Achilles

The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis by Joachim Wtewael (1612)

Clark Art Institute, WilliamstownPublic DomainOverview

Achilles, son of Peleus and Thetis, was one of the greatest heroes and warriors of Greek mythology. He was raised by the centaur Chiron and fought in the Trojan War, where he gained fame and glory. But this glory came at a cost, for Achilles was destined to die young.

Achilles was instrumental in keeping the Trojans at bay during the decade-long Trojan War. During the final year of the war, he accomplished his most notable deed: he killed Hector, the commander of the Trojan army, to avenge the death of his friend Patroclus. But Achilles himself was to die soon after, shot down at the gates of Troy by Paris and Apollo.

Who were Achilles’ parents?

Achilles’ father was Peleus, a great hero who had sailed with the Argonauts and who eventually became the king of Phthia in northern Greece. His mother was Thetis, one of the fifty sea goddesses known as the Nereids.

The marriage of Peleus and Thetis was not a particularly happy one. According to most accounts, Thetis soon tired of her mortal husband and left him to go live with her father and sisters in the depths of the sea. But she still cared for her son Achilles and made sure he was brought up and trained well.

The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis by Jacob Jordaens after Peter Paul Rubens (between 1633 and 1638)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainWho mentored Achilles?

Achilles was raised by Chiron, the wisest of the centaurs. Chiron, who had also taught heroes such as Jason and Heracles, lived on Mount Parnassus in northern Greece. He not only taught Achilles how to fight but also trained him in medicine and music.

Just before the Trojan War broke out, Achilles’ mother took him away from Chiron and hid him on the island of Scyros, hoping to prevent him from taking part in the dangerous conflict. She disguised Achilles as a girl and left him in the court of the Scyrian king Lycomedes. But Achilles was eventually discovered by the cunning Odysseus and accompanied the Greeks to Troy after all.

