Typhoeus

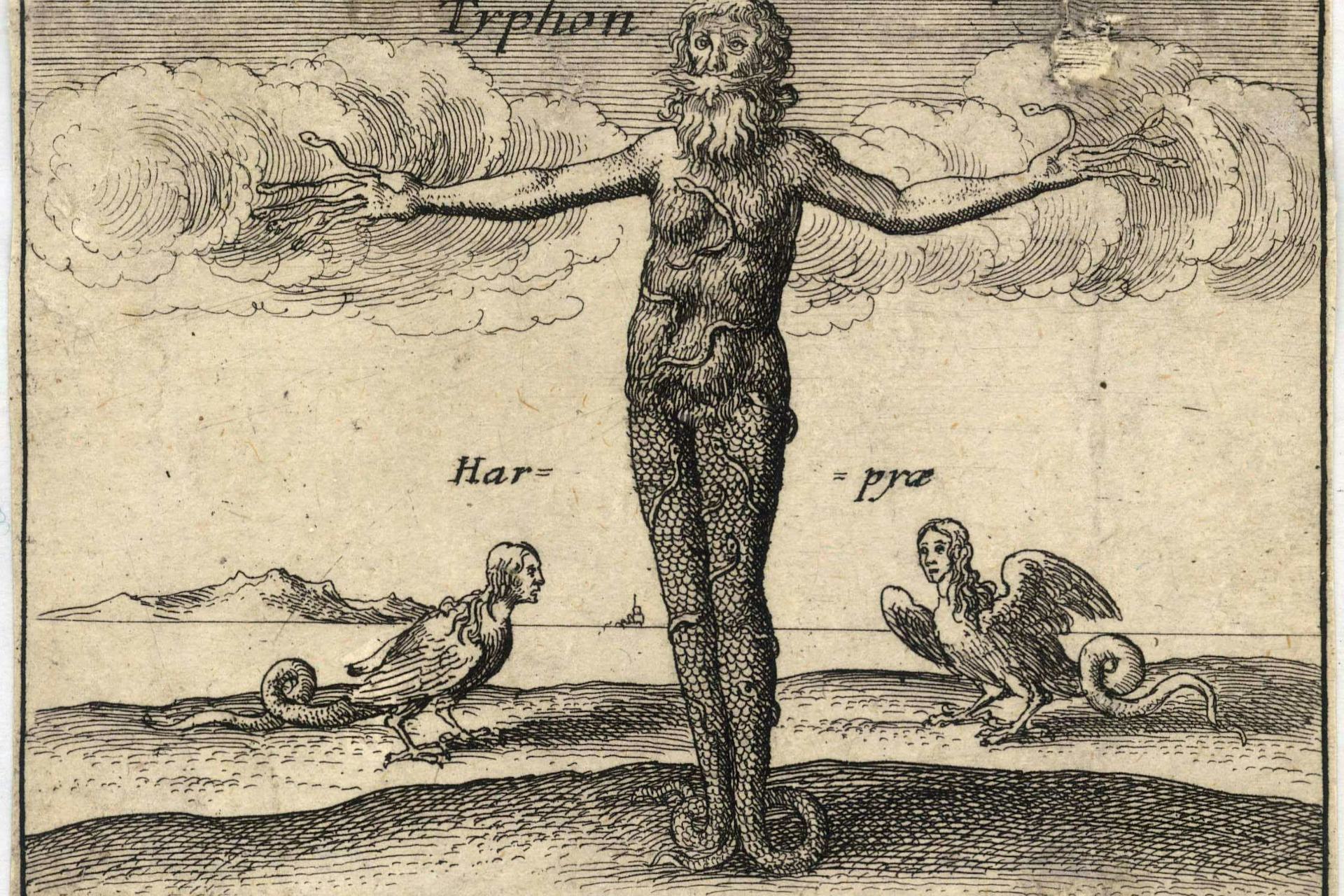

The Greek gods. Typhon. by Wenceslaus Hollar (n.d.)

