Artemis

Tondo of an Attic red-figure cup by the Brygos Painter showing Apollo (left) and his sister Artemis (right) (ca. 470 BCE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainOverview

Artemis was the Greek goddess of the hunt, nature, and wild animals. She was typically regarded as one of the major Olympians, numbered among the so-called “Twelve Gods.”

In art and literature, Artemis was often imagined hunting in the forest with her bow. While her twin brother Apollo represented reason and order, Artemis signified the wilder and more untamed aspects of human and natural life.

Key Facts

Who were Artemis’ parents?

Artemis, like her twin brother Apollo, was born from the union of the supreme god Zeus and the goddess Leto. She was most likely born on the island of Delos (though some sources placed her birth on a different island nearby). Delos later became the site of one of Apollo’s most important sanctuaries.

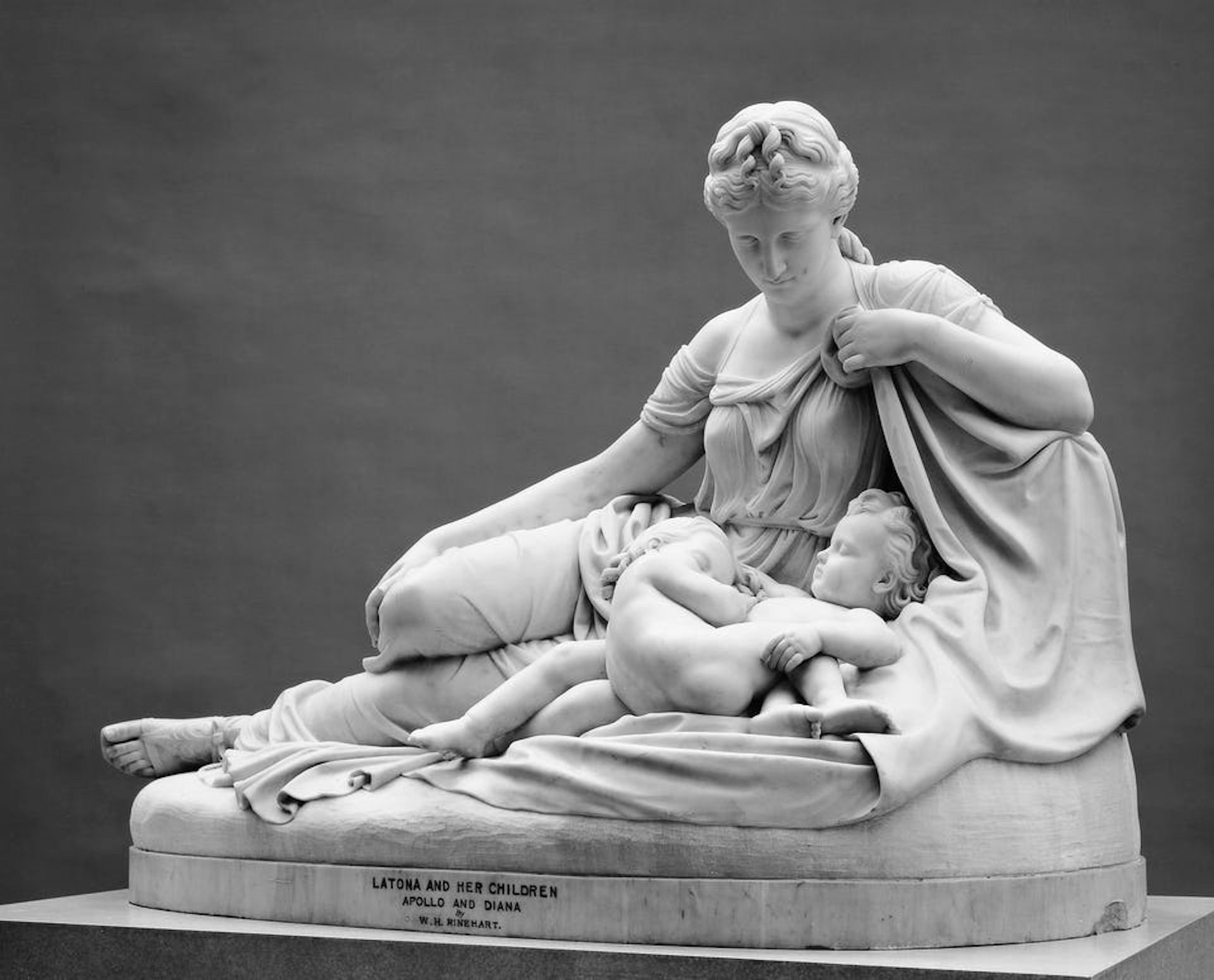

Latona and Her Children by William Henry Rinehart (1874).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhat were Artemis’ attributes?

Artemis’ most recognizable attribute was probably her bow, though she was sometimes shown with other weapons as well. She was generally depicted clad in a short hunter’s tunic. Artemis’ entourage included nymphs and woodland animals such as deer and bears.

Statue of Artemis killing a deer from Delos (ca. 125–100 BCE)

Archaeological Museum, Delos / Olaf TauschCC BY 3.0The Bath of Artemis

Artemis was notoriously protective of her chastity. One well-known myth told of how the Theban prince Actaeon was out hunting in the woods when he stumbled upon Artemis bathing in a stream. Horrified that a mortal man had seen her naked, Artemis transformed the unfortunate Actaeon into a deer. Actaeon’s hunting dogs promptly turned on him and, failing to recognize their master, tore him apart.

Diana and Actaeon by Giuseppe Cesari (1602–1603)

Museum of Fine Arts, BudapestPublic DomainEtymology

Speculation over the etymology of the name “Artemis” began in antiquity. In Cratylus, Plato traced the name’s origins to the Greek word artemēs, meaning “pure” or “unblemished.”[1] Though this is a tempting theory—the words are similar, and the quality of purity nicely captures Artemis’ nature—it is most likely too neat to be true. Most scholars and linguists today regard Plato’s interpretation as a folk etymology.

