Hector

Hector Admonishes Paris for his Softness and Exhorts him to Go to War by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1786)

Augusteum, OldenburgPublic DomainOverview

Hector was a prince and hero of Troy, the firstborn son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, and thus the heir to the Trojan throne. He married the princess Andromache, with whom he had a son named Astyanax. Hector was a great warrior, much admired not only for his military skill and bravery but also for his nobility and sense of duty. During the Trojan War, he led the Trojan forces against the invading Greeks for nearly ten years. When Achilles, the greatest of the Greek heroes, refused to fight because of a quarrel with the Greek commander Agamemnon, Hector nearly managed to drive the Greeks from Troy once and for all.

But when Hector killed Achilles’ best friend Patroclus in battle, Achilles turned the full force of his anger on Hector. The two heroes fought before the walls of Troy, and Hector ultimately fell to Achilles. With Hector dead, Troy had lost its greatest protector.

Who were Hector’s parents?

In most accounts, Hector’s parents were said to be Priam and Hecuba, the king and queen of Troy. As their firstborn son, Hector was heir to the Trojan throne. His younger brothers included Paris—who sparked the Trojan War by carrying off Helen—as well as the warrior Deiphobus and the prophet Helenus. His sisters included Cassandra, a prophet whose curse was that no one would believe her predictions.

An alternative tradition, however, claimed that Hector’s real father was not Priam but the god Apollo. According to this tradition, Apollo had had an affair with Priam’s wife Hecuba, and Hector was the result of this union.

Hector Admonishes Paris for his Softness and Exhorts him to Go to War by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1786)

Augusteum, OldenburgPublic DomainWhom did Hector marry?

Hector married Andromache, a princess from the neighboring city of Cilician Thebes (not to be confused with the more famous Thebes in central Greece). Together they had a son named Astyanax.

Following Hector’s death and the defeat of the Trojans by the Greeks, Andromache was taken captive and enslaved. Fearing that Astyanax would try to avenge his father if he were allowed to grow up, the Greeks violently murdered the boy.

Hector Taking Leave of Andromache: The Fright of Astyanax by Benjamin West (1766)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHow did Hector die?

Hector was killed during the ninth year of the Trojan War by Achilles, the greatest of the Greek heroes. Achilles wished to avenge his friend Patroclus, whom Hector had slain in battle.

Hector faced Achilles in single combat before the walls of Troy. Though he initially tried to run away from the menacing Achilles, Hector finally realized that there was no escape. He fought the famous Greek warrior, who quickly killed Hector with his spear.

Neck of Attic red-figure volute-krater (mixing bowl) showing Achilles (left) fighting Hector (right) by the Berlin Painter (ca. 490 BCE)

British Museum, London / ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0Hector Kills Patroclus

During the ninth year of the Trojan War, Achilles, the most formidable warrior in the Greek army, withdrew from the fighting because of a quarrel with the Greek general Agamemnon. Hector took advantage of Achilles’ absence to push the Greeks back, almost driving them out of Troy.

But Achilles’ best friend Patroclus could not stand by and watch his friends die, so he borrowed Achilles’ armor and led his troops, the Myrmidons, into battle. Patroclus managed to drive the Trojans out of the Greek camp but was ultimately killed by Hector.

Achilles, devastated at the loss of his friend, returned to the fighting the next day. He faced Hector before the walls of Troy and killed him in order to avenge Patroclus.

Achilles Displaying the Body of Hector at the Feet of Patroclus by Joseph-Barthélemy Lebouteux (1769)

Beaux-Arts de ParisPublic DomainEtymology

The name “Hector” is derived from *hechein, an archaic form of the common Greek verb echein, meaning “to have” or “to hold.”[1] Hector’s name could thus be translated as “he who holds fast,” a moniker that reflects his role as the enduring defender of Troy.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Hector Ἕκτωρ Phonetic

IPA

[HEK-ter] /ˈhɛk tər/

Titles and Epithets

The most famous of Hector’s epithets was probably hippodamos, “tamer of horses,” though he boasted numerous other epithets as well. Some were unique to him, such as androphanos, “man-slaying”; korythaiolos, “he of the shining helmet”; and chalkokorystēs, “clad in bronze.” Some he shared with other heroes, including diiphilos, “beloved of Zeus”; dios, “brilliant” or “godlike”; megas, “great”; and phaidimos, “glorious.”

