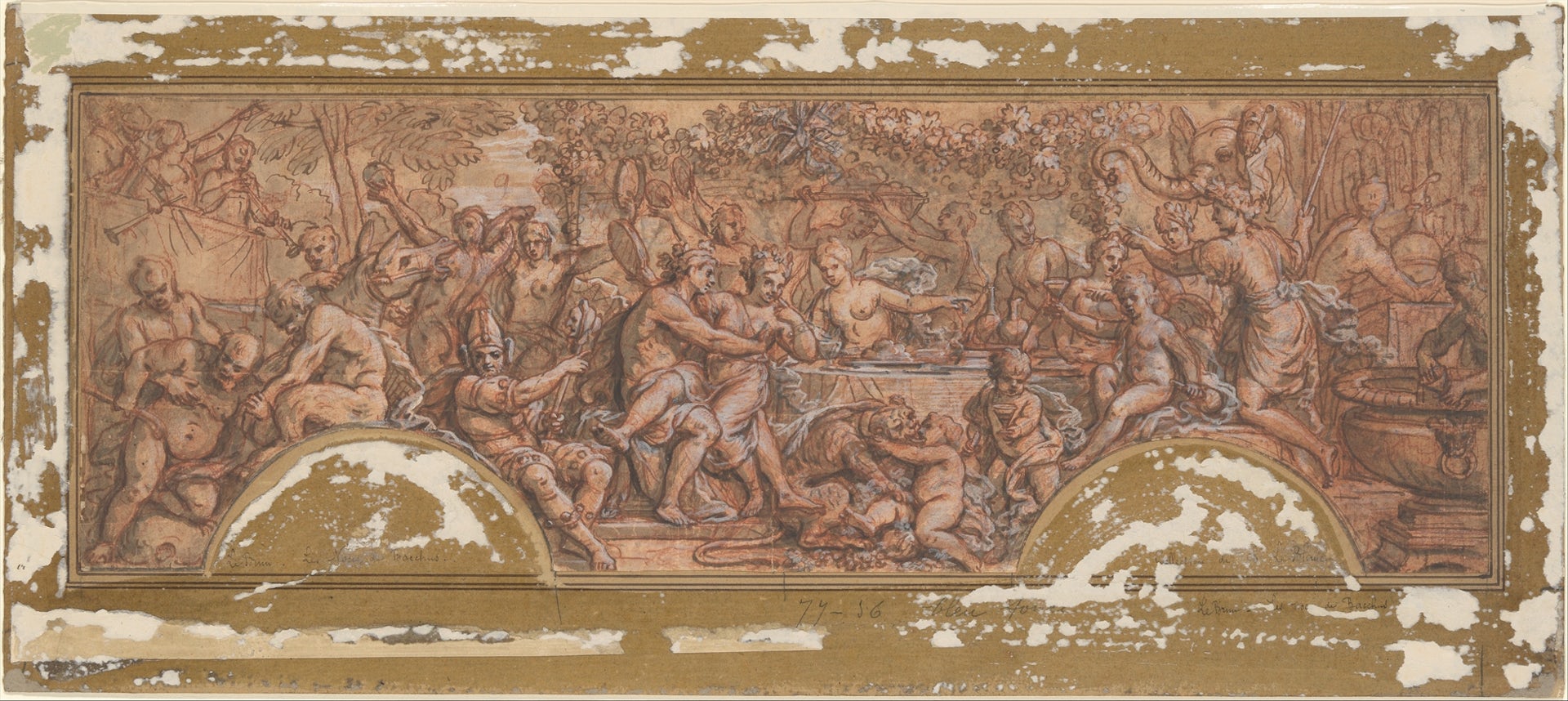

Sacrifice to Bacchus by Massimo Stanzione (ca. 1634)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainDionysus and Ariadne

Dionysus’ most famous consort was Ariadne, a Cretan princess who helped the hero Theseus defeat the Minotaur. After Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos, Dionysus happened to catch sight of her while reveling with his entourage. Enchanted by the beautiful princess, Dionysus whisked her away to become his lover.

The meeting between Dionysus (surrounded by his extravagant retinue) and the distraught Ariadne became an extremely popular subject in literature and art, both ancient and modern.

The Wedding of Bacchus and Ariadne by Guy Louis Vernansal the Elder, formerly attributed to Charles Le Brun (ca. 1709)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainRoles and Powers

As a god, Dionysus was primarily associated with wine and intoxication, though he was also worshipped in connection with ecstasy and inspiration, theater and the arts, and the afterlife.

Perhaps more than any other figure of Greek mythology, Dionysus blurred the natural, social, and cultural boundaries of his world. For example, though he was one of the most important gods of the Greek pantheon, he was also seen as an outsider—a foreign god from the East. Though conceived by (if not born from) a mortal woman, he was worshipped as a god. And while commonly numbered as one of the Twelve Olympians, he sometimes ceded his place to Hestia, the goddess of the hearth.[1]

Dionysus’ most recognizable role was as the god of wine and intoxication (as well as the related domains of vegetation and nature). The “god of abundant clusters,”[2] Dionysus embodied and ruled over wine in all its forms and uses—wine as an inspiration for music[3] and love,[4] or as relief from care[5] and old age,[6] but also as an instigator of madness[7] and violence.[8]

Dionysus was also the god of the soil more generally, and of the growth and ripening of vegetation.[9] Though he was first and foremost the god of the vine and its byproducts, Dionysus was also strongly connected with ivy, which frequently accompanied him in literature and art. He was also the god of laurel,[10] fir,[11] oak,[12] and sarsaparilla.[13]

In addition to discovering wine and viticulture, Dionysus was sometimes credited with other agricultural advances, including the discovery of the fig tree[14] and the apple tree,[15] or even the distillation of beer from barley.[16]

The Triumph of Bacchus by Diego Velázquez (ca. 1628–1629)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainAs the god of ritual madness and ecstasy, Dionysus brought madness (mania in Greek) to his worshippers. He was especially connected with women’s ritual ecstasy,[17] though married women were thought to achieve a closer communion with the god than unmarried girls.[18]

As a god of theater and the arts, Dionysus was associated in particular with music and dance. He was the god of drama, an art that evolved (according to Aristotle) from the dithyramb—the specific cult song of Dionysus.[19] Dionysus was also the god of the mask, which was prominent in cult and performance as a representation of Dionysus himself.

