Eros

The Abduction of Psyche by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1895).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOverview

Lovely Eros personified love, passion, and procreation. He was originally imagined as a primordial god who emerged at the dawn of creation, alongside Chaos, Gaia, and Tartarus. However, he was soon reinvented as the son of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, and was usually represented as her constant companion. Some later authors even introduced multiple “Erotes,” all of them somehow connected to Aphrodite and love.

Eros was a mischievous and unruly god who could sometimes be cruel. His arrows, which he launched from a golden bow, roused overpowering love and passion. Once pierced by these arrows, nobody—not even the all-powerful Zeus—could resist Eros. In one late story, Eros eventually fell victim to his own power when he developed a hopeless passion for the beautiful Psyche.

Etymology

The name “Eros” (Greek Ἔρως, translit. Érōs) is the Greek word meaning “passion” or “romantic love.” However, the etymology of this word is unknown; it may be pre-Greek.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Eros Ἔρως (Érōs) Phonetic

IPA

[EER-os, ER-os] /ˈɪər ɒs, ˈɛr ɒs/

Alternate Names

Eros’ Roman counterpart was called Cupido (Cupid) or Amor.

Titles and Epithets

Eros’ epithets include καλός (kalós,“lovely, beautiful”), κάλλιστος (kállistos, “loveliest, most beautiful”), χρυσοκόμης (chrysokómēs, “golden-haired”), and λυσιμελής (lysimelḗs, “limb-loosening”). The poet Sappho famously described him as γλυκιπικρός (glykypikrós, “bittersweet”).[2]

Attributes

Functions and Characteristics

Eros was the god who personified love, passion, and procreation. He was also frequently connected with fertility. Though originally envisioned as an impersonal and supremely powerful cosmic force that personified sexual desire and procreation, Eros soon acquired a colorful mythology and personality of his own.[3]

Like the romantic love he embodied, Eros was full of contradictions. Early Greek poets wrote that he was sweet and warmed the heart,[4] yet he could also be cunning, unruly, and even cruel.[5] For the poet Sappho, Eros was perhaps the most powerful and irresistible of the gods;[6] Anacreon imagined him pursuing lovers with an axe or whip;[7] and many ancient sources even represented Eros as a kind of warrior.[8]

Eros flaunted the features of a beautiful young man or even a child. Hesiod referred to him as “fairest among the deathless gods;”[9] others went so far as to call him the youngest of the gods.[10] Eros was often described as winged, even golden-winged,[11] and was said to walk on flowers and wear a crown of roses—one of his symbols.[12] Sappho imagined a beautiful and youthful Eros flying through the air wearing a luxurious purple chlamys (a kind of cloak).[13]

Ever the childlike tempter, Eros loved playing games. Poets would represent him tossing around a ball[14] or competing with knucklebones, an early version of dice.[15] Of course, the crafty god of love was not above cheating.[16]

Together with figures such as Himeros (“Desire”), Pothos (“Longing”), and Anteros (“Reciprocated Love”), Eros was most often found in the entourage of Aphrodite, the goddess of love (who was sometimes called his mother). Some authors imagined more than one Eros, multiplying the mischievous god into a plurality of “Erotes.”[17]

Symbols

In addition to the flowers and roses whose scent constantly accompanied him, Eros’ symbols and attributes included his famous bow and arrows, with which he could produce not only love but also (according to some authors) the opposite of love—revulsion.[18] He also was said to carry the key to the apartments of Aphrodite,[19] flaming torches,[20] and nets in which to ensnare the victims of love.[21]

In later literature, as Eros’ power continued to expand, the god also began to take on the attributes of other gods: the thyrsus and tambourine of Dionysus, the lightning bolt of Zeus, the shield and helmet of Ares, the quiver of Apollo, the trident of Poseidon, the club of Heracles, and so on.[22]

Iconography

In the earliest Greek art, Eros was usually depicted as a winged young man—almost a boy—though he was sometimes portrayed as wingless as well. He appears both alone and with Aphrodite, carrying a lyre, a hare, or his famous bow and arrows. In early art, before Eros’ bow and arrows became ubiquitous, he was sometimes shown wielding a whip or a goad.

During the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE), however, Eros’ iconography began to shift: he was increasingly represented as a chubby infant, virtually inseparable from Aphrodite. This infantile Eros went on to influence depictions of the Roman Cupid and eventually turned into the cherubic figure that was so popular in European art.[23]

Terracotta plate showing a youthful, winged Eros placing a wreath on an altar. Attributed to the Ascoli Satriano Painter (ca. 340–320 BCE). From Apulia in Italy.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore MDPublic DomainFamily

Family Tree

Parents

Mother

Consorts

Wife

- Psyche

Children

Daughter

- Hedone

Mythology

Origins

Eros’ origins are obscure and vary depending on the source. In Hesiod’s Theogony, he is a primordial god and one of the first beings to come into existence, but many later authors made him a son of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, or of some other god. Eros was thus either one of the oldest gods or one of the youngest.

