Poseidon

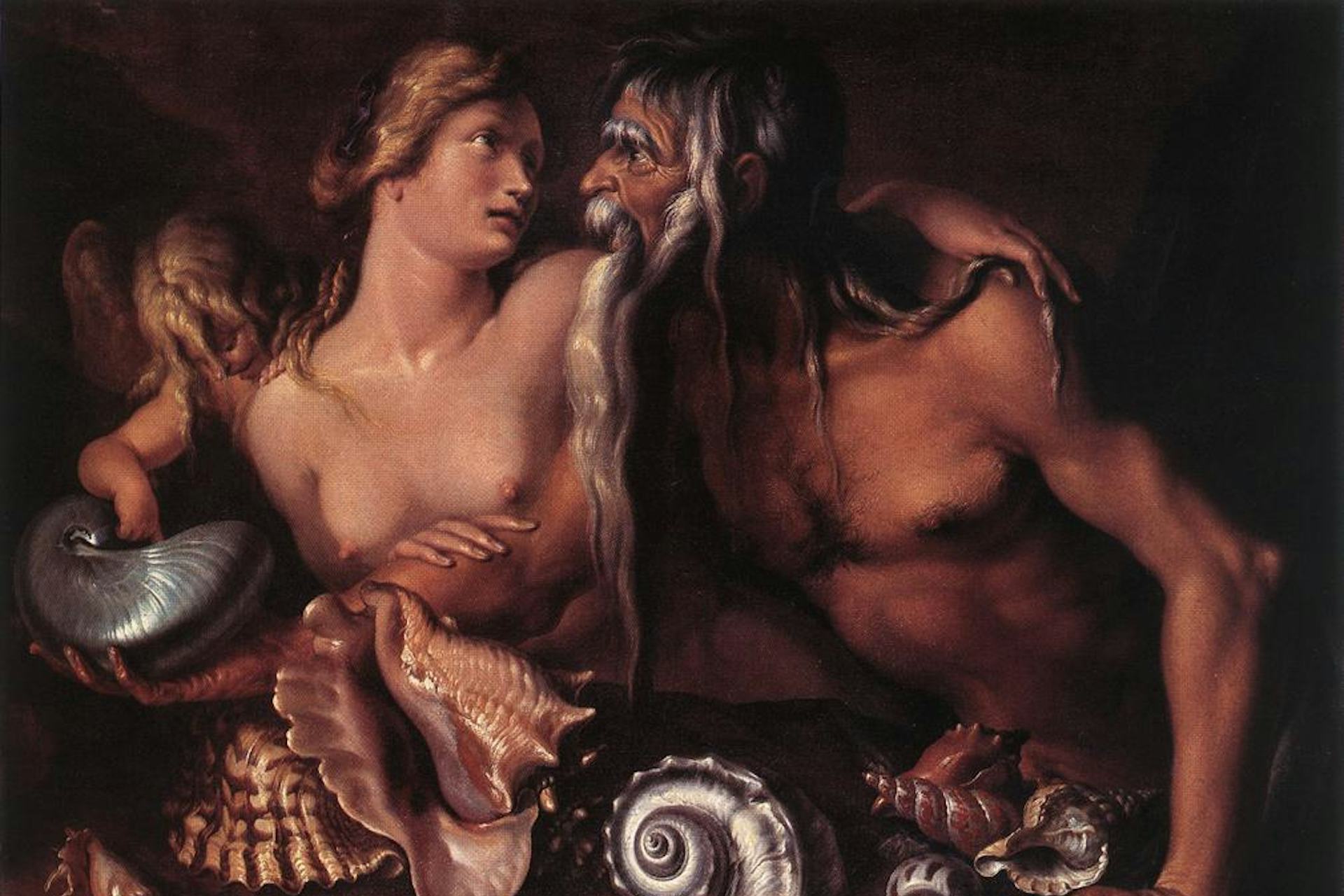

Neptune and Amphitrite by Jacob de Gheyn II (ca. 1610)

Wallraf-Richartz Museum, ColognePublic DomainOverview

Poseidon was a powerful Olympian and the Greek god of the seas, seafarers, earthquakes, and horses. Worshipped across the entirety of the Greek world, Poseidon had particularly strong followings in seafaring city-states, such as Athens and Corinth.