Attributes

Hector was a great warrior, known for his bravery and nobility. As the eldest son of the Trojan king and queen, Priam and Hecuba, Hector was also the heir to the throne of Troy.

One late source, published under the pseudonym Dares of Phrygia, claimed to offer an eyewitness description of Hector:

Hector spoke with a slight lisp. His complexion was fair, his hair curly. His eyes would blink attractively. His movements were swift. His face, with its beard, was noble. He was handsome, fierce, and high-spirited, merciful to the citizens, and deserving of love.[2]

Like many of the warrior-heroes of Greek mythology, Hector possessed magnificent armor and weapons. Especially celebrated was his helmet, said to have been a gift from the god Apollo.[3] In one poignant passage from Homer’s Iliad, Hector removes his helmet to embrace his young son Astyanax, who is “seized with dread of the bronze and the crest of horse-hair, as he marked it waving dreadfully from the topmost helm.”[4]

Apulian red-figure column krater showing Hector's son Astyanax, on Andromache's knees, stretching to touch his father's helmet. From Ruvo in Italy, ca. 370–360 BCE. National Museum of the Palazzo Jatta in Ruvo di Puglia (Bari), Italy.

JastrowPublic DomainHomer also describes Hector’s “silver-studded sword with its scabbard and well-cut baldric,”[5] which Hector gave to the Greek hero Ajax as a gift after the two fought a duel to a draw. According to some sources, Ajax would later use this very sword to kill himself.

In ancient art, Hector was represented as a strong warrior. He was most often depicted in battle or being dragged behind the chariot wheels of Achilles.[6]

Family

Hector was the firstborn son of Priam, the king of Troy, and his queen, Hecuba. Through Priam, he was a direct descendant of the founders and early kings of Troy: Dardanus, Tros, and Ilus. According to some ancient authors, however, Hector was in fact the son of the god Apollo, who in this version had had an affair with Hecuba.[7]

In addition to Hector, Priam had many other children—both by Hecuba and by other women. According to Homer, Priam had fifty sons and twelve daughters;[8] other traditions gave him even more children. Thus, Hector had numerous siblings and half-siblings, including Paris, Cassandra, Helenus, Deiphobus, Troilus, and Polyxena.

Hector married Andromache, a princess from the neighboring kingdom of Thebes (not to be confused with the more famous Thebes in Greece). Together they had a son named either Astyanax or Scamandrius (according to Homer, Scamandrius was the child’s given name, while Astyanax, “lord of the city,” was the popular name used by the people of Troy).[9] Other sources assigned them additional sons, including Laodamas,[10] Oxynius,[11] or Amphineus.[12]

In his tragedy Andromache, Euripides mentions that Hector also had illegitimate children with other women, but this detail is likely an invention unique to Euripides.[13]

Mythology

Origins of the Trojan War

Hector was the eldest and most beloved of King Priam’s sons. He was a great warrior and a strong leader, fiercely devoted to his family and his city. He was also the heir to the throne of Troy, a wealthy city located on the northwestern tip of modern Turkey.

When Hector’s younger brother Paris went to the Greek city of Sparta and returned with Helen, the beautiful wife of the Spartan king, the Greeks were not happy. They demanded that Helen be returned; when these orders were dismissed, they sailed to Troy with a huge army to get her back by force. Though Hector disapproved of Paris’ actions, he took it upon himself (as the greatest warrior in Troy) to lead his city against the invading Greeks.

Hector distinguished himself in the Trojan War right away. According to the common tradition, it was Hector who killed the first of the Greeks to set foot on Trojan soil, a hero named Protesilaus.[14] But despite Hector’s bravery, the Greeks managed to win the beachhead of Troy. The Trojans retreated behind their strong walls, and the decade-long Trojan War began.

