Helen of Troy

Overview

The woman who came to be known as Helen of Troy was actually born Helen of Sparta. She was the daughter of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Leda, a mortal woman and the wife of the Spartan king Tyndareus. Helen’s siblings included the heroic twins Castor and Polydeuces (also known as the Dioscuri) and the murderous Clytemnestra.

Helen quickly became known as the most beautiful woman in the world. She had so many suitors that her foster father Tyndareus feared a war would erupt over her hand. Sure enough, when Helen left her Greek husband Menelaus for the handsome Trojan prince Paris, war did break out: the Greeks fought the Trojans for ten long years to get Helen back.

Ever since antiquity, poets, readers, and scholars have offered contradictory interpretations of Helen. Some have seen her as haughty and vain, others as romantic and long-suffering. There were even versions of the myth in which Helen remained loyal to Menelaus and did not sail to Troy at all. Even today, few characters from Greek mythology capture the imagination as much as the perpetually ambiguous Helen of Troy.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Helen” (Greek Ἑλένη, translit. Helénē) continues to be debated.[1]

One school of thought derives Helen’s name from Greek or Indo-European root words referring to the light of celestial bodies—for example, the Sanskrit svaraṇā, meaning “the shining one.” Scholars seeking an Indo-European origin for Helen have compared her story to that of the Hindu deity Saranyu, who, like Helen, ran away from her husband (the sun god Surya). Thus, Helen might have originally been connected with goddesses of the sun or moon, such as the Greek Selene.[2]

A different approach has linked Helen to Venus, the Roman counterpart of the Greek Aphrodite. According to this view, the lambda in Helen’s name was originally a nu, while the first letter was a digamma, meaning that her name (transliterated) was originally “Wenena”—a variation of the Latin Venus.[3]

Other scholars have connected Helen’s name with the Greek word ἑλένη (helénē; alternatively spelled ἑλάνη, helánē), which can mean either “torch” or “basket,” and with ἑλένιον (helénion), a kind of plant.[4]

Alternatively, Helen has been interpreted by some as an early vegetation deity.[5] Lily Clader, seeking to combine these different etymologies, argued that the vegetation goddess who eventually became Helen got her name from the wicker baskets—ἑλέναι (helénai) in Greek—that were used during her festival.[6]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Helen Ἑλένη (translit. Helenē) Phonetic

IPA

[HEL-uhn] /ˈhɛl ən/

Titles and Epithets

Helen’s most famous title was “Helen of Troy,” but she was also “Helen of Sparta”; Sparta was, after all, her birthplace and where she ruled as queen for many years before fleeing to Troy with Paris.

Helen had numerous other epithets as well—so many, in fact, that an entire book has been written about them.[7] One of her most common epithets was Argeiē (“Argive”), a reference to her place of origin in the neighborhood of the Peloponnesian city of Argos. Other epithets, such as kourē Dios and Dios ekgegauia (“daughter of Zeus”), referred to her divine parentage. Finally, Helen boasted many epithets that described her beauty, including leukōlenos (“white-armed”), dia (“brilliant”) or dia gynaikōn (“brilliant among women”), ēukomos or kallikomos (“fair-haired”), and kalliparēios (“fair-cheeked”).

Attributes and Iconography

Beauty

Helen’s signature attribute was her beauty. Known as the most beautiful woman in the world, just one glance from Helen was enough to make men forget their better judgment. The devastating consequences of Helen’s looks were perhaps most memorably captured in the words of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus:

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?[8]

Helen of Troy by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1863). Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAncient sources constantly mentioned Helen’s beauty with awe, but rarely described it with anything more than formulaic epithets (“fair-haired,” “fair-cheeked,” etc.). There are a few exceptions. Dares of Phrygia, for example, in a sixth-century BCE prose work that claimed to be an eyewitness account of the fall of Troy, had this to say of Helen’s appearance and personality:

She was beautiful, ingenuous, and charming. Her legs were the best; her mouth the cutest. There was a beauty-mark between her eyebrows.[9]

In most sources, however, it was the effects of Helen’s looks that were most notable. In one tradition, for example, Menelaus was ready to kill his adulterous wife by the time Troy finally fell; but a single glimpse of her was enough to make him drop his weapon and take her back home to be his wife again, letting bygones be bygones.