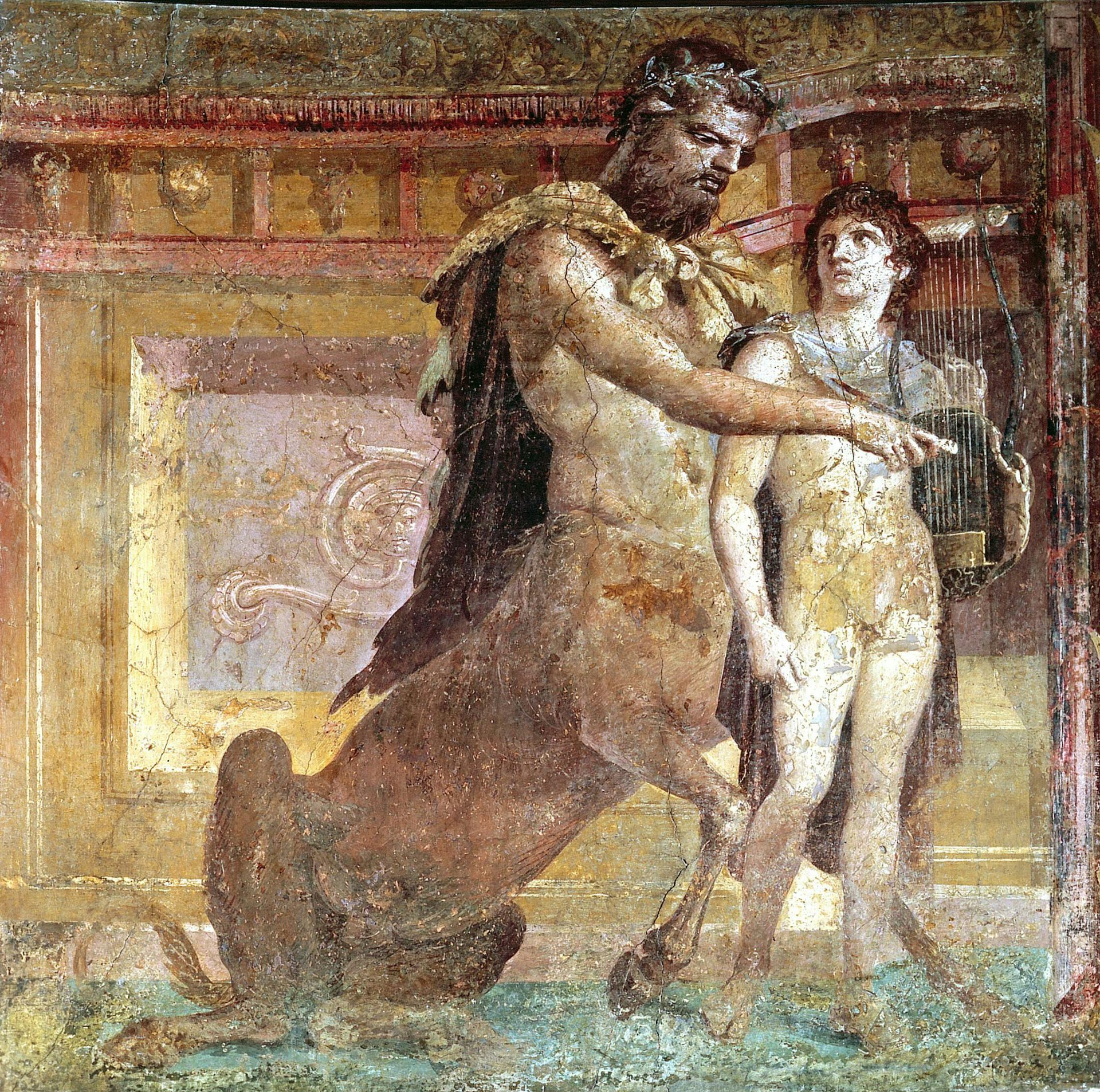

Fresco showing Chiron (left) with the young Achilles (right) from Herculaneum (1st century BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, NaplesPublic DomainHow did Achilles die?

Achilles was killed during the final year of the Trojan War, while he was still very young. There are different accounts of how he died, but in virtually all of them, he was killed by the Trojan prince Paris with the help of the god Apollo.

In what became the most familiar tradition, Paris pierced Achilles in the heel with an arrow guided by Apollo. Some said that Achilles was invulnerable everywhere except his heel and thus perished from his wound (though the earliest sources fail to mention Achilles’ heel).

The Death of Achilles by Peter Paul Rubens (ca. 1635)

Courtauld Gallery, LondonPublic DomainAchilles in the Trojan War

Achilles was a great warrior who was instrumental to the capture of Troy. One prophecy even said that Troy could not be taken without Achilles’ help. Though he knew he was destined to die young if he took part in the war, Achilles nonetheless agreed to accompany the Greeks to Troy, choosing glory in battle over a long life.

Despite his formidable military prowess, Achilles was very proud, and he almost cost the Greeks the war when he quarreled with the Greek commander Agamemnon. Their dispute led to the deaths of many Greek warriors, including Achilles’ close friend Patroclus.

To avenge Patroclus’ death, Achilles killed the Trojan champion Hector, making a Greek victory all but inevitable. But by choosing to win fame at Troy, Achilles also doomed himself to an early death. He was killed soon after slaying Hector, shot down by the arrows of the Trojan prince Paris (Hector’s brother).

The Wrath of Achilles by François-Léon Benouville (1847)

Musée Fabre, MontpellierPublic DomainEtymology

The name Achilles (“Achilleus” is the Greek pronunciation) is an old one, found on tablets from the Mycenaean Period (ca. 1700–1100 BCE). Originally written in a script called Linear B, which predates the Greek alphabet, the name appears on these tablets in the forms a-ki-re-u[1] and a-ki-re-we.[2]

Etymological explanations for the name are diverse and uncertain: ancient sources sometimes derived the name from the words achos (“sorrow”) and laos (“people”), as the myths of Achilles stress the sorrow he caused to the Trojans.[3]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Achilles Ἀχιλλεύς Phonetic

IPA

[uh-KI-leez] /əˈkɪliːz/

Titles and Epithets

Achilles’ epithets in Greek literature (especially the Homeric epics) include “swift-footed” (podarkēs/podas ōkys) and “brilliant” (dios).

Alternate Names

According to Apollodorus, Achilles was originally named Ligyron. It was changed to Achilles after his mother, Thetis, abandoned him because he had never put his lips to her breast to nurse. In this version, the name Achilles translates to “no lips,” from cheilēs (“lips”) and the prefix a- (which expresses negation).[6]

