Uranian Cyclopes

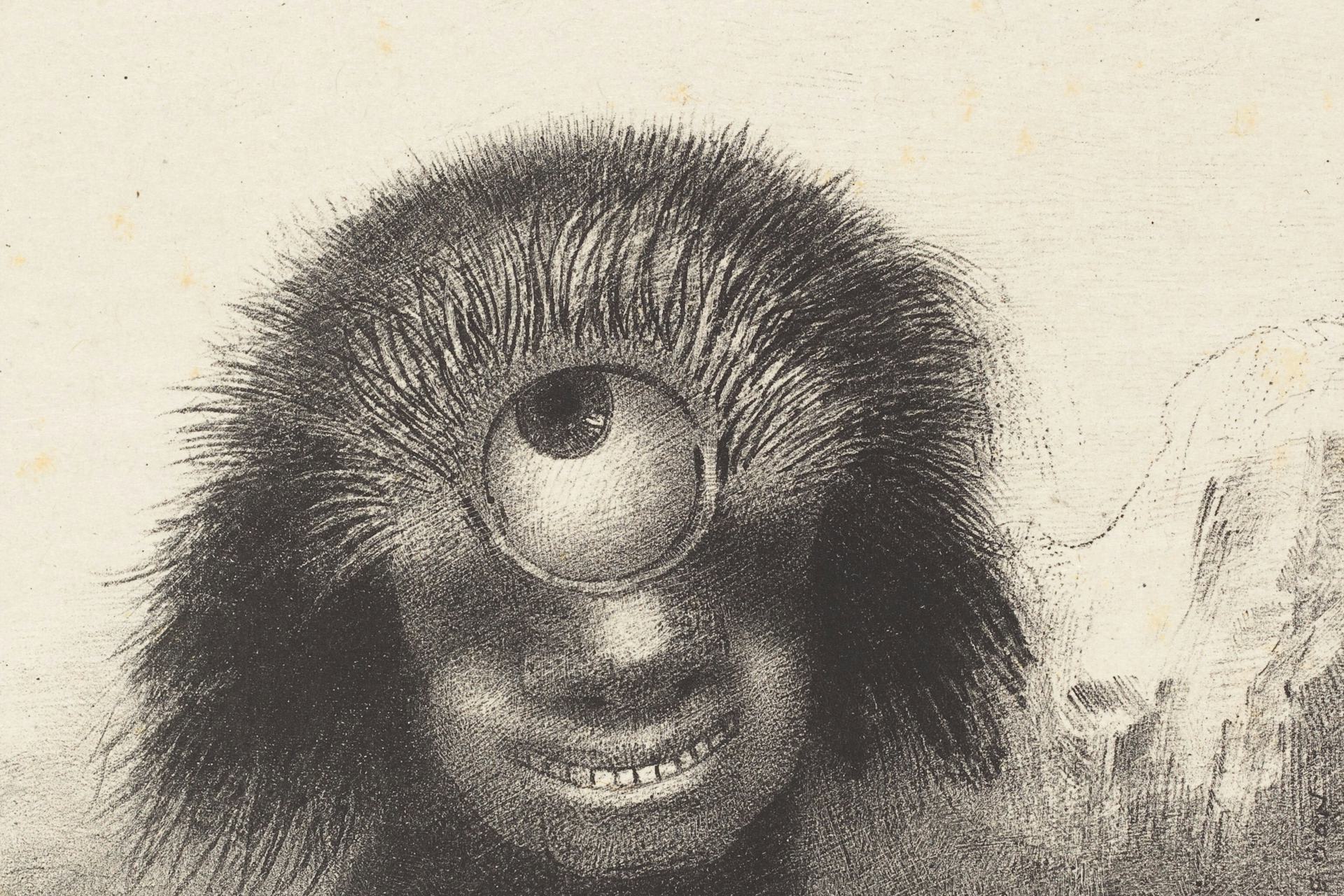

The deformed polyp floated on the shores, a sort of smiling and hideous Cyclops by Odilon Redon (1883)

National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., United States)Public DomainOverview

The Uranian Cyclopes, named Brontes, Steropes, and Arges, were sons of Gaia and Uranus. Like the rest of Uranus’ children, they were imprisoned beneath the earth for many years before being finally freed by the Olympians. After helping the Olympians defeat the Titans in the decade-long Titanomachy, the Cyclopes commanded a place of honor in the mythological cosmos.

The Uranian Cyclopes were highly skilled craftsmen. They fashioned weapons, armor, and ornaments for many heroes and gods, but their most famous creation by far was the thunderbolt of Zeus.

