Antaeus

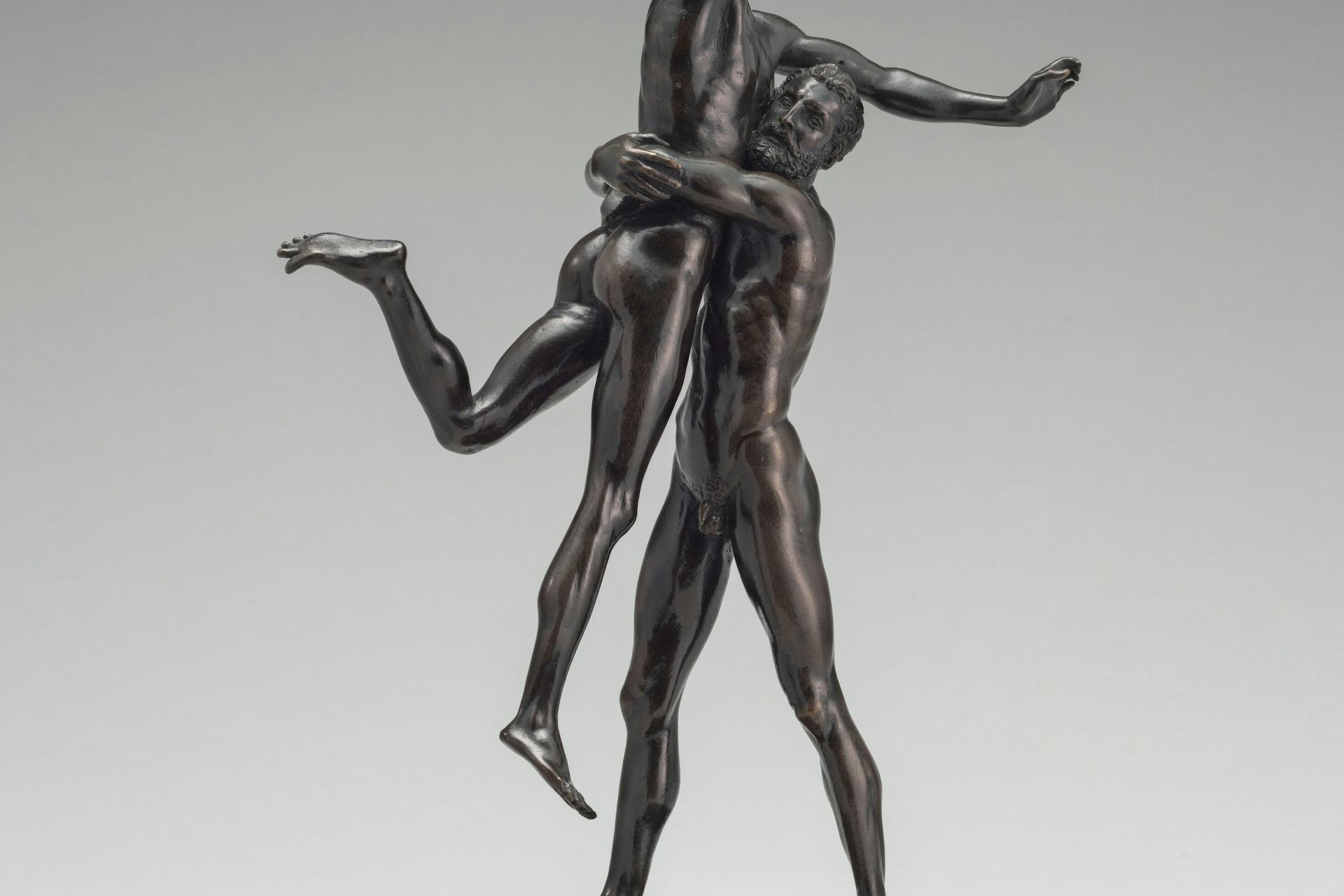

Hercules and Antaeus. Paduan sculpture (ca. 1525).

National Gallery of Art (US)Public DomainOverview

Antaeus was a son of Poseidon and Gaia who made his home in the deserts of Libya. He was extremely large and strong and a formidable fighter; but he was also cruel, forcing strangers into wrestling matches that invariably ended in their death.

Because he could not be hurt as long as he was touching the earth, Antaeus was virtually invincible. But he was finally defeated by Heracles while the hero was traveling through Africa. In what eventually became the standard tradition, Heracles lifted Antaeus into the air so that he was no longer in contact with the earth; in this way, he was able to bypass Antaeus’ invulnerability.

The wild, violent Antaeus—like other fearsome thugs and monsters of Greek mythology—most likely represented how the Greeks viewed foreign “barbarians.” And like many of his fellow brutes, Antaeus was finally defeated by Heracles, the great champion of Greek heroic values and civilization.

In time, however, Antaeus was embraced as a culture hero by the Berber people of Morocco and Tunisia, to whom he was known as “Anti.”