Attributes

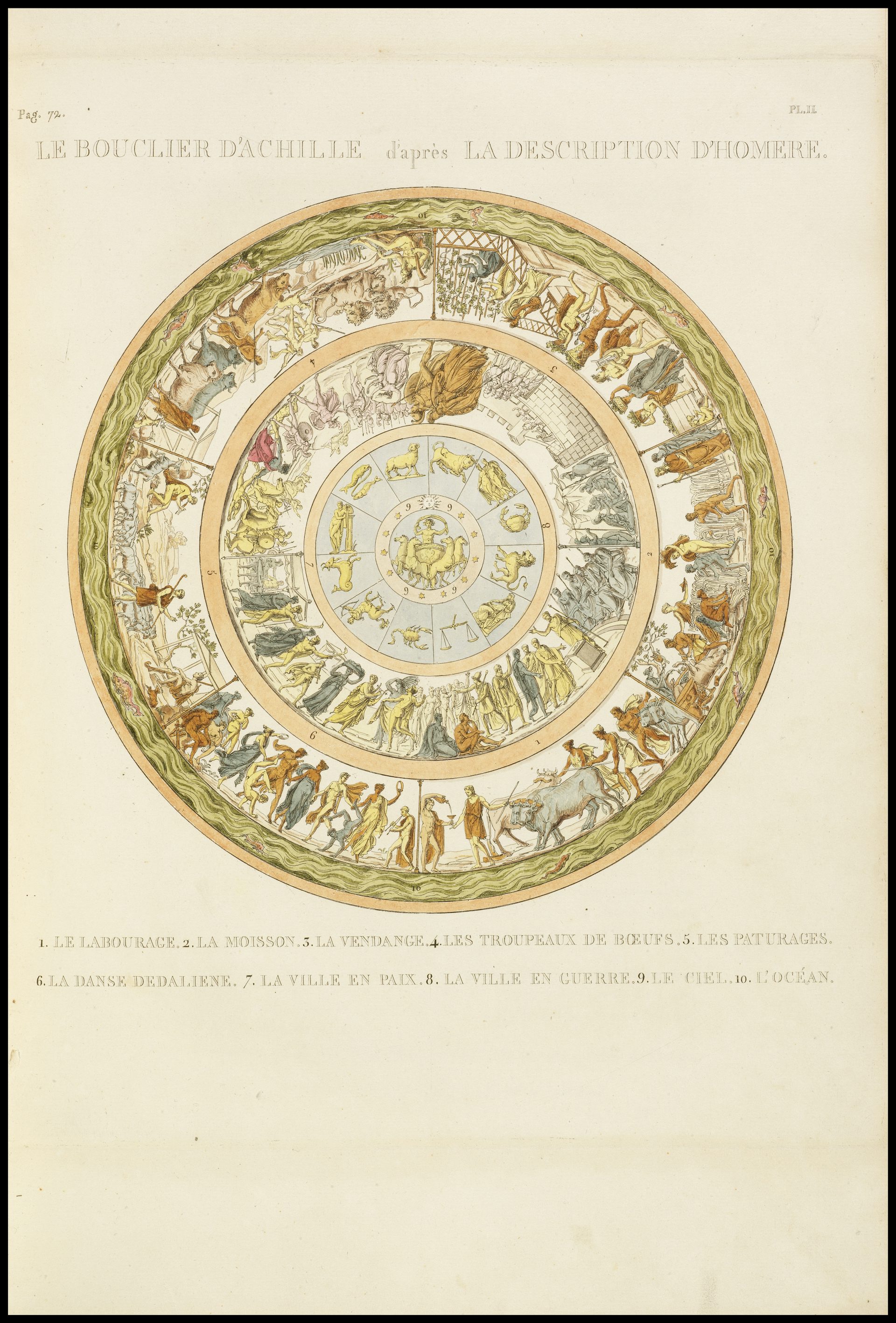

Achilles was typically depicted as a young warrior. In Homer’s epics, he was noted for his physical beauty but also for his armor, fashioned by the god Hephaestus himself. Achilles’ elaborate shield, described by Homer in Book 18 of the Iliad, was especially famous.

Hand-colored etching of the shield of Achilles according to the description of Homer by Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy (1814)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFamily

Achilles’ mother was Thetis, a Nereid. As daughters of the sea god Nereus, the Nereids were goddesses themselves. Achilles’ father, Peleus, was a son of Aeacus and a grandson of Zeus. Peleus was the king of Phthia in northern Greece, while his brother Telamon was the king of the island of Salamis. Telamon’s son and Achilles’ cousin, Ajax, was also one of the mightiest Greek warriors who fought at Troy.

Mythology

Birth

Achilles’ mother, the sea goddess Thetis, was originally courted by the gods Zeus and Poseidon. According to the best-known version of the story, the two gods soon learned from an oracle that Thetis was destined to give birth to a son who would be greater than his father. Neither Zeus nor Poseidon wanted to risk having a child who could overthrow them as they had overthrown their own father, Cronus.[7]

According to another version, however, Thetis had rejected Zeus’ advances because of her loyalty to Zeus’ wife Hera. Zeus was furious and forced Thetis to marry a mortal in order to humiliate her.[8]

In both versions, the gods decided to marry Thetis off to the mortal hero Peleus. But before he could marry Thetis, Peleus had to wrestle with her as she shape-shifted and transformed into water, fire, and various wild animals. Since Peleus was able to hold on to Thetis through all her transformations, the goddess finally consented to marry him.

