Agamemnon

The Feast of Atreus and Thyestes by Václav Jindřich Nosecký and Michael Václav Halbax (ca. 1700)

Zákupy Castle / Martin MádlCC BY-SA 3.0Overview

Agamemnon, son of Atreus, was the king of Mycenae (or Argos, in some traditions) and the most powerful king of mythical times. When his brother’s wife Helen ran off with a handsome prince from Troy, Agamemnon raised an immense army to get her back.

Agamemnon would stop at nothing to win the glory of conquering Troy, even sacrificing his own daughter Iphigenia in exchange for a favorable wind for his fleet. Though Agamemnon did finally sack Troy after a ten-year war, he was not able to enjoy his glory for long. As soon as he returned home, he was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus.

Who were Agamemnon’s parents?

Agamemnon was the son of Atreus, the king of Mycenae, and his wife Aerope. His brother was Menelaus, king of Sparta and husband of the infamous Helen.

Atreus was embroiled in a lifelong rivalry with his own brother, Thyestes. Both men committed terrible atrocities against one another: in one myth, Thyestes slept with Atreus’ wife Aerope, and Atreus retaliated by killing Thyestes’ children and feeding them to him. These horrific acts spawned the “curse of Atreus,” which plagued not only Atreus but also his children, Agamemnon and Menelaus.

The Feast of Atreus and Thyestes by Václav Jindřich Nosecký and Michael Václav Halbax (ca. 1700)

Zákupy Castle / Martin MádlCC BY-SA 3.0Which city did Agamemnon rule?

In the Homeric epics (the Iliad and the Odyssey), Agamemnon is named as the king of Mycenae, a well-fortified city in the Peloponnese that was important in the earliest periods of Greek history. Mycenae was famous for its commanding fortress built of enormous stone slabs.

By the Classical period, however, Mycenae had lost all of its former power, and some authors reimagined Agamemnon as the ruler of Argos, a city near Mycenae that was an important power in their own day. Eventually, Mycenae and Argos became virtually interchangeable in Greek literature as the kingdom of Agamemnon.

Gold death mask known as the "Mask of Agamemnon" (ca. 1550–1500 BCE), discovered in Mycenae by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876

National Archaeological Museum of Athens / Xuan CheCC BY 2.0How did Agamemnon die?

Agamemnon was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus as soon as he returned home from Troy. In what eventually became the standard tradition, Clytemnestra was angry at Agamemnon for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia in exchange for a wind to blow the Greek fleet to Troy.

When Agamemnon arrived home, Clytemnestra invited him to a bath she had prepared for him. She then trapped him in a net or towel and butchered him with the help of Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin and her lover. With Agamemnon dead, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus made themselves the rulers of Mycenae.

Clytemnestra after the Murder by John Collier (1882)

Guildhall Art Gallery, LondonPublic DomainThe Quarrel of Agamemnon and Achilles

During the Trojan War, Agamemnon often clashed with Achilles, the greatest Greek hero of his generation. Their fiercest quarrel, described at the beginning of the Iliad, began when Agamemnon was forced to return his female captive Chryseis. Chryseis’ father was a priest of Apollo, and as long as Agamemnon kept Chryseis as his concubine, Apollo caused a terrible plague to devastate the Greek camp.

Agamemnon, angry and humiliated at having to give up his concubine, recklessly declared that he would take Achilles’ concubine Briseis as compensation. This made Achilles furious. He almost killed Agamemnon, but then decided to simply quit the war instead.

With Achilles’ withdrawal, the Greeks lost their best fighter and consequently suffered heavy losses at the hands of the Trojans. In the end, though, Agamemnon and Achilles reconciled their differences. Achilles returned to the fighting, and the Greeks eventually won the war.