Etymology

The name “Antaeus” (Greek Ἀνταῖος, translit. Antaîos) appears to be connected with Greek words denoting opposition—for instance, the preposition antí, meaning “opposite, instead of,” and the verb antiáō, “to come up against, oppose.” These words are in turn derived from the Indo-European *h₂ent-, meaning “face, front.” “Antaeus” is thus understood as “the opponent.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Antaeus Ἀνταῖος (Antaîos) Phonetic

IPA

[an-TEE-uhs] /ænˈti əs/

Attributes

Locales

Antaeus was a gigantic wrestler from the region of Libya in North Africa.[1] Some ancient sources left his location at that, but others were more precise, locating Antaeus’ home either in Irasa (not far from Cyrene, just west of Egypt),[2] near the Lixos River (possibly the modern Draa),[3] or in Tangiers (which he was sometimes said to have founded).[4]

Appearance and Characteristics

Antaeus was represented as extremely large and strong. In antiquity, a skeleton sixty cubits long (approximately ninety feet)—supposedly excavated in Libya—was popularly identified as Antaeus’ enormous remains.[5]

Antaeus was a skilled wrestler and was sometimes even hailed as one of the chief innovators of wrestling as an art.[6] According to one account, Antaeus was also an expert at throwing the solos, a kind of iron discus; after Heracles killed Antaeus, he took his solos as a trophy. Heracles later gave it to Peleus, who in turn passed it down to his son Achilles.[7]

Antaeus’ most famous attribute, however, was his partial invulnerability. According to a popular (though perhaps rather late) tradition, Antaeus could not be hurt as long as he was in contact with the earth—a gift from his mother Gaia, the goddess who embodied the earth.[8] This power allowed Antaeus to defeat all of his opponents—at least until he met Heracles.[9]

Iconography

Antaeus was a popular subject in ancient Greek art and later spread to Etruscan and Roman art as well. He could be found in vase paintings, reliefs, sculptures, wall paintings, and engraved gemstones. Artists represented Antaeus as quite large and muscular; to illustrate his barbaric and wild nature, he was often depicted as rather hairy as well.

Antaeus appeared in art from as early as the sixth century BCE (for instance, on the metopes of the Temple of Hera at Foce del Sele), almost always in his fateful battle with Heracles.

Attic red-figure krater painted by Euphronios (ca. 515 BCE) showing Heracles (left) wrestling with Antaeus (right)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainFamily

Antaeus was a child of Poseidon, the god of the sea,[10] and Gaia, the primordial goddess of the earth.[11] This made him a brother of the Pygmies, who were also said to have been born from the union of these two important gods.[12]

Antaeus’ wife was named Iphinoe in early literature.[13] In later accounts, however, she was called Tinge, the namesake or “eponym” of the city of Tangiers.[14] Antaeus and his wife seem to have had a daughter named Alceis.[15]

Mythology

Origins

The myth of Antaeus is sometimes thought to have evolved as a result of Greek contact with Libya. Though relations between the Greeks and the Libyans were friendly at first, the growing power of the Greek colony of Cyrene in North Africa led to tensions between the two civilizations by the middle of the sixth century BCE.

This tense climate may have given rise to the Greek myth of the Libyan Antaeus—a wild, violent, and impious brute who embodied the rough qualities that the Greeks came to associate with the “barbaric” Libyans.

Antaeus and Heracles

Antaeus was best known as one of the brutish opponents that Heracles fought and defeated over the course of his adventures. Antaeus would force strangers who came to his land to face him in a wrestling match. When he defeated his opponents—as he invariably did—he would use their skulls to decorate the temple of his father Poseidon.[16]

Heracles met Antaeus when one of his Twelve Labors took him through North Africa.[17] Antaeus challenged the famous hero to a wrestling match, just as he had challenged all previous passersby. But this proved to be a fatal mistake.

In the most familiar account, Heracles soon caught on that Antaeus was invincible as long as he was in contact with the earth, so he simply lifted him into the air in order to kill him. The Roman epic poet Lucan describes how Heracles

lifted on high the giant who struggled to gain the ground. Earth was unable to convey strength into the frame of her dying son; for Alcides [i.e., Heracles], standing between, gripped the breast that was already stiff with cold obstruction, and refused for long to trust his foe to the earth.[18]

After killing Antaeus, Heracles slept with his wife and even fathered a son by her.