The wedding of Peleus and Thetis was a grand affair, and all the gods were invited but one: Eris, the goddess of discord. Angry at the slight, Eris attended anyway to stir up trouble. In the middle of the festivities, she produced a golden apple with the inscription “to the fairest.” The goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite all claimed the apple as theirs, and the resulting quarrel ultimately helped start the Trojan War.

When Achilles was born, Thetis wished to make him immortal. There are two main accounts of how she accomplished this. According to Statius’ Thebaid and Hyginus’ Fabulae, she dipped Achilles in the Styx, the river of the Underworld. However, Achilles remained vulnerable in the heel where Thetis had held him.[9]

Thetis dipping Achilles in the River Styx by Thomas Banks (1789).

Victoria and Albert Museum, LondonPublic DomainIn another version, Thetis anointed the infant Achilles with ambrosia by day and held him over the fire by night. But one night Peleus interrupted Thetis during this process and snatched Achilles away in horror. Thetis was furious and abandoned her husband and son, returning to live with the other Nereids in the sea. Since Thetis was unable to complete the procedure, Achilles remained vulnerable in his heel.[10] After Thetis left, Peleus took Achilles to the mountains to be raised by the wise centaur Chiron.

Skyros

According to some late versions of the myth,[11] Achilles was concealed on the island of Skyros by Thetis (or Peleus, in some sources) to protect him from the Trojan War. An oracle had foretold that if Achilles fought in the Trojan War he would be killed. The young Achilles was therefore disguised as a girl and sent to live among the daughters of King Lycomedes of Skyros.

While on Skyros, Achilles fell in love with Lycomedes’ daughter Deidamia. The two had a son in secret, who was later called Neoptolemus but was also given the name Pyrrhus (after Achilles’ alias while on Skyros, Pyrrha).

But the Greeks learned from an oracle that they would be unable to take Troy without Achilles’ help. To trick Achilles out of hiding, the clever Odysseus came to Skyros and presented the daughters of Lycomedes with various gifts, including women’s clothes and jewelry but also a shield and spear. He then had his men feign an attack on the palace. As Odysseus had predicted, Achilles threw off his disguise, grabbed the shield and spear, and braced himself for battle, thus betraying his identity to the Greeks.

Earlier sources have a different version of the story, however. According to Homer, Odysseus and the Pylian king Nestor recruited Achilles at Peleus’ home in Phthia.[12] In the sixth-century BCE epic poem Cypria, which survives only in fragments, Achilles did stop at Skyros on the way to Troy. While there, he married Lycomedes’ daughter Deidamia and fathered Neoptolemus. In the Cypria, as well as in the Homeric epics, Neoptolemus was brought up on Skyros and eventually came to fight at Troy after Achilles’ death.[13]

Sailing to Troy

Before Achilles sailed to Troy, his mother warned him that there were two destinies available to him: if he fought at Troy, he would win undying fame, but he himself would die young; if, however, he stayed at home in Greece, he would lead an obscure but long life. Achilles chose the former, preferring a short but glorious life to a long but unremarkable one. Achilles thus sailed to Troy knowing that he would never come home.

According to Homer, Achilles commanded fifty ships. His army was made up of the Myrmidons, fearsome warriors descended from ants. He was also accompanied by Patroclus, his relative and dearest friend.

Telephus

While Achilles and the Greeks were sailing to Troy, they accidentally landed at Mysia. Thinking they had reached Troy, they fought a bloody battle with the Mysians and their king, Telephus. In the chaos, Achilles wounded Telephus in the thigh with his spear. When the Greeks realized their mistake, they apologized and left Mysia. However, their ships were scattered by a storm, and they were forced to return to Greece to regroup.

Meanwhile, Telephus’ wound would not heal. Learning from an oracle that only the “wounder” could heal him, Telephus sailed for Greece and demanded that Achilles help him. Achilles had no medical knowledge, but Odysseus realized that the wounder the oracle meant was the spear that Achilles had used, not Achilles himself. The Greeks thus used Achilles’ spear to treat Telephus’ injury. After Telephus recovered, he agreed to help guide the Greeks to Troy in return.

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia

After the Greek army had gathered for the second time at the port of Aulis, the fleet was prevented from sailing by adverse winds. Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae and the commander of the Greek army, learned from the prophet Calchas that the winds would only turn if he sacrificed his eldest daughter, Iphigenia, to Artemis.

