Apollo

The Birth of Apollo and Diana by Marcantonio Franceschini (ca. 1692–1709)

Liechtenstein Museum, ViennaPublic DomainOverview

Apollo was a powerful Greek god and one of the Twelve Olympians. He served as the divine patron of prophecy, healing, art, and culture, as well as the embodiment of masculine beauty.

Apollo belonged to the second generation of Olympians, along with his twin sister Artemis, goddess of the wild and hunting. He was commonly represented as a kouros—that is, as a young, beardless male. In ancient art, he could be seen carrying a lyre or a bow and arrow.

Key Facts

Who were Apollo’s parents?

Apollo was the son of Zeus, the supreme god of the Greek pantheon, and Leto, a descendant of the Titans. In myth, he and his twin sister Artemis were born on the island of Delos, the only place on earth that would give Leto shelter when Hera, Zeus’ jealous wife, sought to prevent her from giving birth. Apollo rewarded the island by making it one of the centers of his worship.

The Apollo Belvedere (ca. 120–140 CE)

Vatican Museums / Dennis JarvisPublic DomainWhat were Apollo’s attributes?

Apollo was usually viewed as the prototypical beautiful young man (kouros in Greek). He was distinguished by various symbols of his roles and powers, including the bow, lyre, and cithara, and was often depicted wearing a laurel wreath. Apollo’s sacred animals included the raven and the wolf.

The "Terrace of the Lions" at Delos, a gift from the Naxians (ca. 620–600 BCE)

ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0How was Apollo worshipped?

Apollo was widely worshipped with sanctuaries and festivals. His oracle at Delphi was one of the most influential in the Greek world. Apollo also had a major sanctuary on the tiny island of Delos, where he was said to have been born.

Like the other Olympian gods, Apollo had a rich temple cult and was honored with regular festivals throughout the Greek world, including the Pythian Games at Delphi. He was also worshipped in connection with aspects of everyday life, such as health and medicine. Ritual invocations called paeans were sung to Apollo in various contexts.

Apollo Killing the Python by Hendrik Goltzius (published 1589)

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainApollo and Python

According to one myth, while the young Apollo was establishing his oracle at Delphi, he encountered a monstrous serpent or dragon called Python. After a violent battle, Apollo won the upper hand and slew Python with his arrows. He then built his oracle over the corpse of his defeated enemy. Henceforth, the priestess of Apollo at Delphi was known as the “Pythia” to commemorate the god’s victory.

[FIGURE FOUR]

Etymology

As with most Greek deities, the etymology of the name “Apollo” has mysterious origins. It does not appear in the Linear B tablets, the earliest surviving texts of Greek civilization, written in a syllabic script during the Greek Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1100 BCE). However, this does not necessarily mean that Apollo was a late addition to the Greek pantheon: the name Paean, one of Apollo’s most common alternate names, does show up in Linear B.

Some scholars have posited that the name “Apollo” is a derivation from apella, a word in the Doric dialect of ancient Greek that means “public assembly.” Indeed, the Doric form of the god’s name is “Apellon.” In this interpretation, "Apollo” translates to “he who assembles” or “he of the assembly,” possibly referring to his reputation as the bringer of civilized order and the source of civil constitutions.[1]

Gregory Nagy, on the other hand, has argued that “Apollo” was derived from the words apeilē, a noun meaning “promise, boast, or threat,” and apeilein, a verb meaning “to make a promise, boast, or threat.” Such an etymology would render Apollo “the god of authoritative speech, the one who presides over all manner of speech-acts, including the realms of songmaking in general and poetry in particular.”[2]

Other Names

Apollo was often called “Paean,” a name that emphasized his ritual function as a god of healing and protection. This was a very ancient name—perhaps even more ancient than the name Apollo.

Another alternative name for Apollo was Phoebus, one of the god’s most popular epithets. Many ancient sources call the god “Phoebus Apollo” or even just “Phoebus.” The Romans, for example, referred to the god as “Phoebus” at least as often as they referred to him as “Apollo.”

Other names commonly used to identify Apollo include “Loxias” (referring to the god’s ambiguous oracles, called loxia) and “Lyceus” (a word that simultaneously evokes light, wolves, and the region of Lycia).

Epithets

Apollo’s diverse functions were reflected in his many epithets. In addition to titles such as Paean, Phoebus, Loxias, and Lyceus, which sometimes served as alternative names for the god (see above), Apollo was also called hekēbolos (“far-shooter”), hekaergos (“far-worker”), epikourios (“assisting”), oulious (“healer”), loimios (“pestilential”), and alexikakos (“ill-deterring”).

