Homeric Hymns

Attic red-figure amphora showing a young man singing and playing the cithara by the Berlin Painter (ca. 490 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

The Homeric Hymns are made up of thirty-three poems,[1] each of which celebrates an individual god or group of gods. In antiquity, the hymns were attributed to Homer, the same poet who was said to have written the Iliad and the Odyssey. Today, however, the Homeric Hymns are thought to have been composed primarily between the seventh and fifth centuries BCE—after the Iliad and the Odyssey—and are probably the work of many different authors.

The Homeric Hymns vary widely in length and content. The longer hymns contain a narrative element, while the shorter ones are usually no more than an invocation of the god or gods being addressed in the hymn.

These hymns are an important example of early Greek sacred poetry and were frequently performed at festivals and musical events. They influenced many later poets, though today they are not nearly as famous as other works of early Greek literature, such as the Homeric epics, the Hesiodic epics, and Attic tragedy.

Title

The Homeric Hymns, as the name suggests, are an early example of what the Greeks called “hymns” (Greek ὕμνοι, translit. hýmnoi; sing. “hymn,” Greek ὕμνος, translit. hýmnos). A term of obscure origins, the word “hymn” could refer to any song in ancient Greece, but by the Classical period (ca. 490–323 BCE) it was mostly used for a particular type of song written in honor of a god.

In early sources, the Homeric Hymns were also described as προοίμια (prooímia), “preludes,” because they were originally sung as introductions to longer poems.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Homeric Hymns ὕμνοι (translit. hýmnoi)/ὕμνοι Ὁμηρικοί (translit. hýmnoi Homērikoí) or προοίμια (translit. prooímia) Phonetic

IPA

[hoh-MER-ik himz] /hoʊˈmɛr ɪk hɪmz/

Author(s)

The ancient Greeks usually attributed the Homeric Hymns to Homer, the mysterious poet also said to have authored the Iliad and the Odyssey.[2] This attribution, however, was doubted even in antiquity, and today it is universally rejected—not only because most scholars no longer believe that a single poet named “Homer” ever existed, but also because the Homeric Hymns emerged primarily between the seventh and fifth centuries BCE, some time after the Iliad and the Odyssey (written in the eighth century BCE).