One of the chief Olympian deities, Poseidon was a defiant god whose power was second only to that of his brother Zeus. As such, he played a major role in many Greek myths. He was usually depicted riding his beautiful horses or wielding his menacing trident.

Key Facts

Who was Poseidon’s wife?

Poseidon was married to Amphitrite, a sea goddess who was typically named as one of the Nereids (the fifty daughters of Nereus and Doris). Their most famous child was Triton, a sea god often represented as a merman.

Neptune and Amphitrite by Jacob de Gheyn II (ca. 1610)

Wallraf-Richartz Museum, ColognePublic DomainWhere did Poseidon live?

As one of the Olympian gods, Poseidon had a home on Mount Olympus. However, he spent much of his time in the depths of the sea, where he was said to have several vast underwater palaces. In literature and art, Poseidon was usually represented riding over the waves in a chariot drawn by magnificent horses (who sometimes had fins in place of legs) and wielding his great trident.

Neptune Seated on a Marine Monster and Blowing a Conch Shell by Severo Calzetta da Ravenna (late 15th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHow was Poseidon worshipped?

Poseidon was worshipped by Greeks everywhere, though there were many local variations in his cult. The cult of Poseidon was especially important in Corinth; the Isthmian Games, which were celebrated near Corinth every other year, were dedicated to Poseidon.

Jason, Wearing Only One Sandal, Attending Pelias' Sacrifice to Poseidon by Leonard Thiry (16th century)

