Silenus

Silenus and the Four Seasons by Jacob Jordaens (ca. 1600–1700).

Musée Ingres BourdellePublic DomainOverview

Silenus was one of the satyrs or silens, a race of drunken woodland creatures who served as companions of the god Dionysus. Silenus was the oldest of these creatures and was often regarded as their leader or father. He was known for bridging the fine line between intoxication and wisdom: when drunk, he acquired the power of prophecy. Mortals (like the Phrygian king Midas) would sometimes capture him to learn his wisdom.

Silenus was represented as a jovial old man with a bald head, snub nose, and round paunch. Like the other satyrs or silens, he sported the ears, tail, and (in some depictions) hind legs of a horse. He was worshipped and honored largely in connection with Dionysus, whom he was said to have tutored. But Silenus also had some cults of his own, especially in Attica.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Silenus” (Greek Σιληνός, translit. Silēnós) is unknown. Some have argued that it comes from an Indo-European word meaning “wine.”[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Silenus Σιληνός (translit. Silēnós) / Σειληνός (translit. Seilēnós) Phonetic

IPA

[sahy-LEE-nuhs] /saɪˈli nəs/

Titles and Epithets

In Greek mythology, Silenus was one of the oldest and most revered of the satyrs or silens (the terms were usually interchangeable). He was often represented as the father of these creatures and was therefore called Παπποσείληνος (Papposeílēnos), “Daddy Silenus.”[2]

In some parts of the Greek world, Silenus had other special names and titles. In Malea in the southern Peloponnese, for example, he was called Πύρριχος (Pýrrichos), “the fiery one.”[3]

Attributes

Appearance and Abilities

Silenus, like the other satyrs and silens, was typically imagined with the ears, tail, and occasionally legs and coat of a horse (or goat). He tended to be bald and snub-nosed and was often depicted naked, with a large erect penis. Sometimes he was represented with horns.[4] It seems that Silenus was immortal (though not all satyrs and silens were).

Silenus was most commonly seen in the company of Dionysus, the god of wine and intoxication. He shared the other satyrs’ love of sleep, sex, music, dancing, and, of course, wine.[5] Since he was constantly drunk, he was usually shown riding a wild donkey or supported by other satyrs.

Attic red-figure psykter (wine cooler) showing Satyrs or Silens engaged in a highly acrobatic komos (revel). Signed by Douris (ca. 500–490 BCE). British Museum, London, UK.

Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainBut Silenus was also known for his wisdom and prophetic abilities—attributes that sometimes made him a target. When drunk, he was vulnerable to capture by humans, who would bind him with garlands and demand knowledge and prophecies.[6]

Iconography

Satyrs and silens were often represented in ancient art, though usually as a large merry band or alongside Dionysus, not individually. Silenus, however, does stand out in some representations.

Like other satyrs and silens, Silenus was shown with the ears and tail of a horse, and sometimes (though more rarely) with the hind legs of a horse. Also like the other satyrs and silens, Silenus had a balding head, snub nose, and scraggly hair and beard. His distinctive appearance was often compared to the philosopher Socrates, who, like Silenus, was seen as having an ugly outer shell that concealed a beautiful and divine essential nature.[7]

Silenus’ attributes in art included a swollen wineskin, musical instruments, furs, and a wild donkey. Beginning in the fifth century BCE, due to the growing influence of the satyr play, Silenus was often depicted as the leader of the satyrs in a variety of mythical scenes. One important image, preserved in several copies of an original sculpture from the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE), shows Silenus holding the infant Dionysus.

Marble statue of Silenus holding the infant Dionysus. Roman copy (mid-second century CE) after early Hellenistic original, perhaps by the school of the sculptor Lysippus (ca. 300 BCE). Vatican Museums, Vatican, Italy.

JastrowPublic DomainSilenus, along with other satyrs and silens, remained popular in Roman art, including on reliefs, punch bowls, and sarcophagi.[8]

Family

Family Tree

Origins

Silenus’ mythical origins are obscure; several different versions of his parentage were known in antiquity (see above). As with the other satyrs, Silenus was closely connected with the god Dionysus. And since Dionysus was commonly said to have been born and brought up on Mount Nysa,[21] Silenus was also sometimes connected with Nysa. One tradition even claimed that Silenus was the first king of Nysa.[22] In other traditions, however, Silenus came from a different part of the Greek world, such as Malea in the Peloponnese.[23]

Historically, we do not hear of satyrs or silens in ancient Greece until a relatively late period (seventh or sixth century BCE). Silenus himself seems to have been popularized by the development of a new dramatic genre, the satyr play, around the middle of the fifth century BCE. In these plays, Silenus leads a chorus of satyrs in a kind of mythological burlesque.