Personality

Beyond her looks, Helen had a powerful, if contradictory, personality.[10] In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the earliest surviving texts to represent her as a character, Helen can be astonishingly self-aware and even self-deprecating, expressing regret for sailing off with Paris and even referring to herself as a “dog.”[11] On the other hand, Homer’s Helen is also deceitful and manipulative, as when she tries to trick the Greeks inside the Trojan Horse into giving themselves away to the Trojans.[12]

Helen’s enigmatic nature persisted in the works of Greek and Roman writers after Homer. Some condemned her for her adultery and for starting the Trojan War. Aeschylus, for example, characterized Helen as “that bride of the spear and source of strife,” continuing punningly that “true to her name, a Hell she proved to ships, Hell to men, Hell to city.”[13]

On the other hand, some authors devised creative ways to exonerate Helen: in the fifth century BCE, for example, the sophist Gorgias reasoned that, even if Helen had not been carried off by physical force and succumbed instead to love, lust, or persuasion, she should still be regarded as a victim of compulsion.[14]

In another twist, there was also an alternative tradition in which Helen never betrayed her husband Menelaus at all but was instead replaced in Troy by a phantom look-alike (see below).

Iconography

Helen was often represented in ancient art. Numerous vase paintings show her as an alluring and well-proportioned young woman. Yet her famous beauty was difficult to capture: it was said that the fifth-century BCE painter Zeuxis wished to portray Helen but was unable to find a model who was beautiful enough. He solved the problem by combining the best features of five different women.[16]

Zeuxis Choosing his Models by Victor Mottez (1858).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFamily

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mothers

- Leda

- Nemesis

Siblings

Brother

Sisters

- Clytemnestra

- Philonoe

- Phoebe (daughter of Tyndareus)

- Timandra

Consorts

Husbands

Lover

Children

Daughters

Sons

- Aethiolas

- Aganus

- Bunomus

- Corythus

- Idaeus

- Maraphius

- Nicostratus

- Pleisthenes

Mythology

Origins

In the most familiar tradition, Helen was born after Zeus, the ruler of the Greek gods, seduced Leda, the wife of King Tyndareus of Sparta. As part of this seduction, Zeus transformed himself into a swan; when an eagle began to chase him, he flew to Leda for refuge. He then slept with Leda—still in the form of a swan!—and departed, leaving the queen of Sparta pregnant.[30]

Leda and the Swan by Cesare de Sesto after Leonardo da Vinci (ca. 1505–1510). Wilton House, Salisbury, UK.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFrom here, the story gets even stranger. After sleeping with Zeus, Leda also slept with her husband Tyndareus and became pregnant by him, too. When it came time for her to give birth, Leda laid an egg (or two, in some traditions), from which emerged not only Helen but also Clytemnestra, Castor, and Polydeuces.[31] Most sources made Helen and Polydeuces the children of Zeus, and Clytemnstra and Castor the children of Tyndareus.[32]

In another tradition, Helen was the daughter not of Zeus and Leda but of Zeus and Nemesis. Usually described as the daughter of the primordial deity Nyx,[33] Nemesis was the divine embodiment of retribution. In trying to flee Zeus’ advances, Nemesis transformed herself into various animals, the last of which was a goose; Zeus in turn transformed himself into a goose or a swan (there are different versions) and raped her. Nemesis subsequently became pregnant and laid an egg, which came into Leda’s possession. When Helen hatched from it, she was raised by Leda and Tyndareus as though she were their own daughter.[34]

Abduction by Theseus

Even at a very young age, Helen’s beauty brought her unwanted attention. When she was still just a child—in some sources as young as seven years old,[35] in others ten[36] or twelve[37] years old—Helen was abducted by the Athenian hero Theseus, who wanted to marry the daughter of a god. He was helped in this plot by his close friend Pirithous.

Theseus then left Helen with his mother Aethra while he helped Pirithous abduct a divine wife of his own. Their target this time was Persephone, the queen of Hades. Ultimately, this turned into a fiasco, and Theseus and Pirithous became trapped in the Underworld.