University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital CollectionPublic DomainOverview

Typhoeus, also called Typhon, was a terrible monster and the last of Zeus’ challengers. His mother was usually said to be Gaia, the primordial goddess of the earth, but there were other traditions in which he was the son of Hera, Zeus’ own wife.

Descriptions of Typhoeus’ appearance varied greatly; most traditions made him a many-headed or many-limbed monster of incredible size and strength who was able to breathe fire. With his mate Echidna, another fierce monster, Typhoeus begot several creatures terrifying to mortals and gods alike, including Cerberus, the Hydra, and the Chimera.

Typhoeus himself was born to challenge Zeus, the ruler of the Olympians. Though the monster was ultimately defeated, in some accounts he almost overpowered Zeus and even managed to cripple him. The defeated Typhoeus was imprisoned beneath the earth, and the fire and smoke that poured from the volcanoes of Etna or Vesuvius were sometimes said to be caused by his thrashing as he struggled to burst free.

Etymology

The etymology of “Typhoeus” (Greek Τυφωεύς, translit. Typhōeús) is uncertain. Some have suggested that the name was derived from the Greek verb τύφομαι (týphomai), meaning “to smoke, smoulder, glow” or “to make smoke, smoulder, glow.” It may also be derived from the related noun τῦφος (tŷphos), which translates to “smoke, fumes” but also “whirlwind.”[1] This would make Typhoeus into a kind of “whirlwind” or “typhoon” god.[2]

Another theory has linked the name to the Indo-European root *dhubh-n-, meaning “abyss.”[3]

Some scholars, however, argue that the name has Semitic roots. Martin West, for example, has suggested that Typhoeus may have originated from the word ṣp̄n, meaning “north.” This word was used as a local epithet of the Ugaritic god Baal (“Baal Sapon”) in connection with his cult on Mount Casius, on the border between Syria and Turkey.[4]

Mount Casius (modern Jebel Aqra) on the Syria-Turkey border. The Greek myth of Typhoeus may have originated in the Ugaritic god Baal Sapon, worshipped in antiquity on Mount Casius.

AthiokCC BY-SA 3.0None of these etymological explanations has been universally accepted by scholars, and the true origins of Typhoeus’ name are likely to remain unknown.[5]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Typhoeus; Typhon Τυφωεύς (translit. Typhōeús); Τυφῶν (translit. Typhôn) Phonetic

IPA

[TAHY-fee-uhs]; [TAHY-fon] /taɪˈfiːəs/; /ˈtaɪ fɒn/

Alternate Names

The name “Typhoeus” existed in several interchangeable forms. The most common of these was probably “Typhon” (Greek Τυφῶν, translit. Typhôn), which had become the standard version of the name by the fifth century BCE. But other alternatives existed, too, including Τυφάων (Typháōn) and Τυφώς (Typhṓs).[6]

Titles and Epithets

Though Typhoeus was a sibling of the Titans and the Giants, he was not considered a member of those groups himself—at least not in the standard accounts of his mythology. In later periods, however, the Romans sometimes referred to him as a Titan or a Giant.[7]

Attributes

Locales

Typhoeus was connected with several locales in the ancient world. Some can be easily located, while others remain mysterious.

His birthplace was usually said to be Cilicia, a region in what is now southeastern Turkey.[8] In one source, however, Typhoeus seems to have been brought up not in Asia but in Delphi, in central Greece—the site of Apollo’s famous oracle.[9]

After he was defeated by Zeus, Typhoeus was buried somewhere beneath the earth. Hesiod, the earliest author to tell the story, says simply that Typhoeus was cast into Tartarus.[10] But other sources were more specific. The most popular tradition claimed that Typhoeus was buried under Mount Etna (also spelled Aetna) in Sicily, causing volcanic eruptions as he struggled to get free:

Once the famous Cilician cave nurtured him, but now the sea-girt cliffs above Cumae, and Sicily too, lie heavy on his shaggy chest. And the pillar of the sky holds him down, snow-covered Aetna, year-round nurse of bitter frost, from whose inmost caves belch forth the purest streams of unapproachable fire. In the daytime her rivers roll out a fiery flood of smoke, while in the darkness of night the crimson flame hurls rocks down to the deep plain of the sea with a crashing roar. That monster shoots up the most terrible jets of fire; it is a marvellous wonder to see, and a marvel even to hear about when men are present. Such a creature is bound beneath the dark and leafy heights of Aetna and beneath the plain, and his bed scratches and goads the whole length of his back stretched out against it.[11]

Mount Etna in Sicily, whose eruptions were sometimes said to be caused by the underground thrashing of the imprisoned Typhoeus.

