Persephone

The Spring Witch by George Wilson (ca. 1880).

Delaware Art MuseumPublic DomainOverview

Persephone, often known simply as Kore (“Maiden”), was a daughter of Zeus and Demeter. Her mythology tells of how she was abducted by her uncle Hades one day while picking flowers. Demeter, distraught, wandered the entire world in search of her daughter.

When Demeter at last located Persephone in the Underworld, she demanded that her daughter be returned. But Hades had tricked Persephone into eating something—a handful of pomegranate seeds—while she was in the Underworld. Thus, although Persephone was allowed to spend part of the year on Olympus with her mother, she was forced to spend the other part of the year in the Underworld as Hades’ bride.

As the wife of Hades, Persephone was the queen of the Underworld. She was also associated with spring, girlhood, and marriage. Persephone was often worshipped alongside her mother, Demeter—for example, in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Etymology

Ancient authors sometimes sought creative etymologies for the name “Persephone” (Greek Περσεφόνη, translit. Persephonē). Plato, for example, interpreted the name as “she who touches things that are in motion” (epaphē tou pheromenou), a reference to Persephone’s wisdom (to touch things that are in motion implies an understanding of the cosmos, which is constantly in motion).[1]

Other ancient etymologies connected Persephone’s name with aphenos (“wealth”), phonos (“death”), and phōs (“light”). But these are folk etymologies that lack credibility.

Nowadays, Persephone’s name is often thought to have Indo-European origins. Robert Beekes and others have connected it to two Indo-European roots: *perso- (“sheaf of corn”) and *-gʷn-t-ih₂ (“hit, strike”). This would indicate that Persephone’s name means something like “female corn thresher.”[2]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Persephone Περσεφόνη (translit. Persephonē) Phonetic

IPA

[per-SEF-uh-nee] /pərˈsɛf ə ni/

Alternate Names

The name Kore (Korē, “Maiden”) was commonly used as an alternative to “Persephone” and highlighted the goddess’s role as the daughter of Demeter, goddess of agriculture. Another alternate name, Despoina (“Mistress”), focused on Persephone’s role as the wife of Hades and queen of the Underworld.

There were several alternate forms of the name “Persephone” itself, including Persophatta or Persephatta (which may have been the original form of the name), Persephoneiē (the Homeric form), Pherrephatta, and Phersephonē.

Persephone’s Roman counterpart was called Proserpina or Proserpine.

Titles and Epithets

Persephone was known by numerous cult titles, including Sōteira (“Savior”) and Brimō (“Angry”). She also had a handful of epithets. These included epainē (“awful”), which stressed Persephone’s role as queen of the Underworld, as well as agauē (“venerable”), hagnē (“holy”), and arrētos (“she who must not be named”).

Attributes

There were two sides to Persephone. On the one hand, she was Persephone, wife of Hades and goddess of the Underworld, and thus a chthonic figure closely associated with the inevitability of death. On the other hand, she was Kore, the maiden daughter of the agricultural goddess Demeter, an alternate guise that brought her into the sphere of agriculture and fertility. In her ritual and mythology, Persephone/Kore was also regarded as a goddess of all aspects of womanhood and female initiation, including girlhood, marriage, and childbearing.

True to her double nature, Persephone was imagined as having two homes: one on Olympus with her mother, Demeter, and the other in the Underworld with her husband, Hades. According to Homer, she also possessed sacred groves on the western edge of the world, near the entrance to the Underworld.[3]

In her iconography, Persephone was represented as a young woman, modestly clad in a robe and wearing either a diadem or a cylindrical crown called a polos on her head.

Persephone was characterized by several attributes and symbols, most notably torches, stalks of grain or ears of corn, and scepters. More rarely, she was associated with pomegranates or poppies. Other attributes, such as the rooster, were more localized and tied to the iconography of specific cults.

Pinax (sculpted votive tablet) from the temple of Persephone in Epizephyrian Locris showing Persephone, holding a cock and grain, sitting beside her husband Hades. National Archaeological Museum, Reggio di Calabria, Italy.

