Satyrs and Silens

Drunken Silenus supported by Satyrs attributed to Anthony van Dyck (ca. 1620).

The National Gallery, LondonPublic DomainOverview

Satyrs and silens (the two terms were often used interchangeably) were male hybrid creatures—mostly human, but with the ears, tail, and sometimes hind legs of a horse. They were easily identified by their snub noses and large erect penises. Known above all for their love of wine, music, and sex, the satyrs were frequently imagined pursuing nymphs through the forest. Appropriately, these creatures were close companions of Dionysus, the god of wine and intoxication.

Satyrs and silens were much more popular in the visual arts than in literature. However, a few of these creatures—such as Silenus and Marsyas—had myths of their own. Satyrs also inspired the “satyr play,” a genre of burlesque-style mythological plays featuring choruses of satyrs. Satyrs and silens were occasionally honored in cult, primarily in connection with Dionysus.

Etymology

The etymologies of the terms “satyr” (Greek σάτυρος, translit. sátyros) and “silen” (Greek σειληνός, translit. seilēnós) are obscure.

“Satyr” may come from the Greek word σάτυρος (sátyros), which combines the root *saro-, meaning “the female sex,” with the root *turo-, meaning “to grasp, take hold of.” A satyr would thus be “he who grasps females” (a reference to one of the creatures’ favorite pastimes).[1] Others have tried to derive the term from the words σαίνω (saínō, “swell”), ψῆν (psên, “touch, rub”), and τυ-ρο-ς (ty-ro-s, “grasp”).

Alternatively, it may be an Illyrian loanword going back to the Indo-European root *seh₁- (“sow”) or *seh₂- (“satiate”).[2] Another possibility is that the term “satyr” came from the Near East, either from the Semitic root str (“destroy”)[3] or from the Egyptian snṯr (“to make holy”).[4]

The etymology of the term “silen” is even more uncertain. It may have come from a Thracian word meaning “wine”[5]—a reference to the silens’ connection with Dionysus, the god of wine.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

satyr, satyrs σάτυρος, σάτυροι (translit. sátyros, sátyroi) Phonetic

IPA

[SEY-ter], [SEY-terz] /ˈseɪ tər/, /ˈseɪ tərz/

English

Greek

silen, silens σειληνός, σειληνοί (translit. seilēnós, seilēnoí) Phonetic

IPA

[SAHY-len], [SAHY-lenz] /ˈsaɪ lɛn/, /ˈsaɪ lɛnz/

Attributes

Appearance and Abilities

Satyrs and silens were hybrid creatures, half-human and half-beast. Along with the Maenads, they belonged to the entourage (or thiasos) of Dionysus, the Olympian god of wine and intoxication. They were usually regarded as woodland creatures (similar to Maenads, nymphs, and Centaurs).

Nymphs and Satyr by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1873).

Sterling and Francine Clark Art InstitutePublic DomainSatyrs and silens were typically imagined with the ears, tail, and occasionally legs and coat of a horse (or goat). They tended to be bald or balding, with a snub nose, and were usually depicted naked so as to display a large erect penis (satyrs and silens were always male). It is possible that they were immortal, though a few myths describe them dying or being killed.[6]

It is unclear what the distinction was between satyrs and silens, or if a meaningful distinction even existed.

Satyrs and silens were rarely mentioned in the earliest Greek literature. The few descriptions we have portray them as wild and lustful: in the fifth Homeric Hymn, for example (the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite), the silens make love to the nymphs who live in the mountains.[7] They were thus similar to the half-horse Centaurs, also described as insatiably lustful creatures. Unlike the Centaurs, however, satyrs and silens were not particularly violent or dangerous—rather, they were usually seen as amusing, fun-loving, and even a bit cowardly.

Satyrs and silens became more popular around the middle of the fifth century BCE, with the emergence of the “satyr play.” These plays, like tragedies, usually dramatized a mythological story, but with a chorus of satyrs who turned the whole affair into a kind of burlesque.

In a satyr play, the chorus of satyrs is led by their father, Silenus (or Papposilenus), suggesting that satyrs and silens were largely interchangeable. Some later writers, likely influenced by this depiction of Silenus, wrote that the oldest of the satyrs were called silens, or that the satyrs were the offspring of the older silens.[8]

Iconography

Most of what we know about how satyrs and silens were imagined in antiquity comes from the visual arts. These creatures became important subjects for artists around the early sixth century BCE. Though they were almost always represented with the ears and tail of a horse, other details of their appearance changed over time. For example, they were originally shown with either horse legs or human legs, but by the end of the sixth century BCE the human-legged type had become more common.