BenAvelingCC BY-SA 4.0Other writers connected Typhoeus with Ischia, another volcanic island off the coast of Italy.[12] Indeed, some said that he was buried beneath Ischia rather than Etna.[13]

But the earliest literary references to Typhoeus stated that the monster was buried in a place known either as Arima, Arimon, or the land of the Arimi—sometimes called the “bed” of Typhoeus.[14] Its location was mysterious even to the ancients. Some sources seemed to place it somewhere in Cilicia, where Typhoeus was born.[15] But others identified the land of the Arimi with either Lydia, Catacecaumene in Mysia, Hyde (possibly another name for Sardis), Syria, or Ischia.[16]

Other possible locations for Typhoeus’ eternal underground prison included Lake Serbonis in Egypt[17] or various regions in Asia Minor, including Lydia, Phrygia, or Typhoeus’ own birthplace of Cilicia.[18]

Finally, Typhoeus appears to have been vaguely connected with the central Greek region of Boeotia. One source mentions a place there called Typhaonium;[19] another writes of a mountain peak called Typhon.[20] One source even listed Boeotia among the places where Typhoeus may have been imprisoned.[21]

Appearance and Abilities

Descriptions of Typhoeus’ appearance and abilities varied considerably across ancient sources. He was usually represented as a very large monster with many heads, serpentine features, and the ability to breathe fire.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Typhoeus is described as having 100 snake heads, fiery eyes, the ability to either breathe fire or shoot fire from his eyes (the Greek is unclear), and a terrifying voice capable of mimicking the sounds of various animals (human speech, the bellowing of bulls, the roaring of lions, and so on):

Strength was with his hands in all that he did and the feet of the strong god were untiring. From his shoulders grew a hundred heads of a snake, a fearful dragon, with dark, flickering tongues, and from under the brows of his eyes in his marvellous heads flashed fire, and fire burned from his heads as he glared. And there were voices in all his dreadful heads which uttered every kind of sound unspeakable; for at one time they made sounds such that the gods understood, but at another, the noise of a bull bellowing aloud in proud ungovernable fury; and at another, the sound of a lion, relentless of heart; and at another, sounds like whelps, wonderful to hear; and again, at another, he would hiss, so that the high mountains re-echoed.[22]

Other early writers also tended to describe Typhoeus with 100 heads,[23] though some gave him 50.[24] Some added further attributes: that Typhoeus breathed fire;[25] that he had a terrible, shrieking voice and flashing eyes;[26] that when he was injured, creatures of all kinds were born from his blood;[27] and that snakes grew from his thighs and other parts of his body.[28]

Artists from this period, though, tended to simplify Typhoeus’ form (perhaps because it was much easier to describe a hundred-headed, serpent-generating, multi-voiced monster than it was to represent him visually). In painting and sculpted reliefs, Typhoeus was usually shown with the head and torso of a man and snakes for legs.

In later sources—from around the first century CE on—descriptions of Typhoeus became, if anything, even more outlandish. Ovid wrote that he had 100 hands.[29] Nonnus raised the number of hands to 200 and embellished upon his attributes in many other ways: his Typhoeus had the heads of many different animals growing from his shoulders, including snakes, leopards, and the head of a man in the middle; he had a lion’s mane and a bull’s horns; and he made monstrous noises and spat venom.[30]