Eros and the Loves of Gods and Mortals

Eros had almost no myths of his own, yet he was ubiquitous in the myths of other gods and mortals. As early as the Homeric poems, the irresistible power of eros played a key role in Greek mythology as the force pulling Paris to Helen, Zeus to Hera, and the suitors to Penelope (though Homer never actually personified the concept of eros as the god Eros).[43] For Hesiod, the poet of the Theogony, it was Eros who accompanied Aphrodite when she went up to Olympus to join the gods.[44]

Later poets saw Eros everywhere:

Love [Eros], the unconquered in battle, Love, you who descend upon riches, and watch the night through on a girl's soft cheek, you roam over the sea and among the homes of men in the wilds. Neither can any immortal escape you, nor any man whose life lasts for a day. He who has known you is driven to madness.[45]

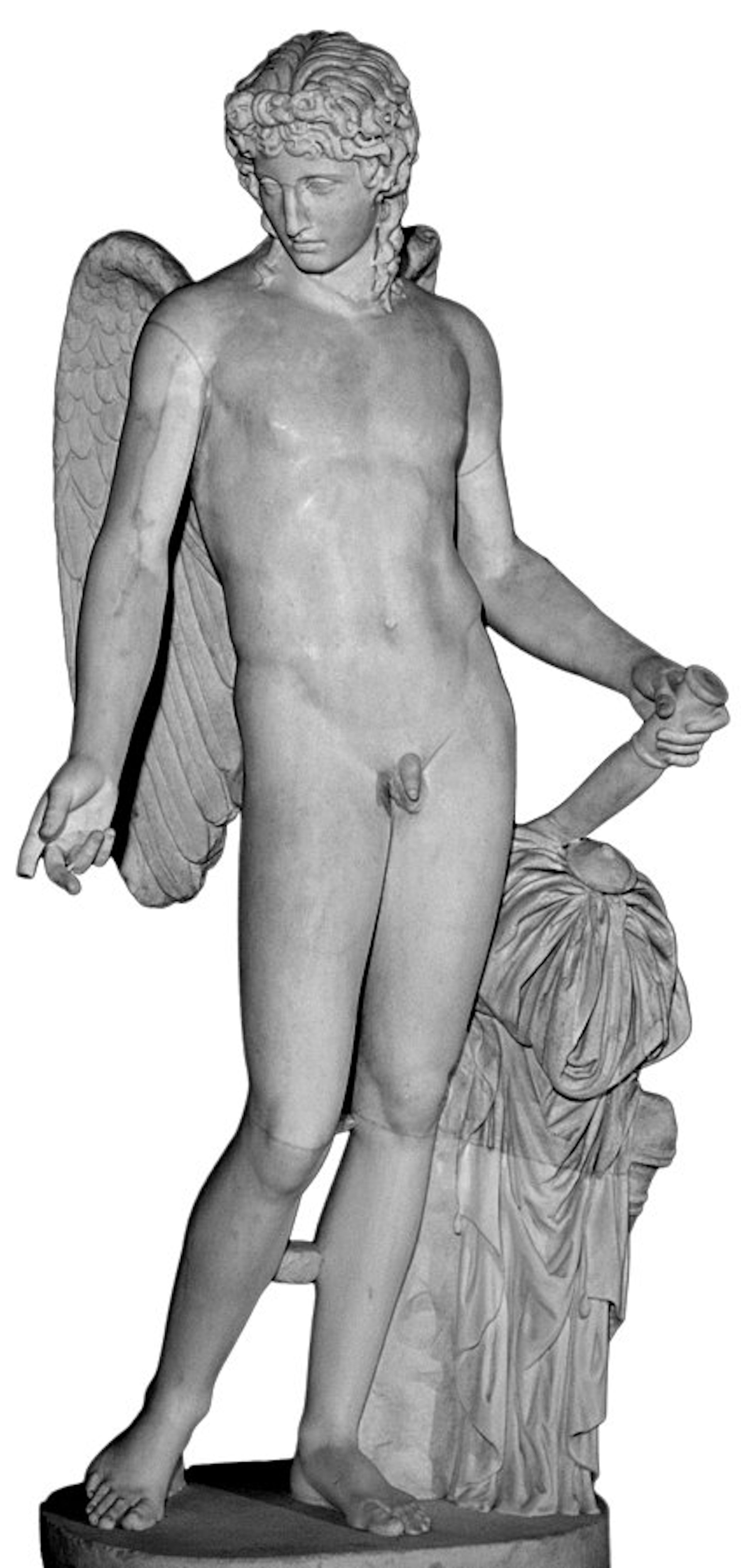

The so-called "Farnese Eros," Roman copy of fourth-century BCE Greek original by Praxiteles. National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy.