Leiden University LibraryCC BY 4.0Poseidon’s Grudge Against Odysseus

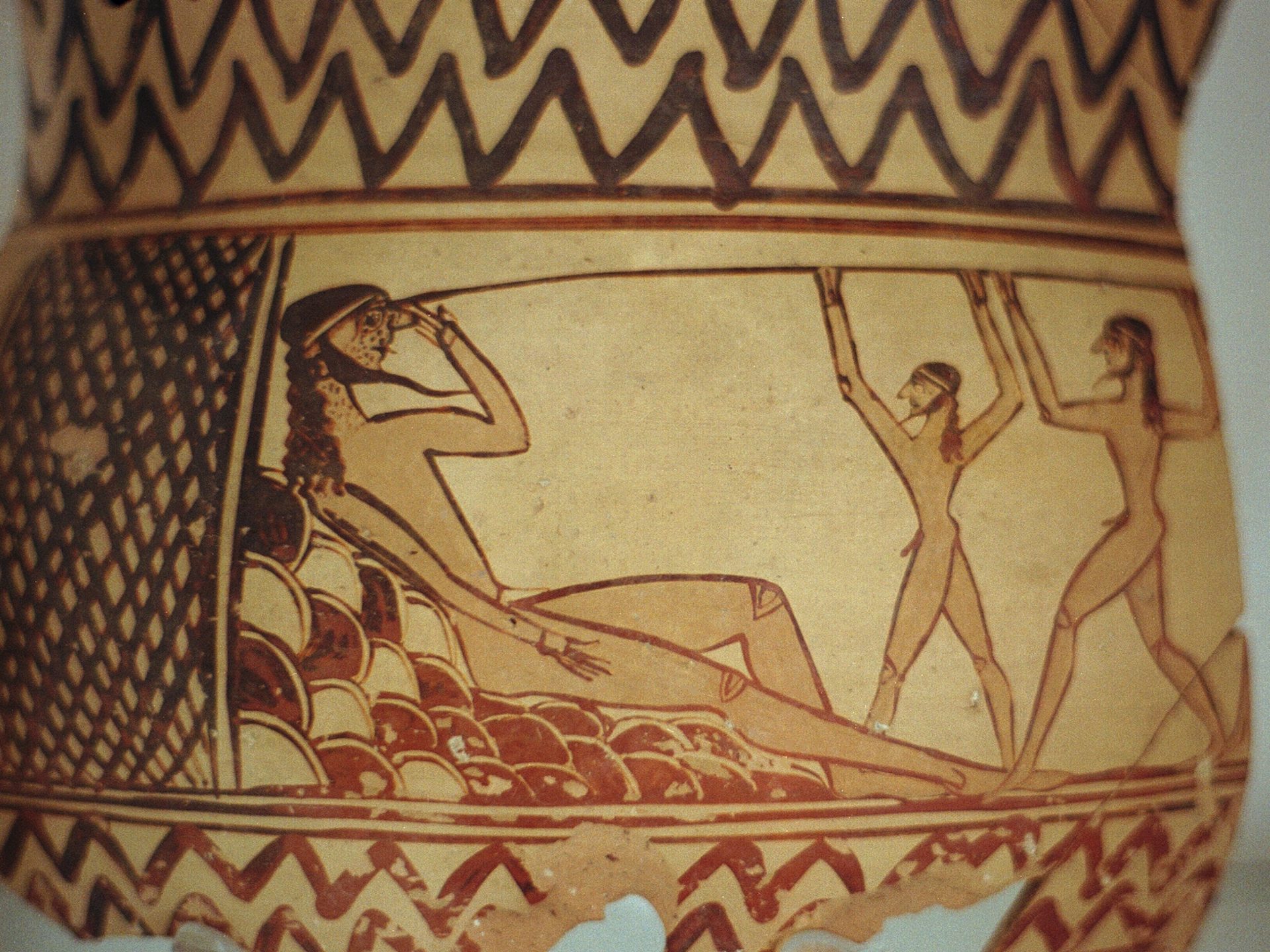

Poseidon was as unruly as the seas he controlled. Already in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, he exerted a powerful disruptive influence on the lives of gods and mortals. In the Odyssey, Poseidon bears a special grudge against Odysseus after the hero blinds Poseidon’s son Polyphemus, a vicious Cyclops who tried to eat Odysseus and his men.

Wishing to punish Odysseus for this act of violence, Poseidon prevented his homecoming for ten years. Odysseus was forced to wander the seas, losing all his ships and men, until Zeus himself finally commanded Poseidon to put aside his anger and allow Odysseus to return home.

Argive krater showing Odysseus blinding the Cyclops Polyphemus (7th century BCE)

Archaeological Museum of Argos / ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0Etymology

Poseidon was present in Greek religion from the earliest times: he was already well attested in the Mycenaean period (ca. 1600–1100 BCE). Originally written in a script called Linear B, which predates the Greek alphabet, the name appears in Mycenaean texts as Po-se-da-o or Po-se-da-wo-ne.

The name “Poseidon” likely has roots in two distinct words. The first of these is the Greek word posis, itself derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *pótis. Both words mean “husband,” “lord,” or “master.”

Some uncertainty surrounds the second linguistic element of Poseidon’s name. One interpretation holds that it comes from the root da-, meaning “earth” or “land,” which would make “Poseidon” translate to “lord of the earth,” or perhaps even “husband of the earth.” This latter translation indicated an association with the earth goddess Demeter. Indeed, the oldest Mycenaean Greek references to Poseidon pointed to an intimate—though imprecise—relationship with Demeter, and possibly Persephone.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Poseidon Ποσειδῶν Phonetic

IPA

[poh-SAHYD-n, puh-] /poʊˈsaɪd n, pə-/

Other Names

There were a few dialectic variations of Poseidon’s name in ancient Greece. In Homeric Greek he was called Ποσειδάων (Poseidaōn); in Aeolic he was Ποτειδάων (Poteidaōn); and in Doric he was Ποτειδάν (Poteidan), Ποτειδάων (Poteidaōn), and Ποτειδᾶς (Poteidas).

