Uranus

Uranus and the Dance of the Stars by Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1834).

Architectural Museum of the Technical University of Berlin Public DomainOverview

A primordial deity in Greek mythology, Uranus personified the sky, the heavens, and the air. He was usually said to have been the first offspring of Gaia, herself the first deity and the personification of Mother Earth. Uranus and Gaia were the complementary halves of a primordial partnership that created the cosmos as the Greeks knew it.

Uranus fathered the Titans, the Cyclopes, and the monstrous Hecatoncheires. His rule over the heavens ended, however, when his son Cronus overthrew him at the dawn of time.

Unlike the Olympian deities, Uranus was never directly worshipped by the Greeks; he was a distant, inscrutable being, ultimately more a force of nature than a defined personality.

Etymology

The name “Uranus” (Greek Οὐρανός, translit. Ouranós) is also the ancient Greek word meaning “sky” or “heaven.” It is usually thought to have been derived from the Indo-European root *ṷérs-, meaning “to rain.” Uranus’ name would thus translate as “the rainmaker.”[1]

An alternative linguistic etymology links the Indo-European root of Uranus’ name (*ṷérs-) to the word for “height,” similar to the Sanskrit várṣman (“height, top”) or Lithuanian viršùs (“upper, highest seat”). In this case, Uranus’ name would mean “he who stands on high.”[2] However, this etymology is not generally accepted today.

Uranus’ name was generally Latinized by the Romans as Uranus; however, Roman authors sometimes referred to the sky god by other synonymous names, including Caelus and Aether.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Uranus Οὐρανός (Ouranós) Phonetic

IPA

[YOOR-uh-nuhs, yoo-REY-] /ˈyʊər ə nəs, yʊˈreɪ-/

Attributes

Functions and Characteristics

Uranus was essentially the sky and heavens imagined as an independent being. His highly metaphorical existence made him something akin to a force or essence—the male half of a duality that, together with Gaia, formed all things. Uranus came to embody the creative and generative power of the sky, which provided the earth—that is, Gaia—with warmth and humidity.[3]

Uranus (identified here with Aeon) stands over Gaia and their Titan children, from a floor mosaic in the Villa Sentinum in central Italy (early third century CE).

Bibi St. PolCC0Iconography

Because Uranus was almost never imagined in anthropomorphic terms, he was also never represented in ancient Greek art. The Romans eventually assimilated Uranus into other deities such as the Italian sky god Caelus and Aeon, the god of time. When Uranus was depicted as one of these gods, he was shown as a powerfully built male, usually bare-chested, sometimes young and beardless. He would occasionally be straddling a zodiac. In Roman art, Uranus was most often depicted on reliefs and marble sarcophagi.[4]

Family

Family Tree

Parents

Mother

Consorts

Wife

Children

Daughters

Sons

Mythology

Origins

Greek mythology, like many other world mythologies, begins with the separation of sky and earth. The familiar myth of Uranus and Gaia thus culminates, in Hesiod’s Theogony, with the castration of the sky-god Uranus and his forceful removal from the dominion of the earth-goddess Gaia. The overthrow of Uranus by his son Cronus forms the first part of the cycle of conflicts and successions of divine rulers often known as the “Succession Myth.”

There are numerous parallels with the myth of Uranus in Near Eastern mythology, but perhaps the closest and most revealing of these comes from the Hurro-Hittite world. In the Hurro-Hittite cosmogony, the sky god Anu (the counterpart of the Greek Uranus) rules the cosmos after Alalu. Anu is finally overthrown by his cupbearer Kumarbi (the counterpart of the Greek Cronus), who bites off his genitals. Kumarbi then devours his own offspring, but one of them, the storm god Teshub (the counterpart of the Greek Zeus) gets away and eventually overthrows him in turn.

This Near Eastern myth, which originated with the Hurrian people of Syria and Anatolia, was soon adopted by the powerful Hittites of Anatolia, from where it apparently spread west to the Greek world. In Hesiod, Anu becomes Uranus, who is castrated by Cronus much as Anu was castrated by Kumarbi; finally, Cronus is unseated by Zeus just as the Hurro-Hittite Kumarbi had been unseated by Teshub.

