Pan

Silhouetted study of Pan in a Niche by an unknown Italian artist (18th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Rustic Pan was the Greek god of shepherds, goatherds, and their animals and pastures. He himself was part-animal and was most often imagined with the horns, hind legs, and tail of a goat. Originally an Arcadian god, Pan’s fame had already spread by the beginning of the fifth century BCE, and he was soon worshipped across the Greek and Roman world.

In literature and art, Pan was commonly represented as a carefree and easygoing god (as long as his midday siestas were not disturbed). He spent his days hunting, dancing, or playing his beloved pipes. Pan was known above all for his insatiable lust and for pursuing beautiful nymphs throughout the woodlands and mountains—though these chases tended to end in frustration, with the objects of his desires fleeing him or changing their shape.

Etymology

Today, the name “Pan” (Greek Πάν, translit. Pán; sometimes spelled Πᾶν/Pân or Πάων/Páōn) is usually thought to have come from an early Greek word meaning “shepherd” or “herdsman,” derived from the same Indo-European root as the Latin words pastor (“shepherd”) and pascor (“to graze”).

In antiquity, however, there were different folk etymologies that were used to explain Pan’s name. These usually derived the name incorrectly from the Greek word πᾶς (pâs), meaning “all.” In one source, Pan was given his name because his amusing appearance delighted “all” the gods of Olympus;[1] likewise, some philosophers attributed his name to the fact that Pan was a god of “all things.”[2]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Pan Πάν (Pán) Phonetic

IPA

[pan] /pæn/

Titles and Epithets

Pan’s cult titles and epithets tended to refer to his preferred pastimes. Some of these titles included ἀγρεύς (agreús, “he of the hunt”), νόμιος (nómios, “he of the pastures”), and ἀγρέτης (agrétēs, “he of the fields”).

Pan’s Roman counterpart was the rustic, part-goat god Faunus.

Attributes

Functions

Pan was a nature deity who seems to have originally been worshipped in Arcadia, a pastoral region of the northern Peloponnese. However, he was soon adopted throughout the Greek and Roman world.

Pan was above all a god of goatherds and shepherds, as well as their domestic animals and pastures. But he was also associated with other aspects of the pastoral sphere, from beekeeping to hunting to fishing; by extension, he could also be counted as a fertility god. More rarely, Pan was thought to possess oracular powers, and in one tradition it was he who taught Apollo the art of prophecy.[3]

Appearance and Abilities

Pan was a male deity with goat features. He was generally represented with the hind legs, tail, horns, and ears of a goat, as well as a rather goatish face, complete with scraggly beard and a muzzle or snout.[4] There were, of course, variations on this image; some made Pan more goatish by giving him a goat head,[5] while others made him more human by giving him the face of a young man.[6]

Pan’s companions were other nature deities and creatures, especially nymphs, satyrs, and the god Dionysus. Pan passed his days in pastoral activities, including hunting, music, and dancing:

He has every snowy crest and the mountain peaks and rocky crests for his domain; hither and thither he goes through the close thickets, now lured by soft streams, and now he presses on amongst towering crags and climbs up to the highest peak that overlooks the flocks. Often he courses through the glistening high mountains, and often on the shouldered hills he speeds along slaying wild beasts, this keen-eyed god. Only at evening, as he returns from the chase, he sounds his note, playing sweet and low on his pipes of reed…[7]

Pan’s attributes corresponded to his favorite activities. The most important of these attributes was undoubtedly the syrinx, an instrument made of reed pipes of different lengths which Pan himself was said to have invented.[8]

Pan was notorious for taking his midday siesta very seriously; those who disturbed his rest brought the god’s terrible wrath upon their heads.[9] Indeed, in his rage Pan was capable of inducing a “panic fear” (panikòn deîma), an irrational and groundless terror that could suddenly befall entire groups of people. Pan was said to have inspired this panic on several occasions when foreign armies invaded Greece—for instance, during the first Persian invasion of 490 BCE or when the Galatians attacked Delphi in 279 BCE.[10]