Etymology

The Uranian Cyclopes’ chief function was to make Zeus’ lightning bolts; unsurprisingly, then, each had a name corresponding to one aspect of lightning or thunder. The name “Brontes” comes from the Greek word brontē, meaning “thunder”; the name “Steropes” comes from the Greek word steropē, meaning “lightning bolt”; and the name “Arges” comes from the Greek word argē, meaning “flashing” (an adjective or epithet often applied to words for lightning).

Ancient sources named a handful of other, lesser-known Cyclopes: Acamas, an able craftsman;[1] Agriopus;[2] Aortes;[3] Elatrius, Euryalus, Halimedes, and Trachius, great warriors who helped the god Dionysus in his war against the Indians;[4] and Geraestus, whose tomb had religious significance.[5] It is unclear what relationship (if any) these Cyclopes had to Brontes, Steropes, and Arges, but they may have been sons of the original three Cyclopes.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Arges, Brontes, Steropes Ἄργης, Βρόντης, Στερόπης Phonetic

IPA

[AR-jeez], [BRON-teez], [sterr-OH-peez] /ˈɑːr dʒiːz/, /ˈbrɒn tiːz/, /ˌstɛrˈoʊ piːz/

Alternate Names

The names Acmonides,[6] Argilipus,[7] and Pyragmon[8] may have been alternate names for Arges, while the name Asteropaeus[9] may have been used for Steropes.

Titles and Epithets

The Uranian Cyclopes boasted few epithets, perhaps because their names were already epithet-like (as discussed above, Brontes, Steropes, and Arges all have names that are evocative of thunder and lightning).

Attributes and Iconography

Like all Cyclopes, Brontes, Steropes, and Arges each had one large eye in the middle of their forehead. As sons of Uranus, the three were often called the Uranian Cyclopes so as to distinguish them from other mythological Cyclopes (such as the brutish Polyphemus).[10]

A detailed description of Brontes, Steropes, and Arges can be found in Hesiod’s Theogony:

And again, [Gaia] bore the Cyclopes, overbearing in spirit, Brontes, and Steropes and stubborn-hearted Arges, who gave Zeus the thunder and made the thunderbolt: in all else they were like the gods, but one eye only was set in the midst of their foreheads. And they were surnamed Cyclopes (Orb-eyed) because one orbed eye was set in their foreheads. Strength and might and craft were in their works.[11]

In art, Brontes, Steropes, and Arges were depicted like other Cyclopes, as giant anthropomorphic creatures with a single eye. They were sometimes represented in Hephaestus’ workshop or fashioning Zeus’ lightning bolts, but they were not as popular a subject as the more ferocious Polyphemus, the Cyclops of the Odysseus myth.[12]

Family

Brontes, Steropes, and Arges were sons of the primordial deities Gaia and Uranus. This made them siblings of the Twelve Titans and the Hecatoncheires.

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

Seeking to secure his power against potential rivals, Uranus imprisoned the Cyclopes beneath the earth. There, they were joined by Uranus’ other offspring by Gaia: the Hecatoncheires (who had one hundred arms and fifty heads each) and the Titans. But Gaia pitied her children and helped them defeat Uranus: she gifted a scythe to Cronus, the youngest of the Titans, who used it to cut off Uranus’ genitals.

The Titanomachy

Following Uranus’ demise, Cronus and the other eleven Titans became the rulers of the cosmos, while the Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires remained in their underground prison. Eventually, they were freed by Zeus and the other Olympians during their war against Cronus and the Titans—the so-called Titanomachy. Endlessly grateful, the Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires were more than happy to help Zeus in his war.