Fresco from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii showing Achilles and Briseis (1st century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainEtymology

The etymology of the name “Agamemnon” is uncertain. In antiquity, it was sometimes thought to mean “long-remaining,” deriving from the Greek words agan (“very, a long time”) and menein (“to remain”).[1] According to modern scholars, however, the name is derived from either the Greek verb medesthai, meaning “to think on, plan,” or the Greek noun menos, meaning “strength, might.”[2]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Agamemnon Ἀγαμέμνων Phonetic

IPA

[ag-uh-MEM-non, -nuhn] /ˌæg əˈmɛm nɒn, -nən/

Alternate Names

Some variants of the name “Agamemnon” are known from antiquity, mostly from Attic vases. These include Agamesmōn, Agammemōn, and Agamen(n)ōn.

Titles and Epithets

Agamemnon laid claim to a number of important epithets in Greek literature. These include anax andrōn, “lord of men”; eury kreiōn, “wide-ruling”; and poimēn laōn, “shepherd of the people.” Agamemnon was often also known by his patronymic, Atreidēs, meaning “son of Atreus.”

Attributes

Kingdom

Agamemnon was a powerful king. In the earliest sources, he ruled over the city of Mycenae and its surroundings. Homer laid out the extent of Agamemnon’s impressive dominion in the Iliad:

And they that held Mycenae, the well-built citadel, and wealthy Corinth, and well-built Cleonae, and dwelt in Orneiae and lovely Araethyrea and Sicyon, wherein at the first Adrastus was king; and they that held Hyperesia and steep Gonoessa and Pellene, and that dwelt about Aegium and throughout all Aegialus, and about broad Helice,—of these was the son of Atreus, lord Agamemnon.[3]

Mycenae, a fortified city in the northeastern Peloponnese, was an extremely important political and cultural center during the Greek Bronze Age (sometimes also referred to as the “Mycenaean period”), lasting from ca. 1600–1100 BCE. It is particularly famous for its distinctive fortifications, built of tightly-fitted boulders (also known as “Cyclopean masonry”), and its imposing Lion’s Gate—all of which still stand today.

The Lion Gate in Mycenae (erected ca. 1250 BCE). Mycenae, Greece.

Andy HayCC BY 2.0But by the Classical period (490–323 BCE), Mycenae had become little more than a backwater. Due to this altered political landscape, many classical authors moved Agamemnon’s kingdom from Mycenae to the neighboring Argos, a much more important power during their time.[4] Depending on the source, Agamemnon was thus either king of Mycenae or of Argos.

Whatever eventually happened to his kingdom, the mythical Agamemnon was extremely powerful. According to the Iliad, Agamemnon mustered the largest individual army of any of the Greeks who sailed against Troy, with one hundred ships.[5] He was also the commander-in-chief of the entire expedition.

Military and Royal Attributes

Like many of the other heroes of the Trojan War, Agamemnon had a brilliant suit of armor, described in detail in the Iliad. It included greaves “fitted with silver ankle-pieces”; a breastplate with bands of dark blue, gold, and tin; a sword “whereon gleamed studs of gold, while the scabbard about it was of silver, fitted with golden chains”; a powerful shield with circles of bronze, tin, gleaming white, and dark blue, decorated with a grim, glaring Gorgon; a helmet “with two horns and with bosses four, with horsehair crest;” and, finally, “two mighty spears, tipped with bronze.”[6]

Agamemnon was also said to be in possession of a magnificent scepter fashioned by Hephaestus, the god of the forge.[7]

Skills, Abilities, and Character

Though Agamemnon was usually represented as an impressive fighter—he kills numerous Trojans in the Iliad and other ancient sources[8]—he was also vain, easily discouraged, and overall a subpar general and strategist.

The Curse of Atreus

There was also a dark side to Agamemnon’s power and wealth. His family carried a terrible curse, originally incurred by the cruel and violent feuding between Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, and uncle, Thyestes. This curse—usually known as the “Curse of Atreus”—haunted Agamemnon throughout his life; according to many traditions, it led him to sacrifice his daughter and ultimately die at the hands of his wife and her lover.