Epithets

Poseidon’s most important epithets were related to his capacity not as god of the sea but as god of earthquakes—hence his titles Enosichthōn or Ennosigaios (“earth-shaker”). He was also called Gaiēochos (“he who holds the earth”).

Other epithets attest to Poseidon’s role as god of the sea. These include Kyanochaitēs (“dark-haired”), Pelagios (“belonging to the sea”), and even Phykios (“full of seaweed”).

Finally, Poseidon was also called Hippios (“horseman”) because of his close association with horses.

Attributes

Poseidon was usually depicted as a mature god, powerfully built and bearded. His signature weapon was the trident, a three-pronged spear with which he did battle, mastered the sea, and caused earthquakes.

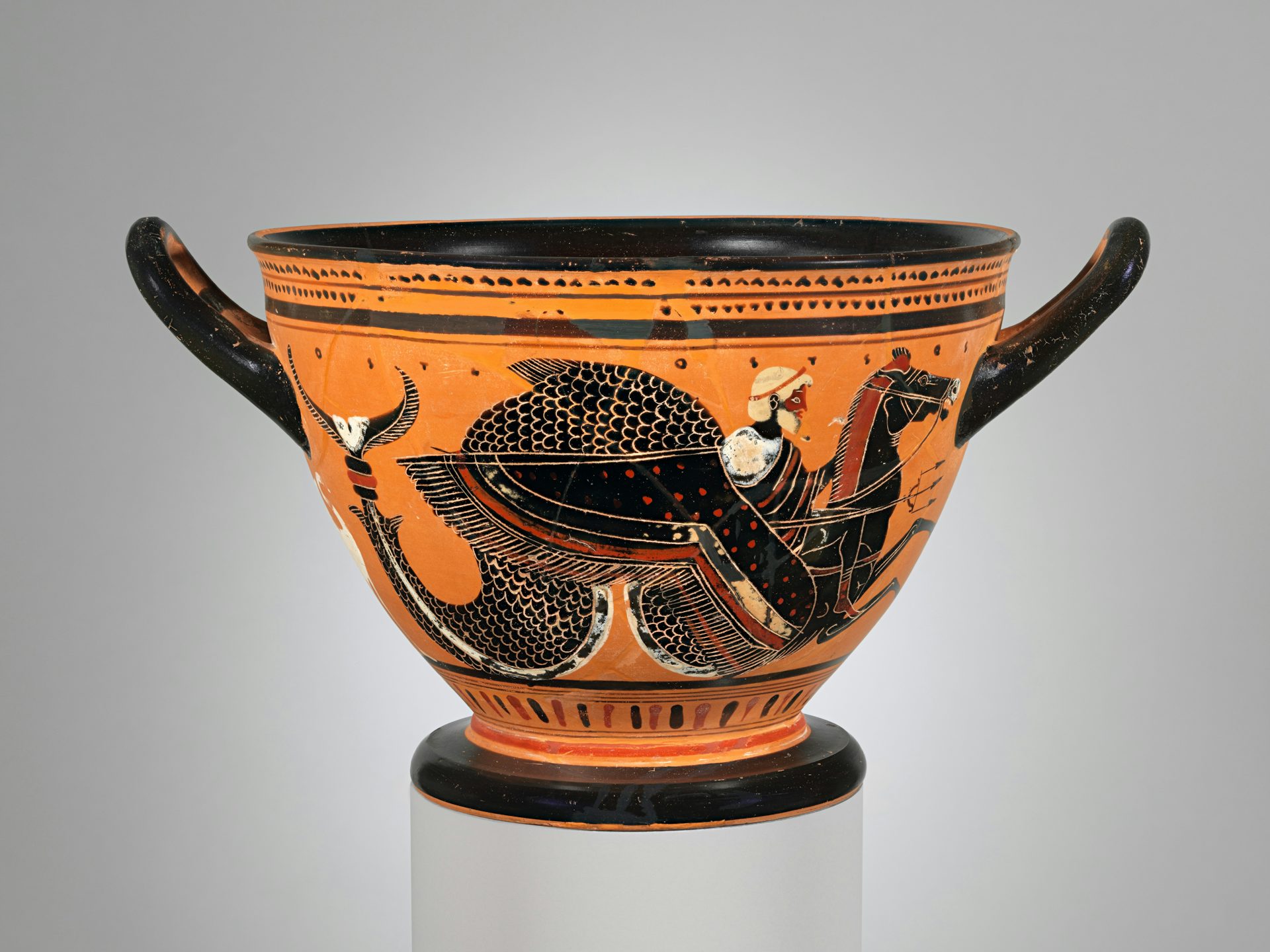

A god of horses, Poseidon was often pictured riding a chariot drawn by hippocampi—part-horse, part-snake creatures that glided across the waves. Poseidon was also associated with other animals of both land and sea, including dolphins, seahorses, tuna, and bulls.

Drinking vessel picturing Poseidon, god of the sea, riding a hippocompus (ca. 500 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn addition to his residence on Mount Olympus with the other gods, Poseidon was said to possess beautiful undersea palaces adorned with coral, pearls, and gems. He owned a stable of magnificent horses as well as numerous herds of horses throughout Greece.

Family

Poseidon wed Amphitrite, one of the nymphs known as the Nereids and a figure long associated with the sea (and salt water in particular). Together, they had three children: the merman Triton; Benthesicyme; and Rhodos, the patron goddess of Rhodes and future wife of Helios.[4]

Like other male deities, Poseidon was celebrated for his many infidelities and violent sexual conquests. Among his numerous illegitimate offspring were some of the most legendary figures in Greek mythology. With his grandmother Gaia, he sired the giant Antaeus, who did battle with Hercules during the Twelve Labors, and Charybdis, a sea monster that lurked in the straits of Messina and formed massive, relentless whirlpools to suck in unexpecting travelers.