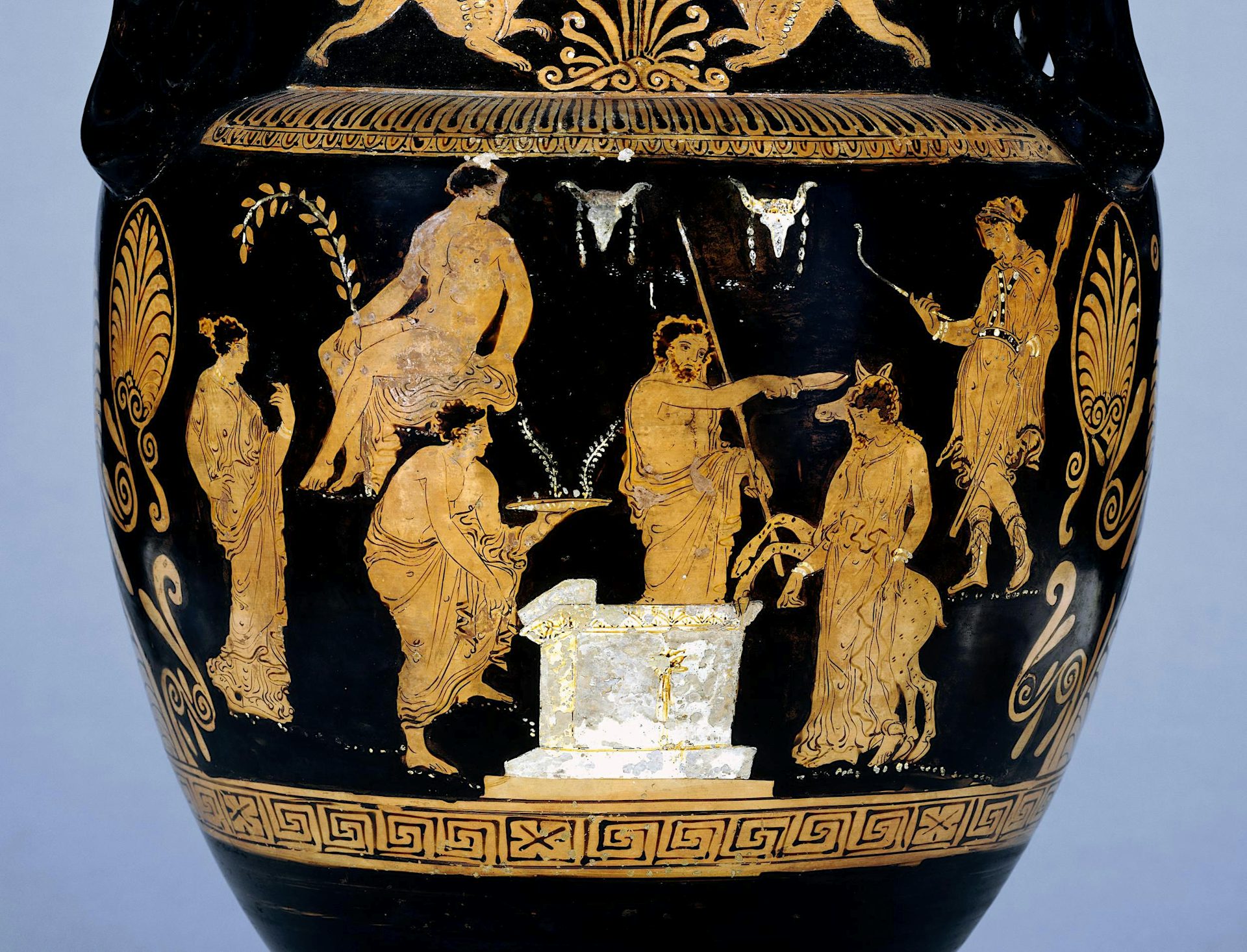

This volute-krater (a bowl used for mixing wine and water) depicts the sacrifice of Iphigenia (c. 370 BCE-350 BCE). At the center is Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae, identified by his scepter. To his right is Iphigenia, with a deer with raised hoofs behind her.

Trustees of the British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0To lure Iphigenia to Aulis, Agamemnon sent a letter in which he claimed that he had promised her to Achilles. When Achilles discovered how his name had been used, he was furious. In Euripides’ tragedy Iphigenia in Aulis (ca. 405 BCE), Achilles even offered to help Iphigenia escape. But Iphigenia refused Achilles’ offer and allowed herself to be sacrificed for the sake of the Greeks.

Tenedos

On their second expedition to Troy, the Greeks raided Tenedos, an island just off the coast of Troy. During the battle, Achilles killed Tenes, a son of Apollo. Because of this, Apollo would forever hate Achilles. According to some sources, Apollo helped Paris kill Achilles as revenge for the death of Tenes.

Trojan War

The Beginning of the War

The Trojan War would ultimately last ten years. After the Greeks landed and set up camp on the beach, they sacked many of the neighboring cities in order to acquire supplies, cattle, and slaves. Achilles was the most successful and vicious of the Greeks; with his army of Myrmidons, he raided countless cities and islands.