HaiducPublic DomainAny Greek myth that involved love or lust became, in a sense, a myth about Eros. It was Eros who, at the behest of his mother Aphrodite, caused Hades to fall in love with Persephone;[46] when Apollo mocked Eros’ weapons, Eros taught him a lesson by causing him to fall in love with the nymph Daphne while at the same time causing Daphne to be repulsed by him;[47] Aphrodite fell in love with the mortal Adonis when she grazed her finger on one of Eros’ golden arrows;[48] and all of Zeus’ loves—from Io to Olympias—were, of course, Eros’ doing.[49]

But Eros wreaked havoc upon mortals as well as gods.[50] In his Argonautica, Apollonius of Rhodes describes in detail how Hera wanted to help Jason get the Golden Fleece from the Colchian king Aeetes; thus, she had Aphrodite send Eros to make Aeetes’ daughter Medea fall in love with Jason.[51] Eros’ arrival and effects are colorfully described as follows:

Eros passed unseen through the grey mist, causing confusion... And quickly beneath the lintel in the porch he strung his bow and took from the quiver an arrow unshot before, messenger of pain. And with swift feet unmarked he passed the threshold and keenly glanced around; and gliding close by Aeson’s son [Jason] he laid the arrow-notch on the cord in the centre, and drawing wide apart with both hands he shot at Medea; and speechless amazement seized her soul. But the god himself flashed back again from the high-roofed hall, laughing loud; and the bolt burnt deep down in the maiden’s heart like a flame; and ever she kept darting bright glances straight up at Aeson’s son, and within her breast her heart panted fast through anguish, all remembrance left her, and her soul melted with the sweet pain. And as a poor woman heaps dry twigs round a blazing brand—a daughter of toil, whose task is the spinning of wool, that she may kindle a blaze at night beneath her roof, when she has waked very early—and the flame waxing wondrous great from the small brand consumes all the twigs together; so, coiling round her heart, burnt secretly Love the destroyer; and the hue of her soft cheeks went and came, now pale, now red, in her soul’s distraction.[52]

Eros and Psyche

Perhaps the most famous myth about Eros is narrated in only one source, and a late one at that—a late second-century CE novel by the Roman author Apuleius, commonly known today as the Golden Ass (its correct title is actually the Metamorphoses).[53]

The story tells of the princess Psyche (meaning “soul” in Greek), whose beauty had earned her the jealousy of Aphrodite.[54] In her envy, Aphrodite sent her son Eros[55] to cause Psyche to fall in love with a hideous monster.

But when Eros glimpsed Psyche, he fell in love with her himself. Disobeying his mother, he carried Psyche off to a hidden palace, where he became her lover. But though Eros visited Psyche every night, he did not tell her who he was and forbade her from seeing his face.

For a time, Eros and Psyche were happy together. But Psyche’s envious sisters started looking for ways to sow discord in the new relationship. At their urging, Psyche finally gazed at Eros’ face and discovered who he was. Eros subsequently abandoned Psyche, hurt by what he viewed as a violation of trust.

Psyche wandered the world for some time, seeking her divine lover. Aphrodite, who had discovered Psyche’s relationship with her son, tormented her viciously. But in the end, Psyche was reunited with Eros, won his (and Aphrodite’s) forgiveness, married him, and became a goddess.

Psyche Revived by the Kiss of Love by Antonio Canova (1793). Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainWorship

Temples

Eros was worshipped throughout the Greek world, though his cult never achieved the religious importance of many other gods.[56] His statue was commonly erected in gymnasia (public exercise complexes), alongside the herms of the god Hermes.

Eros’ most prominent cult center may have been Thespiae, in the central Greek region of Boeotia. His cult statue there, which was aniconic (that is, a symbolic representation rather than a literal one), was said to have been very ancient.[57] The cult of Eros was also important in other parts of Boeotia, such as Thebes, where the god was worshipped in connection with the Sacred Band (an elite military unit made up of 150 pairs of male lovers).[58]

Eros also had an important cult center in Athens. The remains of a temple he shared with Aphrodite have been discovered on the slopes of the Acropolis. He was also said to have had an altar in Athens that was first erected by the lover of the sixth-century BCE tyrant Hippias.[59] Altars of Eros (such as the one in the Academy of Athens and the gymnasium of Elis) were sometimes grouped together with altars of Anteros.[60]

Eros was also worshipped at other sites, including Leuctra in Laconia, where he had a shrine with a sacred grove;[61] Parium in northwestern Anatolia;[62] and Elea in southern Italy, where excavations have uncovered a temple to Eros.

Festivals

Eros was honored with festivals at several sites, including Thespiae and Athens. At Thespiae, his festival was called the Erotidia and included artistic as well as athletic contests.[63] At Athens, his festival was celebrated in the spring.

There were also various rituals and festivals of Eros connected with gymnasia throughout the Greek world, where the god was especially revered.[64] The Spartans and Cretans were known to offer sacrifices to Eros before battle.

Pop Culture

Eros is best known in modern pop culture through the figure of Cupid, his Roman equivalent. He continues to be represented as a young boy, usually an infant or toddler, with a bow and arrows (which, in more cartoonish representations, are complete with heart-shaped tips). He also appears in adaptations of Greek mythology, such as the TV shows Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess (where he is played by Karl Urban).