He also reproduced with Aphrodite[5] and his sister Demeter. According to some traditions, he sired two children with the latter, including a small talking horse named Arion.[6]

Family Tree

Mythology

Origin

Along with his brothers and sisters—Hestia, Demeter, Hades, Hera, and Zeus—Poseidon was born of the union between Rhea and Cronus, Titans who ruled the universe before the rise of the Olympian pantheon. When Cronus discovered that one of his offspring was destined to overthrow him, he swallowed Poseidon and his other children. Eventually, mighty Zeus bested the Titan and forced him to regurgitate the children, including Poseidon.

According to one variant, Rhea saved Poseidon from being swallowed by Cronus just as she had saved Zeus. When Poseidon was born, Rhea pretended that she had given birth to a colt, which she gave to Cronus to swallow.[10] This myth reflects Poseidon’s association with horses.

Poseidon fought fiercely alongside Zeus and his other siblings in the cataclysmic conflict known as the Titanomachy. When they bested the Titans, Zeus, Hades, and Poseidon (being male and thus privileged to rule in Greek society) assumed control of the cosmos and divvied it up into various domains. The brothers drew lots, and Poseidon gained control of the seas, as well as all other waters.

East frieze of the Parthenon depicting Poseidon (left) seated next to Apollo and Artemis (fifth century BCE).

University of MichiganPublic DomainPoseidon and Zeus

A key element of the Poseidon mythos was the god's plots to undermine established orders, both human and divine. One older story, retold in regrettably brief detail in the Iliad, even featured Poseidon participating in a plot to overthrow Zeus. In this tale, Poseidon, Athena, and Hera conspired to trick Zeus into his throne and fasten him there.