It is possible that the horse-legged type were silens, while the human-legged ones were satyrs. But as time went on, the two races became interchangeable. Silenus himself—the silens’ mythical namesake—was often represented as human-legged.[9] After 450 BCE, it became more and more common to show them with goat features—including a goat’s tail, ears, hind legs, and sometimes even horns—instead of horse features. This made them similar in appearance to Pan.

From the sixth century BCE onwards, satyrs and silens were commonly shown participating in the Dionysian revel (the komos)—drinking wine, playing the flute, dancing, and performing acrobatics—or pursuing nymphs or Maenads. Occasionally, they were depicted collecting grapes and making wine. Their attributes (wineskins, flutes) complemented these activities.

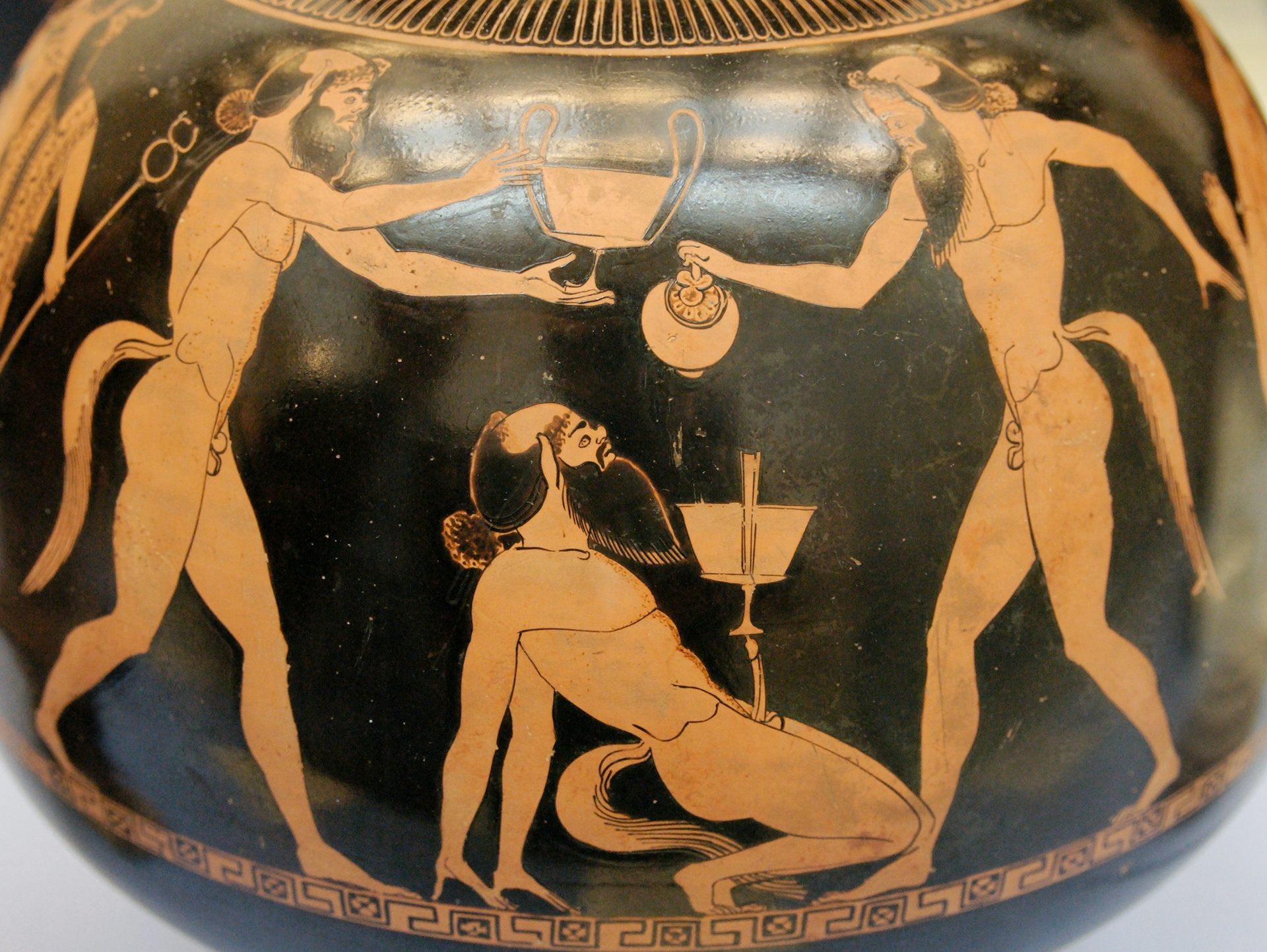

Attic red-figure psykter (wine cooler) showing satyrs or silens engaged in a highly acrobatic komos (revel). Signed by Douris (ca. 500–490 BCE). British Museum, London, UK.

Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainOriginally, satyrs and silens were only represented in connection with a few mythical tales (mainly Hephaestus’ return to Olympus and the Gigantomachy). But in the fifth century BCE, as the satyr play became more popular, their role expanded; they appeared in a greater variety of scenes, especially those involving Heracles.

The Romans inherited the satyrs and silens from the Greeks. Sculptures of these creatures were very popular in Roman villas and gardens, where they symbolized luxury and leisure. Satyrs and silens also frequented Roman reliefs, punch bowls, and sarcophagi. Occasionally—though not as often as one might expect—the Romans equated satyrs and silens with the fauns of Italian mythology.[10]

Family

The earliest literary source to mention satyrs—a fragment of the (Pseudo-)Hesiodic Catalogue of Women—traced the ancestry of these strange creatures to Dorus and Phoroneus, two of the earliest mythological inhabitants of Greece. According to this text, the satyrs were siblings of the mountain nymphs and of the rustic gods known as the Curetes.[11]

But because much of the fragment’s text is missing, we can only guess at the exact identities of the satyrs’ parents. A possible reconstruction suggests that the satyrs (or at least some of them) were children of Dorus’ daughter Iphthime and the god Hermes.[12] It is also possible that in other sources (maybe even in the Catalogue of Women), this Iphthime had several sisters who slept with other gods to give birth to the other satyrs.[13]