The search for the origins of Artemis’ name are made even more difficult by the fact that there is no clear consensus on how old it is. Some scholars have suggested that the name “Artemis” appears in the first Greek texts, equating the goddess of the hunt with a-te-mi-to or a-te-mi-te in the Linear B script (the writing system in use ca. 1600–1100 BCE, prior to the development of the Greek alphabet). If this is correct, it would mean that Artemis was known and worshipped in Greece from the earliest times. However, it is still disputed whether Artemis and a-te-mi-to/a-te-mi-te refer to the same entity.[2]

While there is no widely agreed-upon etymology for “Artemis,” several hypotheses have nevertheless gained popularity. According to some, Artemis’ name is related to the Greek word arktos, meaning “bear” (from the Proto-Indo-European *h₂ŕ̥tḱos). Indeed, Artemis was closely associated with a bear cult in Attica and was often depicted alongside bears (as well as a number of other animals, such as deer, boars, and hunting dogs).[3]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Artemis Ἄρτεμις Phonetic

IPA

[AHR-tuh-mis] /ˈɑr tə mɪs/

Other Names

The Roman counterpart of Artemis was called Diana. Artemis was sometimes also referred to as Phoebe by both the Greeks and Romans, though this did not become a common alternative name or epithet until a relatively late historical period.

Artemis was sometimes identified with other deities, especially Hecate (a goddess of boundaries and witchcraft) and Eileithyia (the goddess of childbirth). “Hecate” and “Eileithyia” were also among the epithets of Artemis. Later on—that is, during the Hellenistic period (323 BCE–31 BCE) and Imperial period (after 31 BCE), Artemis was increasingly identified with the moon and the moon goddess Selene.

Epithets

Among Artemis’ most important epithets were agrotera (“she of the hunt”), keladeinē (“strong-voiced”), and parthenos (“virgin”). Like her brother Apollo, Artemis also boasted many epithets relating to archery. These included hekatēbolos and hekatē (“far-shooter”), hekaergē (“far-worker”), and iocheaira (“she of the showering arrows”). Artemis also had many epithets related to her ritual functions or places of worship, such as Delia (“Delian,” referring to the island where she and Apollo were born), sōteira (“savior”), phōsphoros (“bringer of light”), and eileithyia (in her capacity as a goddess of childbirth).

