Amphitrite

Amphitrite by François Théodore Devaulx (1866). North façade of the Cour Carrée in the Louvre Palace.

JastrowCC BY 2.5Overview

Amphitrite, who was either a Nereid or an Oceanid, was one of the most important and powerful gods of the sea. She eventually married Poseidon, the Olympian god who ruled over the sea, though she at first rejected him. In time, she gave her husband Poseidon several important children, including the merman Triton as well as Benthesicyme, Cympoleia, and Rhode. Amphitrite was widely recognized in ancient Greece, appearing in art, literature, and cult.

Etymology

The etymology of the name “Amphitrite” (Greek Ἀμφιτρίτη, translit. Amphitrítē) is uncertain. Its first element seems to be the Greek prefix ἀμφί- (amphí-), meaning “around, on each side,” while the second element resembles the Greek adjective τρίτος (trítos), meaning “third,” but also the verb τιτραίνω (titraínō), meaning “to pierce.”

Thus, Amphitrite’s name could possibly be interpreted as either “around the third” or, alternatively, as the only slightly less nonsensical “piercing on each side.” Which of these etymologies is correct—or whether the true etymology is entirely different—is impossible to know.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Amphitrite Ἀμφιτρίτη (Amphitrítē) Phonetic

IPA

[am-fi-TRAHY-tee] /ˌæm fɪˈtraɪ ti/

Alternate Names

In Roman literature and religion, Amphitrite’s counterpart appears to have been Salacia, a minor goddess of saltwater who was the consort of Neptune (the Roman counterpart to Poseidon).

Titles and Epithets

As a daughter of Nereus, Amphitrite was a “Nereid” (Νηρηΐς, Nērēḯs); for sources that made her a daughter of Oceanus, of course, she was an “Oceanid” (Ὠκεανίς, Ōkeanís).

Amphitrite also had a number of colorful individual epithets in ancient literature. She could be described as εὔσφυρος (eúsphyros, “fair-ankled”), βοῶπις (boôpis, “ox-eyed”), or κυανῶπις (kyanôpis, “dark-eyed”), terms that highlighted her beauty; or by the more obscure χρυσηλάκατος (chrysēlákatos, “she of the golden spindle”); or even as Ποσειδωνία (Poseidōnía, “she who is Poseidon’s”), emphasizing her role as Poseidon’s queen. Amphitrite may have also shared the Homeric epithet ἁλοσύδνη (halosýdnē, “sea-born”) with her sister Thetis.[1]

Attributes

Like the other Nereids, Amphitrite was a beautiful sea nymph. She lived in the depths of the sea with her husband Poseidon. Some poets sang of her many underground treasures, which included a magnificent crown and luxurious cloak that she would eventually give to the hero Theseus.[2]

As a Nereid and the wife of Poseidon, Amphitrite was the queen of the sea. She was tremendously powerful, said to be able to calm the waves and even the wind.[3]