Other epithets, such as Dēlios (“Delian”), Pythios (“Pythian”), and Smintheus (“Sminthian”) refer to sites and places of worship considered sacred to Apollo.[6]

Attributes

Domains

As a god, Apollo was associated primarily with prophecy, music, and all things beautiful. But he was also regarded as the god of medicine and plague, livestock, colonization, and virtue.

Apollo was viewed as the symbol of universal and aesthetic order, civilization, and reason. In this capacity, he would punish the wicked and overbearing.

In the arts, Apollo stood for harmony and order, while Dionysus, the other divine patron of the arts, reveled in ecstasy and chaos. This led to the pairing of the “Apollonian” and “Dionysian” as the two opposing poles of artistic creation (an opposition made especially famous by the nineteenth-century German philosopher and philologist Friedrich Nietzsche).[7]

Iconography and Symbols

From earliest antiquity, Apollo was represented in both art and literature as eternally youthful and handsome, with locks of radiant hair, a clean-shaven face, and an athletic but not overly muscular physique. The god was most commonly identified by either a bow or a musical instrument (usually a lyre, but sometimes a more specialized stringed instrument called a cithara).

Apollo’s symbols were many. In addition to the bow, lyre, and cithara, Apollo was also represented by the tripod, a tall, three-footed structure (sometimes elaborately decorated) used for sacrifices and religious rituals. This object represented Apollo in his function as god of prophecy. The “Delphic tripod” was the famous tripod on which Apollo’s priestesses at Delphi sat and delivered the god’s prophecies.

Apollo’s symbols also included sacred plants, such as the palm tree (the tree under which he was usually said to have been born), the laurel (whose leaves crowned those honored by Apollo), and the cypress.

Finally, Apollo’s symbols included an array of sacred animals. Among the most important of these were swans and cicadas (symbolizing music and song); ravens, hawks, and crows (his messengers); snakes (connected with prophecy); and wolves, dolphins, deer, mice, and griffins.

Family

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

The mythology of Apollo began with his remarkable birth from the union of Zeus and Leto (the daughter of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe). Leto became pregnant by Zeus with twins while he was married to Hera. When Hera discovered this, she did everything in her power to try to prevent Leto from giving birth. According to the third-century BCE poet Callimachus, Hera even sent her son Ares to threaten any person or city that received Leto with utter destruction.[14]

In the end, Leto arrived on Delos, a tiny, barren island in the Aegean Sea. According to some sources, it was Apollo himself, whispering to his mother from inside the womb, who told Leto to seek shelter on this island.[15] Desperate to find relief from her labor pains, Leto addressed the island, begging it to let her give birth there and promising that if she were granted this kindness, Apollo would someday build a great temple on the seemingly unimpressive island:

for no other will touch you, as you will find: and I think you will never be rich in oxen and sheep, nor bear vintage nor yet produce plants abundantly. But if you have the temple of far-shooting Apollo, all men will bring you hecatombs and gather here, and incessant savour of rich sacrifice will always arise, and you will feed those who dwell in you from the hand of strangers; for truly your own soil is not rich.[16]

Delos, knowing that it had no natural gifts to offer, joyfully agreed to Leto’s terms. Thus, Leto gave birth to the twins Apollo and Artemis on the island, and in return Delos became one of Apollo’s sacred sites.