Attributes

Domains

Artemis’ primary domains were hunting and all aspects of initiation (especially female initiation).

Artemis offered something for nearly everyone. Among hunters and rustics, she was the source of cyclic growth. It was she who controlled the rhythms of nature and the whims of the creatures in it. For maidens and the young, she was a beacon of innocence and chastity. For mothers, she was a symbol of fecundity and health, as well as a midwife to their babies (just like Eileithyia, with whom she was sometimes conflated).

Artemis also presided over initiation rites and the passage of females (but also males) from one life stage to another (childhood to adulthood, virginity to marriage, marriage to parenthood, etc.).

Iconography and Symbols

Artemis herself was a virgin goddess, in many ways more mannish than effeminate. She was known to roam the mountains and forests in search of game. In art, Artemis was often shown wearing a short hunter’s tunic and carrying a bow or spear. Her entourage was made up of nymphs and wild animals.

Artemis’ symbols included her weapons and hunting gear (the bow and arrow or the spear); her sacred animals, such as deer, boar, and bears; and her sacred plants, such as the cypress and palm. In later art and literature, Artemis came to be associated with the moon (complementing her brother Apollo, associated with the sun).

The common representation of Artemis is as a young, beautiful virgin, clad for the hunt. There is one important local variation, however. At Ephesus (a Greek city on the coast of modern Turkey), Artemis was identified with a fertility goddess called either the “Lady of Ephesus” or the “Artemis of Ephesus.” The cult statues of this Artemis were very different from those of the more familiar Artemis, showing the goddess decked out in elaborate jewelry, headdress, and—most striking of all—with small ovals covering her upper body. These ovals seem to have symbolized fertility; they have been variously interpreted as breasts, eggs, or scrotal sacs.

Statue of the "Artemis of Ephesus" type (second century CE). The head, hands, and feet are a modern restoration by Giuseppe Valadier.

Marie-Lan Nguyen / Naples National Archaeological MuseumFamily

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

The birth of Artemis and Apollo was full of the drama that so characterized Greek mythology. Artemis’ mother, Leto—herself the daughter of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe—was one of Zeus’ many lovers. When she became pregnant by Zeus, he was already married to his sister Hera, who was notoriously prone to jealousy.

True to form, Leto’s condition aroused Hera’s fury, and Hera threatened any person or land that harbored Leto. According to some traditions, Hera even sent her son Ares to pursue Leto as she wandered through the world looking for a place to give birth.[7] In other traditions, it was the monster Python whom Hera sent to pursue Leto.[8]

Abandoned by the gods, Leto continued wandering until she found shelter on a tiny and forgotten island called Delos. There Leto readied to have her twins, but Hera was not yet done with her. When Leto went into labor, Hera prevented Eileithyia, her daughter and the goddess of midwifery, from attending to Leto. After a long and painful labor (which lasted as many as nine days, according to some sources), Leto managed to give birth to the brilliant twins Artemis and Apollo.

Bell krater showing Artemis and Apollo offering libations with their mother Leto, attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter (ca. 450 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn some traditions, Artemis was the first of the twins to be born and actually helped her mother give birth to Apollo.[9] This would have represented Artemis’ very first foray into her function as a goddess of childbirth.

