Nereids

Nereid Arranging her Necklace by Antoine-Louis Barye (ca. 1836)

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

Daughters of the sea gods Nereus and Doris, the Nereids were nymphs of the sea. Like other nymphs, they were represented as beautiful young women. Though they usually appeared as a group in Greek mythology, a handful of them—especially Amphitrite, Galatea, and Thetis—had their own individual myths.

From their home in the sea, the Nereids enjoyed a carefree existence in the company of other gods and sea creatures. Sometimes they came to the aid of heroes such as the Argonauts. Seen as kind, helpful goddesses, they were widely worshipped in Greek popular religion.

Etymology

The term “Nereid” (Greek Νηρηΐς, translit. Nērēḯs; pl. Nereids, Greek Νηρηΐδες, translit. Nērēḯdes) was traditionally said to have been derived from the name of the Nereids’ father, Nereus (Greek Νηρεύς, translit. Nēreús).

However, since Nereus’ only significant act in Greek mythology was fathering the Nereids, it is likely that the term “Nereid” is actually older than the name “Nereus.” If this is the case, then the etymology of the term is obscure; it may be related to the rare Greek words νῆρις (nêris, “hollow rock”) and νηρός (nērós, “low-lying”), but the origin is likely pre-Greek.[1]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Nereid, Nereids Νηρηΐς (Nērēḯs), Νηρηΐδες (Nērēḯdes) Phonetic

IPA

[NEER-ee-id, NEER-ee-idz] /ˈnɪər i ɪd, ˈnɪər i ɪdz/

Titles and Epithets

Ancient authors gave the Nereids various epithets, most of them emphasizing their beauty. Some examples include ἀγακλειτός (agakleitós, “renowned”), ἐρόεσσα (eróessa, “lovely”), εὐειδής (eueidḗs, “beautiful”), εὐπλόκαμος (euplókamos, “fair-haired”), ῥοδόπηχυς (rhodópēchys, “rosy-armed”), and χαρίεσσα (charíessa, “graceful”).

Attributes

General

Like other nymphs, the Nereids were imagined as beautiful young women—exceptionally beautiful, in fact. In one famous myth, the African queen Cassiopeia got into trouble for boasting that she (or, in some versions, her daughter Andromeda) was even more beautiful than the Nereids (see below). Some later authors further developed the Nereids’ attributes by representing them with green or sea-colored hair.[2]

In addition to their beauty, the Nereids were sometimes said to possess the gift of prophecy, a power they shared with their father Nereus. They were mostly represented as helpful and kind goddesses, though they could sometimes be vengeful.

Unlike some other nymphs, such as the Dryads and Hamadryads—who had an extraordinarily long lifespan, but were not immortal—the Nereids appear to have been immune to death.

The Nereids lived with their father Nereus in a grotto on the bottom of the sea.[3] From this luxurious home, they wandered the seas, amusing themselves by singing, dancing, and playing in the waves or on the beach.[4] They were often accompanied by other gods or sea creatures, like dolphins or tritons.[5]

A Nereid riding a triton, from the southwest medallion of the Deities Mosaic (2nd century CE)

Villa of Orbe-Boscéaz, Vaun / Mary HarrschCC BY-SA 4.0Iconography

In ancient art, as in literature, the Nereids were shown as beautiful young women; from the fourth century BCE on, it was common to represent them as scantily clothed or even completely nude. In rare cases, they were given fish tails—similar to modern mermaids.[6]

Various attributes and motifs helped to distinguish the Nereids from other divinities. They were often shown riding through the sea on sea creatures or in the company of gods such as Poseidon or Aphrodite. Some artists depicted them with fish in their hands to emphasize their connection with the sea. Nereids also appeared in artistic depictions of certain mythological scenes—for example, Heracles’ wrestling match with Nereus or episodes from the life of Achilles.