Dionysus’ role as a god of the dead and the afterlife was stressed above all in mystery cults. In this capacity, Dionysus offered rebirth and even deification. One early writer went so far as to identify Dionysus with Hades, the traditional lord of the dead.[20]

Attributes

Dionysus’ main attributes were, of course, related to wine and viticulture: vines, ivy, cups of wine, and so forth. The god was known to reveal himself to his human worshippers in various forms, both human and animal. He was, above all, an ambivalent god, “the most terrible and yet most mild to men.”[21] This was likely a reflection of the Greeks’ understanding that wine could bring both joy and suffering.[22]

The "Hope Dionysus," a 1st-century CE Roman copy after a Greek original of the 4th century BCE showing Dionysus leaning on a female figure; restored by Vincenzo Pacetti

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainLike most of the Greek gods, Dionysus was imagined as anthropomorphic (meaning he had the features of a human being). However, Dionysus could also be theriomorphic, sporting the features of various animals. He was especially connected with bulls, whose form he often assumed,[23] though he could also manifest as a young goat,[24] a ram,[25] a lion,[26] or a snake.[27]

Dionysus was remarkable for the variety of forms his appearance could take: he could be human or animal, young or old, bearded or beardless, feminine or masculine. Ancient writers and artists placed a particular emphasis on Dionysus’ hair, which was usually imagined as flowing and curly;[28] though sometimes described as dark,[29] it was more commonly blonde or tawny.[30]

Dionysus was typically represented wearing a chiton, a kind of tunic fastened at the shoulder, over which he wore a nebris—the skin of a fawn, kid, or leopard.[31] The god often sported a crown of foliage, vines, ivy, or other crops on his head, with his feet clad in high boots such as kothornos[32] or embas.[33]

Dionysus was usually shown holding his attributes, such as a branch of pine or fir, or a vine or ivy plant. His special rod was the thyrsus—a stem of narthex or fennel topped by a pinecone and foliage. Dionysus’ attributes also included all kinds of musical instruments, especially the tympanum, a kind of hand drum.

Dionysus was usually accompanied by his entourage (or thiasos) of frenzied worshippers. These were often headed by the maenads (also known as Bacchae, Bassarides, or Thyiades)—scantily clad female worshippers in a state of ritual ecstasy. In early sources, the maenads were sometimes worshipped as the infant Dionysus’ nurses.[34]

The god’s entourage also included other nymphs as well as satyrs or silens—joyful woodland creatures with a human torso and head, but with the ears, tail, and sometimes hind legs of a horse. Silenus, the eldest of the satyrs, was often described as the tutor of Dionysus (though this role was later assumed by Hermes).[35]

Attic black-figure neck-amphora showing Dionysus with satyrs and maenads (ca. 550–540 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainDionysus was also associated with other gods of nature, culture, and the arts, including the Charites (the Graces), the Muses, Pan, Apollo, Aphrodite, and Rhea (or her Phrygian counterpart Cybele).

Iconography

Dionysus appeared in ancient art more than any other Greek deity and was shown in connection with almost every type of myth, cult, and aspect of daily life.

The earliest depictions of Dionysus, from the sixth century BCE (or perhaps even earlier), showed the god with his attributes of wine and the amphora. During this period, Dionysus often had a full beard, but by the Classical period (479–323 BCE) he was increasingly represented as a beardless young man.

Macedonian mosaic showing Dionysus riding a leopard (fourth century BCE). Pella, Greece.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn both art and literature, Dionysus was typically depicted wearing a nebris (animal skin) and carrying a kantharos (drinking cup) or thyrsus. Sometimes he was shown riding atop wild cats, such as leopards, lions, and panthers, and was often accompanied by his entourage of satyrs, silens, maenads, and/or nymphs.[36]

Etymology

The name Dionysus (Greek Διόνυσος, translit. Diónysos; Homeric Greek Διώνυσος, translit. Diṓnysos, Aeolic Greek Ζόννυσος, translit. Zónnysos) was first recorded on Mycenaean tablets from the twelfth or thirteenth century BCE. Originally written in a script called Linear B (which predates the Greek alphabet), the name appears on these tablets as di-wo-nu-so.

There is no consensus as to the exact meaning of the god’s name, but most philologists believe the word is rooted in Dios, the possessive (genitive) form of the name “Zeus” (Dionysus’ father).

Bacchus by Simeon Solomon (1867)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe latter part of his name may be derived from Mount Nysa, where the infant Dionysus was thought to have been raised by nymphs, known as the Nysiads. Thus, when put together, “Dionysus” probably meant something like “the Zeus of Nysa” or “of Zeus and Nysa.”[37]

Other etymologies for Dionysus’ name have also been suggested, and scholars disagree on which is the most accurate. Robert Beekes, arguing that all attempts to trace the name to Indo-European languages have proven dubious, has suggested a pre-Greek origin.[38]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Dionysus Διόνυσος Phonetic

IPA

[dahy-uh-NAHY-suhs] /ˌdaɪ əˈnaɪ səs/

Other Names

As perhaps the most widely worshipped of all the Greek gods, Dionysus had a colorful array of alternative names. The best known of these is Bacchus (Greek Βάκχος, translit. Bákchos), the name often used in Roman literature. By the fourth century BCE, the Roman god Liber or Liber Pater was commonly identified with Dionysus and/or Bacchus.

Zagreus (Greek Ζαγρεύς, translit. Zagreús) sometimes appeared as another name for Dionysus (though he likely originated as a separate god). The name was especially connected with the Dionysus worshipped by the Orphics, a cult that believed a blissful afterlife could be attained through a combination of strict ritual and an ascetic lifestyle. Though the name Zagreus does not appear in any surviving Orphic texts, other ancient authors associated this name with Orphism.

Another obscure god, Iacchus (Greek Ἴακχος, translit. Iákchos), was often identified with Dionysus. Iacchus was more properly a god of the Eleusinian Mysteries, worshipped alongside Demeter and her daughter Kore (Persephone).

Finally, Dionysus was sometimes identified with Sabazius (Greek Σαβάζιος, translit. Sabázios), a sky and horse god worshipped by the Phrygians and Thracians.

Ivory and gold miniature of Sabazius from the tomb of Alexander IV at Aegae (311 BCE)

Mary HarrschCC BY-SA 4.0Titles and Epithets

Dionysus had many epithets and cult titles (also known as “epicleses”), reflecting his wide range of roles and powers.[39]

As a god of madness and ecstasy, Dionysus was given epithets such as μαινόμενος (mainómenos), “raving.” This aspect of the god seems to be behind his most familiar cult titles, including Βάκχος (Bákchos) and its variants Βακχεῖος (Bakcheîos) and Βακχεύς (Bakcheús), meaning “reveler,” as well as Βρόμιος (Brómios), meaning “roaring.”

Attic red-figure neck-amphora attributed to the Niobid Painter showing Dionysus and maenads at an altar (ca. 460–450 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAs a loosener of social norms, Dionysus was known as the “loosener,” rendered as λυαῖος (lyaîos) in Mantinea or λύσιος (lýsios) in Corinth and Sicyon. A similar title is Ἑλευθερεύς (Eleuthereús) or Ἐλευθέριος (Eleuthérios), meaning “liberator.”