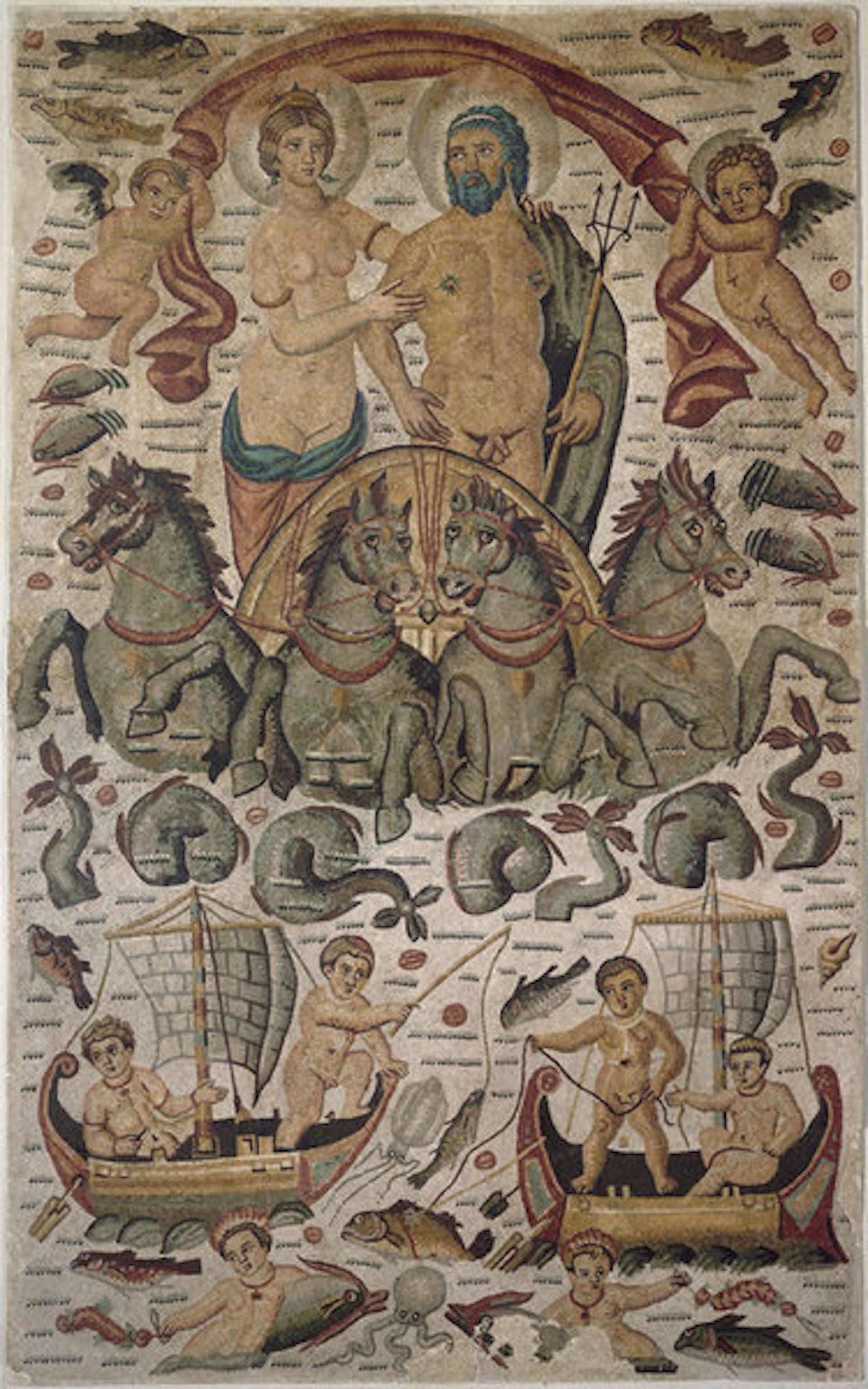

Amphitrite was quite popular in ancient art. She could be shown with her husband Poseidon or on her own. She would be imagined in the form of a beautiful young woman, similar to Aphrodite except that in some cases she was represented with crab-claw horns growing out of her head. It was common for artists to have her in the company of sea creatures, such as tritons and dolphins, who drew her chariot or on whose backs she would ride through the waves.[4]

Mosaic from Cirta, a Roman settlement in North Africa (ca. 315–325 CE)

Louvre Museum, Paris, FrancePublic DomainFamily

According to the best-known account, recorded in Hesiod’s Theogony, Amphitrite was a daughter of the sea gods Nereus and Doris and thus one of the fifty sea nymphs known as “Nereids.”[5] But according to another tradition, Amphitrite was a daughter of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys—a genealogy that served to associate her with the “Oceanids,” a different group of sea nymphs.[6]

In the tradition that Amphitrite was the daughter of Nereus and Doris, her siblings would have included the other Nereids as well as—according to some—a brother named Nerites who was a companion (or perhaps a lover) of Poseidon.[7] In the tradition that Amphitrite was the daughter of Oceanus and Tethys, her siblings would have been the other Oceanids as well as the three thousand Potamoi (that is, the “Rivers”).