In the earliest traditions, Antaeus’ wife was named Iphinoe, and the son she had by Heracles was named Palaemon.[19] But later, as Antaeus was increasingly adopted as a Libyan culture hero, Antaeus’ wife acquired the name Tinge (the eponym of Tangiers). The son she had with Heracles—who in later literature was called Sophax rather than Palaemon—was said to have been the ancestor of the kings of Mauretania.[20]

Worship

Antaeus soon became an important figure in the religion and mythology of various North African peoples. By the Hellenistic period (323–30 BCE), he had begun to be identified with a form of the Egyptian god Seth. His cult, located in Tjebu in Upper Egypt, was known as “Antaeopolis”; an episode in Seth’s battle against Isis was said to have occurred there.[21]

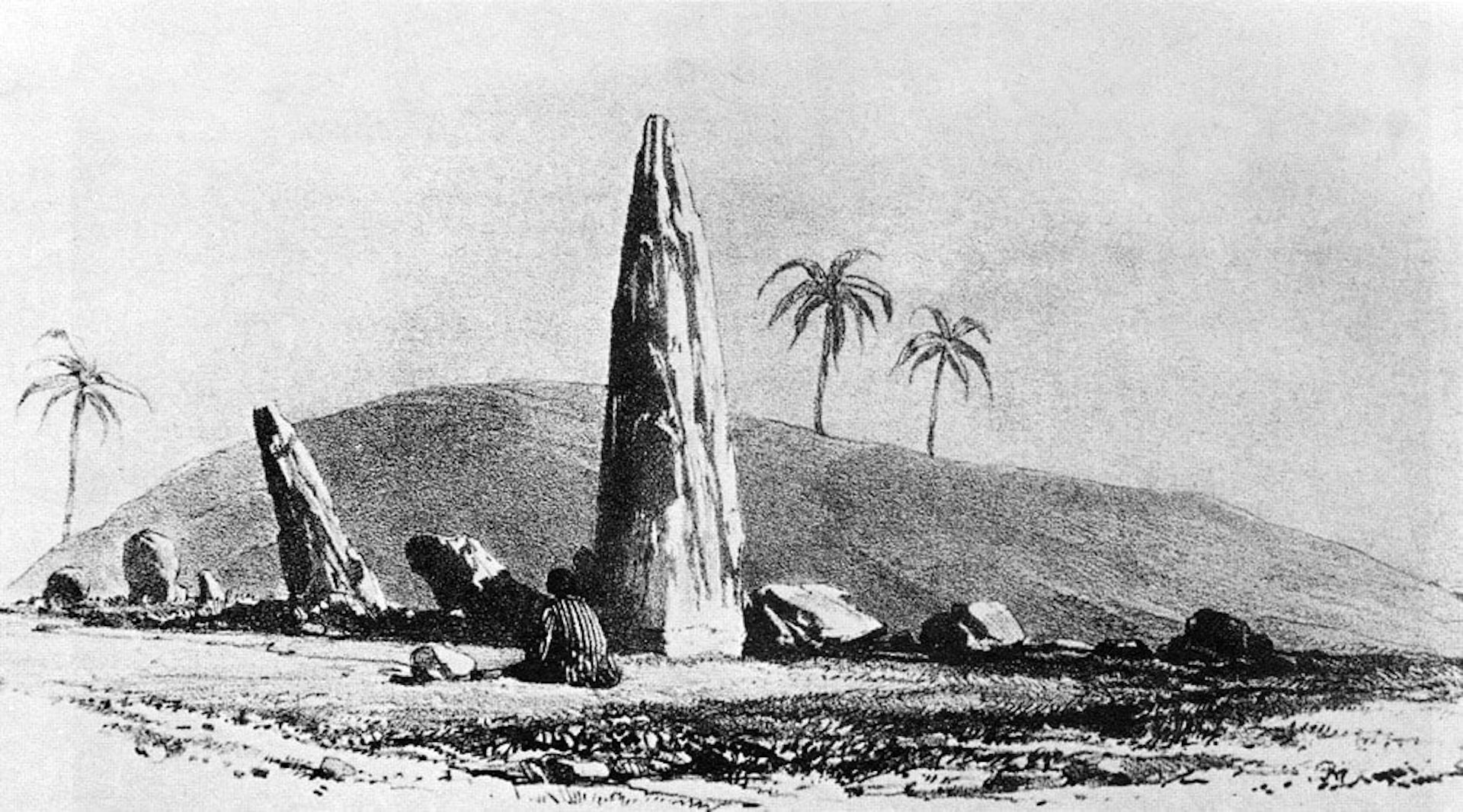

Antaeus was especially important in the mythology of the Berbers, who knew him as Anti. Antaeus’ tomb, shown near Tangiers, was a huge mound of earth, likely identical with the elaborate mound known today as Msouda.

The mound was supposedly excavated in antiquity and yielded a skeleton of gigantic size, believed to be the remains of Antaeus.[22] It was said that whenever the tomb was opened, it would rain until the mud closed it up again.[23]

Drawing of the Msoura stone circle in northern Morocco, possibly the site identified in antiquity as the tomb of Antaeus

Arthur de Capell Brooke, Sketches in Spain and Morocco, Vol. 2 (1831)Public DomainPopular Culture

Antaeus has remained an important figure in Western culture, appearing, for instance, in Canto 31 of Dante’s Inferno. He continues to surface in more recent adaptations of the Greek myths. In the extremely popular Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, for example, Antaeus is a “half-giant” who fights Percy Jackson.