Other regional titles focused on various aspects of the cult of Dionysus. He was ὠμάδιος (ōmádios) on Chios and ὠμηστής (ōmēstḗs) on Lesbos—the “eater of raw flesh.” This title reflected the custom in some cults of Dionysus of tearing apart animals and consuming them raw (omophagia).

Family

In the most familiar tradition, Dionysus was the son of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Semele, a mortal princess from Thebes.[40] Some sources, however, assigned him a different mother. In the mysteries, Dionysus’ mother was either Persephone[41] or Demeter,[42] while other traditions made his mother Aphrodite,[43] Arge[44] or Dione.[45]

Dionysus’ most famous relationship was with Ariadne, daughter of the Cretan king Minos. Dionysus fell in love with Ariadne after she was abandoned by Theseus on the island of Naxos.

He made her his wife, and in some accounts she was even immortalized so that she could live forever by his side.[46]

Dionysus had several children, though none of them achieved great cultural renown. His children by Ariadne included the Argonaut Staphylus[47] (and perhaps Phanus),[48] the Lemnian king Thoas,[49] and the Chian king Oenopion.[50]

Other traditions supplied further consorts and children for Dionysus. By Aphrodite, Dionysus was sometimes said to have fathered the vegetation god Priapus or even the love god Eros. By Althaea, wife of the Calydonian king Oeneus, he fathered Deianira.[51] By the nymph Nicaea, he fathered Telete, the personification of initiation.[52] And by Hera, he fathered the goddess Pasithea.[53]

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

Dionysus is one of the oldest Greek gods. His name first appeared in writing as early as the thirteenth century BCE, as attested by three tablets found in Pylos and Chania on the island of Crete. In the Linear B script—used to write an early form of the Greek language before the introduction of the Greek alphabet—the god’s name is given as di-wo-nu-so.

The Linear B tablets mentioning Dionysus clearly refer to him as a god; one of them even seems to connect him with wine. The tablet from Chania gives evidence for a joint cult of Zeus and Dionysus on Crete during the Bronze Age. Some scholars have also contended that Dionysus was worshipped at the early shrine of Ayia Irini on Ceos.

The cult of Dionysus was exceptionally widespread, with cult centers across both the Greek and non-Greek worlds. This diffusion, combined with the atypical elements of Dionysus’ mythology (the god’s double birth, his mortal mother, etc.), may have been part of the reason that the Greeks viewed Dionysus as a foreign god, despite the fact that he was known in Greece from such an early period.

Birth and Upbringing

The Double Birth of Dionysus

Though there were many different versions of Dionysus’ birth and parentage circulating in antiquity—so many versions, in fact, that some authorities claimed that there was more than one Dionysus—the most prevalent and widely known account made him the son of Zeus and the mortal princess Semele.

Semele was a beautiful daughter of Cadmus, the king and founder of Thebes. When Semele was already pregnant with the baby Dionysus, Zeus’ jealous wife Hera visited her in disguise (in one tradition, she assumed the form of Semele’s nurse Beroe). She convinced Semele to have her lover prove that he was really Zeus by appearing to her in the same glory with which he came to the bed of his wife Hera—knowing full well that no mortal could survive such an encounter.

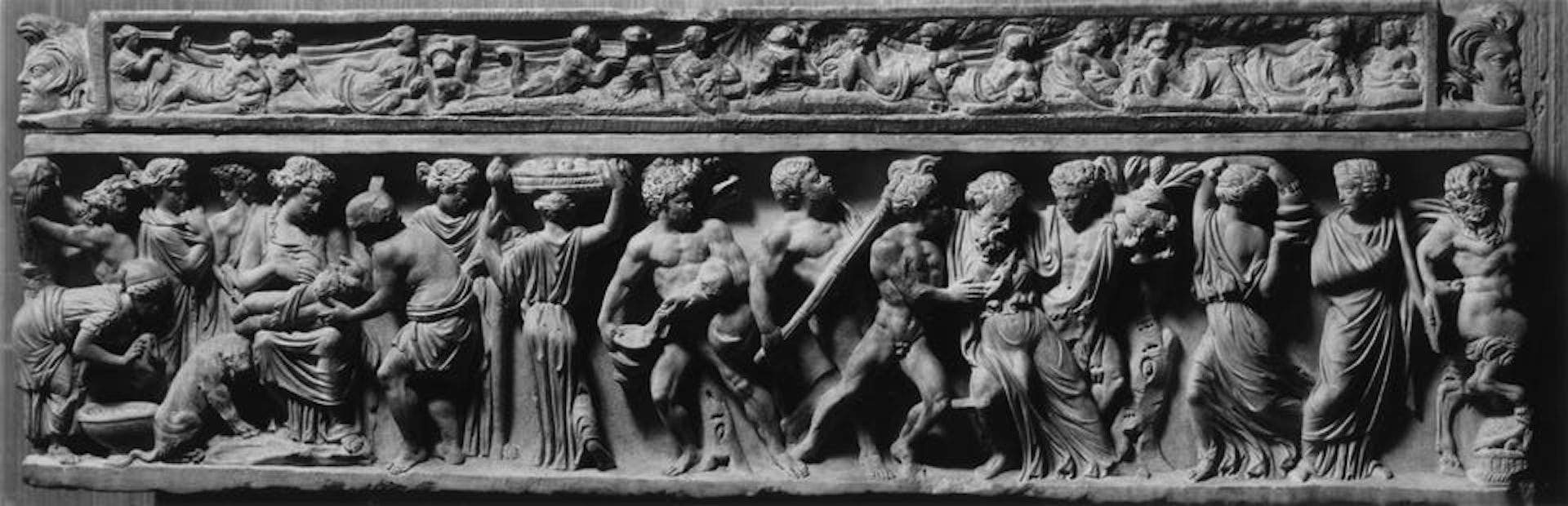

A Roman sarcophagus, dubbed the “Childhood Sarcophagus,” details the birth of Dionysus (nursed by a nymph, at left). The God of Wine is accompanied by his favorite animal, the panther, his future mentor, Silenus, and a host of attendants, satyrs and maenads (ca. 150–60 CE).

Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainSemele made Zeus swear an unbreakable oath to grant her whatever she asked. Thus, when she demanded to see Zeus undisguised, he had no choice but to give in. He revealed himself to Semele in all his divine glory: as blazing thunder and lightning. Ovid vividly imagines the scene in his Metamorphoses:

he sadly mounted to the lofty skies, and by his potent nod assembled there the deep clouds: and the rain began to pour, and thunder-bolts resounded. But he strove to mitigate his power, and armed him not with flames overwhelming as had put to flight his hundred-handed foe Typhoeus—flames too dreadful. Other thunder-bolts he took, forged by the Cyclops of a milder heat, with which insignia of his majesty, sad and reluctant, he appeared to her.[55]

The sight was too much for Semele (as Hera had known it would be), and she died of fright. But Zeus (in some versions with the help of Hermes) managed to save the unborn baby in Semele’s womb. Zeus sewed the child into his thigh until he reached maturity, which is how Dionysus came to be born twice: once from his mother Semele, and again from the thigh of his father Zeus.[56]

There were a number of variants of this myth of the double birth of Dionysus. In a Naxian version, Zeus seems to have killed Semele on purpose so that Dionysus could be born from him instead and thus become a god.[57]

In the town of Brasiae (or Prasiae) in Laconia, on the other hand, Semele actually survived long enough to give birth to Dionysus, but she and her infant son were locked in a chest and thrown into the sea shortly thereafter. By the time the chest drifted ashore at Brasiae, Semele was dead, but Dionysus survived and was brought up at the grotto of his Aunt Ino.[58]

The Infant Bacchus by Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1514)

National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., United States)Public DomainBirthplace

Ancient authors fiercely debated the exact location of Dionysus’ birthplace. This controversy was already raging by the sixth or fifth century BCE, as seen in the only surviving portion of the first Homeric Hymn:

For some say, at Dracanum; and some, on windy Icarus; and some, in Naxos, O Heaven-born, Insewn; and others by the deep-eddying river Alpheus that pregnant Semele bare you to Zeus the thunder-lover. And others yet, lord, say you were born in Thebes; but all these lie. The Father of men and gods gave you birth remote from men and secretly from white-armed Hera. There is a certain Nysa, a mountain most high and richly grown with woods, far off in Phoenice, near the streams of Aegyptus.[59]

Nysa—which had been associated with Dionysus since the time of the Homeric epics (eighth century BCE), and which was often regarded as the site of the god’s birth or upbringing—was located somewhere in the East. Ancient authors variously placed Nysa in Arabia, Babylon, Cilicia, Egypt, Erythra, Ethiopia, India, Libya, Lydia, Macedonia, Naxos, Thessaly, Thrace, or Syria.[60]

Other authors, however, insisted that Dionysus had been born elsewhere, whether in his mother Semele’s homeland of Thebes or in Naxos, Dracanum, or Crete.[61] Much later, the poet Oppian claimed that Dionysus was born either on Mount Meros in India or in the Cave of Aristaeus in Euboea.[62]

Upbringing

Early traditions claimed that Dionysus was taken to Mount Nysa as an infant, either by Hermes[63] or by Zeus himself (as was sometimes depicted in art).[64] There he was raised by nymphs, though the exact identities and names of Dionysus’ nurses varied across ancient sources.

According to the early mythographer Pherecydes, Dionysus’ nurses were the seven Hyades—nymphs associated with the celestial realm[65]—while Panyassis wrote that he was nursed by the nymph Thyone.[66] In one account, Dionysus’ nurse was the nymph Macris, whom Hera expelled from her home on the island of Euboea as punishment for bringing up her enemy;[67] according to others, the nurse’s name was Nysa;[68] and another tradition named several nurses: Philia, Coronis, and Cleis.[69]

Roman fresco from a house in the neighborhood of the Villa Farnesina showing the upbringing of Dionysus (Bacchus) (ca. 20 CE)

Roman National Museum, RomePublic DomainDionysus was very close to his nurses. In some traditions, he even rewarded them later by restoring their youth or by transforming them into the Hyades and placing them in the sky.[70]

But in another familiar tradition, Dionysus was brought up by his mother’s sister Ino and her husband Athamas. Some authors reconciled the two versions of Dionysus’ upbringing by saying that Dionysus was brought to Ino after the nymphs became afraid of Hera’s anger,[71] though others said that Ino and Athamas raised Dionysus before he came to the nymphs.[72]

Sadly, Dionysus was not destined to lead a carefree childhood with his aunt and uncle. The indefatigable Hera targeted Ino and Athamas in her anger, driving them into a state of homicidal madness: Athamas killed one of his sons, while Ino leapt from a cliff into the sea with another son. Ino later became the goddess Leucothea (in some traditions, it was Dionysus himself who turned her into the goddess).[73]

Ino and Melicertes by Pierre Granier (17th century)

Parc du Versailles / Luis Miguel Bugallo SánchezCC BY-SA 4.0The Travels of Dionysus

After Hera destroyed Dionysus’ guardians, she turned her attention to Dionysus himself. It was often said that the notoriously vengeful goddess drove her husband’s illegitimate son mad, causing him to wander the world in a raving state. According to the lost epic Europea, Dionysus wandered until he came to Phrygia, where Rhea (or Cybele, with whom Rhea was commonly identified) cured his madness and taught him her rites.[74]

After he was cured and purified, Dionysus continued east to India. He traversed the vast subcontinent before finally setting up pillars at the edge of the earth.[75]

The narrative of Dionysus’ adventures in India was further developed by the fifth-century CE poet Nonnus in his massive epic the Dionysiaca. The Dionysiaca describes how Dionysus and his band of revelers were met with hostility by the powerful Indian king Deriades. But Dionysus, with the help of his satyrs, silenes, and maenads, was able to conquer the Indians after a long war. He then taught his former enemies about wine and worship of the gods, founded several cities, and set up pillars and monuments in his own honor.

The Triumph of Bacchus by Cornelis de Vos (seventeenth century).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainDionysus as the God of Wine

The Discovery of the Vine

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca relates a curious account of how the young Dionysus discovered wine. The adolescent Dionysus loved a satyr named Ampelus, though he knew that his lover was destined to die. Sure enough, Ampelus was soon killed in a bull-riding accident. Shortly thereafter, his body was transformed into a vine (in Greek, the word for “vine” is ampelos), and the heartbroken Dionysus made wine for the first time.[76]

In an alternative version, also recorded by Nonnus, the vine already existed long before Ampelus’ demise. However, its secrets remained undiscovered until Dionysus noticed a snake sucking the juice from the grapes. Based on this observation, Dionysus invented wine, and he and his satyrs celebrated the first harvest dead drunk.[77] Nonnus paints a colorful picture of this frenzied scene:

The wine spurted up in the grapefilled hollow, the runlets were empurpled; pressed by the alternating tread the fruit bubbled out red juice with white foam. They scooped it up with oxhorns, instead of cups which had not yet been seen, so that ever after the cup of mixed wine took this divine name of Winehorn.[78]

Bacchus and Ampelus by Francesco Righetti (1782)

RijksmuseumCC0Icarius

In another important myth, Dionysus taught the art of winemaking to the farmer Icarius, who offered the god hospitality when he came to Attica. Icarius introduced the new beverage to his neighbors. Unfortunately, upon experiencing drunkenness for the first time, Icarius’ neighbors thought they had been poisoned and angrily killed Icarius.