While Theseus and Pirithous were gone, Helen’s brothers Castor and Polydeuces came to rescue her. They ransacked Athens and captured Theseus’ mother Aethra in revenge. As punishment for her son’s misdeeds, Aethra was forced to become Helen’s servant—a post she occupied for many years.[38]

In some traditions, Helen was of childbearing age when Theseus abducted her and actually bore him a daughter named Iphigenia. When Helen returned to Sparta, she gave Iphigenia to her sister Clytemnestra to raise. Later, Iphigenia was sacrificed by Clytemnestra’s husband Agamemnon so that the Greeks could appease the gods and sail to Troy.[39]

The Suitors and the Oath of Tyndareus

When Helen came of age to be married, the most eligible young men (and some not-so-young ones) came from far and wide to seek her hand. But Tyndareus feared that by choosing one man as Helen’s husband, he would offend the others, and that the unsuccessful suitors would subsequently wage war against the successful one—or against Tyndareus.

Helen of Troy by Evelyn de Morgan (1898).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainLuckily, the hero Odysseus, well known for his cunning, devised a plan to deliver Tyndareus from his plight. Though Odysseus had come to Sparta with the other suitors, he knew that his poor kingdom of Ithaca would not be enough to win him Helen’s hand. He therefore promised Tyndareus a solution to his problem if he would help Odysseus in his suit for Helen’s cousin Penelope.

Odysseus’ solution was simple: Tyndareus would make all the suitors swear an oath to support Helen’s chosen husband against anyone who might quarrel with him. Tyndareus promptly agreed, and the suitors all swore what came to be known as the Oath of Tyndareus. Menelaus was then named as Helen’s husband (whether it was Tyndareus or Helen who chose him varies among ancient sources).[40]

In most traditions, Tyndareus stepped down from the throne after Helen was married, and Menelaus became ruler of Sparta in his place.[41] Menelaus and Helen had several children together, the most famous being a daughter named Hermione.

Paris

After Helen had been living as Menelaus’ wife for some time, the handsome Paris came to Sparta on a diplomatic mission. Paris was a prince from Troy, a rich city by the Hellespont (the narrow strait between Asia and Europe), on the northwestern coast of modern Turkey.

Prior to his voyage, Paris had been tasked with judging a beauty contest between three powerful goddesses: Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. The winner of this contest was to receive a golden apple inscribed with the words “to the fairest.” Each goddess attempted to bribe Paris, but it was Aphrodite’s bribe that won him over: she promised that if Paris picked her, she would grant him the love of Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris thus gave Aphrodite the golden apple and went to Sparta to collect his reward.[42]