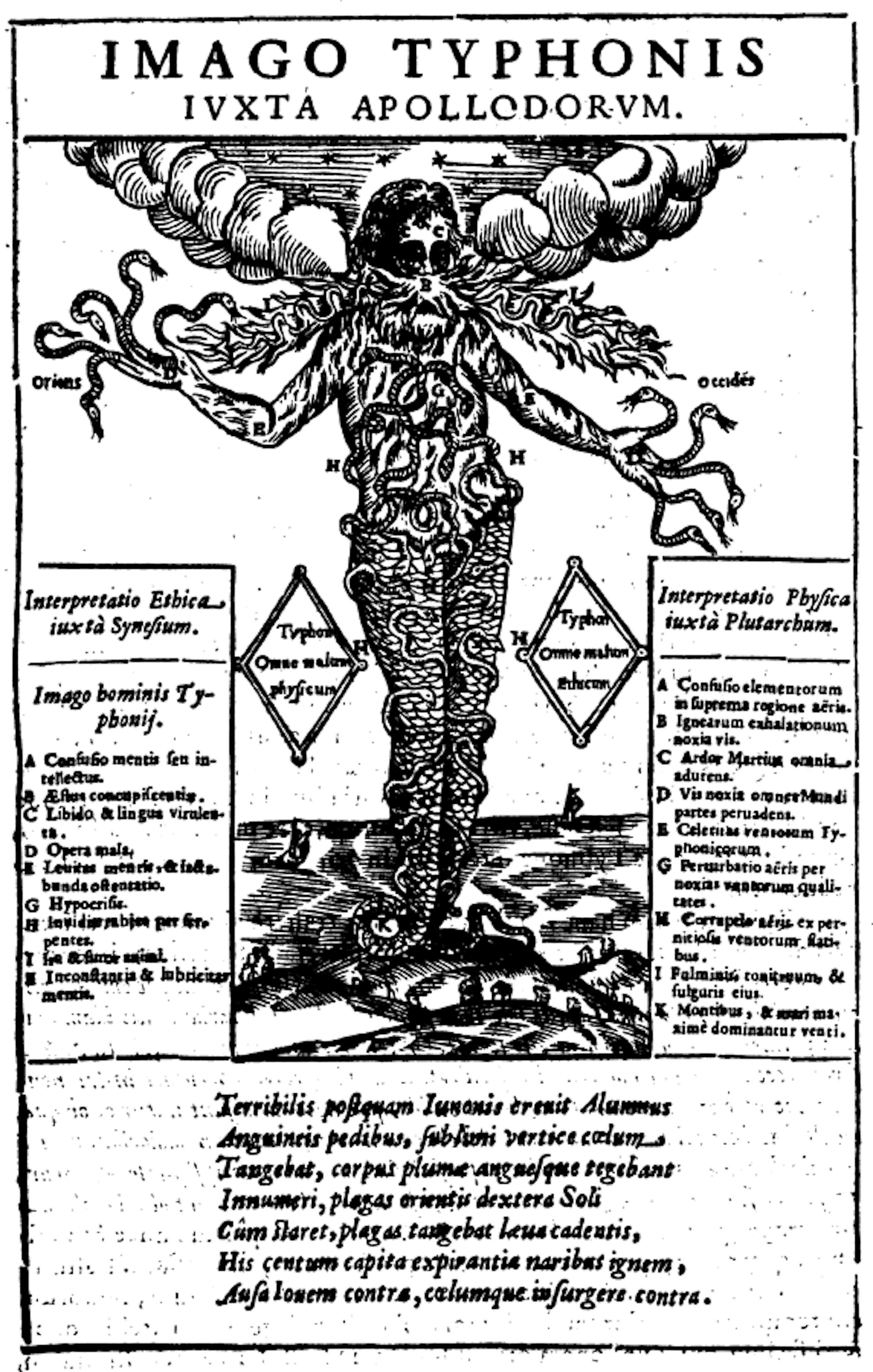

Another striking description of Typhoeus comes from Apollodorus’ Library:

As far as the thighs he was of human shape and of such prodigious bulk that he out-topped all the mountains, and his head often brushed the stars. One of his hands reached out to the west and the other to the east, and from them projected a hundred dragons’ heads. From the thighs downward he had huge coils of vipers, which when drawn out, reached to his very head and emitted a loud hissing. His body was all winged: unkempt hair streamed on the wind from his head and cheeks; and fire flashed from his eyes.[31]

Illustration of Typhoeus (Typhon) after the description in Apollodorus’ Library by Athanasius Kircher.