Though most ancient sources agreed that Apollo and Artemis were both born on Delos, there were other versions circulating in antiquity. Some claimed that Artemis’ true birthplace was the grove of Ortygia, near Ephesus, a region in Asia Minor;[10] others said it was Crete.[11]

Childhood

The third-century BCE poet Callimachus gives an idyllic account of Artemis’ childhood in his third Hymn. According to this poem, the young Artemis sat on the knees of her mighty father, Zeus, and boldly demanded that he grant all her requests, including that she be allowed to remain a virgin and a huntress:

Give me to keep my maidenhood, Father, forever: and give me to be of many names, that Phoebus may not vie with me. And give me arrows and a bow – stay, Father, I ask thee not for quiver or for mighty bow: for me the Cyclopes will straightway fashion arrows and fashion for me a well-bent bow. But give me to be Bringer of Light and give me to gird me in a tunic with embroidered border reaching to the knee, that I may slay wild beasts. And give me sixty daughters of Oceanus for my choir – all nine years old, all maidens yet ungirdled; and give me for handmaidens twenty nymphs of Amnisus who shall tend well my buskins, and, when I shoot no more at lynx or stag, shall tend my swift hounds. And give to me all mountains; and for city, assign me any, even whatsoever thou wilt: for seldom is it that Artemis goes down to the town. On the mountains will I dwell and the cities of men I will visit only when women vexed by the sharp pang of childbirth call me to their aid even in the hour when I was born the Fates ordained that I should be their helper, forasmuch as my mother suffered no pain either when she gave me birth or when she carried me in her womb, but without travail put me from her body.[12]

Zeus, of course, agreed immediately to the requests of his darling daughter.

Callimachus’ poem also relates how Artemis acquired her silver bow and arrows from the smith god Hephaestus and his workers, the Cyclopes; how Pan awarded her thirteen hounds (seven female, six male) to accompany her on the hunt; how she captured six golden-antlered deer to pull her chariot; and how she became an expert archer, progressing from shooting at stationary targets to wild game.[13]

This, then, was how Artemis spent her productive childhood and youth. When she ascended to Olympus to take her place among the Twelve Olympians, she sat on a throne beside her twin brother, Apollo.

The Wrath of Artemis

Though known for her innocence and purity, Artemis had a great capacity for violence and cruelty. She fiercely defended her virginity and her reputation as the greatest of hunters. In fact, the bulk of Artemis’ mythos relates to her colorful punishments of those who offended her or her family.

The following are several famous myths that put Artemis’ destructive potential on full display.

Orion

Orion was a great hunter who often prowled the woods with Artemis and who, according to most variants, fell in love with the dashing huntress. In some versions, Orion attempted to rape Artemis, who fended off his attempts and killed him (either with her arrows or by sending a giant scorpion against him).[14]

In other versions of the story, it was not Artemis but one of Artemis’ attendants that Orion attempted to rape, and this was the offense that caused Artemis to kill him.[15] In others, Artemis killed Orion after he had the hubris to challenge her to a discus competition.[16] In others still, Orion fell in love with Eos, the goddess of dawn, and Artemis killed him out of jealousy.[17]

Diana Mourning the Death of Orion by Etienne Delaune (1547–1548).

RijksmuseumPublic DomainA more nuanced variant had Apollo inciting the clash between Artemis and Orion. In this version, Apollo was worried that Artemis’ budding love for Orion would overcome her will to preserve her chastity. One day, when Orion went swimming in a large lake and had swum so far away that his head was a mere speck on the horizon, Apollo challenged Artemis. Questioning her skill with the bow, he claimed that she could probably not even hit the distant speck in the lake. Taking the bait, Artemis immediately drew the bow and scored a perfect shot, killing her companion in the process. So great was her anguish that Artemis implored Zeus to memorialize him with a constellation in the stars.[18]

To add to the confusion, there were other traditions in which it was not even Artemis who killed Orion. Instead, these traditions claimed that Gaia sent the scorpion to kill Orion, out of fear that he would kill all the animals on earth.[19]

The Aloadae

Otus and Ephialtes, known as the Aloadae, learned of Artemis’ wrath the hard way. The Aloadae were brutal giants and hunters who never stopped growing. Boasting that they would soon grow large enough to reach the top of Olympus, they promised to abduct Hera and Artemis and take them as their wives.