Other Near Eastern models may have also helped mold the myth of Uranus. In Egyptian mythology, for instance, the creation of the world begins when the couple Geb (earth) and Nut (sky) are separated from their tight embrace. And in the Mesopotamian Enūma Eliš, the primordial couple of Apsȗ (Fresh Water) and Tiamat (Sea Water) resemble the Greek primordial couple Uranus and Gaia.

The Rise and Fall of Uranus

Written around 800 BCE, Hesiod’s Theogony detailed the cosmogony, or creation of the world, as told by the ancient Greeks. According to the poet’s account, Uranus was Gaia’s first creation. Gaia created him, as Hesiod writes, “equal to herself, to cover her on every side, and to be an ever-sure abiding-place for the blessed gods.”[18]

Though he had many children with Gaia, Uranus was a cruel and unloving father. Ever suspicious, he soon grew paranoid that his children might try to usurp his privileged position. In an attempt to prevent this catastrophe, he consigned them to Tartarus, a pit of suffering located deep within the earth.[19]

Despairing at the fate of her children, Gaia formed a great sickle from flint stone and urged Titans (who in some accounts had been allowed to remain free) to castrate and overthrow Uranus. According to Hesiod, Cronus was the only one of Gaia’s children brave enough to commit the deed:

Then the son from his ambush stretched forth his left hand and in his right took the great long sickle with jagged teeth, and swiftly lopped off his own father's members and cast them away to fall behind him.[20]

In other traditions, however, it took all the Titans to overpower Uranus, with only Oceanus shirking from the deed.[21]