Whether the silens had different origins or were the same as the satyrs is unclear. Athenian satyr plays, which featured a chorus of satyrs led by their father Silenus, seem to have popularized the idea that the satyrs were the children of an older satyr (or silen) named Silenus.[14] Some later sources, probably trying to make sense of the confusing and inconsistent traditions that had been handed down to them, said that the oldest satyrs were called silens, or else that the silens were the fathers of the satyrs.[15]

The parentage of some individual satyrs or silens, however, was completely different, suggesting that these creatures came into being in many ways.

For example, depending on the source, Silenus was either the son of an unnamed nymph,[16] of Hermes,[17] or of Pan and an unnamed nymph;[18] or he was born from the earth, either spontaneously[19] or when it was inseminated by the blood of the castrated Uranus.[20]

Another satyr, Marsyas, was said to have been the son of either Hyagnis,[21] Olympus,[22] or the Thracian king Oeagrus,[23] while another source specified that his mother was a nymph.[24]

Mythology

Origins

Satyrs and silens entered the Greek imagination relatively late, around the end of the seventh century BCE or the beginning of the sixth century BCE.

There are similarities between the satyrs and silens of the Greeks and creatures from other Indo-European mythologies, such as various kinds of elves and goblins; for instance, we might compare the satyrs and silens to the Celtic Drusii, goblins who also had a penchant for seducing women. It is possible that all of these creatures shared a common Indo-European origin.[25]

Similar creatures, such as the Semitic goat-demons sometimes known in Hebrew as Se’īrīm, also seem to have existed in the ancient Near East.[26]

The Satyrs and Silens with their God

In literature as in art, satyrs and silens were often found in the company of Dionysus and played an important role in his wild band of revelers (the thiasos).

Satyrs and silens often accompanied Dionysus on his adventures. For example, Nonnus’ Dionysiaca, a long epic poem composed around the fifth century CE, tells of how Dionysus fought a war against the Indians with an army made up largely of satyrs and silens.[27]

In many traditions, Dionysus was raised with or by the satyrs and silens. Silenus, the oldest and wisest of these creatures, was the tutor of the young Dionysus. In one myth, the Phrygian king Midas longed for Silenus’ wisdom and captured him (perhaps by lacing Silenus’ fountain with wine). But Silenus’ hard-won advice was remarkably pessimistic: he told Midas that the best thing for mortals was not to be born at all, while the second best was to die as soon as possible.[28]

Marble statue of Silenus holding the infant Dionysus. Roman copy (mid-second century CE) after early Hellenistic original, perhaps by the school of the sculptor Lysippus (ca. 300 BCE). Vatican Museums, Vatican, Italy.