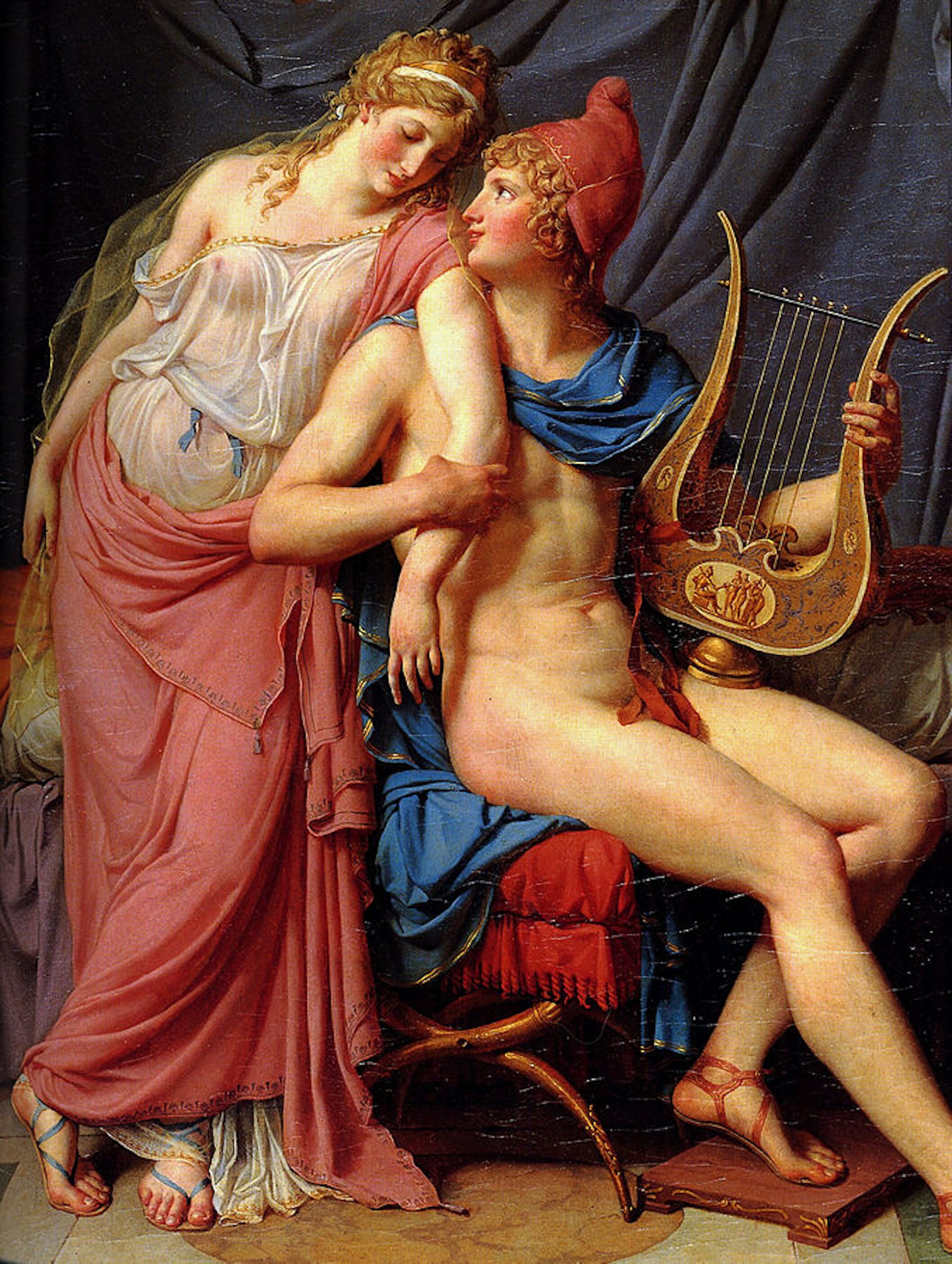

Helen and Paris by Jacques-Louis David (1788). Louvre Museum, Paris.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainIn the most familiar sources for the myth, Helen went with Paris willingly, won over by his charm and good looks.[43] According to some authors, however, Paris raped Helen and took her to Troy against her will.[44] Other ancient sources were evasive about whether she chose to leave or was carried off by force.

A Variant Tradition: Helen in Egypt

To make matters even more confusing, there was an alternative tradition (known from works by Stesichorus, Herodotus, and Euripides) in which Helen did not go to Troy at all.[45]

According to Euripides (and probably Stesichorus, whose work on the subject no longer survives), Helen was replaced by a kind of phantom (called an eidōlon in Greek) that resembled her perfectly. It was this false Helen that Paris carried off with him to Troy; the real Helen, meanwhile, was spirited away to Egypt.

Menelaus, thinking Helen had gone to Troy, assembled the Greeks and fought the Trojans for ten long years, not knowing his efforts were for a mere phantom. Only after Troy had been sacked did Menelaus happen upon the real Helen on his way back home, while making a detour through Egypt. According to this variant, then, the whole Trojan War had been fought in vain.[46]

Herodotus’ version of this myth is, if anything, even bleaker. According to Herodotus (who claimed to have learned his version from Egyptian priests), Helen was carried off by Paris during his visit to Sparta. But during a stop at Egypt, the Egyptian King Proteus realized what Paris had done and forced him to leave Helen in Egypt until her true husband Menelaus could come for her.

Meanwhile, the Greeks sailed to Troy and demanded that Helen be returned to them. When the Trojans explained that they did not have her, the Greeks did not believe them and went to war with the city. Ten years later, with Troy in ruins, the Greeks finally realized the Trojans had been telling the truth, and Menelaus managed to retrieve Helen from Egypt.[47]

The Trojan War

When Menelaus realized that Paris had left Sparta with Helen in tow, he called on all of Helen’s old suitors to fulfill their oath. The suitors slowly came from every corner of Greece to support Helen’s marriage to Menelaus, just as they had sworn to do years before. Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae and the most powerful of the Greeks, was appointed the leader of the expedition. According to the most popular version of the myth, over one thousand ships gathered to sail against Troy.[48]

Agamemnon and Menelaus suffered numerous setbacks at the outset of their expedition, including several Greeks who did not wish to participate (among them, the famous hero Achilles), an accidental landing at Mysia (just south of Troy), and cataclysmic storms. At one point, Agamemnon angered the goddess Artemis and was forced to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia (who in some traditions was really the daughter of Helen and Theseus; see above) in order to appease her. Only after this sacrifice were the Greeks able to sail to Troy.[49]

When the massive Greek army finally landed at Troy, they first sent a delegation to the Trojans—made up of Helen’s husband Menelaus and the crafty Odysseus, among others—to request that Helen be returned. When the Trojan king Priam steadfastly refused, the Trojan War at last began.