AlMareCC BY-SA 4.0Several scenes from Persephone’s mythology—especially her abduction by Hades—were popular among ancient artists.[4]

Family

In the standard tradition, Persephone was the daughter of Zeus, the king of the gods, and his sister Demeter, the goddess of agriculture.[5] But there were a handful of rival traditions surrounding Persephone’s parentage, including one in which she was the daughter of Zeus and Styx, an Oceanid who gave her name to one of the rivers of the Underworld.[6] The Orphic version of Persephone, on the other hand, was a daughter of Zeus and Rhea,[7] while an Arcadian version of Persephone called Despoina was the daughter of Demeter and Poseidon.[8]

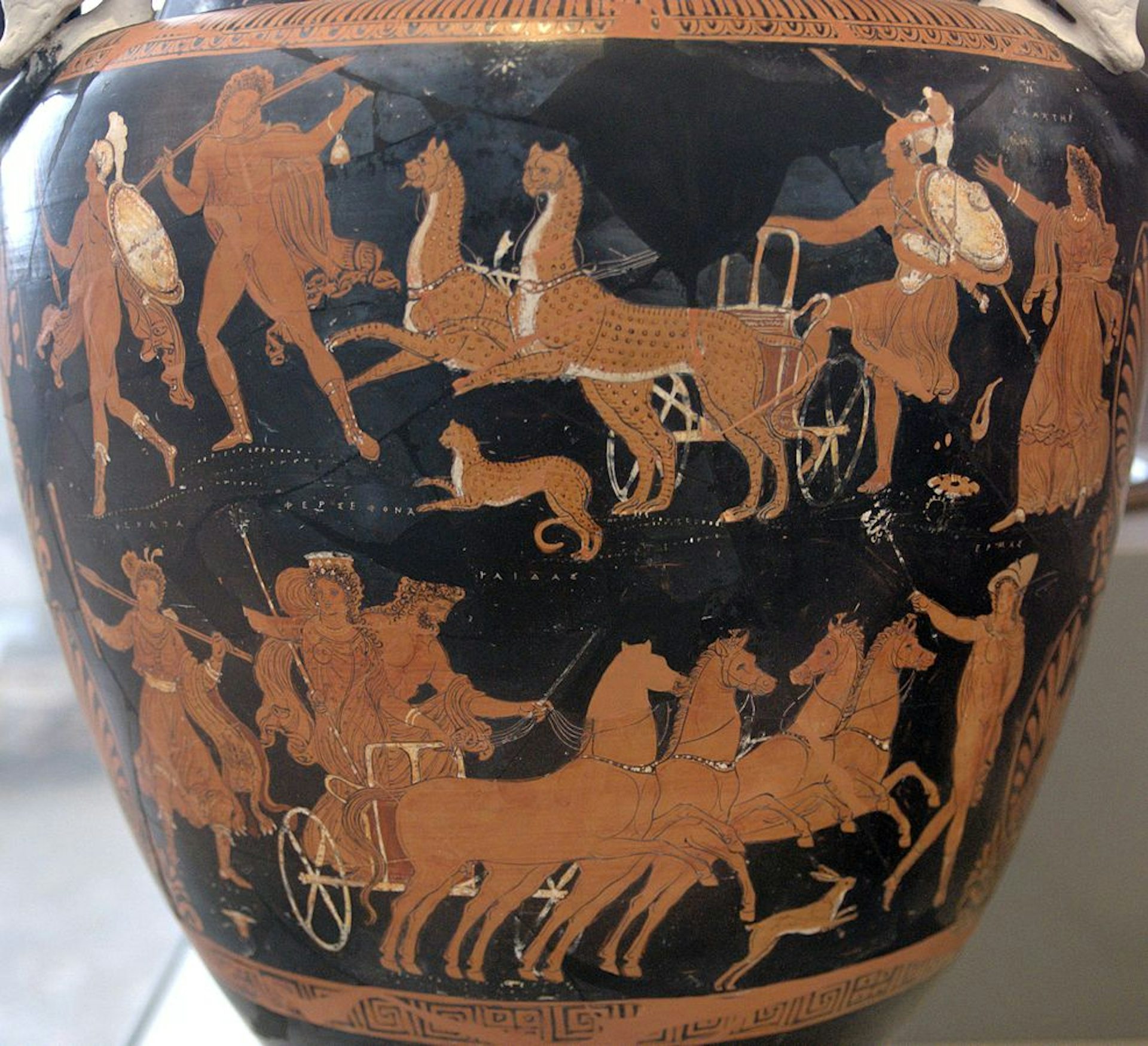

The so-called “Persephone Krater,” an Apulian red-figure volute-krater by the Circle of the Darius Painter (ca. 340 BCE). Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany.

Bibi St. PaulPublic DomainPersephone was usually regarded as the only child born to Zeus and Demeter, but both gods had children with other consorts. Thus, Persephone’s half-siblings included Demeter’s other children (Arion, Corybas, and Plutus) as well as the numerous children of the promiscuous Zeus (including Apollo, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Heracles, Perseus—and many, many others).

Family Tree

Mythology

Abduction by Hades

Persephone was the daughter of Demeter and Zeus. The most detailed account of her myth comes from the second Homeric Hymn, also known as the Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

This poem describes how Persephone was picking flowers in a meadow when she was abducted—with Zeus’ permission[14]—by Hades, the god of the Underworld and the brother of Demeter and Zeus (and thus Persephone’s uncle).[15] Later sources added that it was Aphrodite and Eros who caused Hades to fall in love with Persephone in the first place.[16]

The Rape of Proserpine by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1621/1622). Borghese Gallery, Rome, Italy.