There are different versions of the fate of the Aloadae. In some traditions, Apollo killed them with his arrows.[20] But in other traditions, they were killed by a trick. Clever hunter that she was, Artemis turned herself into a beautiful doe and jumped out between the brothers, causing them to eagerly throw their spears at her. Artemis deftly avoided the spears, however, and they went hurtling into each of the brothers instead, killing them.[21]

Niobe

Perhaps the cruelest fate of all was reserved for Niobe, the queen of Thebes and wife of Amphion. Niobe was a fruitful mother who had seven boys and seven girls.[22] In her pride, Niobe proclaimed that she was more fertile than Leto, who had only one boy and one girl.

Artemis and Apollo loved their mother very much, and their wrath was severe (and arguably disproportionate). Using their unerring arrows, Artemis killed Niobe’s seven daughters while Apollo claimed her sons. In some versions, the twin deities spared one of each sex.[23] Niobe, overwhelmed by grief, cried herself a river (literally) and was turned to stone.

Actaeon

Actaeon was a great hunter and a prince of Thebes. One day, he happened to see Artemis nude as she was bathing in a river. Horrified that a mortal had transgressed her modesty (even unintentionally), Artemis turned the young man into a stag. Actaeon’s own dogs, no longer recognizing their master, then pounced on him in stag form and devoured him.

In other, less-familiar variants, Actaeon actually deliberately spied on Artemis while she was bathing,[24] while in others he attempted to rape Artemis or simply boasted that he was a better hunter than she was.[25]

Diana and Actaeon (from a set of Ovid's Metamorphoses), designed before 1680, woven late 17th–early 18th century. Woven at or near Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainCallisto

Actaeon was not the only person destroyed by Artemis for an offense that was not (in most traditions at least) his fault. Among Artemis’ attendants was the nymph Callisto, whose beauty earned her the unwanted attention of Zeus. After Zeus had slept with Callisto and impregnated her, the girl was not long for this world.

In some stories, Artemis noticed that Callisto was pregnant. This enraged her, as all her attendants were sworn to remain virgins forever; she punished Callisto by turning her into a bear. In other versions, Callisto had been turned into a bear by somebody else (either Hera or Zeus) and was shot and killed by Artemis.[26]

In yet another version, recounted in two poems by Ovid, Artemis merely banished the pregnant Callisto from her entourage, angry that the girl had broken her oath to remain a virgin. Hera then transformed her into a bear. In this form, Callisto was finally killed one day by her own son Arcas, who was out hunting and did not recognize her.[27]

Agamemnon

Agamemnon was a powerful king of Mycenae who led the Greek army during the Trojan War. While the Greeks were preparing to sail to Troy, Agamemnon offended Artemis somehow (sources diverge regarding the exact details); as punishment, Artemis ordered him to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia to her. If Agamemnon did not sacrifice the girl, the winds would never blow him and his army to Troy.

Agamemnon finally gave in and ordered Iphigenia to be killed. In some versions of the myth, however, Artemis took pity on the innocent girl and rescued her at the last minute; she replaced her with an animal that the Greeks sacrificed in her place.[28]

Other Myths: Giants, Monsters, and Mortals

There were many others who suffered from Artemis’ wrath. During the Gigantomachy—in which the Giants, monstrous offspring of Gaia, attacked Olympus—Artemis took part in the fighting and was sometimes said to have killed the Giant Gration.[29] When the monster Tityus attacked Leto, most variants agreed that Artemis was involved in killing him.[30] In some traditions, Artemis also helped Apollo kill the monster Python, whose death enabled Apollo to take over the oracle of Delphi.[31]

Artemis was also involved in the death of Adonis, a mortal lover of Aphrodite. Aphrodite had been responsible for the death of Hippolytus, a virginal young man whom Artemis loved dearly. In revenge, Artemis plotted the death of Aphrodite’s darling Adonis (in most versions, by sending a wild boar to gore him).

On another occasion, Artemis was offended by Oeneus, the king of Calydon. She punished the king by sending a monstrous boar to ravage his countryside—the so-called “Calydonian Boar.” Oeneus and his son Meleager summoned all the greatest heroes of Greece to hunt down the creature, thus sparking the myth of the Calydonian Boar Hunt.

Artemis also fended off numerous other men who threatened her chastity, including the river god Alpheus, the second-generation Titan Buphagus, and the young Sipriotes.