Nereids were often featured in ancient vase paintings, but were also popular in sculpture and in Roman mosaics and sarcophagi.[7]

Family

The Nereids were the daughters of Nereus, the “Old Man of the Sea,” and his wife Doris, one of the Oceanids.[8] One obscure source, however, made Amphitrite (usually a Nereid herself) the mother of the Nereids.[9]

Traditionally, there were fifty Nereids,[10] though in one source we hear of one hundred.[11]

Relief sculpture of Nereus, the father of the Nereids, from the Pergamon Altar (2nd century BCE)

Pergamon Museum, Berlin / Miguel Hermoso CuestaCC BY-SA 4.0According to Aelian, the Nereids had a brother named Nerites, who was a handsome companion of Poseidon.[12]

A handful of the Nereids took consorts and gave birth to important children. Thetis, for example, married the mortal hero Peleus and became the mother of the great Achilles; Amphitrite married Poseidon, the Olympian god of the sea, and became the mother of Triton and Rhode (among others); Psamathe was the mother of Phocus (by Aeacus) and of Theoclymenus and Theonoe[13] (by Proteus); and so on.

Mythology

The Nereids and the Gods

The Nereids enjoyed a proud pedigree. Their father was Nereus, the revered “Old Man of the Sea,” who was himself the son of the primordial gods Gaia and Pontus—the embodiments of the earth and the sea, respectively. Their mother was Doris, daughter of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys and thus one of the three thousand goddesses known as the Oceanids.

The Nereids were highly honored among the gods. It is no surprise, then, that the Nereid Amphitrite became the queen of no less a god than Poseidon, one of the elder Olympians and ruler of the seas.[14] Thetis, another Nereid, was courted relentlessly by both Zeus and Poseidon, though neither god was able to win her over.[15]

For the most part, the Nereids were represented as staunch supporters of the Olympian regime—and, above all, of Zeus’ kingship. In one myth, it was Thetis who rescued Zeus (with the help of the hundred-handed Briareus) when the other Olympian gods attempted to overthrow him.[16] In another myth, the Nereids cared for Hephaestus when he was cast from Olympus by his mother Hera.[17] Finally, in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca (a vast epic from late antiquity), the Nereids help the young Olympian god Dionysus during his war against the Indians.[18]

Illustration by John Flaxman (1795) of a myth recounted in Book 1 of Homer's Iliad: Briareus is summoned by Thetis to help Zeus when the other Olympians try to overthrow him

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe Nereids and Mortals

The Nereids also appeared in a number of myths involving heroes and mortals.

The Argonauts

When Jason led the Argonauts back home after stealing the Golden Fleece, one of the most daunting dangers they faced was the Planctae, or Wandering Rocks; these were large rocks that were dangerous to sailors due to their smoothness and the surging waves that rose up around them.

According to Apollonius of Rhodes, it was the Nereids—obeying Hera’s orders—who helped push the Argonauts through the Planctae:

Hereupon on this side and on that the daughters of Nereus met them; and behind, lady Thetis set her hand to the rudder-blade, to guide them amid the Wandering rocks. And as when in fair weather herds of dolphins come up from the depths and sport in circles round a ship as it speeds along, now seen in front, now behind, now again at the side and delight comes to the sailors; so the Nereids darted upward and circled in their ranks round the ship Argo, while Thetis guided its course. And when they were about to touch the Wandering rocks, straightway they raised the edge of their garments over their snow-white knees, and aloft, on the very rocks and where the waves broke, they hurried along on this side and on that apart from one another. And the ship was raised aloft as the current smote her, and all around the furious wave mounting up broke over the rocks, which at one time touched the sky like towering crags, at another, down in the depths, were fixed fast at the bottom of the sea and the fierce waves poured over them in floods. And the Nereids, even as maidens near some sandy beach roll their garments up to their waists out of their way and sport with a shapely-rounded ball; then they catch it one from another and send it high into the air; and it never touches the ground; so they in turn one from another sent the ship through the air over the waves, as it sped on ever away from the rocks; and round them the water spouted and foamed… And as long as the space of a day is lengthened out in springtime, so long a time did they toil, heaving the ship between the loud-echoing rocks; then again the heroes caught the wind and sped onward…[19]

Achilles

Through Thetis—herself one of the most famous of the Nereids—the Nereids were closely connected with the mythology of Achilles.