Oedipus AegyptiacusPublic DomainIconography

Typhoeus was occasionally pictured in ancient art, albeit in a somewhat simplified form: he usually had a man’s head and upper body, snake legs or a fish tail, and wings (or some variation of those attributes). He was sometimes depicted alone but was most recognizable in scenes that showed him battling a lightning-wielding Zeus.[32]

Family

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mothers

Siblings

Brothers

Sister

Consorts

Wife

Children

Daughters

Sons

- Cerberus

- Orthus

- Nemean Lion

- Lesser Anemoi

Mythology

Origins

Typhoeus’ mythology may have originated in the Near East. The ancient Greeks associated him with eastern locales such as Cilicia, Syria, Mount Casius, and the Orontes River. They also connected Typhoeus with the Egyptian gods—most notably Seth, the traditional enemy of Osiris (in later periods, we even encounter a Greco-Egyptian deity called “Typhon Seth”).[48]

The battle between Zeus and Typhoeus has parallels in Near Eastern mythologies, where we hear of several heroes or storm gods (like Zeus) fighting terrible monsters (like Typhoeus) in order to cement their power. Examples include the battle between the hero-god Ninurta and the monsters Asag[49] and Anzu in Mesopotamian mythology;[50] the battle between the god Baal Sapon and the sea monster Yam in Ugaritic mythology;[51] the battle between the storm god Teshub and the stone monster Ulikummi in Hurrian mythology;[52] and the battle between the storm god Tarhunna and the monster Illuyanka (themselves counterparts of the Hurrian Teshub and Ulikummi) in Hittite mythology.[53]

Hittite relief showing the storm god Tarhunna killing Illuyanka (ca. 850–800 BCE).

Georges JansoonCC BY-SA 3.0Strikingly, several of these mythical battles occurred in the same place: Mount Casius in northern Syria. Also striking is the fact that these eastern myths—like the Greek myth of Typhoeus—tended to serve as the end of a “succession myth,” describing the final battle in a series of contests for control of the cosmos. This suggests that many, if not all, of these myths shared a common origin in the Near East.

Birth

Typhoeus was born to challenge Zeus’ supremacy. Zeus had come to rule the Olympians and the entire cosmos after defeating his father Cronus and his Titan siblings. But he had somehow angered Gaia in the process (the details of this offense are unclear). Desiring to punish or even overthrow Zeus, Gaia sought an avenger.

In the most familiar accounts, Gaia gave birth to this avenger, Typhoeus, herself.[54] But even in the traditions in which Typhoeus had different parents, Gaia tended to be involved in the monster’s conception.

In one account, possibly drawn from Orphic beliefs, Gaia slandered Zeus to his wife Hera, who resolved to give birth to a child who would destroy Zeus. As part of this plot, she went to Cronus, her Titan father, who gave her two eggs smeared with his semen. Hera buried these in Cilicia, and from them Typhoeus was born. (Hera, however, had come to regret her rebellious actions and revealed the plot to Zeus, who promptly came to Cilicia to destroy Typhoeus.)[55]

In another version, known from very ancient texts, Hera was jealous that Zeus had given birth to a daughter, the goddess Athena. Thus, she decided to give birth to a child on her own (through parthenogenesis): she pounded the earth with her hands and the earth goddess Gaia caused her to become pregnant with Typhoeus. When Typhoeus was born, he was sent to be raised by the female dragon of Delphi (later identified with the male serpent Python).[56]

The Battle Between Typhoeus and Zeus: Two (or More) Versions

The Short Version: Hesiod’s Typhoeus

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, the earliest account of the myth, Typhoeus challenged Zeus to a battle as soon as he was fully grown. Zeus complied, setting out to meet the monster with his great lightning bolts. Fearsome as Typhoeus was, Hesiod’s Zeus defeated him quickly and without too much difficulty:

[Zeus] thundered hard and mightily: and the earth around resounded terribly and the wide heaven above, and the sea and Ocean’s streams and the nether parts of the earth. Great Olympus reeled beneath the divine feet of the king as he arose and earth groaned thereat. And through the two of them heat took hold on the dark-blue sea, through the thunder and lightning, and through the fire from the monster, and the scorching winds and blazing thunderbolt. The whole earth seethed, and sky and sea: and the long waves raged along the beaches round and about at the rush of the deathless gods: and there arose an endless shaking… So when Zeus had raised up his might and seized his arms, thunder and lightning and lurid thunderbolt, he leaped from Olympus and struck him, and burned all the marvellous heads of the monster about him. But when Zeus had conquered him and lashed him with strokes, Typhoeus was hurled down, a maimed wreck, so that the huge earth groaned.[57]

Zeus then imprisoned the defeated Typhoeus underneath the earth, in Tartarus. Some sources added that he piled a mountain (usually Mount Etna) on top of him.

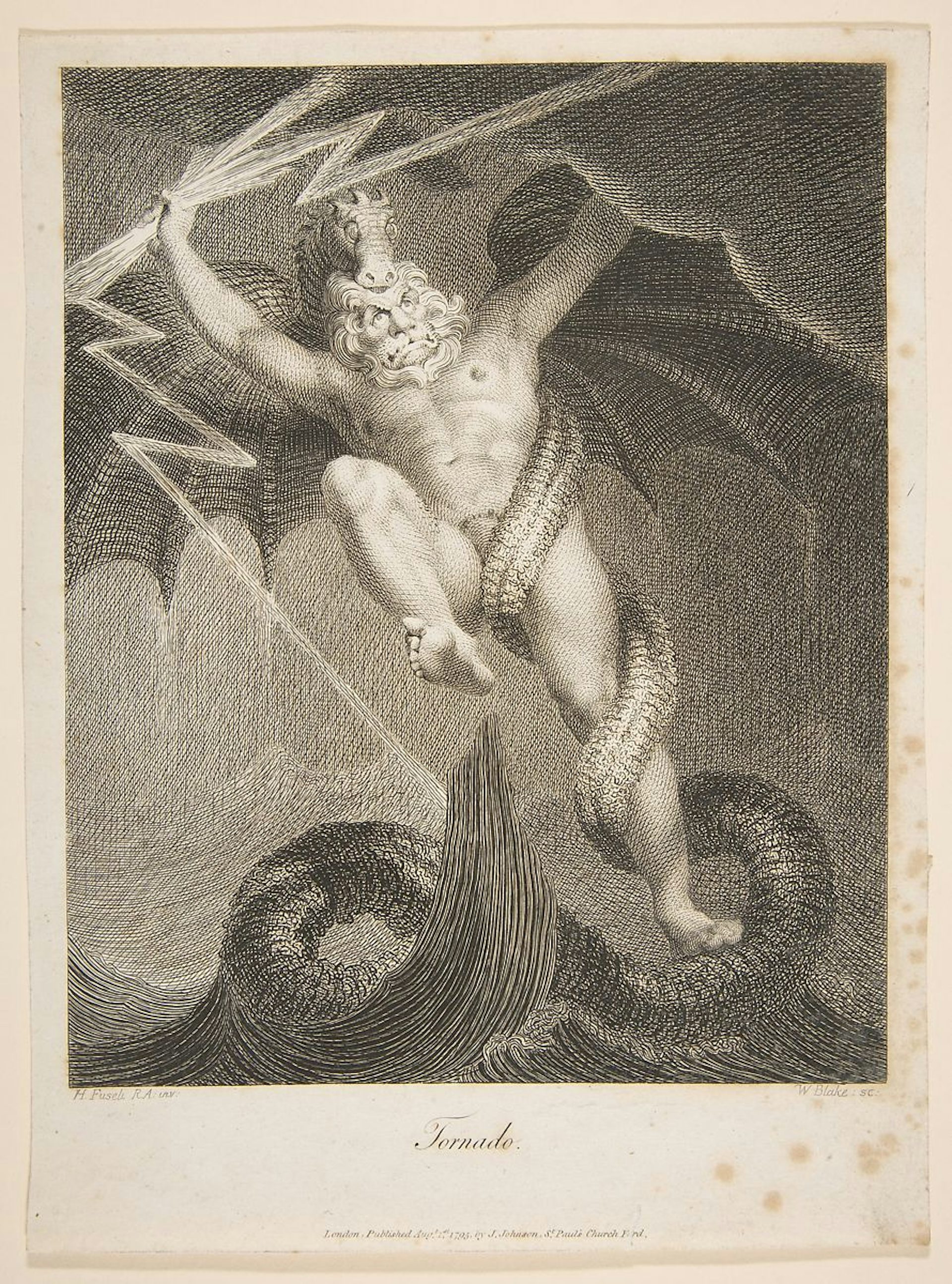

Tornado-Zeus Battling Typhon by William Blake, from Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden (1795).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Long Version: Apollodorus, Nonnus, and Others

This was by no means the only version of the battle between Zeus and Typhoeus. One notable alternative tradition seems to be much closer to its Near Eastern parallels and may well represent the earliest account of Typhoeus’ myth.

This version generally begins with Typhoeus launching a fierce attack upon the gods. To escape him, the gods transformed themselves into animals and fled to Egypt. In most accounts, only Zeus and Athena did not change forms (though some sources claim that Zeus did transform into a ram and join the other gods in flight).[58] This remarkable myth was presumably meant to explain the “zoomorphism” (that is, the animal attributes) of the Egyptian gods.[59]

According to Apollodorus’ Library and Nonnus’ Dionysiaca—the most complete accounts of this version of the myth—Zeus was actually almost defeated by Typhoeus. In their first battle, Typhoeus managed to overpower Zeus (in one version, he stole Zeus’ main weapon, his lightning bolts). He then took the sinews of Zeus’ hands and feet and hid them.