The next day, Icarius’ neighbors—now sober—realized what they had done. They tried to bury Icarius in secret, but the body was discovered by Icarius’ daughter Erigone and her dog Maera. Erigone was so devastated that she hanged herself.

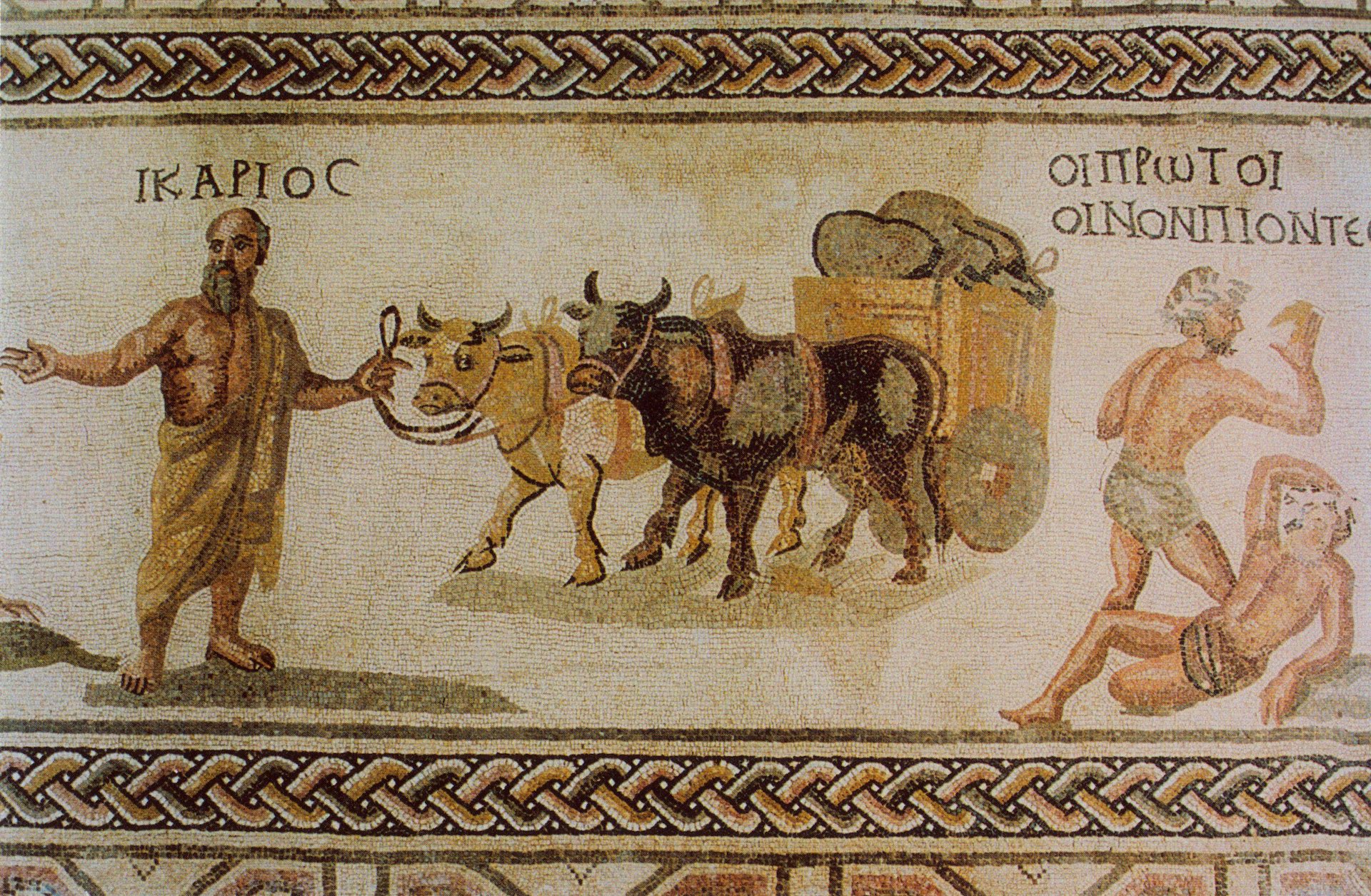

A Roman-era mosaic from the House of Dionysus in Paphos (Cyprus) showing Iacrius (left) with his cattle (third century CE)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainWhen Dionysus learned of the fate of Icarius and Erigone, he was furious. He punished Attica by driving all the unmarried women mad so that they hanged themselves just as Erigone had. Only when the people of Attica granted cult honors to Icarius and Erigone did Dionysus relent. Icarius was then placed in the stars as the constellation Bootes.[79]

Other Disciples of Dionysus

In addition to the ill-fated Icarius, there were other mortals who were taught viticulture by Dionysus.

In one tradition, the first man to receive the vine from Dionysus was Oeneus, the king of Calydon (one source added that Dionysus traded the vine for a night with Oeneus’ wife Althaea).[80]

In an alternative version, Oeneus’ herdsman Staphylus was the first to notice that when his master’s goats ate the fruit of the vine, they became unusually frisky. When Staphylus took this information to Oeneus, Oeneus made a drink from the fruit and gave some to Dionysus. Dionysus was pleased and therefore taught Oeneus how to cultivate the vine. He named the drink after Oeneus (the Greek word for “wine” is oinos) and the plant after Staphylus (the Greek word for “grape cluster” is staphylos).[81]

In Athens, it was said that Dionysus taught the early king Amphictyon how to mix wine with water in the right proportions.[82] Another king, Oenopion of Chios, learned viticulture from Dionysus (who also happened to be his father).[83]

Finally, Dionysus gave special powers to Spermo, Elais, and Oeno, the daughters of the Delian king Anius. These sisters were able to produce grain, oil, and wine from mere earth and water (Spermo produced grain, Elais oil, and Oeno wine). During the Trojan War, the sisters accompanied the Greeks to Troy, where they were a great asset to the army during the decade-long conflict.[84]

Dionysus, Olympus, and the Return of Hephaestus

Dionysus’ role on Mount Olympus was not unlike his role on earth: among the gods he represented wine, intoxication, and merriment. The story of Dionysus and Hephaestus illustrates this well. Shortly after Hephaestus’ birth, he was expelled from Mount Olympus by his own mother, Hera, who was repulsed by his malformed feet.

Seeking revenge, Hephaestus devised a trap for his mother: a chair with a hidden mechanism that ensnared Hera once she sat in it. Anxious to free her and restore order among the Olympian deities, the gods tried everything to coax Hephaestus back to Olympus.