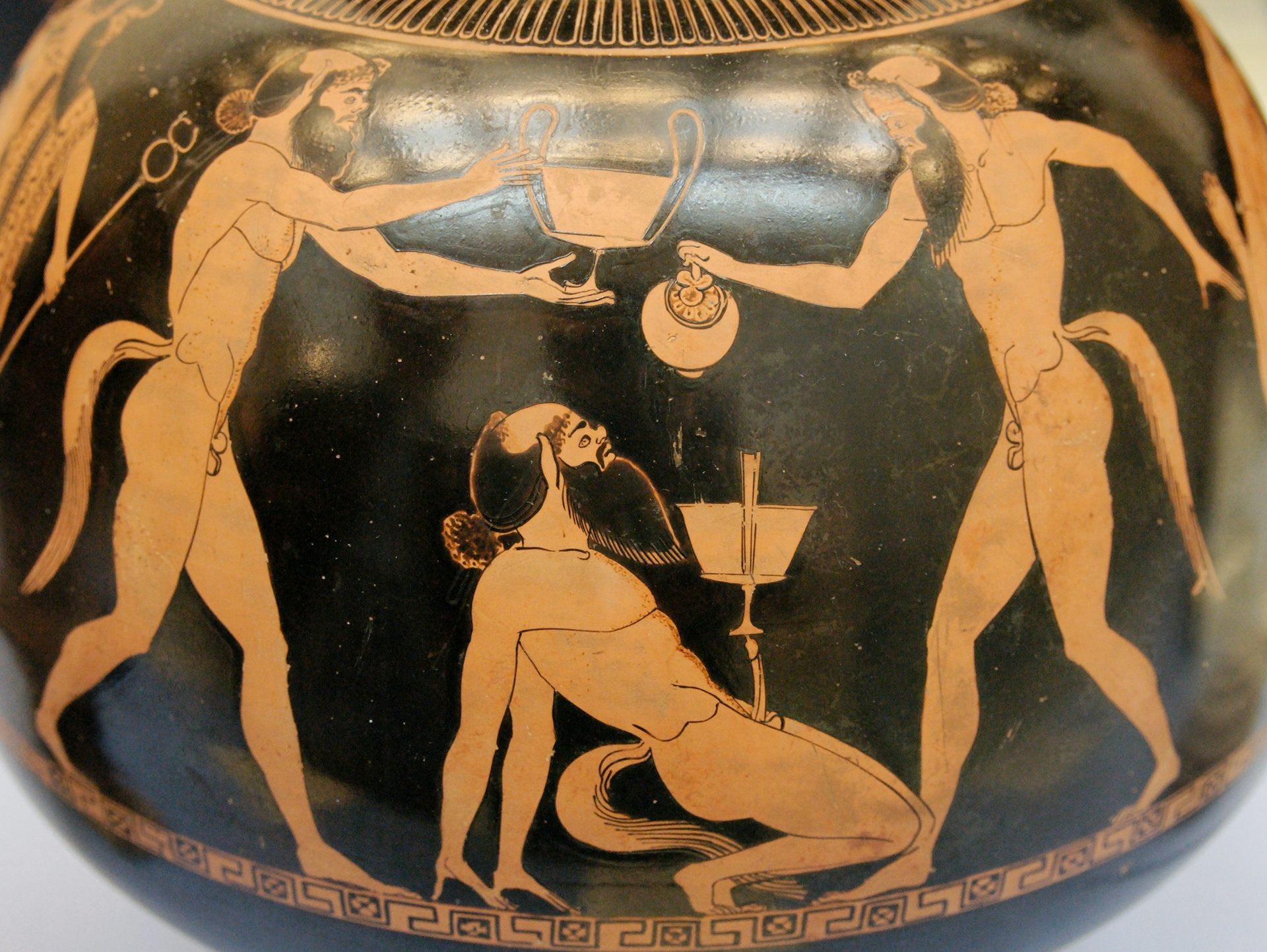

Etruscan red-figure stamnos (liquid container) showing a drunk Papposilenus (center) supported by two Satyrs. From Vulci (ca. 300 BCE). Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainOver time, there arose a tradition in which Silenus tutored the young Dionysus. This was likely modeled on the myth of the Centaur Chiron, who tutored many important heroes. Soon, the image of a wise Silenus began to emerge and acquire its own literature and mythology.