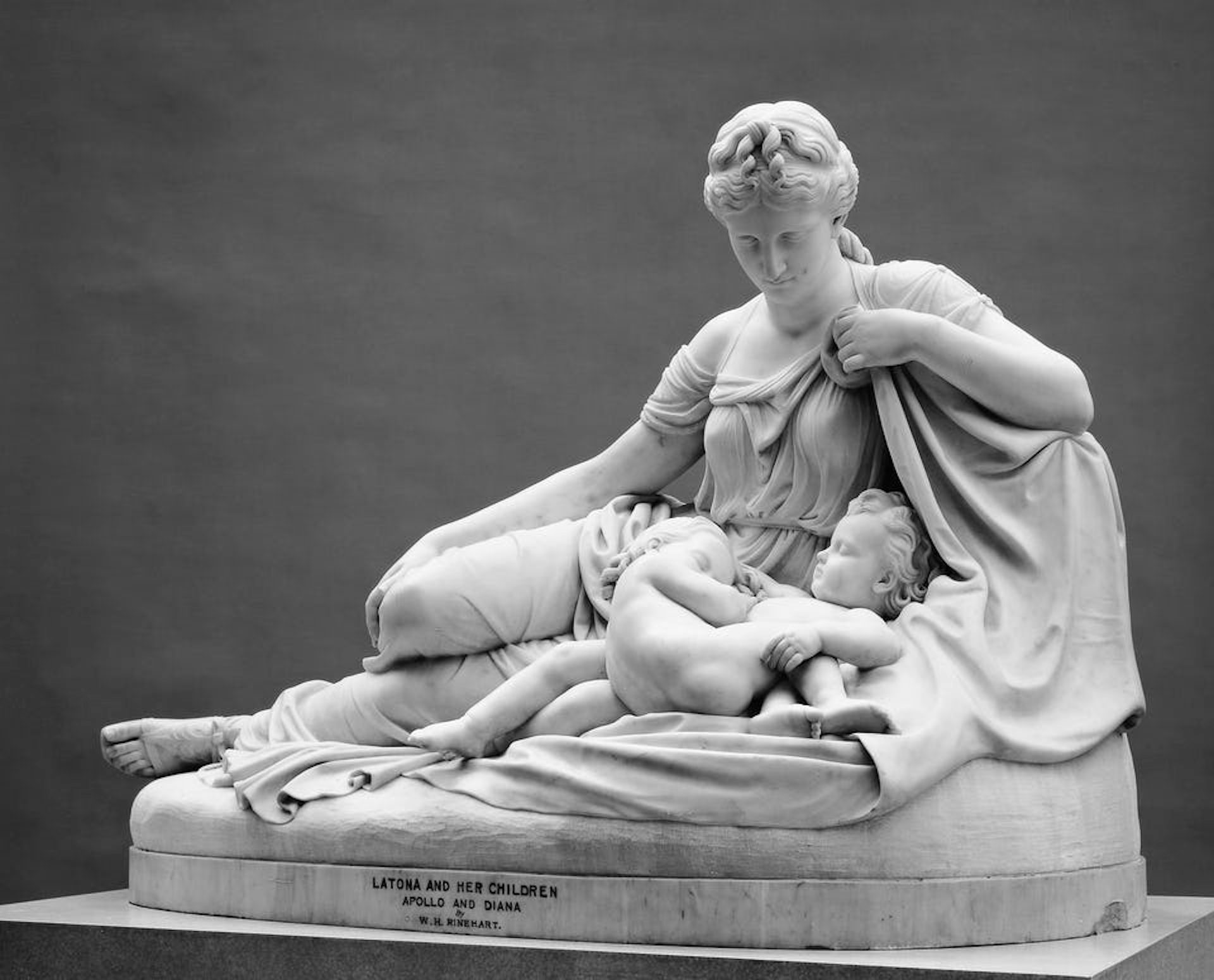

Latona and Her Children by William Henry Rinehart (1874).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAfter a long and painful labor (which Hera extended by preventing her daughter Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, from attending Leto), Apollo and Artemis were finally born. The young Apollo was then wrapped in resplendent robes and fed nectar and ambrosia by Themis, the goddess of law and order. Apollo grew quickly; according to the third Homeric Hymn, he was no sooner born and fed than he announced for all to hear: “The lyre and the curved bow shall ever be dear to me, and I will declare to men the unfailing will of Zeus.”[17]

According to many sources, Delos was a wandering island before Apollo and Artemis were born on it; like Leto, it roamed the world without a place to call its own. But after the twin gods were born, Delos became rooted to its spot. It would forever remain fixed in place as Apollo’s sacred island.[18]

Apollo the Monster-Slayer

Seeking to make a name for himself, the young Apollo decided to hunt the beast known as Python. A son of the primordial earth goddess Gaia, Python was a giant, terrifying dragon. According to the most common tradition, Apollo tracked the beast to Delphi and killed it with his bow and arrows. He then took over the oracle of Delphi and used it as a center from which to dispense his prophecies.

According to the Roman mythographer Hyginus, however, Apollo’s killing of Python was an act of revenge because Python had pursued his mother, Leto, while she was looking for a place to give birth.[19]

Apollo Victorious over the Python by Pietro Francavilla (1591).

Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainIn another story, Apollo, this time together with his sister Artemis, killed the monster Tityus when he attempted to rape their mother, Leto. In some versions of this story, however, Tityus was killed by Zeus,[20] while in others it was Leto herself who killed him.[21]

Apollo, the Killer Musician

Apollo was introduced to music shortly after his birth and soon became known as the greatest musician in the cosmos, a title he took seriously. In one story, told in detail in the Homeric Hymns, Hermes stole a number of cows that belonged to Apollo and hid them inside a cave. While there, Hermes killed a tortoise and fashioned the first lyre from its entrails and shell. Meanwhile, Apollo fumed about the theft and reported it to Zeus, who ordered Hermes to return the stolen cattle. As Hermes was preparing to do so, Apollo noticed him playing the instrument. The young god was so attracted to the object that he agreed to accept it in lieu of the cattle.[22]