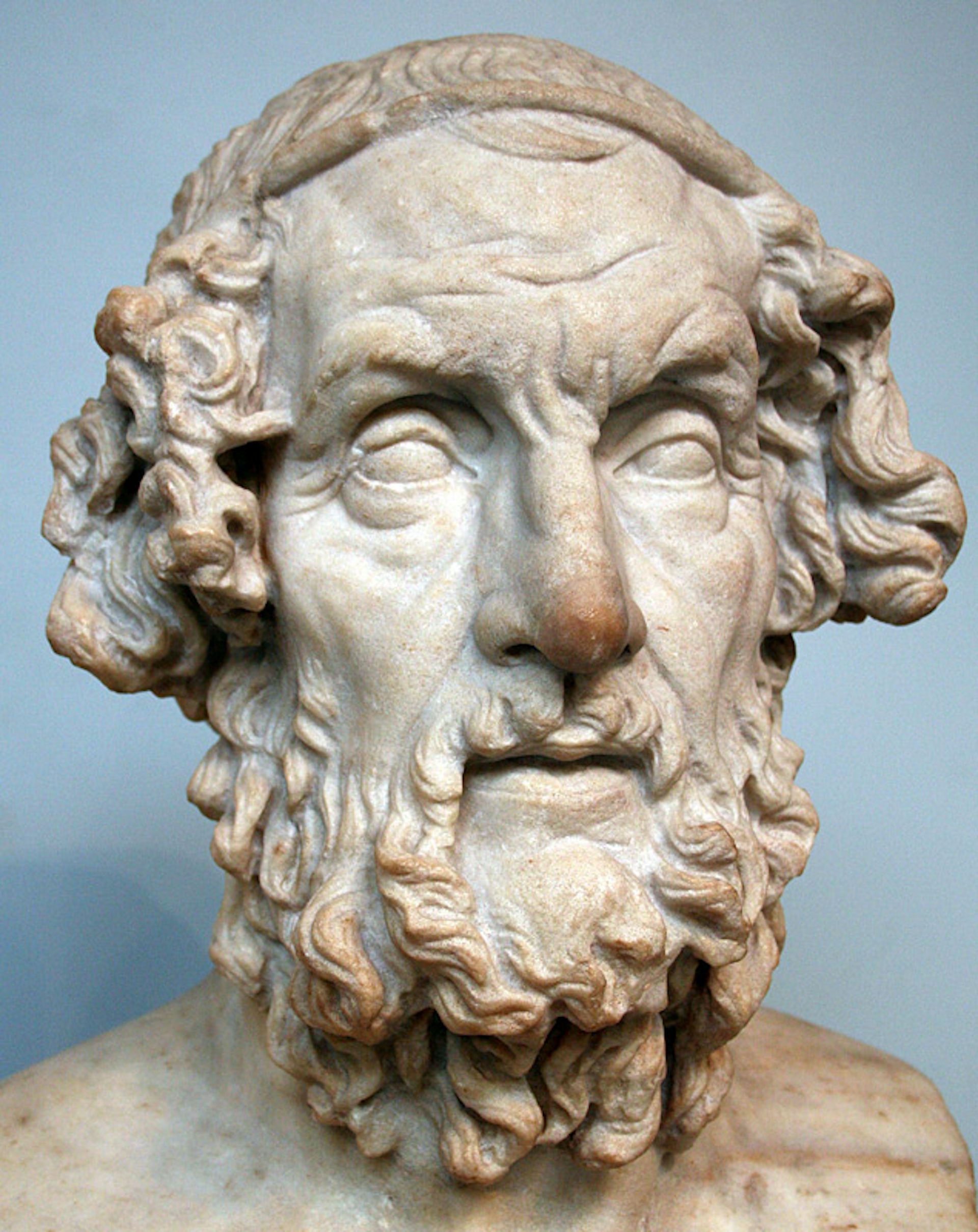

Bust of Homer. Roman copy of Hellenistic Greek original from the 2nd century BCE. From Baiae, Italy.

British MuseumPublic DomainScholars have concluded that the Homeric Hymns were composed by a variety of poets, most of them living before 400 BCE. Some of the hymns may have been written by members of the Homeridae, a clan of professional poets from the island of Chios who claimed to be descendants of Homer.[3] Cynaethus, for example, a member of the Homeridae who lived in the sixth century BCE, was likely the author of the third Homeric Hymn (to Apollo).

Mythological Context

Each of the thirty-three poems usually counted among the Homeric Hymns is addressed to a god or group of gods (though there is a thirty-fourth hymn addressed simply to “hosts”). Typically the gods celebrated in these hymns are Olympians—the most important gods of Greek religion and myth, who ruled the cosmos from atop Mount Olympus.

The Olympians came to power when Zeus and his siblings overthrew their father Cronus, a tyrannical Titan who had swallowed his own children. Zeus then established a new cosmic order, with himself at the head. The Twelve Olympians—the major deities of the Greek pantheon—consisted of Zeus, his siblings, and a few of his children.

The most famous Homeric Hymns describe the origins of the new Olympian gods and their domains of power. The second hymn, for example, explains how Demeter became goddess of the harvest and seasons; the third hymn details how Apollo became god of prophecy, beauty, and art; the fourth hymn narrates how the mischievous Hermes became god of messengers and thieves; and so on.

Other, shorter hymns are little more than invocations hailing one Olympian god or another, listing some of their attributes and (literally) singing their praises. Some of the gods celebrated in the hymns—such as Heracles (in Homeric Hymn 15) and the Dioscuri (in Homeric Hymns 17 and 33)—were not included among the official Twelve Olympians, but they were still sometimes said to live on Mount Olympus.

The Homeric Hymns offer important information on early Greek religious practices. Indeed, some of the earliest references to religious rituals and sites are scattered throughout these poems.

Synopsis

The Homeric Hymns are a collection of thirty-three poems, varying in length from only a few lines to over 500 lines of dactylic hexameter verse. A thirty-fourth hymn is sometimes included in the collection, though it is addressed not to a god but rather to all hosts, reminding them of the sanctity of hospitality.