JastrowPublic DomainIn another story, Dionysus’ first love was the handsome satyr Ampelus. But Ampelus died tragically (either by falling from a great height or by being gored by a bull). From his blood, however, there emerged the first vine. The heartbroken Dionysus named the new creation after his beloved Ampelus. Soon after, he invented wine by plucking the grapes from the vine and using them to make a fermented liquid.[29]

One myth claimed that the satyrs and silens came to help Dionysus when Olympus was attacked by the brutal Giants. As they rode in on their donkeys, the satyrs and silens inadvertently won the war for the gods: the Giants were so terrified when they heard the braying of the donkeys that they immediately ran away.[30]

The Hubris of the Satyrs and the Silens

Sometimes, the wild and unrestrained nature of the satyrs and silens got them into trouble. The gods, who were not especially forgiving even on their best days, did not hesitate to punish or kill satyrs and silens who upset them.

In one myth, the Danaid Amymone was in the woods looking for water when she accidentally disturbed a sleeping satyr. The satyr sprang up and tried to have sex with her. Amymone fled, with the satyr in hot pursuit. But Poseidon showed up, drove the satyr away, and then slept with Amymone himself.[31]

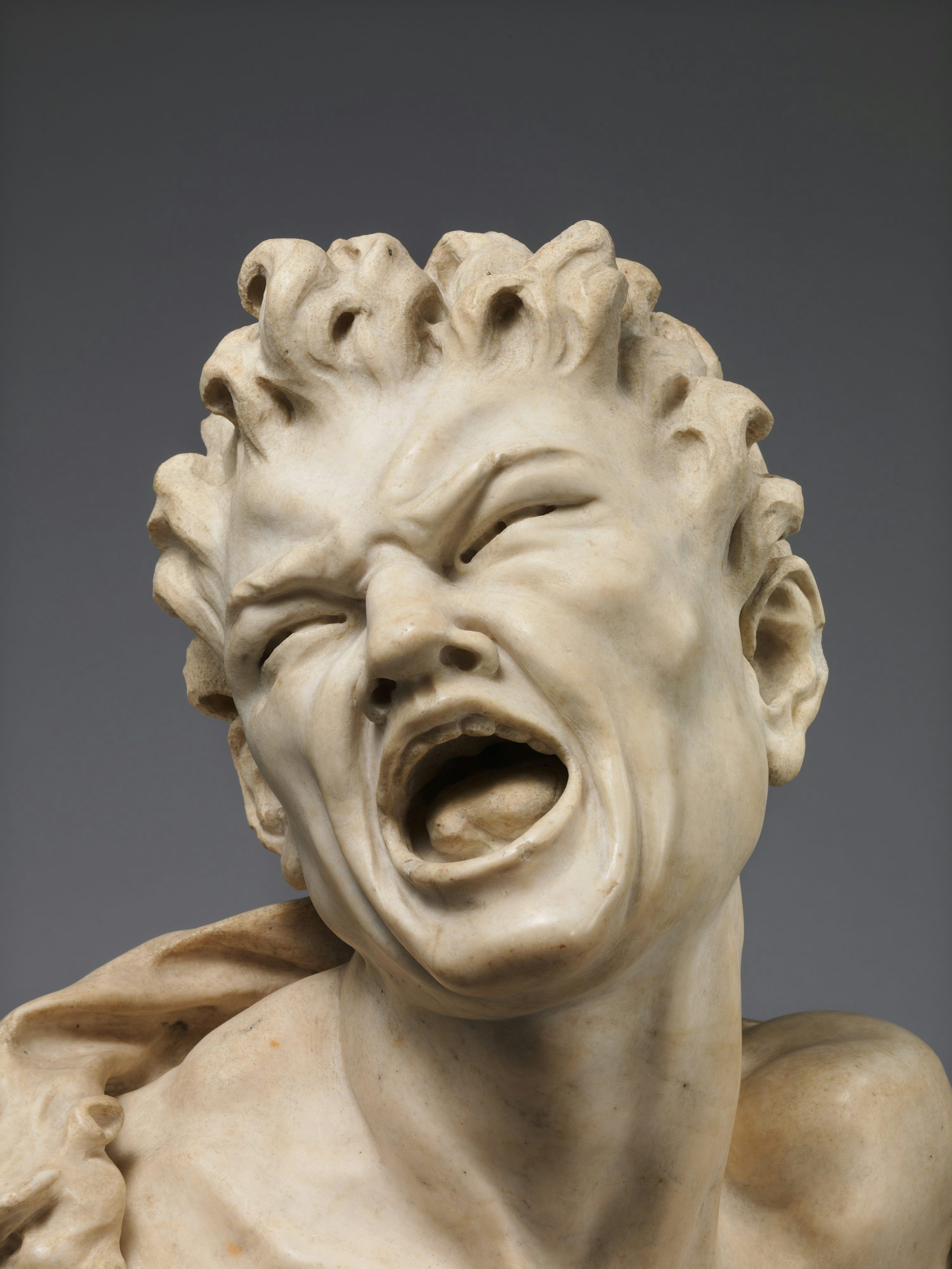

One famous myth told of how another satyr, Marsyas, brought about his own destruction when he challenged Apollo to a music contest. Marsyas had discovered panpipes when the instrument was invented and subsequently discarded by Athena. He quickly became a virtuoso and was certain that his instrument was superior to all others—even the lyre of Apollo.

Before their contest, Marsyas and Apollo agreed that whoever won could do what he wanted with the other. At first, Marsyas proved an even match for the great Apollo. But Apollo decided to play his lyre upside down and challenged Marsyas to do the same. Marsyas, of course, could not complete the task, and Apollo was judged the winner.

Apollo punished Marsyas cruelly for his hubris in challenging a god: he tied him to a tree and flayed him alive. Ovid renders Marsyas’ suffering in all its gory detail:

Even as he shrieked out in his agony,

his living skin was ripped off from his limbs,

till his whole body was a flaming wound,

with nerves and veins and viscera exposed.

But all the weeping people of that land,

and all the Fauns and Sylvan Deities,

and all the satyrs, and Olympus, his

loved pupil—even then renowned in song,

and all the Nymphs, lamented his sad fate;