Amphitrite married Poseidon, one of the Olympians and the ruler of the sea.[8] Together they had several children: Triton, a merman who was regarded as a sea god, just like his parents;[9] Benthesicyme, an obscure goddess or nymph who lived with her husband in Ethiopia;[10] and Rhode, the namesake of the island of Rhodes (which was sacred to the sun god Helios).[11]

In one unusual tradition, Amphitrite was also called the mother of the Nereids (even though she herself was usually counted as one of the Nereids!).[12]

Mythology

Poseidon’s Queen

Amphitrite became the wife of Poseidon after the powerful Olympian fell in love with her. There are two versions of how this happened. In a local myth told on the Aegean island of Naxos, it was said that Poseidon spotted Amphitrite dancing on Naxos with her sisters, the other Nereids. Smitten, he kidnapped her and made her his wife.[13]

But in another myth, which seems to have become the better known version, Amphitrite ran away from Poseidon when he first sought her hand in marriage, hiding herself away in the depths of the sea or with the Titan Atlas. Poseidon sent numerous servants to search for her. Eventually, she was found by the dolphin, who pleaded his master’s love so persuasively that Amphitrite finally agreed to marry Poseidon. Deeply grateful, Poseidon made the dolphin into a constellation.[14]

The Return of Neptune by John Singleton Copley (ca. 1754)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOther Myths

Though a widely recognized goddess, Amphitrite did not have many myths of her own. She did, however, make a few scattered appearances.

In one tradition, the Athenian hero Theseus was challenged by Minos as soon as he arrived in Crete. When Minos—the king of Crete and a son of Zeus—heard that Theseus claimed to be the son of Poseidon, he demanded that the hero prove his claim: he tossed a precious ring into the sea, saying that if Theseus was really the son of Poseidon he should not have any difficulty retrieving it.

The bold Theseus immediately dived into the sea. There, he was greeted by the sea creatures, the Nereids, and, above all, by Amphitrite, who received her husband’s illegitimate son kindly and sent him away with magnificent gifts (proving herself exceptional among the notoriously vindictive stepmothers of Greek mythology). The scene is charmingly rendered in the words of the poet Bacchylides:

… sea-dwelling dolphins swiftly carried great Theseus to the home of his father, lord of horses; and he came to the hall of the gods. There he saw the glorious daughters of prosperous Nereus, and was afraid; for brightness shone like fire from their splendid limbs, and ribbons woven with gold whirled around their hair. They were delighting their hearts in a dance, with flowing feet. And he saw in that lovely dwelling the dear wife of his father, holy, ox-eyed Amphitrite. She threw a purple cloak around him and placed on his curly hair a perfect wreath, dark with roses, which once deceptive Aphrodite had given her at her marriage.[15]

Another, more obscure myth tells of how the daughters of the Giant Alcyoneus cast themselves into the sea after their father was killed fighting against the Olympians in the Gigantomachy. Pitying the poor girls, Amphitrite transformed them into birds—“halcyons,” more commonly known today as “kingfishers.”[16]

Worship

Amphitrite was worshiped alongside her husband Poseidon, especially on the Cyclades Islands of the Aegean Sea. We know, for example, that she and Poseidon were both honored on Delos, one of the most important Greek islands (known especially for its sanctuary of Apollo).[17] Amphitrite also shared a temple with Poseidon on Tenos, one of the larger islands of the Cyclades. This temple contained two massive cult statues of Poseidon and Amphitrite. It was part of a larger sanctuary located outside of the city in a sacred grove and was known for offering asylum rights.[18]

Amphitrite seems to have been worshiped with Poseidon at various other sites throughout Greece where she was represented in cult images in Poseidon’s temples.[19] She was probably also worshiped alongside her sisters, the Nereids, who were honored at a handful of cult sites throughout ancient Greece.[20]

Pop Culture

Amphitrite continues to be remembered for her role as queen of the sea. Numerous ships have been named for her, including seven ships of the British Royal Navy and three ships of the United States Navy. There is a shallow ceremonial pool on the grounds of the United States Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York known as “Amphitrite Pool,” complete with a statue of Amphitrite.

Amphitrite’s legacy is not limited to navies. Among other things, a genus of the marine worm family Terebellidae has been named after Amphitrite, and in 1936 Australia put an image of Amphitrite on a postage stamp commemorating the opening of the submarine communications cable running from Stanley, Tasmania to Apollo Bay, Victoria.

Amphitrite on an Australian postage stamp commemorating the submarine communications cable from Stanley, Tasmania to Apollo Bay, Victoria (1936)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic Domain