The contents of the Homeric Hymns are summarized below.

Homeric Hymn 1 (to Dionysus)

The first Homeric Hymn is fragmentary. Only about 21 lines of the poem survive, describing the birth of Dionysus—the god of wine—in Nysa.

Homeric Hymn 2 (to Demeter)

The second Homeric Hymn (495 lines) tells of the abduction of Demeter’s daughter Persephone by Hades, ruler of the Underworld. Having spied Persephone picking flowers, Hades is overcome with love and carries her away to be his bride. Demeter searches desperately for her daughter, and when she cannot find her, she forsakes her divine duties as the goddess of agriculture, no longer making the crops ripen. Eventually, Demeter and Hades come to an arrangement in which Persephone spends part of the year with her mother and part of the year with her new husband.

The poem describes the origins of the changing seasons, with the productive summer months representing Demeter’s yearly reunion with Persephone, and the frosty winter months representing the period when the goddess mourns her daughter’s absence. In another section of the hymn, Demeter teaches agriculture and religious rites to the people of Eleusis; this is considered the founding myth of the Eleusinian Mysteries, an important religious cult centered near Athens.

Photo showing a view of the excavation of Eleusis, Greece. This is the site of the annual Eleusinian Mysteries and an early temple to Demeter and Persephone, built around the 7th century BCE.

Marcus CyronCC BY-SA 2.0Homeric Hymn 3 (to Apollo)

The third Homeric Hymn (546 lines) is made up of two distinct sections, and may have originally been two separate poems. The first part describes Apollo’s birth on the island of Delos, which subsequently became the site of one of his most sacred shrines. The second part recounts his triumphant arrival in Delphi after slaying the serpent that had terrorized the area (nameless in the hymn but known in later sources as “Python”).

This hymn, like the second Homeric Hymn, can be understood as a “foundation myth”—or rather, as two foundation myths (for Apollo’s sanctuary in Delos as well as his sanctuary in Delphi). We are also given a glimpse of Apollo’s arrival on Mount Olympus as he rises to become one of the most important gods of the Greek pantheon:

Leto’s all-glorious son goes to rocky Pytho, playing upon his hollow lyre, clad in divine, perfumed garments; and his lyre, at the touch of the golden key, sings sweet. Thence, swift as thought, he speeds from earth to Olympus, to the house of Zeus, to join the gathering of the other gods: then straightway the undying gods think only of the lyre and song, and all the Muses together, voice sweetly answering voice, hymn the unending gifts the gods enjoy and the sufferings of men, all that they endure at the hands of the deathless gods, and how they live witless and helpless and cannot find healing for death or defence against old age. Meanwhile the rich-tressed Graces and cheerful Seasons dance with Harmonia and Hebe and Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus, holding each other by the wrist. And among them sings one, not mean nor puny, but tall to look upon and enviable in mien, Artemis who delights in arrows, sister of Apollo. Among them sport Ares and the keen-eyed Slayer of Argus, while Apollo plays his lyre stepping high and featly and a radiance shines around him, the gleaming of his feet and close-woven vest. And they, even gold-tressed Leto and wise Zeus, rejoice in their great hearts as they watch their dear son playing among the undying gods.[4]

Homeric Hymn 4 (to Hermes)

The fourth Homeric Hymn—the longest of them, at 580 lines—tells of Hermes’ birth and childhood, culminating in his invention of the lyre and his theft of his older brother Apollo’s cattle. Full of crafty escapades and racy humor, the poem puts Hermes’ defining attributes on full display.

Homeric Hymn 5 (to Aphrodite)

The fifth Homeric Hymn (293 lines) tells of how Zeus finally subordinated Aphrodite to him. As the goddess of sexuality, Aphrodite had long plagued the other gods with the torments and heartaches of love, but the time had come for her to experience those same hardships:

But upon Aphrodite herself Zeus cast sweet desire to be joined in love with a mortal man, to the end that, very soon, not even she should be innocent of a mortal’s love; lest laughter-loving Aphrodite should one day softly smile and say mockingly among all the gods that she had joined the gods in love with mortal women who bare sons of death to the deathless gods, and had mated the goddesses with mortal men.[5]

In this hymn, Zeus causes Aphrodite to fall in love with Anchises, a mortal prince of Troy. The two begin an affair that results in the birth of a son, whom Aphrodite tellingly names Aeneas, “terrible grief.”