Hector in the Iliad

The best-known ancient text on the Trojan War is Homer’s Iliad, which describes in detail a few eventful days during the ninth year of the ten-year war. In the Iliad, Hector is represented as the greatest warrior in Troy, as well as the commander of their army.

Paris and Menelaus

According to Homer, when the Greeks and Trojans had both become weary of the long war, Helen’s husband Menelaus challenged Paris to a duel: if Menelaus won, Paris would return Helen, while if Paris won, he could keep Helen and the Greeks would go home. Paris did not want to accept Menelaus’ challenge, but when Hector saw him cowering, he reproached him angrily:

Evil Paris, most fair to look upon, thou that art mad after women, thou beguiler, would that thou hadst ne'er been born and hadst died unwed. Aye, of that were I fain, and it had been better far than that thou shouldest thus be a reproach, and that men should look upon thee in scorn. Verily, methinks, will the long-haired Achaeans laugh aloud, deeming that a prince is our champion because a comely form is his, while there is no strength in his heart nor any valour…

Wilt thou indeed not abide Menelaus, dear to Ares? Thou wouldest learn what manner of warrior he is whose lovely wife thou hast. Then will thy lyre help thee not, neither the gifts of Aphrodite, thy locks and thy comeliness, when thou shalt lie low in the dust. Nay, verily, the Trojans are utter cowards: else wouldest thou ere this have donned a coat of stone by reason of all the evil thou hast wrought.[15]

At Hector’s insistence, Paris fought Menelaus. But just as Menelaus seemed poised to defeat the young prince, Paris managed to escape with the help of the goddess Aphrodite, who loved him dearly. Thus, the war went on as before.