Occasionally, the unwise and hubristic would challenge Apollo to musical contests. One challenge occurred when Pan compared his own music to Apollo’s, sparking the god’s outrage. They selected Tmolus, the king of Lydia, to judge a contest. Pan blew a pleasant tune on the pipes, but Apollo played his lyre with such astonishing beauty that he was immediately selected as the victor. When King Midas voiced his disapproval with the outcome, Apollo cursed him with donkey ears.[23]

Cupid and Apollo with a Lyre by Paolo Farinati (ca. 1568).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe punishment for challenging Apollo could also be much more severe. This was the case for the satyr Marsyas, who one day found the aulos, a kind of flute that had been made and discarded by Athena. He learned the instrument well and eventually came to believe himself a better player than Apollo.

Once again, Apollo readied to duel a challenger. Marsyas played well, but the combination of Apollo’s lyre and voice won the day. In some versions of the story, Apollo managed to conclusively prove his superiority by turning his lyre upside down and playing it no less beautifully than before; when Marsyas tried to play the pipes upside down, he was met with less success.[24] In all versions, however, the punishment for his hubris was death. Apollo hung Marsyas from a tree and flayed the skin from his body.

Niobe

Niobe, the wife of King Amphion of Thebes, offers another famous cautionary tale about the consequences of hubris. As the story goes, she had fourteen children: seven boys and seven girls (though the numbers vary in some traditions).[25] One day, Niobe loudly boasted that she was more blessed than even the divine Leto, for she had fourteen beautiful children, while Leto had only two.

To punish Niobe, Leto sent Apollo and Artemis to kill Niobe’s children. Apollo shot down the sons with his bow, while Artemis shot down the daughters with hers. Niobe’s husband Amphion was killed too (though the details of how and why vary). Only Niobe was left. Devastated, she wasted away from grief; her tears became a river, and she herself became a stone. Ovid, the Roman poet who wrote the Metamorphoses, vividly describes the heartrending scene:

Childless—she crouched beside her slaughtered sons, her lifeless daughters, and her husband's corpse. The breeze not even moved her fallen hair, a chill of marble spread upon her flesh, beneath her pale, set brows, her eyes moved not, her bitter tongue turned stiff in her hard jaws, her lovely veins congealed, and her stiff neck and rigid hands could neither bend nor move.—her limbs and body, all were changed to stone.[26]

In some versions, however, at least one of Niobe’s children was spared. Apollodorus calls the survivor Meliboea and claims that Amphion also evaded death.[27] In other sources, however, two children survived, a boy and a girl called Amyclas and Chloris.[28] The Roman mythographer Hyginus even writes that Apollo granted Chloris’ son Nestor the years he had taken away from the Niobids. This was the reason for Nestor’s famous longevity.[29]

Admetus

In another story, Apollo’s son Asclepius had discovered and implemented a cure for death, but Zeus killed him for overstepping the bounds of medicine. When Apollo heard the news, he flew into a rage, slaughtering the Cyclopes who had fashioned the lightning bolt that Zeus used to kill Asclepius. To punish Apollo, Zeus sentenced him to a period of hard labor in service to a mortal man, King Admetus of Pherae.

Apollo submitted to his punishment, caring for Admetus’ herds. But Admetus was a kind man and treated Apollo with respect. In return, Apollo ensured that Admetus prospered. In some traditions, Apollo and Admetus were also lovers.[30]

After his period of service was over, Apollo continued to be a devoted friend and patron of Admetus. When he discovered that Admetus’ life was fated to end soon, he managed to reach a compromise with the Moirae, the three sisters who measured out the life of every mortal: if Admetus could find someone to willingly die for him, he could live.

Apollo took this deal to Admetus, and Admetus’ wife, the lovely Alcestis, chose to die in his place. In the end, however, tragedy was averted and the couple reunited thanks to the brawn of Heracles, another of Admetus’ friends. Heracles happened to stop at Pherae during his travels, and upon learning the circumstances under which Alcestis had died, he conquered death itself to bring her back to her husband.

The Walls of Troy

In one myth, Apollo (together with Poseidon) helped Laomedon, king of Troy, erect the fortifications of his great city.[31] According to some traditions, this task was ordered by Zeus as a punishment for Apollo and Poseidon’s attempt to overthrow him as ruler of the Olympians.[32] In other traditions, however, the two gods went willingly, wishing to test the hubris of Laomedon.[#33]

Apollo and Poseidon performed the work as instructed, though ancient sources disagree on the division of labor. According to some, it was Poseidon who built the fortifications, while Apollo tended Laomedon’s livestock.[34] Pindar even suggests that the two gods were assisted by a mortal named Aeacus. Because Troy was destined to eventually fall, it could not be built by gods alone (such a city would be truly impregnable); consequently, the segment of the wall built by the mortal Aeacus would always be the weak point.[35]

At any rate, Laomedon refused to pay Apollo and Poseidon after they finished building his walls, and even tried to sell them into slavery. This particularly irked the temperamental Poseidon, who sent a sea monster to lay waste to the Trojan countryside. Ultimately, Troy would fall two times: once when Laomedon offended Heracles (in a manner very similar to how he had offended Apollo and Poseidon), and again after the decade-long Trojan War (fought for the love of the beautiful Helen).