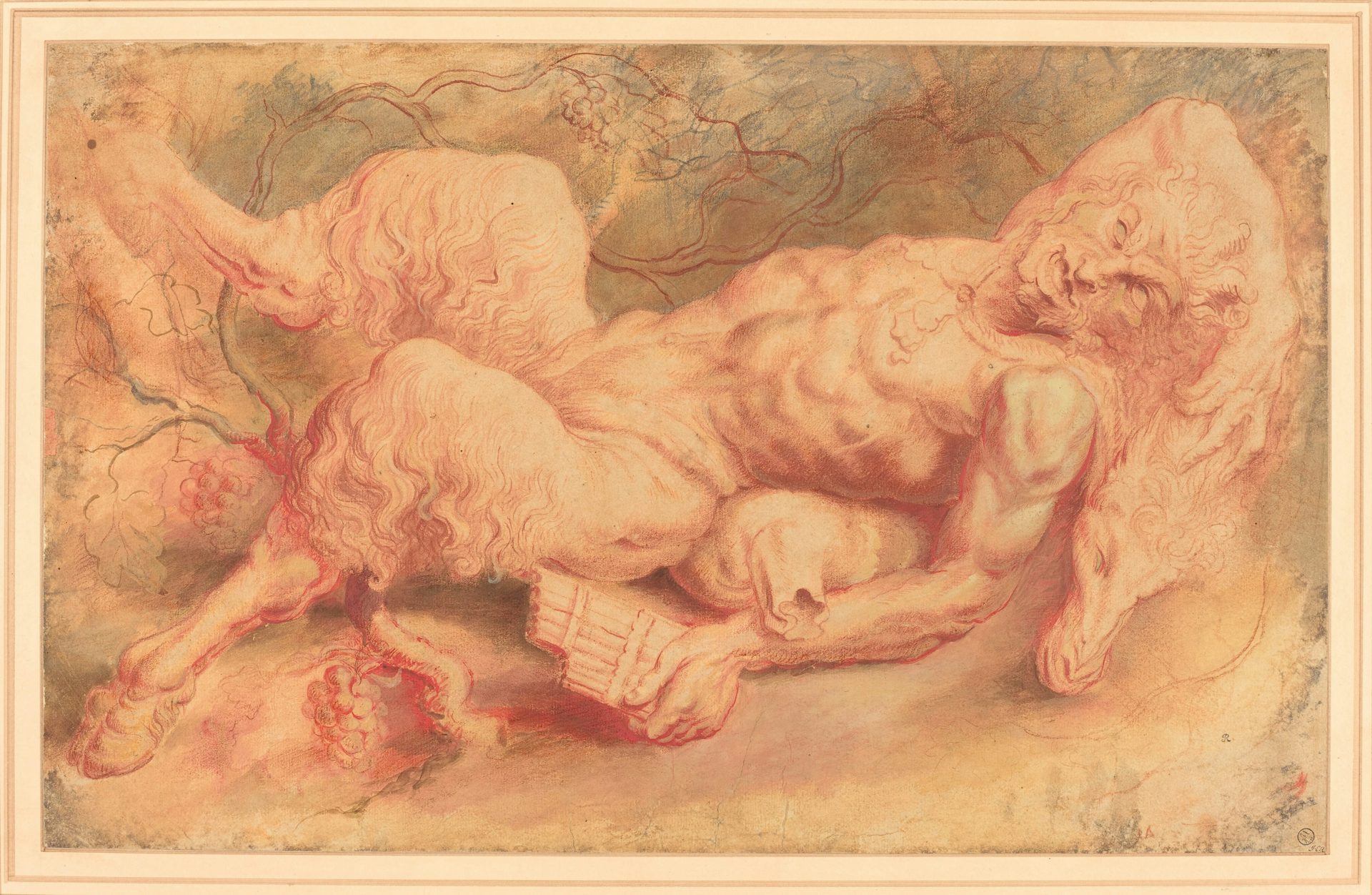

Pan Reclining by Peter Paul Rubens (possibly ca. 1610)

National Gallery of Art (US)Public DomainPan could also possess individuals and force them to commit acts of savage violence. The ancients referred to this terrible ability as “panolepsy.”[11]

Constellation

Pan was sometimes connected with the constellation Capricorn, which the Greeks knew as Aegocerus (meaning “goat-horned”). He was given this honor, at least in one tradition, because his advice had saved the gods when they were attacked by the monster Typhoeus. Pan suggested the gods disguise themselves as animals and hide from their terrible enemy (he followed his own advice by turning into a goat). After Zeus defeated Typhoeus, he rewarded Pan for his sage counsel by putting him in the stars as Capricorn, the celestial goat.[12]

Pan and the Pans

Pan was sometimes multiplied into a mob of “pans,” goat-featured woodland creatures much like him; some sources even spoke of female pans.[13] Sometimes these creatures were the offspring of Pan,[14] while other times they were the offspring of Hermes, who in certain traditions was also the father of Pan.[15] These pans, like Pan himself, were often represented as members of Dionysus’ entourage.[16]

One of the pans, Aegipan, was more notable than the others; in fact, he may have been identical with Pan himself. Some of the myths involving Aegipan were also told of Pan, and both creatures were connected with the constellation Capricorn.[17]

Iconography

Pan’s image evolved throughout the history of ancient art. It seems that in his earliest representations he was all goat, but he soon began to acquire human characteristics. By the end of the fifth century BCE, Pan’s iconography was fairly well established: the god was usually represented as a male with a human torso, but with the hind legs, horns, ears, and tail of a goat. Though he sometimes sported a goat’s head, his face was usually a hodgepodge of features, combining human attributes with a scraggly goat beard and muzzle.