But Hephaestus could not be swayed—that is, until Dionysus approached him and made him drunk. Now in a more amenable mood, Hephaestus allowed Dionysus to return him to Olympus (in ancient vase paintings, Dionysus is usually depicted leading Hephaestus on the back of a mule). Hephaestus freed Hera at last, and in some traditions Hera was so grateful to Dionysus that she made him one of the Olympian gods.[85]

Athenian black-figure plate depicting Hephaestus on the back of Dionysus’s donkey (date unknown). This famous comedic scene was often displayed on pottery made in Attica and Corinth.

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainDionysus’ Descent to the Underworld

As the mother of Dionysus—one of the most important Greek gods—Semele was commonly said to have been deified after her death, living on Mount Olympus with her son and the other immortal gods.[86]

But in many traditions, Dionysus first needed to descend to the Underworld to retrieve his mother. Extant sources do not tell us much about Dionysus’ journey; we learn only that Dionysus descended to the Underworld, found Semele, and brought her back with him to Olympus, where she became a goddess. In some accounts, she was even given a new name: Thyone.[87]

The Wrath of Dionysus

Throughout his travels, Dionysus spread knowledge of the sacred vine, and with it knowledge of his worship. However, he was not always peacefully welcomed. When Dionysus was opposed, his anger was severe—as illustrated by many of the god’s most famous myths.

Lycurgus

When Dionysus introduced his cult in Thrace, he was met with resistance from Lycurgus, the king of the Edonians. In one early tradition, Lycurgus attacked Dionysus’ band of followers, and Dionysus was only able to escape by leaping into the sea and taking refuge with the kindly sea goddess Thetis (who later became the mother of Achilles).[88]

Roman mosaic from Herculaneum showing Lycurgus fighting Ambrosia and Dionysus (first century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / AmphipolisCC BY-SA 2.0There are different versions of how Lycurgus was punished for his opposition. In the earliest account, transmitted in Homer’s Iliad, Lycurgus was blinded by Zeus and died soon after.[89] But in most subsequent accounts, it was Dionysus himself who punished Lycurgus, usually with some form of madness that caused the Thracian king to kill various members of his family or even harm himself.[90]

Pentheus

When Dionysus finally returned to Thebes, the homeland of his dead mother Semele, many refused to worship him or believe he was the son of Zeus. As he had in Thrace and India, Dionysus set out to prove his divinity in no uncertain terms. He infected the Theban women with his divine ecstasy and drove them to celebrate his rites in the mountains.

Pentheus, the king of Thebes (and Dionysus’ cousin), followed the women to the mountain to try and stop them. But his own mother, Agave—in her Dionysian intoxication—mistook Pentheus for an animal and, together with the maenads, tore him apart with her bare hands.

This gory story is told in detail in Euripides’ final tragedy, the Bacchae. At the end of the play, Agave recovers her sanity and realizes with horror what she has done. Dionysus reveals himself as a god, explains why he punished Pentheus and Agave, and metes out further punishments to the rest of the Theban royal family for their failure to honor him properly (in particular, he turns Pentheus’ grandparents, Cadmus and Harmonia, into snakes).[91]

Attic red-figure lekanis lid showing the death of Pentheus (ca. 450–425 BCE)

Louvre, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainThe Minyades

Another myth set in Boeotia describes Dionysus’ confrontation with the Minyades, the daughters of King Minyas of Orchomenus. These Minyades (whose names were usually given as Alcathoe, Arsippe, and Leucippe) were very diligent in observing their domestic duties. As they spent their days weaving, they condemned the women who abandoned their duties to take part in the rites of Dionysus.

The Minyades’ indifference to his cult upset Dionysus; in some traditions, he even approached them in disguise to try to convince them of the error of their ways, but to no avail. In the end, Dionysus punished the Minyades by causing vines, ivy, or milk to emerge from their looms, and by transforming the sisters into birds or bats. In some versions, Dionysus also drove the Minyades into a frenzy that led them to tear apart and devour Leucippe’s son.[92]

The Daughters of Minyas by Jean Lepautre (1676)

National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., United States)CC0The Proetides

Similar to the Minyades, the Proetides—daughters of the Argive king Proetus—spurned the worship of Dionysus and were punished for it (though in an alternative tradition, the Proetides were punished by Hera for a completely different reason).

The Proetides, like so many of Dionysus’ enemies, were driven mad by the god. But their myth had a happy ending, for they were eventually cured by the holy man Melampus.[93]

The Tyrrhenian Pirates

Another famous myth told of how Dionysus was abducted by sailors or pirates.

The seventh Homeric Hymn—the Hymn to Dionysus—is the earliest and possibly best-known source for this myth. It describes how Dionysus was snatched one day by Tyrrhenian pirates, who were awestruck by his beauty and wished to sell him for a high price (in other versions, Dionysus had hired the ship to take him to a specific destination, usually given as the island of Naxos, and was kidnapped on the way).

Only the helmsman (called Acoetes in later texts) sensed that the beautiful youth was no ordinary human, but his attempts to convince the pirates to let Dionysus go were in vain.

After the helmsman’s warnings went unheeded, Dionysus proved that he was more than capable of taking care of himself. He soon caused the pirates to start seeing strange things:

First of all sweet, fragrant wine ran streaming throughout all the black ship and a heavenly smell arose, so that all the seamen were seized with amazement when they saw it. And all at once a vine spread out both ways along the top of the sail with many clusters hanging down from it, and a dark ivy-plant twined about the mast, blossoming with flowers, and with rich berries growing on it; and all the thole-pins were covered with garlands…

But the god changed into a dreadful lion there on the ship, in the bows, and roared loudly: amidships also he showed his wonders and created a shaggy bear which stood up ravening, while on the forepeak was the lion glaring fiercely with scowling brows.[94]

In terror, the pirates leapt into the sea, where they were promptly transformed into dolphins. But Dionysus spared the helmsman, who had tried to help him (in some later traditions, it was said that the helmsman became a fervent follower of Dionysus).[95]

The Dionysus Cup by Exekias (ca. 530 BCE), showing Dionysus sailing in a ship with dolphins

MatthiasKabelCC BY-SA 3.0Other Myths of the Wrath of Dionysus

There were a number of lesser-known myths illustrating Dionysus’ wrath against his enemies. These tended to follow a similar pattern as the more famous myths of Pentheus, Lycurgus, and the like, with a specific mortal or community failing to acknowledge the divinity of Dionysus and subsequently learning the error of their ways through a terrible punishment (usually involving madness).