Apollo and the Trojan War

During the Trojan War, Apollo vigorously defended the city of Troy. In some traditions, he even had an affair with Hecuba, the queen of Troy. He was also closely associated with the Trojan princess Cassandra, whom he had loved and to whom he had given the art of prophecy.

Throughout the conflict, Apollo was a key mover of events. In the early stages of the war, Apollo’s rage threatened to undo the Achaeans by causing a rift between the mighty heroes Agamemnon and Achilles. This rift began when Agamemnon carried off Chryseis, the daughter of Apollo’s priest Chryses, as a war captive. Chryses first tried to ransom his daughter. Failing this, he prayed for Apollo’s intercession:

Hear me, god of the silver bow, who stand over Chryse and holy Cilla, and rule mightily over Tenedos, Sminthian god, if ever I roofed over a temple to your pleasing, or if ever I burned to you fat thigh-pieces of bulls and goats, fulfill this prayer for me: let the Danaans pay for my tears by your arrows.[36]

Apollo immediately came down from heaven, bringing plague and death in his wake—a terrible sight to behold:

Down from the peaks of Olympus he strode, angered at heart, bearing on his shoulders his bow and covered quiver. The arrows rattled on the shoulders of the angry god as he moved, and his coming was like the night. Then he sat down apart from the ships and let fly an arrow: terrible was the twang of the silver bow. The mules he assailed first and the swift dogs, but then on the men themselves he let fly his stinging shafts, and struck; and constantly the pyres of the dead burned thick.[37]

After numerous deaths, the Greeks realized why they were suffering, and Achilles demanded that Agamemnon return Chryseis to the offended priest. Agamemnon relented, but the goodwill between the two would remain forever broken: Agamemnon took Achilles’ captive, Briseis, to replace Chryseis, and in response, Achilles refused to fight any more for the Greeks.