Iconography

In ancient art, Agamemnon was usually represented with the typical attributes of royalty: a diadem or his famous scepter. He also tended to have a large beard; as a result, Agamemnon, “lord of men,” looked similar to Zeus, lord of the gods. In painting and sculpture, he appeared in a variety of scenes, most of them related to the Trojan War.[9]

Family

In most traditions, Agamemnon was the son of Atreus and his wife Aerope.[10] Atreus, a son of the hero Pelops (and thus grandson of the infamous Tantalus), competed viciously with his brother Thyestes for the throne of Mycenae. In some traditions, however, Agamemnon was the son not of Atreus but of Atreus’ son Pleisthenes and his wife (whose name was either Aerope, Cleolla, or Eriphyle).[11]

All traditions agreed that Agamemnon’s brother was Menelaus, who later became famous for his rather embarrassing marriage to Helen of Troy. In some traditions, he also had another brother named Pleisthenes[12] and a sister named Anaxibia,[13] Astyoche,[14] or Cydragora.[15]

Agamemnon married Clytemnestra, the daughter of King Tyndareus of Sparta. Together they had one son, Orestes,[16] and several daughters, whose names varied considerably in the ancient sources. According to Homer, our earliest literary source, Agamemnon’s daughters were Chrysothemis, Laodice, and Iphianassa.[17] But most later sources substituted Electra for Laodice[18] and added another daughter, Iphigenia, whom Agamemnon sacrificed so that the gods would allow him to sail to Troy.[19]

This Iphigenia is particularly confusing: in some traditions, Iphigenia was a substitute for Iphianassa;[20] in others, Iphigenia and Iphianassa were two different daughters of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra;[21] in still others, Iphigenia’s name was either Iphimede[22] or Iphigone.[23] To make matters even more confusing, there was one tradition in which Iphigenia was actually the daughter of Clytemnestra’s sister Helen and had merely been adopted by Clytemnestra and Agamemnon.[24]

While at Troy, Agamemnon took several captive women as lovers. These included Chryseis, the daughter of a priest, known for her role in the beginning of the Iliad. By her, Agamemnon was sometimes said to have fathered a son named Chryses.[25]

After the Greeks sacked Troy, Agamemnon carried off the princess Cassandra as his captive. Pausanias reports that they had two sons together, Pelops and Teledamus, both of whom were murdered (together with Agamemnon and Cassandra) by Clytemnestra and Aegisthus.[26]

Some traditions also name Agamemnon as the father of a boy called Halesus, probably a bastard born to one of Agamemnon’s slaves or captives at Troy. This Halesus was an ally of Aeneas and died fighting with him in Italy.[27]

Finally, there was also a tradition that said that Agamemnon had a young male lover named Argynnus who drowned in the river Cephissus in central Greece.[28]

Mythology

Origins and Early Life

Agamemnon grew up in Mycenae, in the court of King Atreus (though ancient sources disagreed on whether Atreus was Agamemnon’s father or grandfather). His childhood was defined by the feuding between Atreus and Atreus’ brother Thyestes. Both men longed for the throne of Mycenae and would stop at nothing to attain their goal.

After a series of monstrous deeds and retaliations (including all forms of robbery, adultery, murder, incest, rape, and even cannibalism), the rivalry between Atreus and Thyestes finally ended when Thyestes murdered Atreus with the help of his son Aegisthus. Thyestes thus became king of Mycenae, while Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus fled into exile.[29]

According to some traditions, Agamemnon and Menelaus were taken in by Tyndareus, the king of Sparta.[30] Eventually, they were able to drive Thyestes out of Mycenae, and Agamemnon became king of the city that had once been his father’s. Some sources say that he expanded his power by conquering neighboring Greek kingdoms.[31]

Agamemnon and Menelaus were soon to become the sons-in-law of Tyndareus, the king who had taken them in when they were exiles. Agamemnon married Tyndareus’ daughter Clytemnestra after murdering her first husband, a man called Tantalus, along with her newborn child.[32] Menelaus, meanwhile, married Tyndareus’ other daughter, the famously beautiful Helen. In most traditions, he also succeeded his father-in-law as king of Sparta.[33]

Agamemnon and Menelaus both became very powerful kings. But the horrific actions of their ancestors—from the villainous Tantalus to their own father Atreus—had brought a curse on them and their family, a curse that would haunt Agamemnon and Menelaus for the rest of their lives.