In several myths, Dionysus struggled with the people of Argos. According to one story, he drove the Proetides and the other women of Argos mad when they failed to observe his rites (see above). In another story, mentioned very briefly by Ovid, the Argive king Acrisius (the grandfather of Perseus) shut the god out of his city and was punished for it (we are not told what his punishment was).[96]

Yet another story told of how Acrisius’ grandson Perseus fought Dionysus in battle, killing many of the god’s maenads before making peace with him and introducing Dionysus’ cult to Argos.[97]

Perseus with the Head of Medusa by Antonio Canova (1804–1806)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThere were other, more obscure myths of how Dionysus punished local communities that spurned him. In the city of Eleutherae (on the border between Attica and Boeotia), it was said that Dionysus sent a vision of himself wearing a black goatskin to the daughters of Eleuther (the eponymous founder of the city) as they slept.

When the girls mocked this vision, Dionysus was so furious that he drove them mad. Only when Eleuther established a new cult of Dionysus Melanaigis (“Dionysus of the Black Goatskin”) did the god free the girls of their madness.[98]

There was also a myth telling of how the Athenians once failed to worship Dionysus. Their punishment, it was said, was “priapism” (probably a term for erectile dysfunction).[99]

In some myths, Dionysus turned his wrath against specific individuals. For example, he was sometimes said to have turned against the musician Orpheus, who had hailed Apollo or Helios as the greatest god instead of Dionysus. To teach him a lesson, Dionysus sent the Bassarides—frenzied female worshippers of his—to tear Orpheus apart.[100]

Another mythical figure, the Mysian king Telephus, was said by some authorities to have angered Dionysus by neglecting his worship. According to this tradition, the spurned Dionysus caused Telephus to trip on a grapevine as he was running away from Achilles, allowing Achilles to overtake and seriously injure his opponent.[101]

Ariadne

The most famous of Dionysus’ consorts was Ariadne, who played an important role in the Theseus myth. A daughter of King Minos of Crete, it was Ariadne who helped Theseus navigate the Labyrinth and slay the Minotaur. She then ran away with Theseus, hoping to become his wife in his homeland of Athens. But Theseus (either deliberately or accidentally) left Ariadne on Naxos, one of the Aegean Islands.

Dionysus happened to be roaming the Aegean at this time and noticed the abandoned and despairing Ariadne on Naxos. He immediately fell in love with the beautiful maiden and made her his wife, presenting her with a beautiful golden crown.[102] They had several sons together (see above).

Bacchus and Ariadne by Antoine-Jean Gros (ca. 1822).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThere were different versions of Ariadne’s ultimate fate. According to Hesiod, Dionysus brought Ariadne with him to Olympus and had Zeus make her immortal.[103] Homer, on the other hand, writes obscurely that Ariadne was killed by Artemis in a place called Dia.[104] Nonnus tells us that Ariadne was killed during Dionysus’ war with Perseus: she was turned to stone when she looked upon Medusa’s head.[105]

Other Myths

There are many further myths about Dionysus—too many to record them all here. Nonetheless, certain patterns and trends can be identified across these myths.

Some of Dionysus’ myths dealt with his martial exploits. In the Gigantomachy—the war between the gods and the monstrous Giants—Dionysus fought beside the other gods and killed the Giant Eurytus with his thyrsus.[106] In some traditions, Dionysus even seems to have taken part in the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympian gods and the Titans (though this conflict was more commonly said to have taken place before he was born).[107]

In a local Argive myth, Dionysus invaded Argos during the reign of Perseus, leading an army of female worshippers from the Greek islands. But Perseus was able to defend his city against Dionysus’ onslaught, killing most of the women. He and Dionysus then made peace, and Dionysus even made arrangements for his beloved Ariadne to be buried in Argos after she died.[108]

In other myths, Dionysus battled exotic mythical creatures. One Tanagran myth told of how the women of the city were attacked by a Triton one day while bathing in the sea. They invoked the help of Dionysus, who emerged to kill the Triton. In another version of the myth, however, the Tanagrans took care of the Triton themselves by leaving a bowl of wine on the shore, which caused him to fall into a drunken slumber. They then chopped off the offending creature’s head.[109]

A Nereid riding a triton, from the southwest medallion of the Deities Mosaic (2nd century CE)

Villa of Orbe-Boscéaz, Vaun / Mary HarrschCC BY-SA 4.0Dionysus also played a role in one version of the myth of Agdistis—a Phrygian deity who was born a hermaphrodite. The other gods feared that Agdistis would be too powerful because they possessed both male and female reproductive organs; thus, they sent Dionysus to castrate Agdistis.[110]

Other myths centered on Dionysus’ entourage. One story, attested only in later antiquity, tells of how Dionysus’ mentor Silenus became inebriated and wandered off, only to find himself in the garden of the great King Midas. The king welcomed Silenus to his court, where he was wined and dined for days. When Midas at last returned Silenus, Dionysus offered the king anything his heart desired as a reward. Midas foolishly wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. Thus, the king acquired his infamous Midas touch from Dionysus.[111]

There were also additional myths about Dionysus’ interactions with the other gods. In one of the origin myths of Naxos, it was said that Dionysus and Poseidon competed over which of them would be the chief god of the island. Poseidon lost, and so Naxos became the island of Dionysus.[112]

Dionysus was also connected with Hymenaeus, the god of marriage. Some sources even made Hymenaeus the son of Dionysus.[113] In an alternative tradition, Hymenaeus was a mortal singer who died while performing at the wedding feast of Dionysus and Ariadne.[114]

Attic black-figure neck amphora by the Circle of the Antimenes Painter (ca. 520 BCE) showing Dionysus (center) accompanying Hephaestus riding a donkey (right) as a maenad looks on (left)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0Alternative Mythologies

In addition to the common mythology (outlined above), there were many other conceptions of Dionysus in the ancient world. For example, the early philosopher Heraclitus (ca. 535–474 BCE) claimed that Dionysus and Hades were one and the same.[115] Others associated Dionysus with the Egyptian god Osiris.[116] These diverse interpretations had an immense effect on how Dionysus was worshipped, leading to multiple alternative mythologies of the god.

Orphism

Orphism was a mystical religion based on poems attributed to Orpheus, which emphasized purification and renewal through ritual. Little is known of their cult, since initiated Orphics were prohibited from revealing important ritual information to the uninitiated. However, a few tantalizing slivers of evidence do allow us to reconstruct the outlines of the Orphic myth of Dionysus.

First, the Orphic Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Persephone, not Semele. He was born after Zeus seduced Persephone in the form of a serpent. This Dionysus, usually depicted as horned, was raised in the mountains, where he discovered wine in his youth.