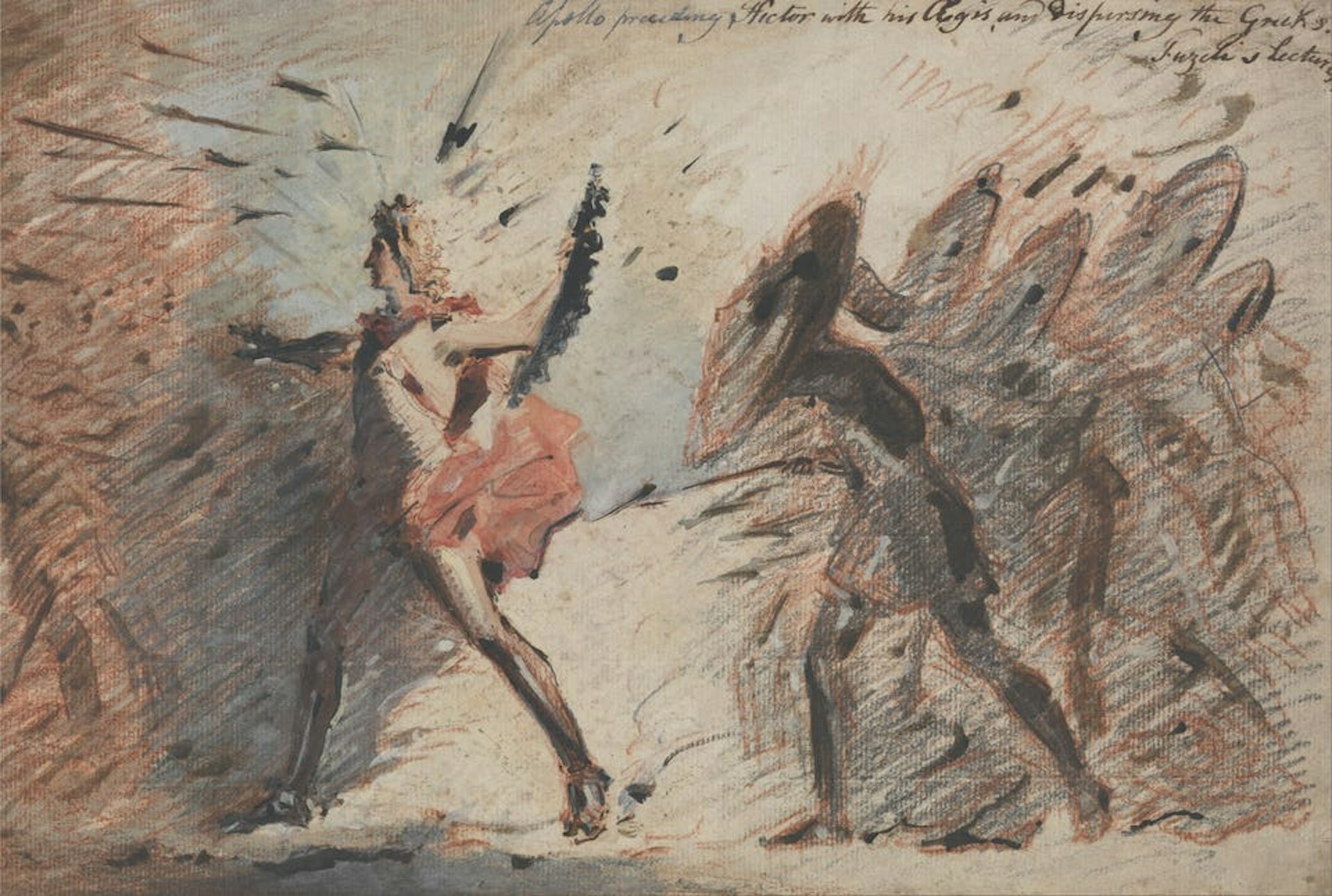

Apollo Preceding Hector with His Aegis and Dispersing the Greeks by John Flaxman (ca. 1787).

Yale Center for British ArtPublic DomainAt other points in the conflict, Apollo fought on the side of the Trojans or interceded on behalf of Trojan heroes such as Aeneas and Hector. When the former fell injured on the battlefield at the hands of Diomedes, Apollo enveloped the scene with a fog that protected Aeneas.[38]

Apollo also helped Hector kill Achilles’ dearest friend, Patroclus, when Patroclus entered the battle in Achilles’ invincible armor.[39] Later, Apollo would use his power again with Hector, who had been bested by Achilles in hand-to-hand combat. When Achilles finally vanquished Hector, Apollo used his protective mist to cover the body, which Achilles had wanted to mutilate in his triumph and rage.[40]

In the end, Apollo brought about the death of the nearly invincible Achilles. Apollo had long nursed a grudge against Achilles for slaying his son Tenes before the Trojan War began. In most traditions, Apollo guided an arrow shot by the Trojan prince Paris to kill Achilles.[41]

Unhappy in Love: Four Romances of Apollo

Apollo, like most of the Greek gods, had many love affairs. Not all of these ended happily, and indeed, many of Apollo’s most famous affairs are tales of disappointment, betrayal, or unrequited love.

In one myth, Apollo fell in love with a beautiful woman named Coronis (though in some traditions, her name was Arsinoe). But Coronis loved the mortal Ischys and slept with him while she was pregnant with Apollo’s child. When Apollo found out about Coronis’ infidelity, he killed her in a jealous rage.

While Coronis’ body was being burned on the funeral pyre, Apollo remembered that the girl was pregnant with his child and removed the baby from the burning body (the first caesarean section). The boy, named Asclepius, became a great physician, though he ended up also dying a tragic death.

Another famous myth is that of Apollo’s homesexual relationship with the handsome youth Hyacinthus. One day, while Apollo and Hyacinthus were training in the fields, Apollo accidentally struck Hyacinthus on the head with a discus, killing the mortal boy. The heartbroken god transformed his deceased lover into a flower, the hyacinth, whose petals formed the Greek word aiai, meaning “alas.”

Other individuals loved by Apollo did not return the god’s love. Daphne, for example, a beautiful nymph, ran from Apollo when he tried to rape her. Just as the god was about to grab her in his arms, Daphne was transformed into a laurel tree. In Ovid’s beautiful rendition,

torpor seized on all her body, and a thin bark closed around her gentle bosom, and her hair became as moving leaves; her arms were changed to waving branches, and her active feet as clinging roots were fastened to the ground—her face was hidden with encircling leaves.[42]

Even in her new form, Daphne would forever hold a special place in Apollo’s heart: Apollo decreed that the laurel wreath would be worn by his priests and priestesses and by the winners of the Pythian Games held at Delphi in his honor.

Apollo also loved the beautiful Cassandra, a Trojan princess who was the daughter of Priam and Hecuba. Apollo gave Cassandra the gift of prophecy, hoping she would sleep with him in return; when Cassandra refused, Apollo cursed her so that nobody would believe her prophecies. Thus, even though Cassandra repeatedly warned her people that the city of Troy would fall, nobody listened.