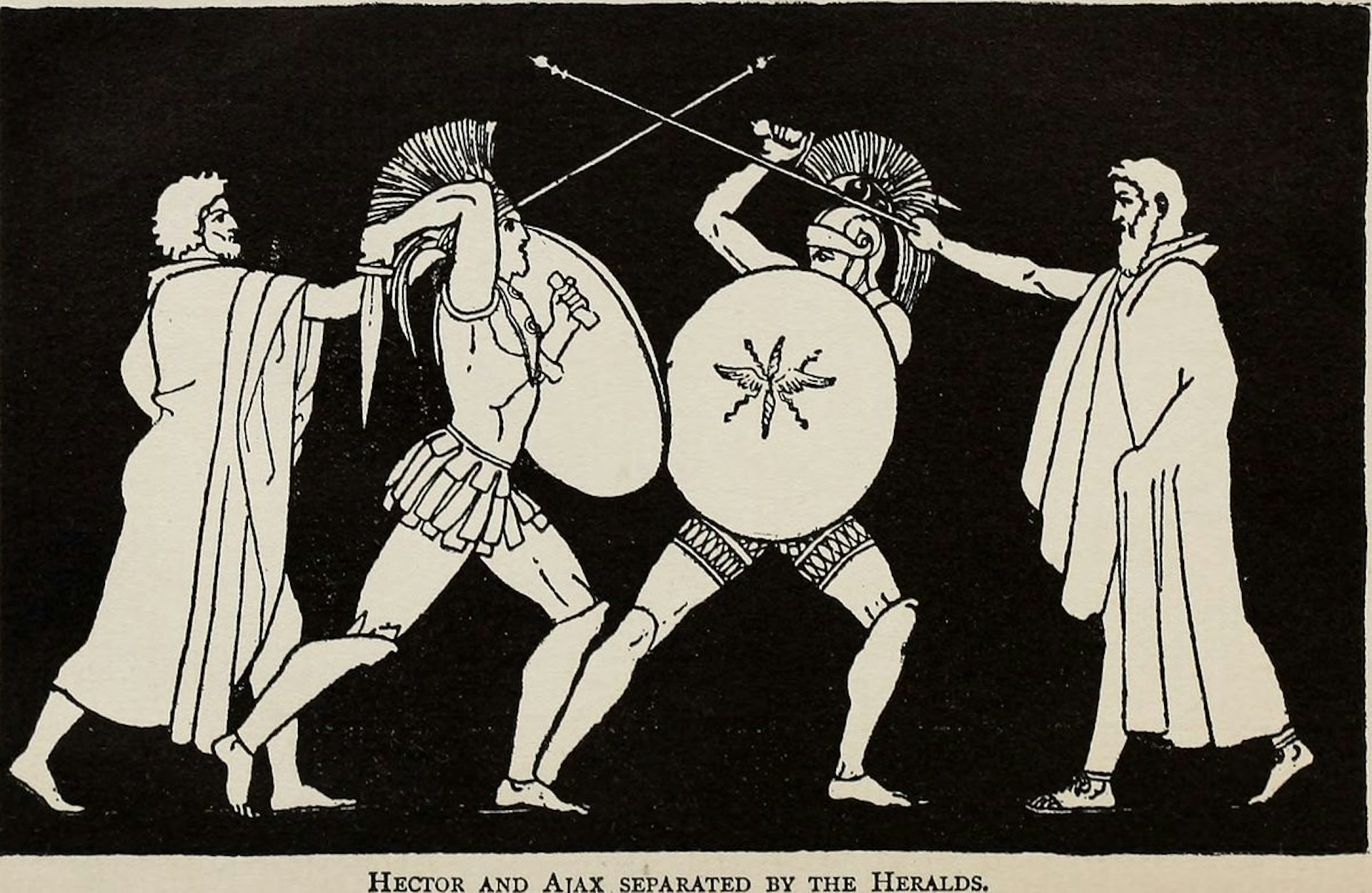

Hector and Ajax

The Greeks were understandably angry that Paris had fled from his duel. When a Trojan hit Menelaus with an arrow (wounding but not killing him), anger turned into an all-out battle. Hector, of course, led the Trojans and played a prominent part in the fighting.

Eventually, Hector decided to end the day’s battle by challenging any one of the Greek heroes to a duel. To decide who would face the fearsome Hector, the greatest Greek warriors drew lots; the task fell to Ajax the Greater, a hero known for his large size and impressive physical strength.

Hector Taking Leave of Andromache: The Fright of Astyanax by Benjamin West (1766).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThough Hector and Ajax fought long and hard, neither could gain the upper hand, and the two warriors were finally separated by heralds. Hector and Ajax exchanged gifts as a token of respect for one another’s skill. In the end, both armies called a truce and ceased fighting for the day.[16]

Illustration of Hector and Ajax being separated by the heralds after their duel by John Flaxman. From John Alfred Church, The Story of the Iliad (London: Macmillan 1911).