The Trojan War

The Abduction of Helen and the Oath of Tyndareus

When Helen was abducted (or, according to some sources, seduced) by Paris, a handsome prince from the distant city of Troy, Menelaus immediately turned to Agamemnon for help in getting his wife back.

Helen and Paris by Charles Meynier (19th century).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFortunately for Menelaus, all of Helen’s suitors (and there were many of them) had been forced to swear an oath that they would protect Helen’s marriage and defend the interests of her chosen husband. Because of this oath (the so-called “Oath of Tyndareus”), Menelaus and Agamemnon were able to force the greatest kings and heroes of Greece to join them in sailing to Troy to demand Helen’s return—whether by diplomacy or by force. Agamemnon, the most powerful of the Greek kings, was made commander-in-chief.[34]

Telephus

After assembling the massive Greek force—totaling over one thousand ships, according to the most famous accounts—Agamemnon and Menelaus sailed to Troy. But after a series of misfortunes and delays (including an accidental attack on Troy’s neighbor Mysia and stormy weather), the Greek fleet was scattered and forced to return home.

Eventually, Agamemnon managed to reassemble the Greeks. The army gathered with their fleet at the harbor town of Aulis, in east central Greece, opposite the large island of Euboea. While there, Agamemnon suffered further delays—and personal tragedy.

Agamemnon Musters the Greek Troops at Aulis (from the “Story of Iphigenia”), designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1535–48).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainFirst, Agamemnon nearly lost his infant son to Telephus, the king of Mysia, whose lands the Greeks had accidentally attacked on their first voyage to Troy. In the fighting, Telephus had been wounded by the Greek warrior Achilles; after learning from an oracle that only his “wounder” could heal him, Telephus sailed to Greece, kidnapped Agamemnon’s son Orestes, and threatened to kill the child if the Greeks did not cure him.

In the end, the Greeks did heal Telephus (using shavings from Achilles’ spear—the “wounder” described by the oracle). True to his word, Telephus released Orestes and agreed to help the Greeks reach Troy.[35]

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia

For a long time, however, the Greek fleet could not sail due to unfavorable winds. The prophet Calchas soon revealed the reason: Agamemnon had offended the goddess Artemis (either by killing one of her sacred deer, boasting that he was a better hunter than she, or simply happening to be the future conqueror of Artemis’ beloved Troy). In order to placate her, Agamemnon was ordered to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia (sometimes also called Iphianassa, Iphimede, or Iphigone; see above).

Though reluctant at first, Agamemnon eventually summoned Iphigenia to Aulis and sacrificed her to Artemis. The scene is chillingly described by the Roman poet Lucretius:

She felt the chaplet round her maiden locks

And fillets, fluttering down on either cheek,

And at the altar marked her grieving sire,

The priests beside him who concealed the knife,

And all the folk in tears at sight of her.

With a dumb terror and a sinking knee

She dropped; nor might avail her now that first

'Twas she who gave the king a father's name.

They raised her up, they bore the trembling girl

On to the altar- hither led not now

With solemn rites and hymeneal choir,

But sinless woman, sinfully foredone,

A parent felled her on her bridal day,

Making his child a sacrificial beast

To give the ships auspicious winds for Troy.[36]

The sacrifice thus completed, Artemis gave the Greeks a favorable wind, and they sailed for Troy once again.[37] But in one tradition (perhaps even the more common tradition), Artemis took pity on the girl and rescued her by replacing her with a deer (or a bull) as she stepped onto the altar. The Greeks killed the deer, and Iphigenia was spirited away to serve Artemis as a priestess.[38]