During the war, Helen remained in Troy as Paris and the other Trojan warriors fought to defend their city against the Greeks. Though Priam and his son Hector, the commander of the Trojan army, were kind to Helen, few other Trojans were. All the same, Helen was an object of wonder and awe in Troy. Homer reports the words spoken by the Trojan elders when they saw Helen on the walls of Troy:

Small blame that Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans should for such a woman long time suffer woes; wondrously like is she to the immortal goddesses to look upon. But even so, for all that she is such an one, let her depart upon the ships, neither be left here to be a bane to us and to our children after us.[50]

The war raged for ten years. In the ninth year, Menelaus and Paris agreed to settle the matter once and for all in single combat, but Aphrodite saved Paris’ life after Menelaus won. Thus, the war continued.

Helen on the Ramparts of Troy by Frederic Leighton (1865).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainSome time later, Paris was killed by Philoctetes with the poisoned arrows that had once belonged to Heracles. Yet the Trojans still would not return Helen to Menelaus; instead, Helen was given as a wife to Paris’ brother Deiphobus.

The Fall of Troy

True to her nature, Helen appears to have played a contradictory role in the fall of Troy.

In one tradition, Helen helped Odysseus when he snuck into Troy as a spy during the last year of the war. It was said that he was on a mission to retrieve the Palladium, an ancient statue that guaranteed invincibility to whomever possessed it. As long as the Palladium was in Troy, the Greeks could not hope to conquer the city. By hiding Odysseus, Helen made it possible for him to steal the Palladium and effectively sealed Troy’s fate.[51]

In the end, the Greeks decided to take Troy by trickery rather than force and built a giant, hollow wooden horse—the so-called Trojan Horse. When it was finished, a handful of the bravest and strongest Greek warriors hid inside while the rest of the Greeks sailed away. The Trojans, thinking it was some kind of gift, carried the massive construction into their city. But Helen realized that there were Greek warriors hiding within the horse.

There are different versions of what she did with this information. In one version, Helen decided to help the Greeks. When night had fallen, she led the Trojan women with blazing torches in pretend religious rites. She then used the torches to signal the rest of the Greek army from the central tower of Troy.[52]

In another version, Helen decided to help the Trojans. As the Trojans set up the wooden horse in the heart of the city, Helen tried to lure the Greek warriors out of hiding by calling on each of them with the voices of their loved ones. The homesick Greeks very nearly replied and gave away their position. If they had, they would have been massacred, and Troy would have won the war.[53]

The Greeks’ plan ultimately worked: when the Trojans were asleep, the warriors in the horse opened the gates and let in the rest of their army, which had sailed back to Troy in the night. They then sacked the city. Helen’s husband Deiphobus was killed, and Helen was dragged back to the Greek camp.

Many traditions tell of how Helen was nearly killed for her treachery after falling into the hands of the Greeks. In one version, it was Menelaus himself who wanted to kill her. But just one look at her softened him: he was overwhelmed by her beauty and dropped his sword.[54]

In another version, a crowd of Greeks and captive Trojans gathered around Helen to stone her to death. But they, too, were overwhelmed by her beauty and let the stones drop from their hands.[55] In only one version—dramatized in Euripides’ Trojan Women—did Menelaus actually put Helen on trial and announce that she would face a death sentence once she had been taken back to Greece.[56]

Attic red-figure krater depicting Menelaus intending to kill Helen but dropping his sword as soon as he sees her beauty. Attributed to the Menelaus Painter, from 450–440 BCE.

JastrowPublic DomainReturn to Greece

Helen went back to Sparta with Menelaus. Due to bad weather and other misfortunes, it took the couple seven years to complete the return journey. During their wanderings, they spent time in Egypt.