Homeric Hymn 6 (to Aphrodite)

Homeric Hymn 6 is another hymn to Aphrodite—though at 21 lines, it is much shorter than the previous one. The poem invokes Aphrodite traveling in her divine entourage.

Homeric Hymn 7 (to Dionysus)

The seventh Homeric Hymn (59 lines) tells the myth of the pirates who tried to kidnap the handsome Dionysus, not realizing he was a god. Dionysus punishes their folly by twining their ship in grapevines and turning the impious pirates into dolphins.

The Dionysus Cup by Exekias (ca. 530 BCE), showing Dionysus sailing in a ship with dolphins

MatthiasKabelCC BY-SA 3.0Homeric Hymn 8 (to Ares)

The eighth Homeric Hymn (17 lines) is a brief invocation of Ares as the powerful and dreaded god of war.

Homeric Hymn 9 (to Artemis)

The ninth Homeric Hymn (9 lines) is a brief invocation of Artemis as the archer goddess of the wild and the sister of Apollo.

Homeric Hymn 10 (to Aphrodite)

Homeric Hymn 10 (6 lines) is a brief invocation of Aphrodite as the goddess of joy and pleasure.

Homeric Hymn 11 (to Athena)

The eleventh Homeric Hymn (5 lines) addresses Athena as the goddess of war and the female counterpart of Ares.

Homeric Hymn 12 (to Hera)

The twelfth Homeric Hymn (5 lines) invokes Hera as the glorious queen of the gods.

Homeric Hymn 13 (to Demeter)

At just three lines long, the thirteenth Homeric Hymn is the shortest of the hymns. It contains only the introduction and conclusion to a hymn in honor of Demeter.

Homeric Hymn 14 (to the Mother of the Gods)

The fourteenth Homeric Hymn (6 lines) invokes a goddess addressed simply as the “mother of the gods.” The poem mentions the cymbals and lions associated with the mother goddess Cybele, who was usually identified with Rhea, mother of Zeus.

Homeric Hymn 15 (to Heracles)

The fifteenth Homeric Hymn (9 lines) is addressed to “Heracles the lion-hearted,” the mortal son of Zeus and Alcmene who accomplished many heroic deeds in life and became a god after his death.

Homeric Hymn 16 (to Asclepius)

The sixteenth Homeric Hymn (5 lines), like the thirteenth, is an abbreviated hymn, with just the introduction and conclusion of a song to Asclepius, the god of healing.

Statue of Asclepius with his snake-entwined staff by Alessandro and Francesco Sanguinetti (1848–1859)

New Palace, Potsdam / SteffenheilfortCC BY-SA 3.0Homeric Hymn 17 (to the Dioscuri)

Homeric Hymn 17 (5 lines) is a brief invocation of the Dioscuri, sons of Zeus and the mortal Leda who, like Heracles, became gods after their death.

Homeric Hymn 18 (to Hermes)

The eighteenth Homeric Hymn (12 lines) is a much shorter version of the fourth hymn, also addressed to Hermes.

Homeric Hymn 19 (to Pan)

The nineteenth Homeric Hymn (49 lines) addresses Pan, a goat-footed and fun-loving woodland god. The poem dwells on Pan’s attributes and activities.

Homeric Hymn 20 (to Hephaestus)

The twentieth Homeric Hymn (8 lines) invokes Hephaestus as the god of craftsmanship and smithing.

Homeric Hymn 21 (to Apollo)

Homeric Hymn 21 (5 lines) is a very brief invocation of Apollo.

Homeric Hymn 22 (to Poseidon)

Homeric Hymn 22 (7 lines) is a short poem addressed to Poseidon, the god of the sea.

Homeric Hymn 23 (to Zeus)

The twenty-third Homeric Hymn (4 lines) invokes Zeus himself as “chiefest among the gods and greatest, all-seeing, the lord of all, the fulfiller who whispers words of wisdom to Themis as she sits leaning towards him.”[6]

Homeric Hymn 24 (to Hestia)

Homeric Hymn 24 (5 lines) is a brief hymn to Hestia, goddess of the hearth and home.