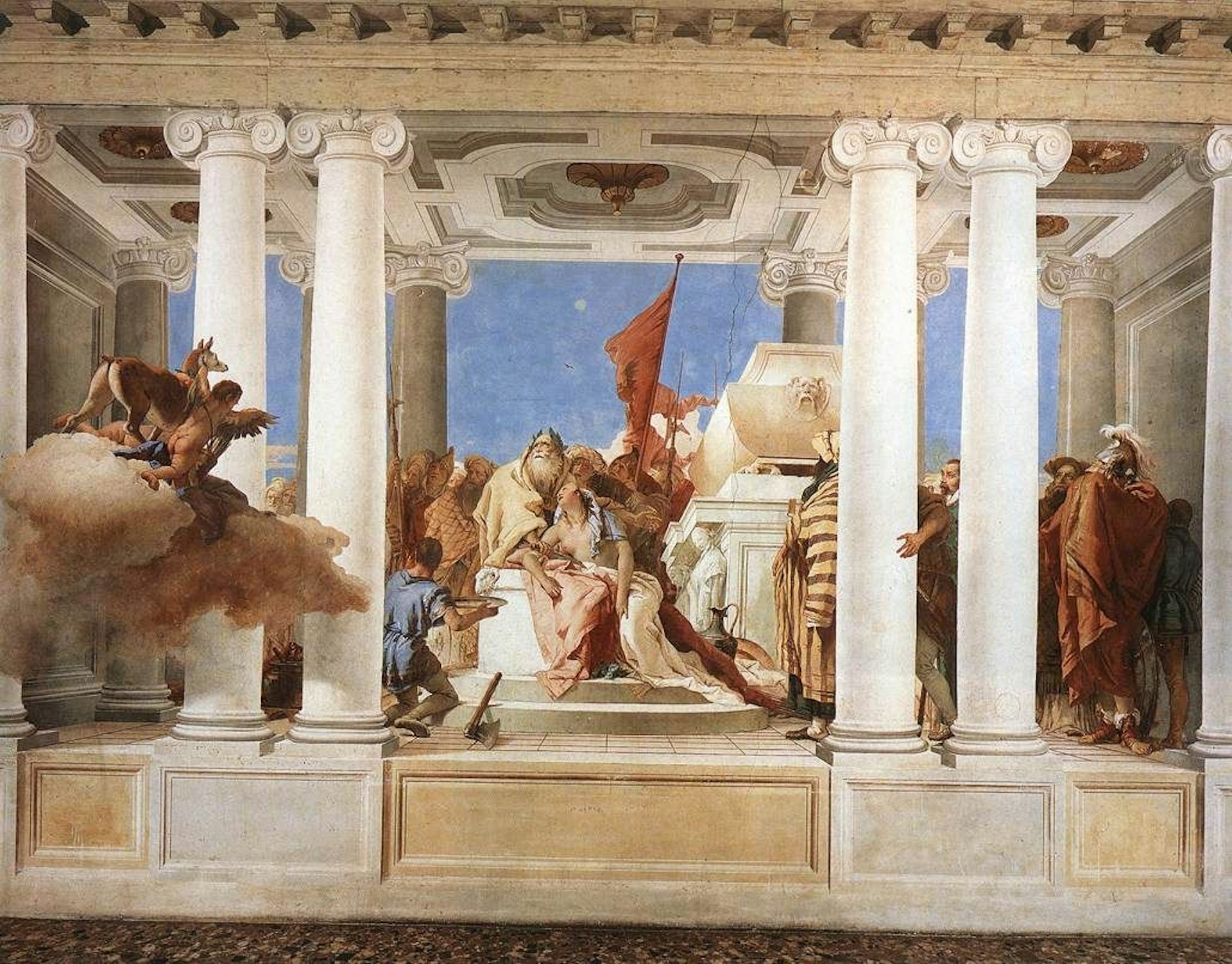

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1757). Villa Valmarana, Bolzano Vicentino, Italy.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAgamemnon in the Iliad

Agamemnon is one of the main characters of Homer’s Iliad, an epic poem set during the ninth year of the Trojan War. The first book of the Iliad describes the events that led to a terrible quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles, the greatest warrior in the Greek army.