Other Myths

Apollo is virtually ubiquitous in Greek mythology. The myths outlined above represent only a small fraction of the countless stories in which Apollo played a part.

Other noteworthy myths describe Apollo’s role in the Gigantomachy, the terrible war between the Olympians and the Giants. In most sources, Apollo was one of the gods who battled a Giant named Ephialtes, and according to Pindar, it was he who killed the Giant Porphyrion with his arrows.[43]

Apollo was also usually depicted as the god who killed the Aloadae, Otus and Ephialtes. These two cocky brothers wanted to carry off Hera and Artemis to be their wives. Thus, they piled two mountains on top of each other and attacked the gods on Olympus. In some versions, Apollo killed the Aloadae with his arrows.[44] In other versions, Apollo used a trick to kill them: he sent a deer between the brothers, and when they threw their javelins at the animal, they each struck the other instead.[45]

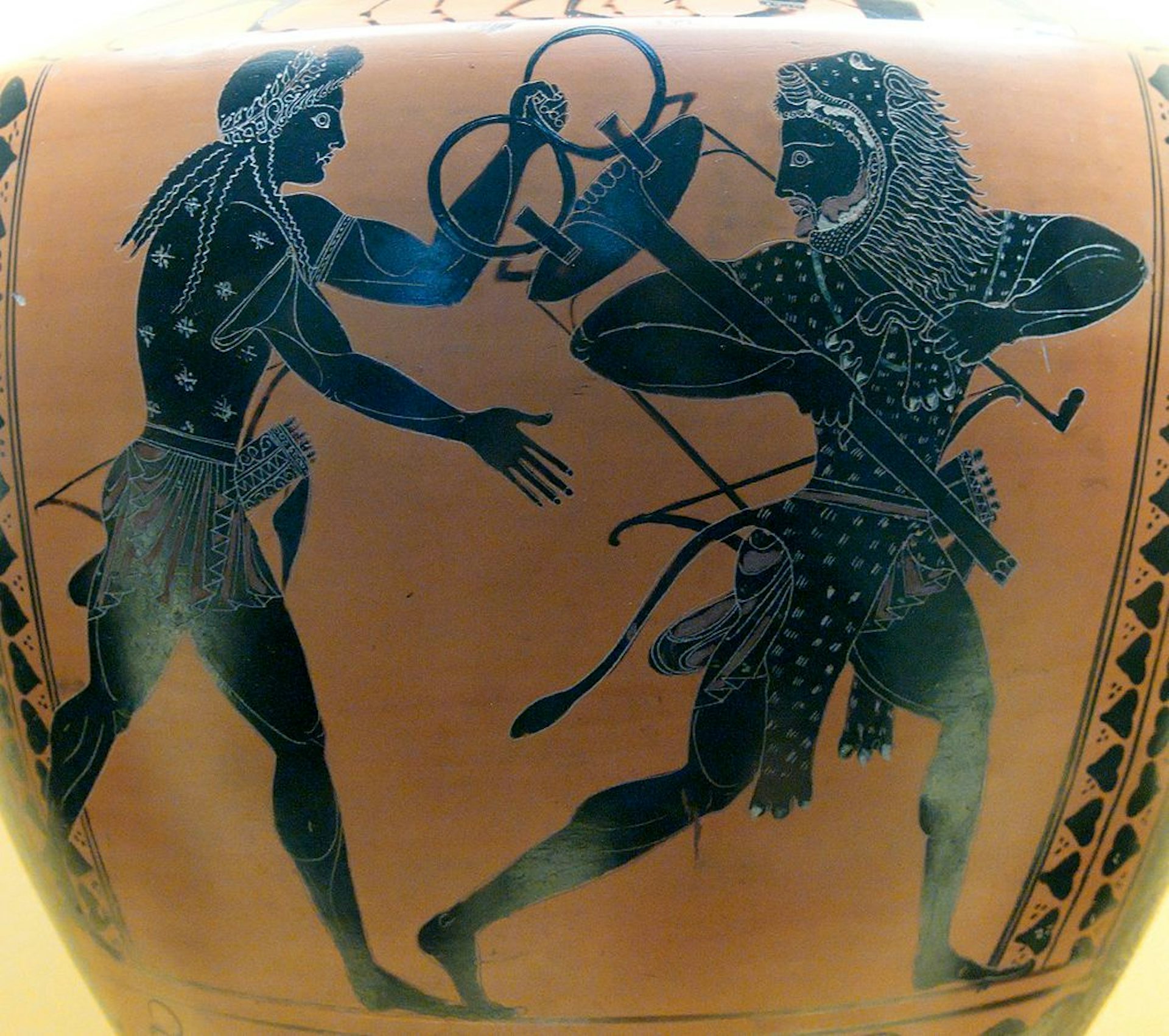

In another popular myth—one that was a common theme in Greek art—Apollo fought with Heracles. As the story goes, Heracles consulted Apollo’s oracle at Delphi on a matter but was unhappy with the response; consequently, he tried to steal the Delphic tripod in order to start his own oracle. Apollo immediately came down from Olympus and tried to wrestle the tripod away from Heracles. The battle only ended when Zeus separated the half-brothers.