Homeric Hymn 25 (to the Muses and Apollo)

The twenty-fifth Homeric Hymn (7 lines) is addressed to the nine Muses and Apollo, all patron gods of the arts.

Homeric Hymn 26 (to Dionysus)

Homeric Hymn 26 (13 lines) is a brief invocation of Dionysus as the god of wine.

Homeric Hymn 27 (to Artemis)

The twenty-seventh Homeric Hymn (22 lines) is an invocation of Artemis—daughter of Zeus and Leto and twin sister of Apollo—as goddess of the wild.

Homeric Hymn 28 (to Athena)

The twenty-eighth Homeric Hymn (18 lines) addresses Athena as the goddess of craft and war. It briefly recounts the myth of Athena’s birth from Zeus’ head.

Minerva Born from the Head of Jupiter by René-Antoine Houasse (before 1688)

Palace of VersaillesPublic DomainHomeric Hymn 29 (to Hestia)

The twenty-ninth Homeric Hymn (13 lines) is addressed to Hestia as a goddess of the domestic sphere (in partnership with Hermes).

Homeric Hymn 30 (to Gaia)

Homeric Hymn 30 (19 lines) invokes Gaia, the primordial earth goddess, as mother of all.

Homeric Hymn 31 (to Helios)

The thirty-first Homeric Hymn (20 lines) is addressed to Helios, the Titan god of the sun and bringer of daylight.

Homeric Hymn 32 (to Selene)

The thirty-second Homeric Hymn (20 lines) is dedicated to Selene, Titan goddess of the moon.

Homeric Hymn 33 (to the Dioscuri)

Homeric Hymn 33 (19 lines) is a brief invocation of the Dioscuri (also invoked in Homeric Hymn 17).

Style and Composition

The Homeric Hymns exemplify many of the conventions of early Greek epic poetry, including dactylic hexameter and an elevated, artificial diction. They also vary widely in length: the second, third, fourth, and fifth hymns are all quite long and include extended narratives, while many other hymns are no more than a few lines.

The Homeric Hymns generally follow a tripartite structure, comprising: 1) an invocation of the god to whom the hymn is addressed; 2) a worship section, which in the longer hymns usually involves an extended narrative or myth about the god; and 3) a concluding prayer asking for the god’s favor.

The hymns were probably performed at formal events, such as festivals or music contests, though they may have also been sung at smaller private gatherings, like banquets. Originally, they likely served as introductions to longer poems (such as heroic epics), but some of the lengthier Homeric Hymns may have represented independent literary works in their own right.

We cannot know the exact dates of composition of the Homeric Hymns (now thought to be the work of many different poets). However, we can make some educated guesses based on stylistic and historical grounds.

The earliest Homeric Hymns, including the longer hymns, were almost certainly composed between the seventh and fifth centuries BCE. The second hymn, for instance, was likely written in honor of the construction of the Telesterion—the great sanctuary at Eleusis—in the early sixth century BCE, while the third hymn may have first been performed at a celebration held by Polycrates (the tyrant of Samos) in 522 BCE.

Apollo Killing Python by Hendrik Goltzius (1589)

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainOther hymns, on the other hand, are not as old. A few were probably composed during the Hellenistic period, between the fourth and second centuries BCE, and at least one hymn (Homeric Hymn 8, dedicated to Ares) appears to have been written as late as the fifth century CE.

Themes

The Homeric Hymns are religious poems, and religion is thus one of their central themes. The hymns, in many ways, represent the consolidation of early religious beliefs during the Archaic period (ca. 900–490 BCE)—the same period in which Homer and Hesiod were writing their epics. Collectively, the Homeric Hymns outline the origins, epithets, and powers of the twelve Olympian gods who dominated the Greek pantheon, along with a handful of other important gods (including Heracles, the Dioscuri, and Gaia).

The Homeric Hymns reveal much about how the ancient Greeks saw themselves in relation to their world. Within these poems, the gods are always supreme—though they are not necessarily all-powerful. Even Zeus, the ruler of the gods, has his limits; for instance, he can be subjugated by the power of love (the domain of the goddess Aphrodite). Despite these limitations, the gods are far more powerful than humans, who must honor the gods and obey them—or else suffer the consequences.