Artemis in Homer

Like her brother Apollo, Homer’s Artemis was an ally of the Trojans and an enemy of the Greeks during the Trojan War. Mythology tells of how Artemis was initially drawn into the conflict by King Agamemnon, whose daughter Iphigenia she demanded as a sacrifice. However, this story does not appear in Homer’s epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

During the war, Artemis did not play as important a role as some of the other gods, such as Zeus, Athena, or Apollo. However, she did help heal the Trojan hero Aeneas after he was injured in battle.[32] According to the Iliad, tensions on Olympus eventually broke out into full-fledged brawling, and the pro-Greek Hera memorably beat up the pro-Trojan Artemis. The bruised Artemis ran away crying to her father, Zeus.[33]

Worship

Festivals

Artemis was honored in numerous festivals and celebrations. In Attica, important festivals included the Elaphebolia, which involved making stag-shaped cakes in honor of Artemis; the Charisteria, which celebrated the famous Greek victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE; the Munichia, which included a goat sacrifice; and the Brauronia, in which young girls between the ages of five and ten dressed up and danced like bears (in atonement for the mythical killing of one of Artemis’ sacred bears in Attica).

In Sparta, Artemis was worshipped as Artemis Orthia and was associated with sinister rituals. The Roman statesman and writer Cicero describes how, at the festival of Artemis Orthia, a young man was whipped at the goddess’s altar until he bled.[34] Another infamous festival of Artemis Orthia involved a competition between two groups of young Spartan boys in which each group tried to steal cheese that had been placed on the altar. As the boys attempted the theft, they were beaten mercilessly. Whichever team managed to endure the beatings best and steal more cheese was declared the winner.[35] Such rituals were sometimes interpreted as replacements for human sacrifices that used to be offered to Artemis Orthia.[36]

Another important festival of Artemis was called the Laphria. It was held at Patrae, in southern Greece. The ceremony involved a huge procession that ended with throwing animal sacrifices into a bonfire.

Artemis’ birthday (generally assigned to the sixth day of the Greek month Thargelion, around late May) was also celebrated in many places.

Temples

Artemis’ most important temples were located on the island of Delos, at Brauron and Munichia (in the region of Attica), at Sparta, and at Ephesus (in Asia Minor).

The last of these—the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus—was known to have been especially grand. Built in the middle of the sixth century BCE, this temple stood for centuries; yet today, little more than a single column remains. The ancients, from Herodotus to Plutarch, marveled at its beauty and size (roughly double the size of the Parthenon in Athens). Antipater of Sidon, a Hellenistic poet of the late second century BCE, ranked it as the most magnificent of ancient sites:

I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, “Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand.”[37]

The temple was razed by an arsonist in the fourth century BCE, then rebuilt on new foundations, only to be ransacked by the Goths in the third century CE. It was finally destroyed as a pagan idol at the behest of the Christian emperor Theodosius in 401 CE.

Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (mid-6th century BCE).

Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 4.0Pop Culture

Artemis regularly appears in modern adaptations of Greek mythology, such as the Percy Jackson and the Olympians book series by Rick Riordan and the God of War video game series. She is also featured in the 1990s TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys.

Artemis is often remembered first and foremost as an archer and is therefore invoked as a symbol of swiftness and accuracy; for example, Artemis Racing is a professional sailing team that has competed in America’s Cup.

The Artemis archetype—a young girl, often withdrawn from life, who bravely transgresses physical and moral boundaries and fights fiercely for what is right—has become especially popular in the last decade. This archetype is perhaps best exemplified by the character of Katniss Everdeen, the heroine of Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games novels. Like her inspiration, Katniss even wields a bow in her quest for justice.

Artemis has also lent her name to the Artemisia, a genus of plants used in a variety of herbal and medicinal preparations. The genus was so named because analgesics made from the plants were used by midwives, and Artemis was a goddess of midwifery. Besides the analgesics, Artemisia plants make up the wormwood used in absinthe as well as Artemisinin, a compound used in the treatment for malaria.