Zeus was saved only by the vigilance of Thetis, the sea nymph, who summoned Briaraeus, one of the monstrous, hundred-handed creatures known as the Hecatoncheires. These creatures were the same beings responsible for the Olympians’ victory over the Titans and the Giants in the Titanomachy; thus, they could easily handle anything the rebellious gods threw at them.[11]

Foundation Myths

When the city of Athens was first founded, it was said that both Poseidon and Athena wished to be its patron god. Each of the gods was asked to show what they could offer to the new city. According to the best-known version of the myth, Poseidon struck a rock and produced a saltwater spring, while Athena produced the first olive tree.

Athena was chosen as the victor (sources vary on who the judges were). Poseidon, true to his irascible nature, flew into a rage and flooded much of Attica (the region of Greece in which Athens was located).[12]

A similar myth was told in Argos, though this time Poseidon’s rival was Hera. When Argos chose Hera as its patron rather than Poseidon, the unlucky god of the sea flooded much of the country (as he had done in Attica).[13]

The Walls of Troy

In one myth, Poseidon (together with Apollo) helped Laomedon, king of Troy, erect the fortifications of his great city.[14] According to some traditions, this task was ordered by Zeus as a punishment for the role Poseidon and Apollo had played in the Olympians’ revolt against him (see above).[15]

Poseidon performed the work as instructed, but nursed a bitter grudge for the affront, especially after Laomedon refused to pay him and Apollo the wages they had earned. When his period of service came to an end, he sent a monstrous sea creature to harass Troy. The creature was ultimately killed by Heracles, but when Laomedon tried to cheat Heracles as he had cheated Poseidon and Apollo, Heracles’ response was less subtle: he sacked Troy, killed Laomedon, and carried off his daughter Hesione.

Poseidon and the Homeric Epics

The Iliad

Poseidon was involved in the Trojan War, the ten-year conflict between the combined armies of Greece and the city of Troy. This war started after the Trojan prince Paris carried off Helen, the wife of a Greek king named Menelaus. Poseidon, along with several other Olympians, threw his considerable might behind the Greeks.[16]

In Homer’s Iliad, which describes a few fateful weeks during the final year of the war, Poseidon intervened several times to give aid to the Greeks. Like the other gods who meddled in the Trojan conflict, Poseidon’s assistance came mostly in the form of moral support.

At one critical moment in the battle, when the Achaeans seemed near defeat at the hands of the attacking Trojans, Poseidon raced to the battlefield and assumed the form of the prophet Calchas. He did so in order to avoid the detection of Zeus, who had ordered the gods to stay out of the affair. Poseidon’s resounding entry into battle was rendered beautifully in the Iliad:

Forthwith then he went down from the rugged mount, striding forth with swift footsteps, and the high mountains trembled and the woodland beneath the immortal feet of Poseidon as he went. Thrice he strode in his course, and with the fourth stride he reached his goal, even Aegae, where was his famous palace builded in the depths of the mere, golden and gleaming, imperishable for ever. Thither came he, and let harness beneath his car his two bronze hooved horses, swift of flight, with flowing manes of gold; and with gold he clad himself about his body, and grasped the well-wrought whip of gold, and stepped upon his car, and set out to drive over the waves. Then gambolled the sea-beasts beneath him on every side from out the deeps, for well they knew their lord, and in gladness the sea parted before him; right swiftly sped they on, and the axle of bronze was not wetted beneath; and unto the ships of the Achaeans did the prancing steeds bear their lord.[17]

Despite Poseidon’s aid, the Greeks were still suffering tremendous losses that threatened their collective resolve. Even Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek army, was shaken; he proposed a retreat so that the Achaeans might regain their strength.

Once again, Poseidon intervened—this time with help from Hera, who distracted Zeus with her feminine charms and lured him into a deep slumber. Seizing the moment, Poseidon revealed himself and led his troops in a terrific assault that left Hector wounded and the Greeks ascendant.