Agamemnon had captured a girl named Chryseis during a raid. Chryseis’ father, Chryses, an important priest of Apollo, offered Agamemnon a large ransom for his daughter. But the arrogant Agamemnon refused and rudely threw Chryses out of the Greek camp. Furious, Chryses prayed to Apollo to punish the Greeks for Agamemnon’s behavior. Apollo promptly responded by unleashing a terrible plague on the Greeks.[39]

The prophet Calchas soon revealed Agamemnon’s role in the Greeks’ suffering. When Achilles heard this, he publicly demanded that Agamemnon release Chryseis, as her father had asked. Agamemnon agreed, but in turn he demanded that Achilles give up his own slave girl, Briseis, to compensate for Agamemnon’s loss. After flying into a rage and nearly killing Agamemnon, Achilles agreed to let him have his slave girl—but he refused to fight for him anymore.[40]

The Anger of Achilles by Jacques-Louis David (1819). Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX.

Google Arts and CulturePublic DomainWith their best warrior out of the fray and the war already in its ninth year, the Greeks suffered a setback in morale. To make matters worse, Achilles’ mother Thetis had also convinced Zeus to punish Agamemnon and the Greeks for dishonoring her son. Thus, in the days that followed Agamemnon’s unfair seizure of Briseis, Zeus caused the Greeks to suffer heavy losses at the hands of the Trojans.[41]

Eventually, Agamemnon realized that the Greeks would continue to be pushed back by the Trojans (led by the brave prince Hector) as long as Achilles refused to fight. Thus, he sent three of Achilles’ friends—Odysseus, Ajax the Greater, and Phoenix—to apologize to Achilles on his behalf. But though Agamemnon offered Achilles many gifts in exchange for returning to the fight (including, of course, the restoration of his slave girl Briseis), Achilles could not let go of his wounded pride. He refused Agamemnon’s attempt to make amends.[42]

In the days that followed, the battle continued to rage. Despite the valiant efforts of several Greek heroes—including Agamemnon, who has an impressive “day of glory” (sometimes called an aristeia) in Book 11 of the Iliad—the Trojans eventually pushed the Greeks back to their camp. Hector even managed to break through the Greeks’ defenses and started to burn their ships.[43]

Finally, as matters were looking particularly grim (and with Agamemnon increasingly considering a retreat from Troy), Achilles’ close friend Patroclus begged Achilles to help the Greeks. Achilles refused but allowed Patroclus to borrow his famous armor and lead his warriors, the Myrmidons, against Hector and the Trojans. As soon as the Trojans saw what looked like Achilles returning to battle, they immediately fled. But Patroclus pressed his luck too far and was ultimately killed by Hector.[44]

When Achilles found out that his best friend was dead, he forgot his quarrel with Agamemnon; now he wanted only to kill Hector. The next day, he accepted Agamemnon’s gifts and set out against the Trojans. He fought and killed Hector in single combat, depriving Troy of its best fighter and giving the Greeks the upper hand. The Iliad ends with Hector’s funeral in Troy.[45]

The Fall of Troy

After Hector fell, the Trojan War dragged on a bit longer, with both sides suffering important losses (e.g., Penthesilea, Memnon, and Paris on the Trojan side, and Achilles and Ajax the Greater on the Greek side).

Eventually, the clever Greek king Odysseus came up with a plan to get past Troy’s impregnable walls and win the war: the Trojan Horse, a hollow wooden horse in which a handful of Greek heroes hid while the rest of the army pretended to retreat. After the Trojans took the horse into their city, the heroes inside stole out under cover of night and opened the gates to the rest of the army. In this way, the Greeks finally conquered Troy after ten years of fighting.[46]

Battle in the Palace of Priam by Jean Mignon (1535–1555).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAfter Troy had been burned and sacked, the Greeks divided the spoils and prisoners among themselves. Agamemnon claimed Priam’s daughter, the prophetess Cassandra, as his prize.[47]

But in one tradition, Agamemnon and Menelaus disagreed on what to do after their victory. Menelaus wanted to sail home immediately, while Agamemnon wanted to stay and offer sacrifices to the gods. In the end, the fleet split up: Menelaus and several others left without sacrificing (and were punished for their impiety with a storm sent by the gods), while Agamemnon stayed behind. Because of this, the Greek heroes did not all arrive home at the same time.[48]

Death

Laden with spoils and glory, Agamemnon sailed back home to Mycenae. But in his absence, Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, had taken Aegisthus (Agamemnon’s cousin and oldest enemy) as her lover. Together they plotted to murder Agamemnon.