and all the shepherds, roaming on the hills,

lamented as they tended fleecy flocks.[32]

The tears shed by Marsyas’ friends created the River Marsyas, a tributary of the Meander in Phrygia.[33]

Marsyas by Balthasar Permoser (1680–1685).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWorship

Satyrs and silens were worshipped in some parts of Greece, generally in connection with the more important Olympian god Dionysus. Since the creatures were part of Dionysus’ band of mythical revelers, it was only natural to worship them together with their leader.

Athens was probably the most important cult center of the satyrs and silens. At festivals like the Dionysia and Lenaea, the Athenians honored Dionysus with ceremonies and plays, including tragedies, comedies, and satyr plays. The chorus of “satyrs” in these satyr plays would dress up very distinctively in a snub-nosed satyr mask, a fur leotard, and a loin cloth sporting a tail and a large erect phallus (called a perizoma).

Sometimes it was not only the actors who dressed up in satyr costumes, but spectators as well. This practice is attested in Athens (especially at the Anthesteria festival),[34] as well as in Alexandria[35] and Rome.[36] It remained a popular pastime as late as the seventh century CE, when it was banned by the Christian government in Constantinople.[37]

Satyrs and silens were also seemingly connected with the Mysteries of Dionysus.[38] Combined with their appearance on funerary art, this suggests that they had a religious connection with the afterlife.

Finally, Silenus—the revered tutor of Dionysus—was sometimes worshipped independently. As with other satyrs, his cult was especially prominent in Attica.[39] But he was honored in other parts of the Greek world as well, including Malea[40] and Elis.[41]

Pop Culture

Satyrs can be found in modern film, television, literature, and games, including Dungeons and Dragons and Magic: The Gathering. They are especially prevalent in the fantasy genre.

Today, satyrs are also increasingly conflated with fauns, hybrid creatures from Roman mythology with the horns, ears, and hind legs of a goat (rather than a horse). This is how the satyr Grover Underwood is depicted in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series.

The satyrs’ insatiable sexual appetite is sometimes excluded from modern representations of them. However, this important attribute has not been entirely forgotten: “satyriasis” is a common (though clinically controversial) term for male hypersexuality (the popular term for female hypersexuality, also inspired by Greek mythology, is “nymphomania”).