One day, the Titans killed the boy and tore him apart. Zeus, seeing what the Titans had done, struck them dead with his thunderbolt, and humans were created from the ashes. In some accounts, it seems Dionysus was resurrected soon after.[117]

This form of Dionysus is identified by many modern sources with a god called Zagreus (though Diodorus called him Sabazius). However, followers of Orphism seem to have simply called their god Dionysus.[118]

The Eleusinian Mysteries

A closely related alternative to the Orphic Dionysus was the Eleusinian Dionysus. This version of the god of intoxication was identified with Iacchus (possibly because of the similarity between the name Iacchus and Dionysus’ common alternate name Bacchus).

Photo showing a view of the excavation of Eleusis, Greece. This is the site of the annual Eleusinian Mysteries and an early temple to Demeter and Persephone, built around the 7th century BCE.

Marcus CyronCC BY-SA 2.0The Eleusinian Dionysus/Iacchus was the son of Zeus and either Persephone or Demeter (Persephone’s mother).[119] He may have also been the consort of Demeter.[120] Otherwise, his mythology was very similar to that of the Orphic Dionysus: as a boy he discovered wine, was attacked and murdered by the Titans, and was resurrected. Iacchus seems to have played a key role in the rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries (though, sadly, little else is known of him).

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

On Naxos one can still see the remains of an especially ancient sanctuary of Dionysus. The site was probably in use as early as the fifteenth or fourteenth century BCE, but the temple whose columns are still standing today dates from around the sixth century BCE. There were also many temples of Dionysus in the region of Boeotia, where the god’s mother Semele lived.

Remains of the Temple of Dionysus in Yria on the island of Naxos (sixth century BCE).

Olaf Tausch / Wikimedia CommonsCC BY 3.0In Athens, there was a temple of Dionysus connected with the theater complex at which the god was honored a few times per year. This temple was said to have been quite ancient and included paintings of various scenes from Dionysus’ mythology.[121]

In Argos, there was also a temple of Dionysus that was said to be very ancient. The Argives claimed that Dionysus buried his beloved Ariadne near this temple after she was killed by Perseus. The cult image inside was thought to have been there since the time of the Trojan War.[122]

During the Hellenistic and Imperial Roman periods, associations or colleges of Dionysus became larger and more important (examples include the Lobakchoi of Athens, the Bakchiastai of Cos and Thera, and the Bakcheastai of Dionysopolis). As a result, Dionysus became one of the most widely worshipped gods of the ancient Mediterranean.

Festivals and Rituals

Dionysus was honored with many festivals across many different cities and regions. Some of these were annual, but others were only celebrated every third year (e.g., Dionysus’ festivals at Delphi, Thebes, Camirus, Rhodus, Miletus, and Pergamum).

The Dance of the Bacchantes by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre (1849)

Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, LausannePublic DomainThe festivals and rituals of Dionysus were characterized by licentiousness, revelry, and the reversal of social roles. The most famous of these festivals were orgia (“orgies”)—riotous rituals that included dancing, singing, intoxication, and sacrifice. These events could be so raucous that some ancient cities and regions (including Attica) prohibited their practice.

Another important component of Dionysus’ cult was the phallic procession, a long procession of worshippers who marched behind a large sculpted phallus.

Dionysus was sometimes said to have received human sacrifices,[123] but there is no concrete evidence for this. Even if Dionysus did receive human sacrifice at some early stage in his worship, this custom almost certainly came to an end by the Classical period and was replaced with more traditional animal sacrifice.

Animals commonly sacrificed to Dionysus included pigs, sheep, and goats; goats and rams became particularly associated with the cult of Dionysus.[124] The god also received non-meat sacrifices such as produce, gifts, and cakes.

The Theater of Dionysus on the southern slope of the Acropolis in Athens

dronepicrCC BY 2.0Some of the festivals honoring Dionysus were more “family friendly” than the orgia. In Athens, the most famous annual festival of Dionysus was the Great Dionysia (sometimes called the City Dionysia). This fantastic, multiday celebration included processions, sacrifices, and theatrical performances; it was here that many of the most famous plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes were originally performed.

Other Dionysus festivals in Athens included the Lenaea, another dramatic festival; the Rural Dionysia,[125] whose central events were a phallic procession and contests; and the Anthesteria, called the oldest Dionysia, a kind of day of the dead in which the souls of those who had died were said to rise from the Underworld and wander the world of the living.

The Athenians also celebrated Dionysus at the Oschophoria (held after the conclusion of the grape harvest), the Theionia, and the Iobakcheia, though much less is known about these festivals.

The Triumph of Bacchus by Charles de la Fosse (1700/1701)

LouvrePublic DomainOther rituals of Dionysus were connected with death (like the Athenian Anthesteria). In Argos, for example, Dionysus was summoned from the water by throwing a lamp into an abyss for Hades and then blowing on a trumpet concealed in thyrsi.[126] The Delphians even displayed a tomb of Dionysus.[127]

Dionysus was a major god in ancient Greek mystery religions—religions that required initiation and forbade initiates from revealing their rites to the uninitiated. The Dionysian Mysteries were not limited to a particular geographic location; rather, they were organized by private communities of followers, made up of both men and women.[128]

Fueled by wine, music, and dance, the Dionysian Mysteries brought worshippers together in frenzied, orgiastic celebrations that freed them from social inhibitions. Many revelers wore masks to disguise themselves, and it was said that Dionysus himself would often appear among the throngs. These mysteries seem to have promised their initiates rebirth and even deification rather than a blessed afterlife.

Dionysus also played a central role in other mystery cults, such as the Orphic and Eleusinian Mysteries (whose respective mythologies have been outlined above).

Foreign Cults

In antiquity, Dionysus was often identified with the gods of foreign peoples, a practice sometimes known as interpretatio Graeca (literally, “translation into Greek”). Dionysus was thus conflated with gods such as the Etruscan Fufluns, the Egyptian Osiris or Epaphus-Horus, and, of course, the Italian Liber or Liber Pater.

Bacchus by Caravaggio (ca. 1598)

Uffizi Gallery, FlorencePublic DomainIn Rome, the mysteries of Dionysus were immensely controversial. Imported from Greece, the god’s rites—known in Rome as the Bacchanalia—involved intoxication and omophagy (the eating of raw meat). By the early second century BCE, these Bacchanalia had become so out of control that they were largely banned by the government.[129] This highlights the extreme effect that Dionysus could have on his devotees.

Popular Culture

Dionysus makes regular appearances in contemporary popular culture, often alongside the rest of the Olympic pantheon. He has appeared in countless retellings and reimaginings of Greek myth, from Disney’s Hercules, to the Hercules and Xena: Warrior Princess television series, to Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians books and films. In these media appearances, Dionysus is almost always depicted as a wine-besotted pleasure seeker.

Because wine is so heavily associated with Dionysus, the god has also lent his name to myriad wineries, from Greece to Napa Valley.