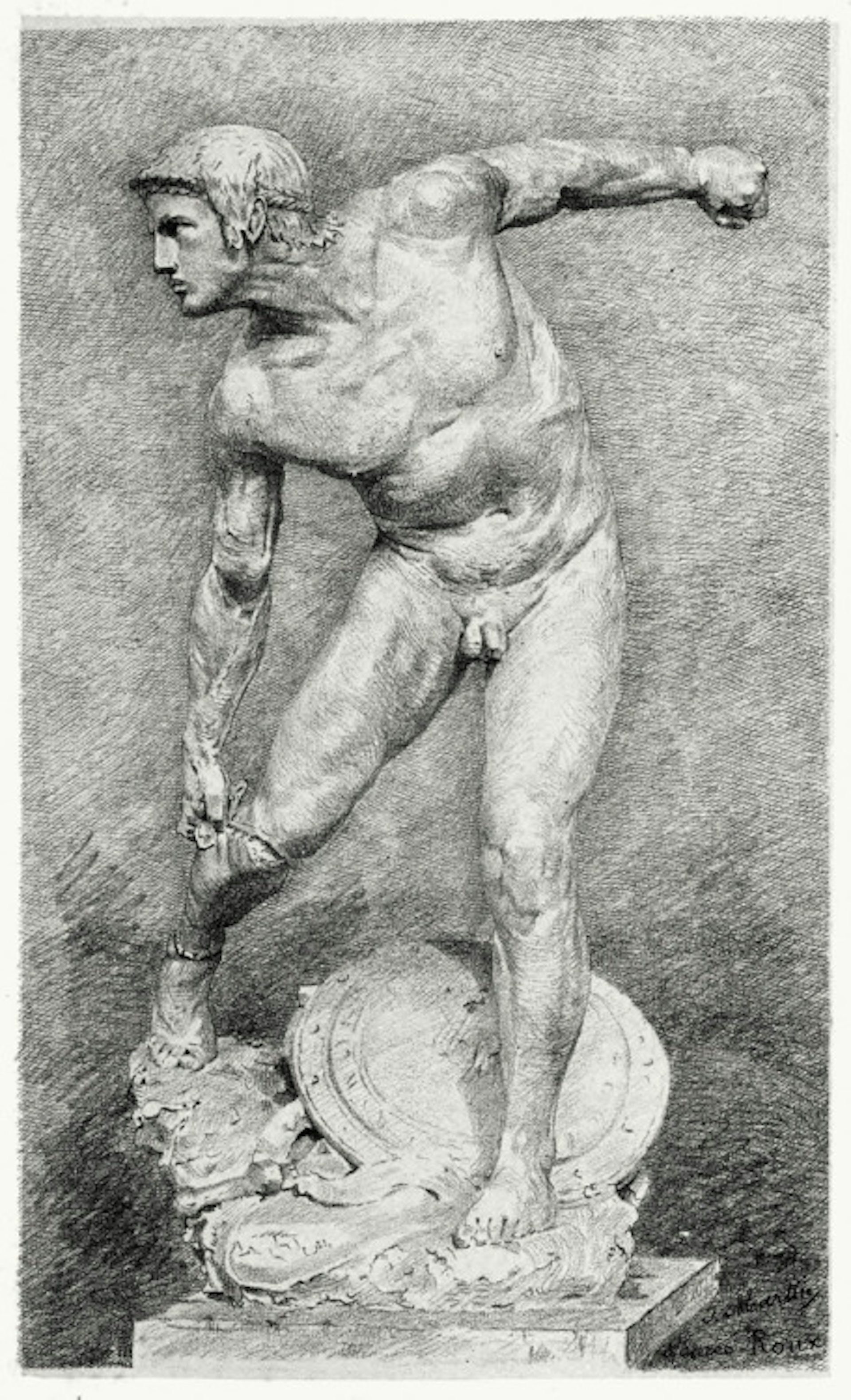

Lithograph showing Achilles putting on the armor brought to him by his mother, the Nereid Thetis, by J. Martin after a sculpture by C. A. Roux (1894)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainWhen the Nereid Thetis married the mortal hero Peleus, all the other Nereids were guests at her lavish wedding.[20] Later, when Thetis’ son Achilles traveled to Troy to fight alongside the other Greeks, he was escorted by the Nereids.[21] When Achilles mourned the death of his companion Patroclus, who had been killed in battle by the Trojan hero Hector, Thetis and the Nereids came to Troy to comfort him and grieve with him, as well as to deliver a new suit of armor (since Hector had stripped the original armor from Patroclus’ corpse).[22] Finally, the Nereids joined Thetis in mourning Achilles when he too was ultimately killed in battle.[23]