Internet Archive Book ImagesPublic DomainAttack on the Greek Camp

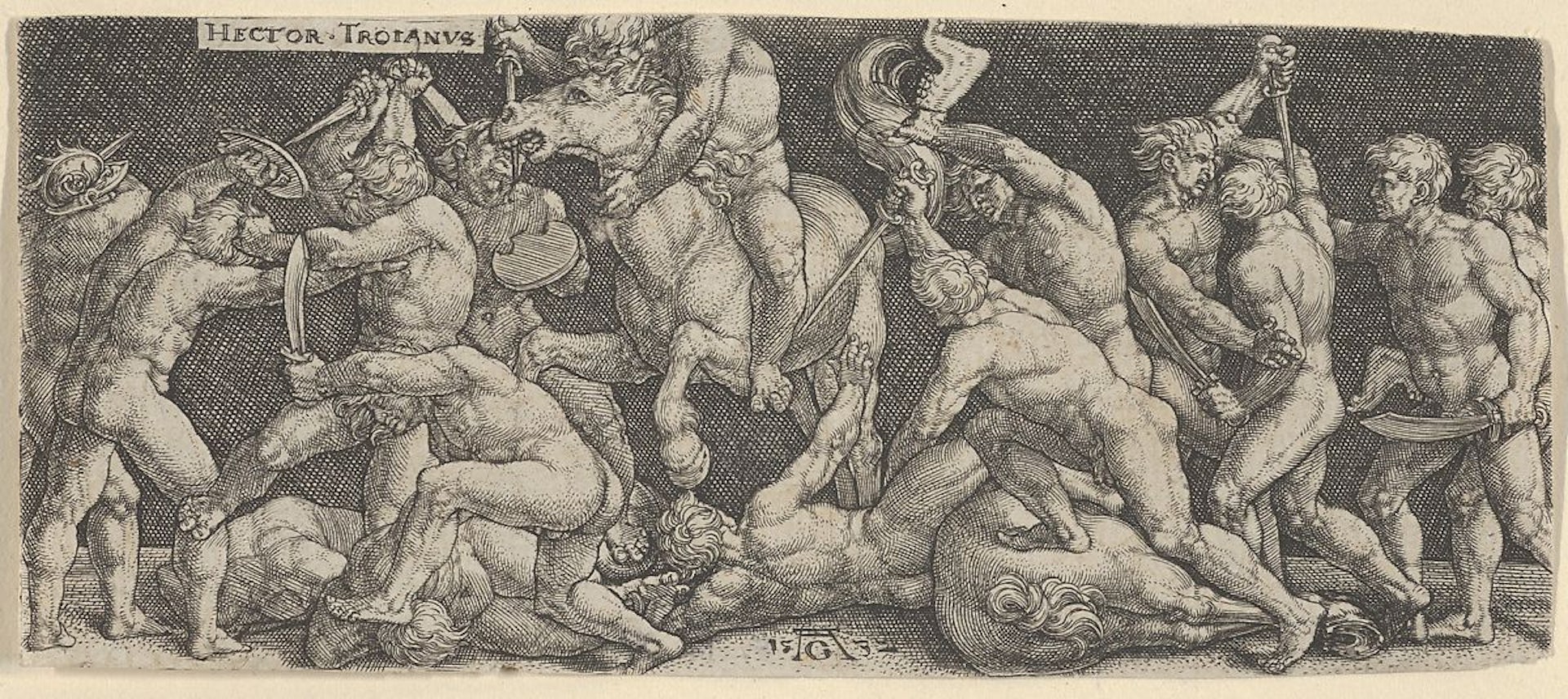

The next day, Hector was able to get the better of the Greeks and forced them to retreat to their camp on the beach. Because Achilles, the greatest of the Greek warriors, had left the fighting due to a quarrel with his commander, Agamemnon, the Greeks now had no one who could stand up to Hector. Knowing this, Hector resolved to drive the Greeks from Troy once and for all.[17]

In the following days, Hector continued to press the Greeks. At one point in the battle, Ajax threw a large stone at Hector and knocked him out, but Zeus ordered Apollo to revive the fallen prince.[18] He returned to battle stronger than ever, pushed past the fortifications of the Greek camp, and even started burning Greek ships.[19]

Hector Fighting the Greeks by Heinrich Aldegrever (1532).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Death of Patroclus

As the situation grew more desperate for the Greeks, Achilles’ closest friend, Patroclus, begged him to put aside his pride and help his friends. Achilles refused, but he agreed to let Patroclus put on his famous armor and lead his men, the Myrmidons, against Hector.

Clad in Achilles’ armor, Patroclus was able to strike fear into the hearts of the Trojans and drive them away from the Greek camp, back towards the city. Patroclus even went head-to-head with Hector, but Hector emerged victorious, killing the young warrior (with some help from Apollo).

Hector quickly realized that the man he had killed was not Achilles but instead Patroclus in his friend’s armor. After Hector had stripped the armor from the corpse, the Trojans and Greeks fought a vicious battle over the body. The Greeks barely managed to rescue it for a proper funeral.[20]

The Death of Hector

When Achilles found out that Hector had killed his best friend, he would stop at nothing to get revenge. Wearing a new suit of armor made for him by the smith god Hephaestus himself, he went back into battle and slaughtered numerous Trojans in search of Hector. All the Trojans fled before Achilles’ onslaught and retreated behind the walls of Troy—all except for Hector, who decided bravely (if foolishly) to stand his ground.[21]

When Hector’s parents saw their son preparing to do battle with the invincible Achilles, they begged him to come inside.[22] At first, Hector refused to listen and was determined to stand and fight honorably. But when he saw Achilles face-to-face, he lost heart and tried to run.