The Trojans Repulsing the Greeks by Giovanni Battista Scultori (1538). Poseidon is possibly rendered in the foreground, sword in hand, with the body of Hector protected by another warrior lying beneath him.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhen Zeus finally awoke to the sound of Poseidon bellowing in fury from the battlefield, he ordered the disobedient sea god to retreat from the battle immediately. Poseidon conceded—not out of fear, he assured the other gods, but because of his enormous respect for the Father of Olympus.[18]

The Odyssey

After Troy had been brought to ruin, Poseidon focused his seemingly inexhaustible rage on Odysseus, the great hero whose long journey home was immortalized in Homer’s Odyssey.

Though Odysseus had fought on the side of the Achaeans, he and his crew happened to land on an island inhabited by Polyphemus, a Cyclops and one of Poseidon’s sons. When Polyphemus began eating members of the crew, Odysseus and his few remaining men devised a plan to blind the creature. Using great cunning, they tricked him into drinking himself into a stupor and blinded him when he was inebriated.

While the act allowed Odysseus and the others to escape from the Cyclops’ clutches, it also earned them the wrath of Poseidon, a god more than capable of waylaying Odysseus on his voyage home. Truly, there would be no Odyssey without Poseidon. At one point, Poseidon sent a storm to shipwreck Odysseus as he was leaving the island of Calypso; the sea god would later lure Odysseus near another one of his children, the maelstrom-producing sea monster Charybdis.

Worship

Temples

Poseidon held temples throughout the ancient Greek world, but the most important ones were located at Corinth, Helice (in Achaea), and Onchestus (in Boeotia).

There was an altar to Poseidon in the Erechtheion in Athens, a shrine dedicated to one of the city’s early founders and kings. Near this shrine was the spring that Poseidon was said to have created when he and Athena competed for the city. It was thought that a stone by the spring still bore the sign of Poseidon’s trident where the god had once smote it.[19]

Many of Poseidon’s temples were built on the coast or on capes and islands. One remarkably well-preserved example is the Temple of Poseidon on Cape Sounion, about 43 miles southeast of Athens.

The Temple of Poseidon (444–440 BCE). Built on Cape Sounion, just south of Athens on the Attic peninsula and near the center of the god's worship, this is perhaps the oldest and best maintained of Poseidon's temples.

A. Savin / Wikimedia CommonsCC BY-SA 3.0Festivals

The most important of Poseidon’s festivals were the Isthmian Games, one of the four major Greek athletic festivals (the other three were the Olympic Games and Nemean Games, both in honor of Zeus, and the Pythian Games, in honor of Apollo). These were held every two years near the great Temple of Poseidon in Corinth. Participants would compete in various athletic and musical competitions for the first prize, which was a crown of celery leaves.

Poseidon was also worshipped throughout the Greek world with sacrifices of bulls, other livestock, and even horses.[20] Horse sacrifices were unusual in Greece, but Poseidon was, after all, the god of horses (hence his title Hippios). There are also vase paintings showing that tuna were sometimes sacrificed to Poseidon.

Pop Culture

Thanks to his central role in the Homeric epics, Poseidon has maintained a lively presence in contemporary popular culture. There have been many film and television versions of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and Poseidon is often featured as a main character.

Poseidon briefly appears in the Disney animated films Hercules (1997) and The Little Mermaid (1989); in the latter he takes the guise of the benevolent King Triton, also known as Neptune (the Roman version of Poseidon).

The sea god also figures prominently in Percy Jackson and the Olympians, a book series by Rick Riordan in which Poseidon plays the father of the eponymous hero.

Poseidon has frequently appeared in popular video games, including the God of War and Assassin’s Creed series.

Poseidon is also the subject of many vivid, colorful, and dramatic internet illustrations on forums such as Pinterest. In these popular manifestations, Poseidon has maintained much of his ancient masculine vigor. Often appearing heavily muscled and bearded, he can be seen wielding his fearsome trident, rising menacingly out of the frothy seas, and intimidating his opponents into submission.