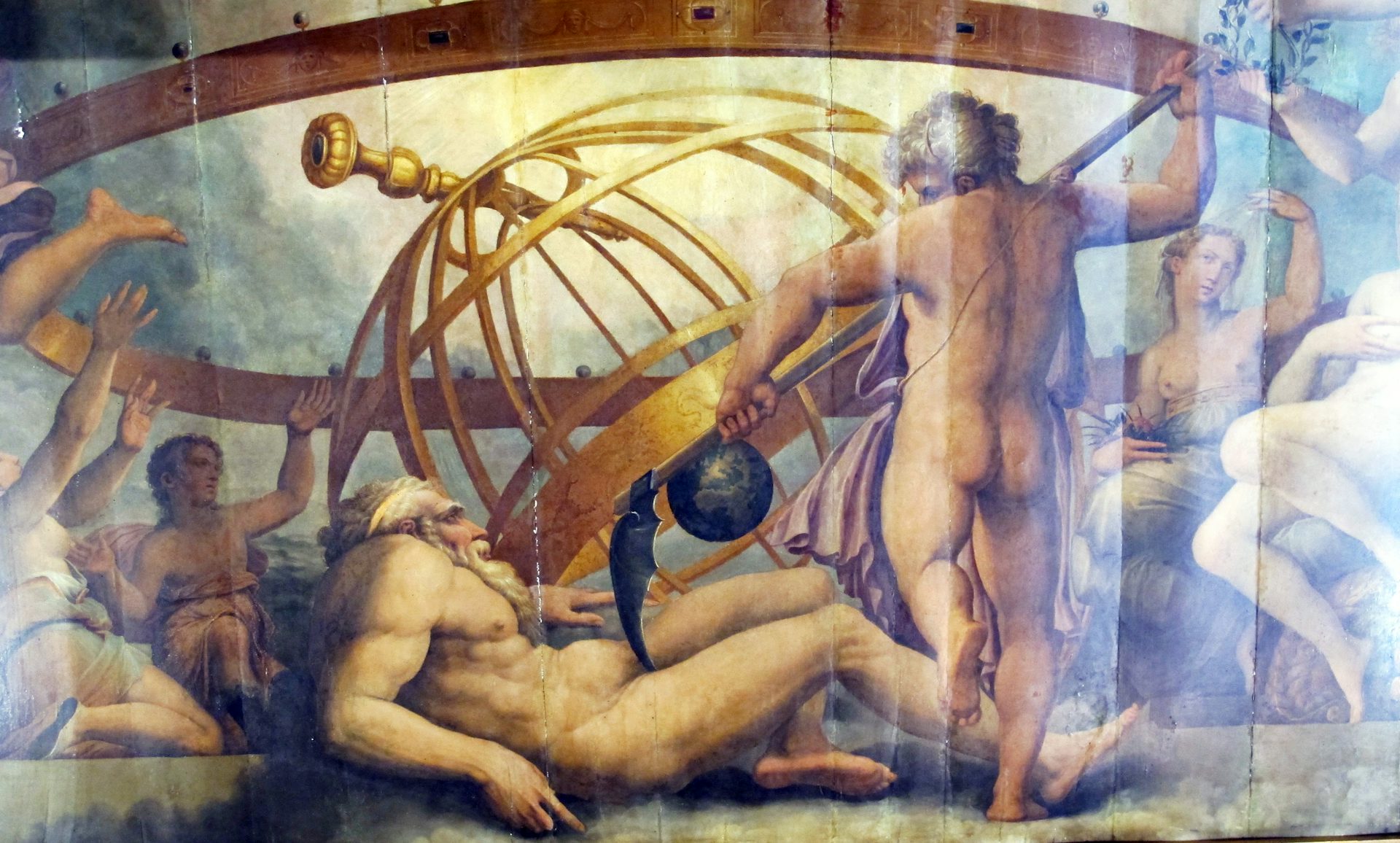

Detail of The Mutilation of Uranus by Saturn by Giorgio Vasari and Cristofano Gherardi (ca. 1540s–1550s), now in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Italy.

SailkoCC BY 3.0Uranus’ castration resulted in the birth of entire races of creatures: from the blood that fell upon the earth there emerged the Erinyes, the Giants, and the Meliae, while from the foam that bubbled from Uranus’ genitals—cast by Cronus into the sea—rose the beautiful Aphrodite.[22]

Uranus, unmanned, raged viciously against his children. According to Hesiod, he hailed them as the “Titans,” from the Greek verb meaning “to strain,” “for he said that they strained and did presumptuously a fearful deed, and that vengeance for it would come afterwards.”[23]

After he was overthrown, Uranus faded into the background and Cronus rose to power. But Uranus’ grim prophecy was fulfilled, for Cronus soon showed himself to be no less savage and wicked than his father. In time, Cronus fell prey to the same malicious suspicions that had plagued his father, and he too tried to rid himself of his children. But Cronus, rather than imprisoning his children in Tartarus, went a step further and swallowed them whole as soon as his wife Rhea had borne them to him. In the end, Rhea—with the help of Gaia and Uranus too—managed to conceal her last child, Zeus, from Cronus.[24] Zeus, of course, went on to overthrow Cronus and become the king of the gods, bringing to an end the violent cycle of divine succession.

Other Versions

Though Hesiod’s account of Uranus’ role in the cosmogony was widely accepted in antiquity, it was by no means the only version. The Orphics, an ancient sect with practices and mythological texts that differed from those of more mainstream Greek religion, usually seem to have envisioned creation beginning with a World Egg, sometimes said to have been fashioned from Chronos, “Time” personified. Uranus was among the deities who emerged from this egg, or was perhaps created by Phanes, the creator-god who emerged from the egg.[25] Or, alternatively, the Orphics made Nyx (“Night”) into the first being of the cosmos and the mother of Uranus and Gaia.[26]

Other ancient authors sought to rationalize the myth of Uranus. According to an account recorded by Diodorus of Sicily, Uranus was an early king of the lost city of Atlantis. When he died, his subjects lavished divine honors upon him, and even turned his name into the word for “sky.”[27]

Worship

Uranus was not worshiped as part of an organized cult, and did not even have any visual or figurative iconography. He was, however, sometimes invoked in oaths.[28] In his Roman guise of Caelus, Uranus may have taken on some more importance, for we encounter Roman invocations of Caelus aeternus (“eternal Caelus”),[29] and the Roman writer Vitruvius even noted in his treatise on architecture that temples of Caelus should be unroofed.[30]

Pop Culture

Today, Uranus lives on as the moniker of the seventh planet from the sun. Discovered in 1781 by William Herschel, the planet was originally called Georgium Sidus, or “George’s Star,” in reference to King George III, Herschel’s sovereign. The planet was renamed in the nineteenth century to universal acclaim.

“Uranus” was more in line with planetary names already in use, which also bore the names of Greco-Roman gods. It also followed a logical progression: Jupiter (Zeus), the fifth planet, was sired by Saturn (Cronus), the sixth planet, who was sired by Uranus (Caelus in Latin), the seventh and final planet (or so they thought at the time). Thus, the order of the planets in relation to Earth mirrored the succession of deities in Greek and Roman mythology.