Of course, there were variations on this basic form. Sometimes Pan was more human, with only discreet horns and a short tail signifying his rustic nature. In other depictions, he had a mostly human body but a goat’s head.

Pan was typically shown nude, often with a large erect penis (similar to satyrs and silens). He was invariably depicted partaking in his favorite activities: dancing, playing music, and hunting. He was also frequently shown consorting with other rustic or nature deities, especially Dionysus, but sometimes Aphrodite or Eros as well.

Marble statue of Pan, Aphrodite, and Eros (ca. 100 BCE). Aphrodite threatens Pan with a sandal as he makes advances towards her, while a winged Eros plays with Pan’s horns.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / Helen SimonssonCC BY-SA 2.0Pan’s most recognizable attribute, in art as in literature, was the syrinx, the reed pipe he was said to have invented. However, artists sometimes showed him playing other instruments, too, such as the aulos (a pipe or flute used in more formal occasions), the lyre, or the cithara. Other attributes in Pan’s iconography included the lagobolon (a weapon used for hare hunting), as well as a torch of thyrsus (an ivy-covered wand), typically featured in scenes with both Pan and Dionysus.

Pan was a popular subject in ancient Greek vase painting, but he was also featured in sculpture, painting, relief, and on small votive offerings (clay figurines, lamps, etc.). As a kind of national god of Arcadia, Pan appeared on coins minted in the region from an early date—for instance, on fourth-century BCE coins of the Arcadian League. His iconography eventually spread west to southern Italy, Etruria, and Rome.[18]

Family

There are some fourteen known versions of Pan’s parentage, many of them reflecting local traditions about the god:[19]

Pan was the child of Zeus and the Arcadian princess (or nymph) Callisto (and thus the brother of Arcas).[20]

Pan was the child of Zeus and a nymph called Oeneis.[21]

Pan was the child of Zeus and Hybris, the personification of insolence.[22]

Pan was the child of Aether (the Upper Air or Atmosphere) and a nymph named Oenoe (or Oeneis).[23]

Pan was the child of Hermes and a daughter of the hero Dryops.[24]

Pan was the child of Hermes and Penelope, the wife of Odysseus.[25]

Pan was the child of Hermes and the nymph Orsinoe.[26]

Pan was the child of Apollo and Penelope.[27]

Pan was the child of Penelope and all 108 of her suitors.[28]

Pan was the child of Odysseus and Penelope.[29]

Pan was the child of Cronus, the most powerful of the Titans.[30]

Pan was the child of Uranus and Gaia (and thus the brother of the Titans, Cyclopes, and Hecatoncheires).[31]

Pan was the child of a shepherd named Crathis and one of his goats.[32]

Pan was the child of Arcas, an early ruler of Arcadia.[33]

Stories about Pan’s consorts (or would-be consorts) are also numerous and diverse. More often than not, the objects of Pan’s desires ended up escaping him. But Pan was not always frustrated in his amorous pursuits, as attested by the list of children he had with various women, usually nymphs. One source mentions in passing that Pan had a wife named Aex (“goat”),[34] and in one tradition Pan was a lover of Selene, the goddess of the moon.[35]

Attic red-figure kylix showing Selene, said to have been one of Pan’s lovers, riding the chariot of the moon. Attributed to the Byrgos Painter, ca. 500–450 BCE.

Altes Museum, Berlin / Miguel Hermoso CuestaCC BY-SA 4.0From these scattered sources, we can compile a formidable list of children fathered by Pan. By Eupheme (the nurse of the Muses), Pan was the father of Crotus, who was sometimes said to have been put in the stars as the constellation Sagittarius after his death.[36] By the nymph Echo, he was the father of Iynx[37] and, in another tradition, of Iambe.[38] By a nymph (whose name we are not told), he was, in one tradition, the father of Silenus, the leader of the satyrs.[39] And by an unnamed mother, he was the father of Eurymedon, who helped defend Thebes from the invasion of the “Seven against Thebes.”[40]