During the first years of the war, Achilles killed several Trojan champions, including Cycnus, a son of Poseidon. He also killed Troilus, one of the young sons of the Trojan king, Priam. According to the epic Cypria, Achilles wished to meet Helen, for whom the war was being fought, in person. His mother Thetis arranged for them to meet in secret.

The Rage of Achilles

The most famous and important narrative of Achilles’ actions is the Iliad, which takes place during the ninth and final year of the Trojan War. The Iliad begins with the words:

The wrath sing, goddess, of Peleus' son, Achilles, that destructive wrath which brought countless woes upon the Achaeans, and sent forth to Hades many valiant souls of heroes, and made them themselves spoil for dogs and every bird; thus the plan of Zeus came to fulfillment, from the time when first they parted in strife Atreus' son, king of men, and brilliant Achilles.[14]

The reason for Achilles’ anger was a quarrel he had with Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek army. One day, a priest of Apollo named Chryses came to the Greek camp. He wished to ransom his daughter, who had been taken captive by the Greeks and had become Agamemnon’s slave. When Agamemnon refused to let the girl go, Chryses begged Apollo to avenge him. Apollo, answering Chryses’ prayer, sent a plague to the Greek army.

Eventually, the Greek prophet Calchas revealed that the plague had been caused by Agamemnon’s refusal to release Chryses’ daughter. When Achilles learned of this, he publicly demanded that Agamemnon return the girl to her father. Agamemnon finally agreed to do so, but said that he would take Achilles’ slave girl Briseis as compensation.

Achilles, humiliated, almost killed Agamemnon, but restrained himself and decided instead that he would no longer fight for Agamemnon. He then told his mother, Thetis, of the insult, and Thetis made Zeus promise that he would make the Greeks suffer for insulting Achilles.

In the days that followed, Zeus kept his promise to Thetis. The Greek army began suffering heavy losses at the hands of the Trojans. Hector, the oldest son of Priam and the commander of the Trojan army, was virtually invincible without Achilles to keep him in check.

Eventually, Agamemnon became desperate and begged Achilles to rejoin the fighting, promising to return Briseis in addition to many other treasures. Though Odysseus, Nestor, and Achilles’ cousin Ajax did their best to coax him, Achilles refused to accept Agamemnon’s offer.

The next day, the Greeks continued to suffer heavy losses. Led by Hector, the Trojans advanced into the Greek camp and started burning the Greeks’ ships. Achilles’ close friend Patroclus pitied the Greeks and begged Achilles to help them. Achilles refused, but agreed to let Patroclus put on his terrifying armor and lead the Myrmidons against Hector.

In the battle, Patroclus was able to drive the Trojans away from the Greek camp and even killed Zeus’ son Sarpedon, an important ally of the Trojans. But as he tried to mount an assault on the walls of Troy, Patroclus was killed by Hector with the help of Apollo.

When Patroclus fell, Hector and the Trojans immediately realized that he was not Achilles—he was merely wearing his friend’s famous armor. Hector stripped the armor from Patroclus, but after a fierce battle, the Greeks managed to carry his body back to their camp.

When Achilles saw his fallen friend, he was heartbroken. He wanted to fight Hector immediately, but Thetis made him wait until she could bring him a new set of armor fashioned by the smith god Hephaestus.