When Agamemnon returned home, Clytemnestra gave him a lavish welcome. She invited him to come with her to the palace. Despite the warnings of his captive Cassandra—who had been given the ability to see the future by Apollo—Agamemnon walked into his wife’s trap.

In the earliest attested version, Agamemnon was ambushed by Aegisthus at a feast given in his honor and killed, along with many of his men and Cassandra.[49] In Homer’s Odyssey, when Agamemnon meets Odysseus in the Underworld, he recalls that he was butchered “even as one slays an ox at the stall.”[50]

In other versions, it was Clytemnestra (either alone or with Aegisthus’ help) who did the killing after trapping Agamemnon in a net or a robe while he was in his bath. Clytemnestra then killed Cassandra too.[51]

Clytemnestra Hesitates before Killing the Sleeping Agamemnon by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1817). Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAftermath of the Death of Agamemnon

The cycle of violence inspired by the famous “Curse of Atreus” did not end with Agamemnon’s murder. Eventually, Agamemnon’s son Orestes would go on to avenge his father by murdering both Aegisthus and Clytemnestra. In this he was helped especially by his sister Electra. After the murder, Orestes was pursued by the Erinyes (also known as the Furies) until he was eventually purified by Apollo.[52]

Surprisingly, the myths about Agamemnon do not end with his death: he makes two post-mortem appearances in Homer’s Odyssey. In one episode, he meets Odysseus during the hero’s journey through the Underworld.[53] Agamemnon explains how he was murdered as soon as he came home and warns Odysseus never to trust women, not even his own wife Penelope:

And another thing will I tell thee, and do thou lay it to heart: in secret and not openly do thou bring thy ship to the shore of thy dear native land; for no longer is there faith in women.[54]

In Agamemnon’s second appearance in the Odyssey, he greets Penelope’s suitors after they are killed by Odysseus and descend to the Underworld.[55]

Worship

Agamemnon received hero worship in many parts of the Greek world, and was sometimes even equated with Zeus.[56] There were at least two sites that claimed to house and pay heroic honors to Agamemnon’s remains: Agamemnon’s traditional kingdom of Mycenae[57] and the Laconian town of Amyclae, just southeast of Sparta.[58] At both sites, Agamemnon was said to have been buried together with the Trojan Cassandra, who died with him.

Agamemnon was worshipped at other sites as well. These included the region of Laconia;[59] Chaeronea in central Greece, which claimed to be in possession of Agamemnon’s scepter;[60] Clazomenae on the coast of Anatolia;[61] and Tarentum in southern Italy.[62] There was also an important statue of Agamemnon at Olympia, the site of the Olympic Games.

Pop Culture

Agamemnon has retained a significant presence in modern pop culture, especially in adaptations of the Trojan War myth. He is an important character in novels such as Barry Unsworth’s The Songs of the Kings (2002), David Gemmell’s Troy trilogy (2005–2007), and Margaret Miller’s The Song of Achilles (2011); in plays such as Eugene O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra (1931); in poems such as Denton Jacques Snider’s Agamemnon’s Daughter: An Epopee (1885); and in graphic novels such as Eric Shanower’s Age of Bronze series (1998–).

Agamemnon has also appeared in film and television, with various actors taking on the role. In film, these include Robert Douglas in Helen of Troy (1956), Nerio Bernardi in The Trojan Horse (1961), Mario Petri in The Fury of Achilles (1962), Sean Connery in Time Bandits (1981), and Brian Cox in Troy (2004). In television, Agamemnon has been portrayed by Yorgo Voyagis in The Odyssey (1997), Rufus Sewell in Helen of Troy (2003), and Johnny Harris in Troy: Fall of a City (2018).

Finally, Agamemnon has been featured in other media, such as the video game Total War Saga: Troy (2020).

Most modern adaptations of Agamemnon represent the character unfavorably. He is seen as a cruel and greedy king who will stop at nothing to achieve his goals, even if that means sacrificing his own daughter.