According to the epic poet Nonnus, Pan also had twelve children who, as “pans,” took after him. These children were named Celaeneus, Argennus, Aegicorus, Eugeneus, Daphoeneus, Omester, Phobus, Philamnus, Glaucus, Xanthus, Argus, and Phorbas. They joined the army of satyrs, silens, maenads, and other fantastic creatures that the god Dionysus led against India.[41]

Finally, some of the children ascribed to Faunus—Pan’s Italian counterpart—can also be included among the offspring of Pan. By the nymph Ismenis, for example, Pan/Faunus was the father of Crenaeus;[42] and by the nymph Symaethis, he was the father of Acis, the doomed lover of Galatea.[43]

Mythology

Origins

Though there is no evidence of Pan’s mythology prior to 500 BCE, it is likely that he was known in some form—at least in his native Arcadia—from a very early period, perhaps even as early as the Bronze Age. Pan may have emerged as a deity of the Mycenaean period (ca. 1600–1050 BCE) named “Aegipan” (Αἰγίπαν/Aigípan), a kind of goat god of shepherds.[44] Pan’s origins may also be connected with the early Indian god Pushan, whose name is cognate with his.[45]

Beginning in the early fifth century BCE, the cult of the Arcadian Pan began to spread throughout the Greek world, arriving at Boeotia[46] and Athens soon after. A famous story told of how Pan was not known in Athens until the eve of the first Persian invasion of Greece, in 490 BCE. The Athenians sent a runner, Phidippides, to seek the Spartans’ help. As he passed Tegea on his way back to Athens, Phidippides heard a voice asking him why the Athenians did not have a cult of Pan, even though he had helped them in the past and would help them again in the future. Soon after, the Athenians built a sanctuary to Pan on the Acropolis.[47] By the Hellenistic period (323–32 BCE), Pan was known and glorified in every corner of the Greek world (and beyond).

There were many different traditions surrounding the parentage and birth of the god Pan (see above). These conflicting accounts would have reflected competing local interests. One important source, the nineteenth Homeric Hymn (the Hymn to Pan), records the tradition that was popular in the Arcadian region of Mount Cyllene. In this version, Pan was born to Hermes and a daughter of Dryops. The bestial Pan terrified his mortal mother, but delighted Hermes:

And in the house [the daughter of Dryops] bare Hermes a dear son who from his birth was marvellous to look upon, with goat's feet and two horns—a noisy, merry-laughing child. But when the nurse saw his uncouth face and full beard, she was afraid and sprang up and fled and left the child. Then luck-bringing Hermes received him and took him in his arms: very glad in his heart was the god. And he went quickly to the abodes of the deathless gods, carrying his son wrapped in warm skins of mountain hares, and set him down beside Zeus and showed him to the rest of the gods. Then all the immortals were glad in heart and Bacchic Dionysus in especial…[48]

The Loves of Pan

The lascivious Pan was forever chasing after beautiful women and nymphs. Indeed, there were many myths about the god’s love affairs—though they characteristically ended in failure and frustration.

In one well-known tradition, Pan fell in love with the beautiful nymph Syrinx. Syrinx fled from him as far as the River Ladon, until she could go no further. Desperate, she called upon the gods to help her escape and was turned into river reeds. The sound of the wind blowing mournfully through these reeds inspired Pan, and he bound a few of the reeds together to fashion a new instrument. He called these pipes the “syrinx,” after the nymph who was forever lost to him.[49]

Pan and Syrinx by Jacob Jordaens (ca. 1620)

Epiarte Collection, MadridPublic DomainIn a similar story, Pan pined after the nymph Pitys, who, like Syrinx, fled from his advances. Eventually Pitys escaped Pan by transforming into a pine tree (pitys is the Greek word for “pine”).[50] But there was an alternative tradition in which Pan and Boreas, the god of the north wind, competed for Pitys’ affections. Jealous that Pitys preferred Pan to him, Boreas blew Pitys over a cliff. The gods then took pity on her and transformed her into a pine tree.[51]

Another object of Pan’s affections was Echo; several different versions of their myth have survived. In one account, Echo was a mortal girl who had been raised by nymphs and who had a hauntingly beautiful singing voice. Pan fell in love with her, but Echo rejected him. In revenge, Pan inspired some local herdsmen with his terrible “panic fear,” driving them to tear Echo apart limb from limb. Only her beautiful voice remained, forever imitating all the sounds of the woods.[52]

In most other versions of the myth, Echo was a mountain nymph rather than a mortal. Most of these versions also spared her such a gruesome ending: rather than being torn apart, Echo simply continued to flee from Pan, who for his part continued to pursue her.[53] But in some accounts, Echo and Pan did become lovers in the end and even had children together.[54]