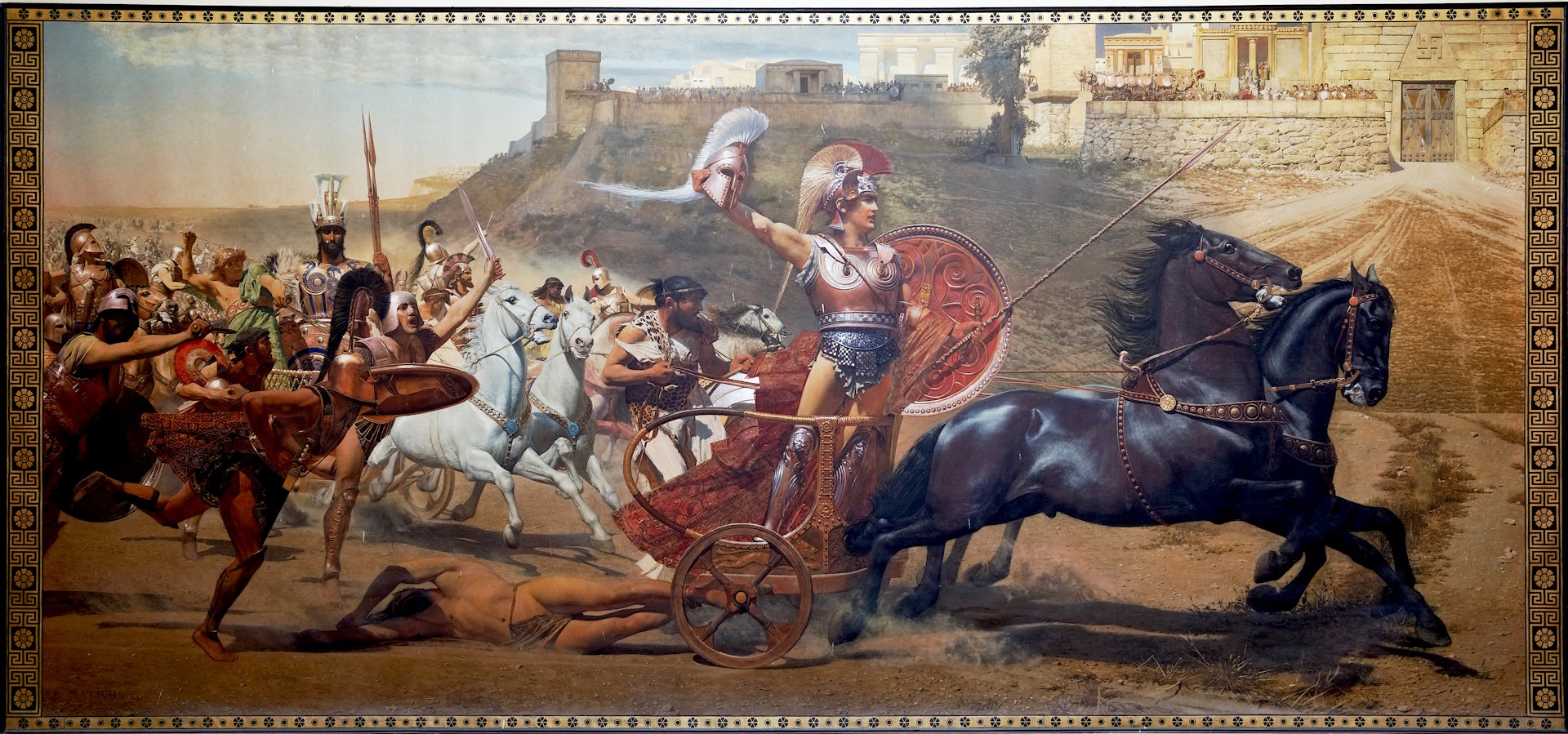

The next day, Achilles put on his new armor and led the Greeks against Troy. After slaughtering many Trojans, Achilles finally met Hector in single combat and killed him. He then lashed Hector’s body to his chariot and dragged him three times around the walls of Troy before returning to camp.

The Triumph of Achilles by Franz von Matsch (1892), a fresco at Achilleion palace in Corfu, Greece.

Eugene RomanenkoCC BY 2.0Achilles wanted to leave Hector’s body to the dogs and vultures, but after twelve days Hector’s father, Priam, the king of Troy, came secretly to the Greek camp to ransom Hector’s body. In Homer’s Iliad, Priam kissed Achilles’ hands and said,

[I] have endured what no other mortal on the face of earth hath yet endured, to reach forth my hand to the face of him that hath slain my sons.[15]

Achilles was touched by Priam’s bravery and let him take Hector’s body for a proper burial.

Penthesilea and Memnon

Following Hector’s death, the Trojans received aid from the Amazons. The Amazons were a race of warrior women who claimed to be descended from the war god Ares. Penthesilea, the queen of the Amazons, fought bravely against the Greeks but was finally killed by Achilles. When Achilles saw the beautiful Amazon lying dead, however, he pitied his victim. One Greek warrior, Thersites, saw Achilles weeping over Penthesilea’s body and jeered at him. This further angered Achilles and he struck Thersites, killing him instantly.

The Trojans next received aid from Memnon, the king of the Ethiopians. Memnon was the son of Eos, the goddess of dawn, and the Trojan prince Tithonus: he was thus related to Priam and his family by blood. In battle, Memnon killed Antilochus, the son of the wise old king Nestor.

Like Patroclus, Antilochus had been a close companion of Achilles, and Achilles vowed revenge when he found out about his death. Achilles fought and killed Memnon, causing Dawn herself to go into hiding.

Death

There are several different versions of the death of Achilles. The best-known story is that Achilles was shot and killed by Paris, the Trojan prince who started the war by carrying off Helen. In some sources, Paris’ arrow was guided by the god Apollo himself.[16] In the earliest versions of the story, this took place immediately following Memnon’s death: after Memnon had fallen, Achilles pursued the Trojans to their walls and was shot by Paris with the help of Apollo.[17]

Wounded Achilles by Filippo Albacini (1825). From the Devonshire Collections at Chatsworth House in the UK, the marble statue traveled to the British Museum as part of an exhibit titled Troy: Myth and Reality.