The crippled Zeus was saved through the trickery of his friends, though there are different accounts of what exactly happened. In one, the gods Hermes and Aegipan stole back his sinews from the female dragon Delphyne, whom Typhoeus had entrusted with the body part. In another, it was the Theban hero Cadmus and the rustic god Pan who stole back the sinews, distracting Typhoeus with music.

At any rate, Zeus was magically restored once he had his sinews back and quickly renewed his attack on Typhoeus. Another vicious battle erupted; in some traditions, other gods became involved (the Moirae or Eos on the side of Zeus, Gaia on the side of Typhoeus). In the end, Zeus chased Typhoeus to Sicily and buried him beneath Mount Etna.[60]

Though the sources recording this tradition were all written at a relatively late date (many centuries after Hesiod’s Theogony), it is likely that they preserve the original version of Typhoeus’ myth—one that is closer to the Near Eastern myths from which he was probably derived.

Among other things, the reference to Mount Casius (found in Apollodorus’ account) ties Typhoeus closely to both Ugaritic and Hurrian mythology, both of which tell of a battle between a storm god and a monster set upon this very mountain. And Typhoeus’ initial defeat of Zeus finds a parallel in the Hittite myth of the battle between Tarhunna and Illuyanka, where Illuyanka wins his first fight against Tarhunna—and even steals some of Tarhunna’s body parts to weaken him (just as Typhoeus steals Zeus’ sinews)—before being defeated in his second battle with the restored Tarhunna.

Other Versions

There seem to have been other versions of the battle, too. Some authors described how Typhoeus tried to escape from Zeus, with Zeus burning up huge swathes of land (including the whole of the Caucasus) as he pursued him.[61] One account related that Typhoeus tried to sneak into Zeus’ palace while he slept and was struck down when Zeus woke up and caught him.[62]

Pop Culture

Typhoeus was one of the most variable figures in ancient Greek mythology: details of his appearance, powers, dwelling place, parentage, and myth diverged widely. It is probably no surprise, then, that modern visions of Typhoeus have continued to vary.

In Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, for example, Typhoeus (called “Typhon”) appears a few times and is represented as a vast, dragon-like monster. In the TV show Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, on the other hand, Typhoeus (again called “Typhon) is a Giant—essentially just an impossibly tall human—who, in stark contrast to his bellicose mythical namesake, is represented as surprisingly reasonable and likable.