Occasionally Pan was more successful in his pursuits. In one tradition, he managed to win the love of Selene, the goddess of the moon (though this story survives only in brief allusions and summaries). Apparently Pan seduced the goddess by either giving her a gift of sheep[55] or by covering himself in a sheepskin—perhaps another way of saying that he transformed himself into a sheep.[56]

The Music Contest

In one story, Pan—growing a bit too proud of his skill at playing the pipes—boasted that he was a better musician than even Apollo. Apollo challenged Pan to prove it in a music contest, in which Pan’s pipes—the syrinx—were pitted against Apollo’s lyre. Tmolus, an Anatolian mountain god, was appointed the judge.

After Pan and Apollo had both performed, Tmolus proclaimed Apollo the winner, and all the spectators approved this verdict—all except for Midas, who foolishly insisted that Pan should have been crowned the victor. Apollo punished Midas’ lack of taste by giving him huge, unsightly donkey ears.[57]

The Contest of Apollo and Pan by Sebastiano Ricci (ca. 1685–1687)

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VAPublic DomainThe Death of Pan

One strange story, recorded by the Greek author Plutach, refers obscurely to the death of Pan. During the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius (14–37 CE), an Egyptian helmsman named Thamus heard a voice commanding him to cry out “the great Pan is dead” as he sailed past the Palodes (located somewhere in Anatolia, perhaps around modern Albania). This sailor did as he was told, and in response a loud wail arose from the countryside.[58]

Though Pan was a relatively minor deity, there is no reason to think he would have been mortal. It is also strange that his death should be so strongly connected with Anatolia in the East, when the god was native to Arcadia in the Peloponnese. It is possible that Plutarch somehow confused Pan with Tammuz, the archetypal dying god of Near Eastern lore (hence the name of the Egyptian helmsman).

Other Interpretations

There were other important interpretations of the god Pan in antiquity. In philosophy, especially Stoic philosophy, Pan was seen as the embodiment of the universe—a notion that arose from the pseudo-etymological link between Pan’s name and the Greek tò pân, meaning “everything, universe.”[59]

A similar view of Pan was adopted in Orphism, an ancient Greek religion with its own distinctive beliefs, rituals, and pantheon. In Orphism, Pan was regarded as the god of “everything.”[60]

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

Pan had sanctuaries throughout the ancient world, most of which were built into caves and grottoes. Some of his most important sanctuaries were located in Arcadia, where the god’s cult apparently originated; in the Lycaean Mountains, for instance, there was a shrine to Pan,[64] as well as an oracular site.[65]

Pan’s cult was also known at other major sites. The Corycian Cave in Delphi, for instance, was dedicated to Pan and the nymphs.[66] In Athens, Pan had a grotto on the northern slope of the Acropolis.[67] Elsewhere in Attica, Pan shared a shrine with the nymphs on the banks of the Ilissus River[68] and enjoyed a cult in Phyle.[69] Pan was also worshipped further away, and the remains of his temple at Apollonopolis Magna in Egypt can still be seen today.

Festivals and Holidays

Some festivals of Pan were documented in antiquity. In Athens, for example, Pan was honored annually with sacrifices and a torch race. But he was most often worshipped in an individual, private capacity. Shepherds would sacrifice kids (i.e., young goats) in his honor,[70] as well as other animals. They would also dedicate statuettes and other votive offerings (vases, lamps, and so on) at the shrines of Pan.

Terracotta oil lamp with relief of a mask of Pan (first half of 1st century CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainSome rituals connected with Pan were more surprising or strange. On the island of Psyttalea near Attica, Pan was regarded as the patron god of Athenian fishermen.[71] In Arcadia, young men would ceremonially beat a statue of Pan after unsuccessful hunts.[72]

Pop Culture

Despite the reports of his death, which were already circulating in antiquity, Pan has remained alive and well in the popular imagination. Beginning in the Middle Ages, the lecherous Pan influenced the Christian concept of the devil, and the resemblance between Pan and Satan remains prevalent today, especially among occultists.

Since the nineteenth century, Pan has been a popular figure in literature and art, featuring in numerous novels, poems, paintings, and sculptures. For instance, he is the “Piper at the Gates of Dawn” in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908).

Pan has become closely associated with neopaganism, especially after the publication of Margaret Murray’s The God of the Witches in 1933. A number of modern proponents of witchcraft and the supernatural claim to have encountered Pan. Between the Christian devil and neopaganism, today’s Pan is an altogether more sinister being than the piping, fun-loving woodland god of the ancient Greeks.