The Homeric Hymns are full of gods who interact with humans (for better or for worse), often in disguise.[7] These interactions allow the gods to display their awesome and awful power over mortals. But they also demonstrate that the gods can be as generous to the pious as they are terrible to those who incur their wrath.

Venus and Anchises by William Blake Richmond (1889–1890)

Walker Art Gallery, LiverpoolPublic DomainThe Homeric Hymns are also an example of performed poetry, and these performances were often competitive. Indeed, contests of every kind—athletic, artistic, and musical—were an important feature of Greek culture, and the hymns reflect that. The Homeric Hymns vied with other poems and traditions to establish the authoritative version of the gods and their respective mythologies. Consider the opening lines of the fragmentary first Homeric Hymn (the hymn to Dionysus):

For some say, at Dracanum; and some, on windy Icarus; and some, in Naxos, O Heaven-born, Insewn; and others by the deep-eddying river Alpheus that pregnant Semele bare you to Zeus the thunder-lover. And others yet, lord, say you were born in Thebes; but all these lie. The Father of men and gods gave you birth remote from men and secretly from white-armed Hera. There is a certain Nysa, a mountain most high and richly grown with woods, far off in Phoenice, near the streams of Aegyptus…[8]

Another signal of the hymns’ performative (and competitive) function is the formula found at the end of most of the poems—a formula that reflects both the uniqueness of each hymn as an individual poem as well as its place within a larger tradition: “And now I will remember you and another song also.”[9]

Reception

The Homeric Hymns were quite important in the ancient world. They defined and shaped the genre of Greek sacred poetry, which seems to have included many texts that no longer exist. Some of the semi-legendary names associated with the genre include Orpheus, Musaeus, Pamphus, and Olen. Later, the Hellenistic poet Callimachus drew on the Homeric Hymns in his own five hymns to the gods, as did the authors of the Orphic Hymns and the philosopher Proclus.

The Homeric Hymns continued to be read throughout late antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the modern period. But without the religious context of Greek ritual, they lost much of their meaning and did not enjoy the same popularity and prestige as other works of classical Greek and Roman literature.

Today, the Homeric Hymns are encountered relatively rarely, with the longer hymns (2, 3, 4, and 5) read more frequently than the many short ones. Some of the myths contained in the hymns—perhaps especially the myth of Demeter and Persephone in the second Homeric Hymn—are well known in their own right and continue to be adapted in contemporary literature, art, and pop culture.

Translations

There have been many English translations of the Homeric Hymns, especially in recent decades. The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful translations of the complete collection:

Evelyn-White, H. G., trans. and ed. Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914: A rather old-fashioned—though still useful—prose translation; contains facing Greek text.

Shelmerdine, Susan C., trans. The Homeric Hymns. 2nd ed. Newburyport, MA: Focus, 1995: An accurate free verse translation, with introduction and helpful notes.

Crudden, Michael, trans. The Homeric Hymns. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: Verse translation with introduction and notes.

Cashford, Jules, trans. The Homeric Hymns. London: Penguin, 2003: Free verse translation with useful introduction and notes by Nicholas J. Richardson.

West, Martin L., ed. and trans. The Homeric Hymns, Homeric Apocrypha, Lives of Homer. Loeb Classical Library 496. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003: Accurate prose translation with facing Greek text; contains brief notes.

Hine, Daryl, trans. Works of Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005: Readable, accurate, and annotated translation replicating the verse of the original (dactylic hexameter).

Ruden, Sarah, trans. The Homeric Hymns. Hackett Classics. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2005: Verse translation with introduction and brief notes.

Chapman, George, trans. Chapman’s Homeric Hymns and Other Homerica. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008: Popular verse translation from 1624; reprinted with a modern introduction by Stephen Scully.

Rayor, Diane J., trans. The Homeric Hymns. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014: Verse translation with introduction and notes (first published in 2004).

Athanassakis, Apostolos N., trans. The Homeric Hymns. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020: Highly literal translation in iambic verse, with introduction and notes (first published in 1976).