Achilles chased Hector three times around the walls of Troy. Finally, at the urging of Zeus, the goddess Athena (an ally of the Greeks) tricked Hector into fighting Achilles: she disguised herself as Deiphobus, one of Hector’s brothers, saying that they would stand against Achilles together.[23]

With renewed confidence, Hector stopped running and told Achilles he would face him. But he asked Achilles to swear that the winner would honor the loser with a proper funeral:

I will do unto thee no foul despite, if Zeus grant me strength to outstay thee, and I take thy life; but when I have stripped from thee thy glorious armour, Achilles, I will give thy dead body back to the Achaeans; and so too do thou.[24]

Achilles’ response was chilling:

As between lions and men there are no oaths of faith, nor do wolves and lambs have hearts of concord but are evil-minded continually one against the other, even so is it not possible for thee and me to be friends, neither shall there be oaths between us till one or the other shall have fallen, and glutted with his blood Ares, the warrior with tough shield of hide.[25]

The duel between Achilles and Hector was brief. Achilles threw his spear first, missing Hector; Hector then threw his spear, which bounced off Achilles’ shield. But according to Homer, Athena brought Achilles’ spear back to him and then vanished. Hector, deprived of both his spear and “Deiphobus,” realized that he was doomed. Achilles charged and speared Hector through the neck.

As Hector lay dying, he begged Achilles one last time to give his body to his parents for a proper funeral. When Achilles refused, he predicted Achilles’ own death at the hands of Paris and Apollo.[26]