There are different versions of what happened to Helen and Menelaus once they returned home. In the earliest known tradition, the one described in Homer’s Odyssey, Helen and Menelaus resumed living as a married couple. When Telemachus comes to visit, Menelaus explains that while he was in Egypt he had learned his destiny from the prophetic Proteus, who had said to him:

for thyself, Menelaus, fostered of Zeus, it is not ordained that thou shouldst die and meet thy fate in horse-pasturing Argos, but to the Elysian plain and the bounds of the earth will the immortals convey thee, where dwells fair-haired Rhadamanthus, and where life is easiest for men. No snow is there, nor heavy storm, nor ever rain, but ever does Ocean send up blasts of the shrill-blowing West Wind that they may give cooling to men; for thou hast Helen to wife, and art in their eyes the husband of the daughter of Zeus.[57]

While Menelaus was destined to spend the afterlife in Elysium (or, in other sources, the Isles of the Blessed), many claimed that Helen was transformed into a goddess after her death.[58] In some traditions, she became the wife of Achilles in the afterlife. The couple lived together in eternal bliss on the White Isle, a remote paradise reserved for deified mortals.[59]

Other traditions were more violent. In Euripides’ Orestes, Helen becomes the target of an assassination attempt as soon as she arrives in Greece. Orestes, Menelaus’ nephew, decides to kill Helen for her role in causing the Trojan War and to punish Menelaus for not being more supportive. But at the last moment, Helen is saved by Apollo, who turns her into a goddess.[60]

In a different tradition, Helen was exiled from Sparta after Menelaus had died. She went to Rhodes, where she was taken in by her old friend Polyxo. But Polyxo had come to hate Helen because her own husband, Tlepolemus, had died during the Trojan War. Thus, Polyxo dressed up several handmaidens as Furies and had them hang Helen from a tree.[61]

Worship

Festivals and Holidays

Helen’s worship was strongly associated with choruses of young women. These choruses probably played an important role in festivals of Helen, performing choreographed dances and participating in footraces.[66]

Temples

In Sparta, Helen had two important temples. One was in the area known as Platanistas, south of the main town and close to the banks of the Eurotas, the river that ran by Sparta.[67] The second temple was on the opposite bank of the Eurotas, in Therapne.

Remains of the Menelaion in Therapne.

Heinz-SchmitzCC BY-SA 2.5Helen’s shrine at Therapne, called the Menelaion, is perhaps the better known of the two. It was there that Helen and Menelaus were believed to have been buried after they died.[68] The Menelaion at Therapne was thus regarded as a very ancient and important cult site of Helen of Troy. In one story, told by the historian Herodotus, the third wife of the Spartan king Ariston was transformed from remarkably ugly to remarkably beautiful through Helen’s intervention at Therapne.[69]

In Athens, Helen seems to have been worshipped in connection with her brothers, Castor and Polydeuces (the Dioscuri).[70]

In Rhodes, there was a sanctuary dedicated to Helen Dendritis, “Helen of the Tree.” It was said that the sanctuary was built after Polyxo had Helen murdered in Rhodes.[71]

Pop Culture

Helen of Troy’s hold on the public imagination has continued virtually uninterrupted to the present day, inspiring countless books, films, television shows, and artistic pieces.

In literature, Helen has been the protagonist of such novels as John Erskine’s The Private Life of Helen of Troy (1925), Amanda Elyot’s The Memoirs of Helen of Troy (2006), and Margaret George’s Helen of Troy (2006). She also appears in poems by Oscar Wilde, William Butler Yeats, Andrew Lang, H. D., and Margaret Atwood.

On the stage, Helen has inspired works from Richard Strauss’ opera The Egyptian Helen (1928) to Jacob M. Appel’s Helen of Sparta (2008).

Helen has also enjoyed wide appeal in film and television. She is a central character in the 1956 film Helen of Troy, the 1971 film The Trojan Women (an adaptation of a tragedy by Euripides), the 2003 miniseries Helen of Troy, the 2004 film Troy, and the 2018 miniseries Troy: Fall of a City.

In modern adaptations, Helen has remained an equivocal and divisive figure. She is sometimes represented as faithless, vain, and fickle, and other times praised for her willingness to sacrifice everything for love. This endless back and forth is no doubt a central reason for our enduring fascination with Helen.