AlvesgasparCC BY-SA 4.0The Homeric Hymn then tells of how Demeter, realizing her daughter was missing, began a desperate search. After wandering the entire earth, Demeter finally learned the truth from Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft, who had happened to hear Persephone cry out before she disappeared.

Though Hecate did not know where Persephone had been taken, she told Demeter to seek information from Helios, the charioteer of the sun, who was the only witness to the crime. Sure enough, Helios was able to tell Demeter how Hades had abducted her daughter.[17]

Upon discovering that Hades had Persephone—and that Zeus himself had helped him kidnap her—Demeter was justifiably furious:

But grief yet more terrible and savage came into the heart of Demeter, and thereafter she was so angered with the dark-clouded Son of Cronos that she avoided the gathering of the gods and high Olympus, and went to the towns and rich fields of men, disfiguring her form a long while.[18]

Eventually, Demeter’s wanderings brought her to Eleusis, a town in the region of Attica, just northwest of Athens. Demeter arrived at the palace disguised as an old woman, where she was treated kindly by Queen Metaneira and King Celeus. In return, she nursed their sick child, known as Demophon in most versions of the myth,[19] and tried to make him immortal.

When Demeter’s efforts to impart immortality failed (the boy’s mother, Metaneira, inadvertently interrupted the process when she saw Demeter holding the child in a fire), Demeter commanded the Eleusinians to build her a temple. She then abandoned her functions as the goddess of agriculture, causing grain to stop growing and nearly starving humanity. Demeter’s terrible rage was ended only through the intervention of Zeus, who sent the messenger god Hermes to persuade Hades to return Persephone to Demeter.

Hades told Hermes he would release Persephone—as long as she had not tasted food while in the Underworld. He then tricked Persephone into eating a handful of pomegranate seeds. Because of this, Persephone could not leave Hades for good. In the end, a compromise was reached: Persephone would spend part of the year in the Underworld as Hades’ wife and the other part on Olympus with her mother, Demeter.[20]

Persephone in the Underworld

Persephone was the queen of the Underworld and so ruled over all mortals who had died. Though dreaded, she did sometimes listen to and grant requests. For example, she allowed the prophet Tiresias to keep his reasoning and prophetic abilities even in death.[21]

Persephone also featured in the myths of a handful of heroes and mortals who descended to and returned from the Underworld. According to one source, she was the one who allowed Orpheus to bring his dead wife Eurydice back from the Underworld, provided he did not look back while leading her up (a condition that Orpheus failed to meet).[22]

In another story, Theseus agreed to help Pirithous abduct Persephone from the Underworld, but they were caught and held prisoner. In some versions, Persephone eventually allowed Heracles to bring Theseus and Pirithous back with him when he came to the Underworld to fetch Cerberus (as part of his final labor).[23]

Persephone also featured in some versions of the myth of Alcestis. When Alcestis’ husband Admetus was told that he could put off his death if he found somebody willing to die in his place, Alcestis bravely volunteered. According to some authors, Persephone was so moved by this deed that she allowed Alcetis to return to the land of the living (in the more familiar version, though, Alcestis was brought back by Heracles).[24]

At least one person tried to take advantage of Persephone’s amenable nature. When Sisyphus wanted to escape death, he came up with a clever trick. He told his wife not to bury him; then, when he arrived in the Underworld, he convinced Persephone (though in some versions it was Hades) to let him return to the world of the living to punish his wife for neglecting his funeral.[25]

Lovers and Rivals in Love

The fact that Persephone was married did not prevent her from being imagined as a virginal maiden. There were, however, a handful of myths that challenged this persona.

According to some sources, Persephone vied with Aphrodite for the love of Adonis, an astonishingly handsome mortal man. Eventually, Zeus determined that Adonis would spend part of the year with Aphrodite and part of the year with Persephone.[26]

Terracotta loutrophoros (ceremonial water jug) attributed to the Darius Painter (ca. 340–330 BCE). The upper register of the body shows Zeus between Persephone and Aphrodite regarding Adonis.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn another myth, Hades took a nymph named Minthe as his lover. When Persephone found out, she jealously trampled Minthe and turned her into a plant: garden mint.[27]

Orphic Mythology

The Orphics, an ancient Greek religious community that subscribed to distinctive beliefs and practices (called “Orphism,” “Orphic religion,” or the “Orphic Mysteries”), had their own unique mythology of Persephone.