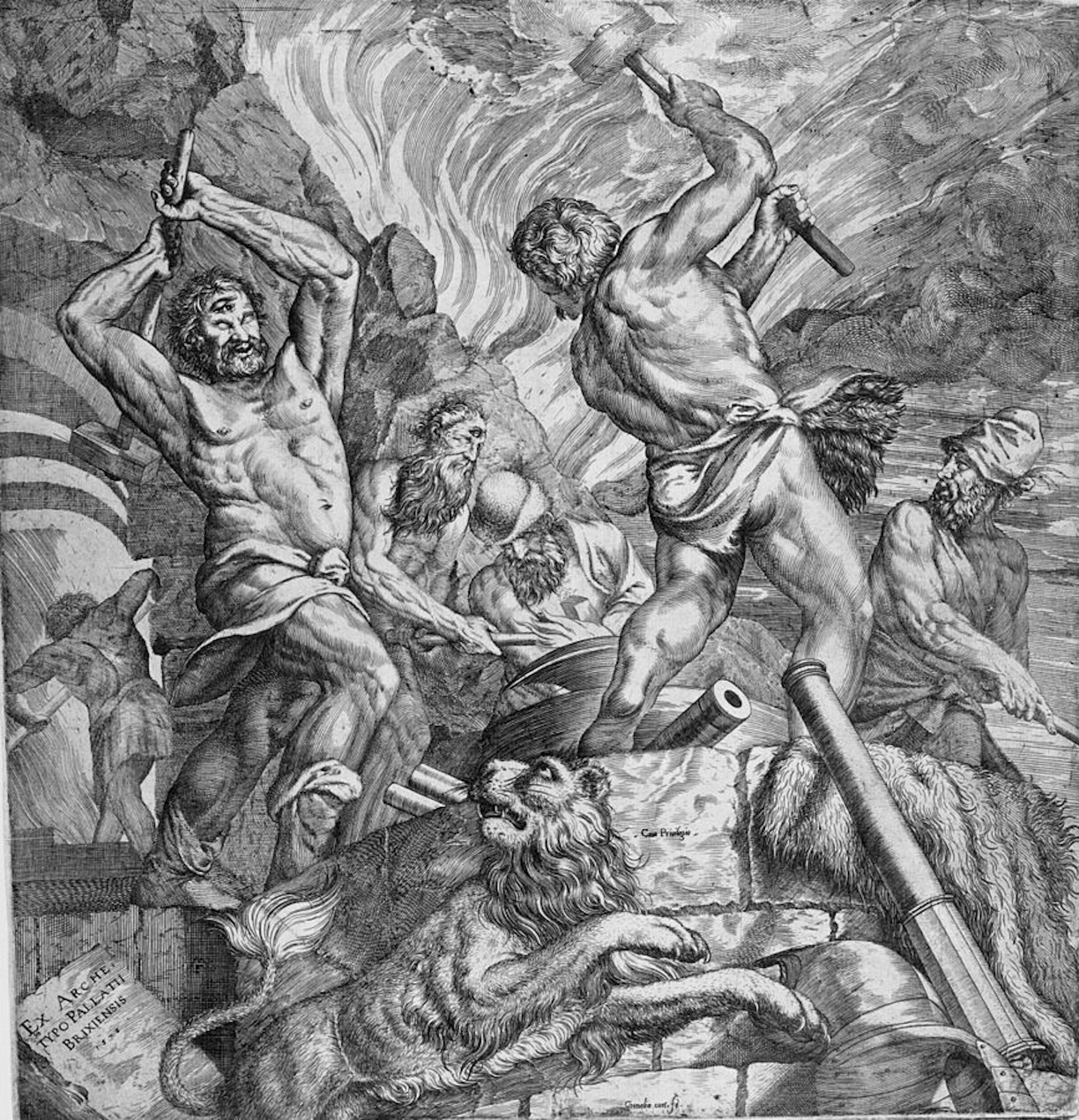

The Forge of the Cyclopes by Cornelis Cort (1572). Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainTheir entrance proved to be the turning point in the Titanomachy. While the Hecatoncheires used their hundred arms to bury the Titans under a barrage of stones, the Cyclopes made invincible weapons and armor for the Olympians. To Zeus they gave “the glowing thunderbolt and lightning”;[13] to Hades they gave a helmet (probably the helmet of invisibility, featured most famously in the myth of Perseus); and to Poseidon they gave his iconic trident.[14]

The Fate of the Uranian Cyclopes

After helping to defeat the Titans and establish the Olympians as rulers of the cosmos, the Uranian Cyclopes appear to have held a respected place in Greek mythology. They continued to fashion the lightning bolts of Zeus, and in some traditions, they helped the smith god Hephaestus in his workshop, producing armor, weapons, and ornaments for various gods and heroes.

There are different versions of what ultimately happened to the Cyclopes. In one well-known tradition, their fate was sealed after Zeus killed Apollo’s son Asclepius with a lightning bolt; in a rage, Apollo retaliated by killing the Cyclopes, who had made the weapon.[15]

However, this myth is difficult to reconcile with the supposed immortality of the Cyclopes. Perhaps to resolve this problem, some sources claimed that Apollo killed not the first three Uranian Cyclopes (Brontes, Steropes, and Arges, who were immortal), but their sons (who were mortal).[16] The names of these sons are not specified in any surviving ancient works.

There is yet another version of the fate of the Cyclopes in which Zeus is named as their killer; he hoped to prevent them from making lightning and thunder for anyone else.[17]

Pop Culture

Though the Cyclopes in general have been prominent in modern pop culture, there have been few modern adaptations of the three Uranian Cyclopes. They do make some appearances, however—for example, as characters in the video game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey and in the Canadian animated television series Class of the Titans.