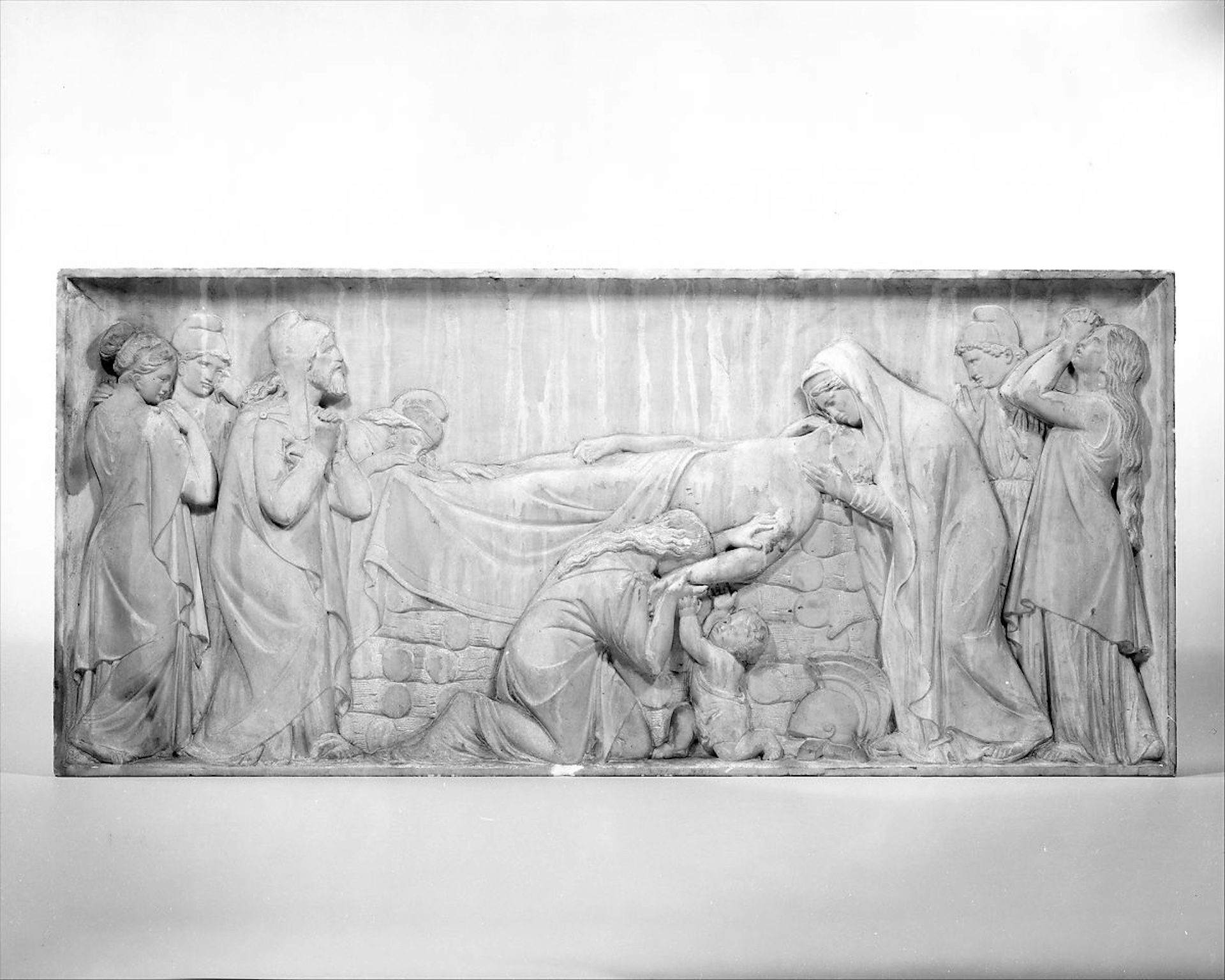

Hector’s Body

After Hector was dead, Achilles stripped him of his armor (the same armor Hector had stripped from the body of Patroclus the day before), tied him to the axle of his chariot, and dragged him three times around the walls of Troy. He then took the body back to his camp, where he continued to mistreat it; it was kept unblemished only through the intervention of Apollo.

The Corpse of Hector by Jacques-Louis David (1778). Fabre Museum, Montpellier, France.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFinally, after twelve days, Priam sneaked into the Greek camp to offer Achilles a ransom for the body of his favorite son. Reminded of his own aging father, Achilles took pity on Priam and complied.[27]

Hector Lying on his Funeral Pyre by Giovanni Maria Benzoni (19th century).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainPriam took the body back to Troy, where it was given a lavish funeral. Hector’s funeral marks the end of the Iliad, whose final words are: “On this wise held they funeral for horse-taming Hector.”[28]

Worship

As the greatest hero of Troy, Hector received worship at several sites through hero cult. Naturally, he had important cult centers in northwestern Asia Minor (modern Turkey), where Troy was said to have once stood.[29] Nearby, there was also apparently a sacred grove dedicated to Hector.[30]

Hector was also worshiped in parts of Greece. In one interesting local tradition, the people of the Greek city of Thebes were commanded by an oracle to bring Hector’s bones from Troy and enshrine them in a new tomb in their own land.[31] The presence of a tomb of Hector in Thebes suggests that he must have received divine honors there (this was the usual practice at the tombs of mythical heroes).

Pop Culture

Hector has continued to make appearances in pop culture. He is a character in numerous modern novels, including Colleen McCullough’s The Song of Troy (1998) and David Gemmell’s Troy series (2005–2007). He also appears in Eric Shanower’s Age of Bronze (1998–), an ongoing graphic novel series that retells the myth of the Trojan War.

Hector has also been portrayed in film and television, most notably in the 2004 film Troy, where he was played by Eric Bana. He is also a character in the 2003 miniseries Helen of Troy and in the 2018 series Troy: Fall of a City.

True to his ancient depiction, Hector has continued to be represented as a brave warrior, devoted to his family and city and noble to a fault. In medieval Europe, he was ranked among the so-called “Nine Worthies,” nine mythical and historical figures who were thought to best exemplify the ideals of chivalry (other “worthies” included the likes of Alexander the Great, the biblical David, and King Arthur).

But not all adaptations agree on Hector’s noble character: in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novel The Firebrand, for example, Hector is represented as a mean-spirited bully.