According to several strands of Orphism, Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and his mother, the Titan Rhea (rather than Demeter). She was conceived after Zeus transformed himself into a snake to have sex with Rhea. When Persephone was born, she had a monstrous form, with numerous eyes, an animal’s head, and horns. Terrified, Rhea refused to nurse the child and fled. But Zeus transformed into a snake again and had sex with Persephone, whereupon she conceived the god often called Zagreus or Dionysus Zagreus.[28]

Worship

Temples

Persephone had temples throughout the Greek world, many of them shared with Demeter. The most notable of these was the Temple of Demeter in Eleusis, a huge, ancient temple likely built during the seventh century BCE. The famous “Eleusinian Mysteries,” religious rites honoring Demeter and Persephone/Kore, were performed there.

A view of the excavation of Eleusis, Greece. This is the site of the annual Eleusinian Mysteries and an early temple to Demeter and Persephone, built around the 7th century BCE.

Marcus CyronsCC BY-SA 2.0Persephone shared many other temples with Demeter, though she also had several temples of her own; the one at Epizephyrian Locris (a Greek colony in southern Italy) is an important example.[29] At other sites, including Teithras in Attica,[30] Acrae in Sicily,[31] and the island of Thasos,[32] Persephone had a separate sanctuary called a Koreion.

Elsewhere, such as Cyzicus,[33] Erythrae,[34] Sparta,[35] Megalopolis in Arcadia,[36] and the Athenian deme of Corydallus,[37] Persephone was worshipped with the cult title Soteira, meaning “Savior.”

Festivals and Rituals

Just as Persephone shared many of her temples with Demeter, she also shared many of her festivals with her.

The most important festival of Persephone and Demeter, the Thesmophoria, was celebrated by married women throughout the ancient Greek world. In Athens, the Thesmophoria lasted three days and involved several rituals, including one in which the rotten remains of a slaughtered pig were dug up and placed on the altars of the goddesses.[38] The Thesmophoria was also celebrated in other parts of Greece, such as the region of Boeotia.[39]

Many of the festivals of Persephone and Demeter were related to the myth of Persephone’s abduction. At Eleusis, worshippers reenacted Demeter’s search for Persephone at night by torchlight. When Persephone was “found,” the ritual ended with celebration, torch throwing, and probably the sounding of a gong.[40] At Megara, similarly, worshippers reenacted Persephone’s abduction by a sacred rock called Anaklēthris, where Demeter was believed to have “called back” (anekalesen in Greek) Persephone when she passed by it during her search.[41]

In Sicily, sometimes said to have been the island from which Hades had abducted the goddess, Persephone was honored in a number of different festivals and rituals. The Korēs Katagōgē (“Descent of Kore”), for example, commemorated Hades taking Persephone (Kore) down to the Underworld.[42] Every year in the Sicilian city of Syracuse, Persephone was honored with the sacrifices of smaller animals and the public drowning of bulls.[43]

Another festival, called the Chthonia, was celebrated annually at Hermione, a city in the Argolid. It honored Demeter in her connection with Persephone, the queen of the Underworld. One part of the festival involved four old women who sacrificed four heifers with sickles.[44]

Other festivals celebrated Persephone in connection with the institution of marriage (rather than with Demeter and agriculture). This seems to have been how Persephone was honored at her temple in Epizephyrian Locris. In some Sicilian cities[45] and in the Locrian colony of Hipponion,[46] there were festivals celebrating Persephone’s wedding.

In Cyzicus, where Persephone was worshipped under the title Soteira, her festival was called either the Soteria,[47] the Pherephattia,[48] or the Koreia.[49] A festival called the Koreia appears to have also been celebrated in Arcadia[50] and Syracuse[51] (though the Syracusean Koreia was likely simply the equivalent of the Thesmophoria).

Persephone, both individually and together with other gods, was also honored through festival and ritual at numerous other sites, including Mantinea, Argos, Patrae, Smyrna, and Acharaca.

Other Worship: Orphism and Curse Tablets

The Orphics, who called Persephone either Despoina[52] or the “Chthonian Queen,”[53] worshipped her primarily in connection with the Underworld. They also associated her with salvation: it was believed that she would grant a blissful afterlife to those who had been properly purified.

Persephone was often invoked on curse tablets under her Underworld title Despoina. Curse tablets were engraved texts that called upon a god, usually a “chthonian” god associated with the Underworld (such as Hecate, Hermes, or Gaia), to punish or harm an enemy, who would generally be named in the text.

Pop Culture

Persephone has continued to captivate the modern imagination as the virginal yet terrifying queen of the Underworld. She has appeared in a handful of modern adaptations of Greek mythology, including Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians franchise, the 1990s TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, and even the video game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey.

Together with Demeter, Persephone is also depicted on the Great Seal of North Carolina, where she is shown in a pastoral setting with the sea in the background.