Jamie HeathCC BY-SA 2.0But in another version of the story, known only from much later sources, Achilles fell in love with the Trojan princess Polyxena and asked Priam for her hand in marriage. When Achilles came to Troy to marry Polyxena, however, he was ambushed and killed by Paris.[18] The myth of “Achilles’ heel” was probably a later invention: in most early accounts, Achilles was shot or stabbed in the torso.[19]

The Armor of Achilles

After Achilles had been buried, his splendid armor became the object of a dispute between Odysseus and Ajax. Each of the two heroes believed that he was the greatest of the Greeks after Achilles and therefore deserved to inherit his armor. The other Greeks eventually decided to award the armor to Odysseus.

Ajax, enraged at this decision, plotted to kill Odysseus and the other Greek commanders under cover of night. But Athena, Odysseus’ patron goddess, drove Ajax mad and caused him to attack the Greeks’ livestock: as Ajax slaughtered sheep, cows, and goats, he imagined that he was murdering Odysseus and his companions. At daybreak, Ajax regained his senses; realizing what he had done, he killed himself in shame.

The Sacrifice of Polyxena

After the Greeks finally captured and sacked Troy, they took the Trojan queen Hecuba and many of her daughters prisoner. Most of these royal captives became slaves of the various Greek kings.

The Sacrifice of Polyxena by Charles Le Brun (1647).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBut before the Greeks could sail back home, the ghost of Achilles came to them and demanded that Polyxena, one of Hecuba’s younger daughters, be awarded to him. The Greeks, fearing Achilles even in death, respected his wishes. Polyxena was sacrificed to Achilles’ ghost at Achilles’ own tomb.

Afterlife

The stories told about Achilles’ afterlife are varied and sometimes contradictory. In Homer’s Odyssey, the hero Odysseus spoke to Achilles in the Underworld on his way home from Troy. During this meeting, Achilles asked Odysseus for news about his family and especially about his son Neoptolemus.

Odysseus explained that Neoptolemus had fought with the Greeks at Troy following his father’s death and had distinguished himself when the city was finally conquered. When Odysseus commented that Achilles commanded respect even among the dead, the shade of the hero replied:

Nay, seek not to speak soothingly to me of death, glorious Odysseus. I should choose, so I might live on earth, to serve as the hireling of another, of some portionless man whose livelihood was but small, rather than to be lord over all the dead that have perished.[20]

In other traditions, however, Achilles enjoyed a more glorious afterlife, living in eternal bliss in a place called the White Isle, Elysium, or the Isles of the Blessed.[21] According to this version, Achilles was married to a royal figure in the afterlife—often Medea, but sometimes Polyxena or even Helen.

Worship

Festivals and/or Holidays

Achilles was celebrated and honored throughout the Greek world. Every year, the Thessalians sent representatives to the Troad, the peninsula in which Troy was located, to offer sacrifices to Achilles.[22] There was also a cenotaph (a memorial or “empty tomb”) of Achilles in Olympia, where ceremonies were performed in honor of the hero before the commencement of each Olympic Games.[23]

Temples

There were temples of Achilles scattered throughout the Greek world, though most were clustered around the Black Sea. One major temple, called the Achilleum, was in the Troad near the spot where Achilles was thought to be buried.[24] In the Pontus region, near the Black Sea, Achilles also had sanctuaries at the Milesian colony of Olbia, at Achilleos Dromos,[25] and on the island of Leuke on the mouth of the river Ister.[26]

Achilles was also worshipped under the name Pontarches as a protector of sailors.[27] Outside of the Black Sea, Achilles had sanctuaries and temples on the island of Astypalaea in the Sporades;[28] in Elis; in Phthia, Achilles’ homeland in northern Greece; in Sparta;[29] and throughout southern Italy in Tarentum, Locri, and Croton.

Pop Culture

Achilles and his myth have had a very prolific afterlife in modern pop culture. Achilles features as a main character in many modern novels, including Colleen McCullough’s The Song of Troy (1998), Elizabeth Cook’s Achilles: A Novel (2001), David Gemmell’s Troy series (2005–2007), and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls (2018). In Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles (2011), which won the 2012 Orange Prize for Fiction, the myth of Achilles is narrated from the perspective of Patroclus.

Achilles has also been portrayed in film and television. In the 2004 film Troy, Achilles was played by Brad Pitt. More recently, David Gyasi played Achilles in the 2018 television series Troy: Fall of a City.

Achilles also appears in Eric Shanower’s Age of Bronze (1998–), an ongoing graphic novel series that retells the myth of the Trojan War.