Hydria depicting Apollo and Heracles fighting for the Delphic tripod by the Madrid Painter (ca. 520 BCE).

Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia CommonsApollo and the Greeks

Apollo was the ultimate expression of Greek culture as the Greeks envisioned it: youthful and vital, powerful and wise, peaceful (with the occasional outburst of righteous fury), full of light, poetry, music, and civilization. It was this positive cultural representation that made Apollo so widely loved and admired throughout the Greek world. Even his fluid sexuality suggests a culture that embraced the erotic pleasures of both sexes. With so many temples, statues, and other monuments built in Apollo’s honor, admiration for the deity cannot be overstated.

Worship

Festivals

The most important of Apollo’s festivals were the Pythian Games, held every four years at Delphi. Events included both athletic contests (wrestling, running, horse and chariot racing, etc.) and artistic contests (music, poetry, and even painting). Uniquely for the ancient Greek world, women were allowed to compete in most events. Winners were crowned with a wreath of laurel leaves.

According to legend, the Pythian Games were instituted by Apollo himself after he vanquished the monster Python and made Delphi his oracle. Historians, however, generally agree that the Pythian Games began around 582 BCE.

Another important festival of Apollo was the Delia, celebrated on the sacred island of Delos every four years. During the Delia, visitors and pilgrims from all over Greece would gather on Delos for musical performances, sacrifices, and feasting.

There were countless other festivals of Apollo that were celebrated throughout the cities of ancient Greece. In Athens, annual festivals of Apollo included the Boedromia, Metageitnia, Pyanepsia, and Thargelia. In Sparta, annual festivals included the Carneia and Hyacinthia (the latter named for Apollo’s lover Hyacinthus, said to have been a Spartan prince). In Thebes, the Daphnephoria, a great festival in honor of Apollo, was celebrated every nine years.

Temples

Apollo had numerous temples, sanctuaries, and shrines throughout Greece. Temple worship of Apollo is attested from an early date: some of the god’s temples can be traced back as far as the ninth century BCE. Many of these ancient temples, moreover, were actually built over cult sites in use since the Mycenaean Period (ca. 1600–1100 BCE).

In the Greek world, Apollo was first and foremost a god of prophecy and divination. Indeed, almost all of Apollo’s major temples in ancient Greece highlighted his prophetic function, with the exception of the temple on Delos. But Apollo was also widely worshipped as the god of music and the arts, colonization, and healing and medicine.

Perhaps the most important of Apollo’s temples was his temple and oracle at Delphi. Here, a priestess called a pythia delivered Apollo’s prophecies and advice. It was said that the pythia became inspired by breathing vapors arising from a spring that flowed underneath the temple. Scholars have long been divided over the veracity of this claim, and archaeological and geological investigation into possible fumes arising from faultlines beneath Delphi continues to this day.[46]

Ruins of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, Greece (fourth century BCE).

Bernard Gagnon / Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Apollo had other major oracles scattered throughout the Greek world: at Thebes and Mount Ptoos in Boeotia; at Abae in Phocis; and at Didyma, Claros, and Pergamum in Asia Minor. Apollo also had important temples at Gortyn and Dreros in Crete and at Syracuse and Selinus in Sicily.

Apollo was worshipped widely in Italy, especially at Magna Graecia and Etruria. However, he was virtually unheard of in Rome until relatively late, and his first temples there only appear around the fifth century BCE. In the Roman world, Apollo was worshipped primarily in his capacity as a healer. His oracular priestesses in Italy were called sibyls.

Pop Culture

Apollo has been regularly featured in popular culture, though these depictions are often brief and superficial, failing to capture the complexity of his ancient personae. In both Percy Jackson and the Olympians, a book series by Rick Riordan, and the God of War video game series, Apollo plays only a small role.

Apollo has a unique connection to modern culture through space travel. Drawing on his association with the sun (an association that, contrary to popular belief, did not enter Apollo’s theology until relatively late), NASA named their famous moon-bound space program after Apollo. They hoped to emulate the exceptionally accurate archer in their journey to the moon.