Silenus and Dionysus

Like many gods, Dionysus was born under strange circumstances: he emerged from the thigh of his father Zeus after his mother Semele was killed while still pregnant with him. Zeus needed somebody to care for and raise his young son, and that task was given (at least in some versions) to Silenus.[24]

Raising the wild Dionysus naturally presented challenges. As he was an illegitimate child of Zeus, Dionysus was despised by Zeus’ wife Hera, who repeatedly tried to destroy him. In his youth, Dionysus went mad and wandered the world: he was kidnapped by pirates, conquered India, and eventually became the god of wine.

Silenus and the other satyrs accompanied Dionysus on his misadventures, alternately keeping him safe and egging him on. When Dionysus became one of the Olympian gods, Silenus and the other satyrs and silens remained his most loyal followers, even fighting beside him when the Giants attacked Mount Olympus.

In Euripides’ Cyclops, Silenus—quite understandably—groans about all the trouble Dionysus put him through:

O Bromius,[25] labors numberless have I had because of you, now and when I was young and able-bodied! First, when Hera drove you mad and you went off leaving behind your nurses, the mountain-nymphs; next, when in the battle with the Earthborn Giants I took my stand protecting your right flank with my shield and, striking Enceladus with my spear in the center of his target, killed him. (Come, let me see, did I see this in a dream? No, by Zeus, for I also displayed the spoils to Dionysus.) … when Hera raised the Tuscan pirates against you to have you sold as a slave to a far country, I learned of it and took ship with my sons to find you. Taking my stand right at the stern, I myself steered the double-oared ship, and my sons, sitting at the oars, made the grey sea whiten with their rowing as they searched for you, lord.[26]

Midas and the Wisdom of Silenus

Perhaps the most famous myth of Silenus tells of how he was captured by the Phrygian king Midas, who wished to learn his wisdom. Midas bound Silenus while he was asleep (in some versions, Midas had caused Silenus to fall asleep by lacing his fountain with wine) and took him hostage.

Once he had him in his clutches, Midas begged Silenus to share his wisdom. Silenus resisted at first. But when Midas persisted in his questioning, the satyr at last relented. His wisdom was very bleak: according to Silenus, the best thing for a human being was never to be born at all, and the second best was to die as soon as possible.[27]

In another account, Midas found Silenus lost in his lands after Dionysus and his band had passed through. The king played the generous host, feasting and partying with Silenus for many days. When Dionysus came searching for his old tutor, Midas safely returned Silenus to him. Dionysus, wishing to reward Midas, allowed the king to ask for anything he pleased. The greedy Midas wished that everything he touched would turn to gold—the infamous “Midas touch.”[28]

The Triumph of Bacchus by Cornelis de Vos (seventeenth century).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOther Myths

A smattering of other myths were sometimes told about Silenus.

Some traditions made Silenus the inventor of the panpipes (apparently confusing or conflating him with the satyr Marsyas).[29] In one of his Eclogues, Virgil tells a story very similar to that of Silenus and Midas, in which two shepherds bind Silenus while he is sleeping and force him to regale them with a fabulous song.[30] Silenus was also closely connected with the town of Pyrrhichus in Laconia, whose people claimed that the wise and fun-loving old creature had given them their well as a gift.[31]

Silenus, along with the other satyrs, found his way into virtually all Greek myths through the burlesque satyr plays performed in classical Athens. In Euripides’ Cyclops (the only complete surviving satyr play), Silenus and the satyrs help Odysseus and his men escape from the Cyclops Polyphemus; in Aeschylus’ Net-Haulers, they fish Danae and the infant Perseus from the sea;[32] in Sophocles’ Trackers, they search for the cattle that the infant Hermes had stolen from his brother Apollo.[33]

Though Silenus was technically immortal, one tradition (recorded in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca) related his demise. As the story goes, Silenus got himself into a dancing contest while traveling with Dionysus in Assyria. Alas, Silenus lost, and when he sank to the ground in exhaustion, he was transformed into a river.[34]

Worship

Silenus was worshipped above all in Attica,[35] but he also had cults in other parts of the Greek world. For instance, he was closely connected with Pyrrhichus and Malea in the Peloponnese.[36] Silenus also had a temple of his own—not shared with Dionysus—in Elis in the western Peloponnese. This temple contained a cult statue showing Methe, the personification of drunkenness, handing Silenus a cup of wine.[37]

Pop Culture

Silenus is no longer as familiar as he once was and rarely appears in modern adaptations of Greek mythology. He has, however, been featured in some contemporary literary works. Silenus is a character, for instance, in Tony Harrison’s The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus (1990), a modern satyr play inspired by the discovery of the large fragments of Sophocles’ satyr play Trackers. Silenus is also the inspiration behind the character of Professor Silenus in Evelyn Waugh’s 1928 novel Decline and Fall.