Others

The Nereids make an appearance in the myth of Theseus, the most famous of the Athenian heroes. In one tradition, Amphitrite and the Nereids helped Theseus retrieve a ring that the Cretan king Minos had cast into the sea, thus helping him prove that he was the son of Poseidon.[24]

Another myth connected the Nereids with Ino, a princess of Thebes who was driven mad by Hera as punishment for nursing Dionysus.[25] According to the Roman poet Ovid, when the mad Ino leapt into the sea with her son Melicertes, the Nereids transformed both Ino and Melicertes into gods (renaming them Leucothea and Palaemon, respectively).[26]

The Nereids sometimes briefly appeared in accounts of Heracles’ wrestling match with their father Nereus. When Heracles was sent to fetch the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides for his eleventh labor (or twelfth, in some versions), he went to the wise Nereus to ask for the garden’s location. But Nereus would not reveal the secret to Heracles until he had defeated him in a wrestling match (during which Nereus changed himself into various monstrous shapes). Some artistic renderings show the Nereids looking on during this scene.[27]

In most of their myths, the Nereids were benevolent and helpful deities. But they could also be cruel in their anger, just like other gods. In one myth, the haughty queen Cassiopeia dared to boast that she (or, in some traditions, her daughter Andromeda) was more beautiful even than the Nereids. Offended, the Nereids complained to the sea god Poseidon, who punished Cassiopeia by laying waste to her husband’s kingdom and commanding her to sacrifice her daughter Andromeda.[28]

Important Nereids: Amphitrite, Galatea, Thetis, and Others

Though the Nereids often appeared in Greek mythology as a group, only a few of them had any individual mythology of their own. The most important of these were Amphitrite, Galatea, and Thetis.

Amphitrite

Amphitrite—listed among the Nereids by Hesiod, but described by some authorities as an Oceanid instead—was the wife of Poseidon and thus the queen of the sea. When Poseidon first fell in love with her, Amphitrite hid from him in the depths of the sea. She was eventually found by a dolphin, who pleaded Poseidon’s case so persuasively that Amphitrite agreed to the marriage.

Amphitrite by François Théodore Devaulx (1866). North façade of the Cour Carrée in the Louvre Palace.

JastrowCC BY 2.5Amphitrite gave Poseidon a son, the merman Triton, as well as several daughters, including Benthesicyme (the embodiment of the depths of the sea) and Rhode (the nymph from whom the island of Rhodes got its name).[29]

Galatea

The mythology of the Nereid Galatea is set around the island of Sicily. Galatea loved the handsome young Acis, son of the native Italian god Faunus. But Acis had a rival in the hideous Cyclops Polyphemus—the same Cyclops who terrorized Odysseus and his crew on their way home from Troy. Polyphemus loved Galatea desperately, even though she did not return his affections.

One day, Polyphemus found Galatea and Acis lying in each other’s arms. He flew into a jealous rage and hurled a massive rock at them. Galatea managed to escape, but Acis was crushed and killed. Heartbroken, she transformed Acis into a river. In some versions, however, Polyphemus was able to win over Galatea in the end and make her his wife.[30]

Triumph of Galatea by Raphael (ca. 1512)

Villa Farnesina, RomePublic DomainThetis

Probably the most famous of the Nereids was Thetis, the wife of Peleus and the mother of Achilles. Her beauty won her the unwanted attention of the amorous Zeus (or, in some versions, both Zeus and Poseidon). But Thetis did not become Zeus’ lover in the end—either because she did not want to offend Zeus’ wife Hera, or because of a prophecy that Thetis would bear a son destined to be more powerful than his father (a decidedly terrifying prospect for the gods, who were always afraid of being overthrown by their sons).

Thetis was therefore married off to the mortal hero Peleus, who first had to capture Thetis by holding on to her as she changed into different shapes. The couple had a magnificent wedding, attended by the gods themselves.

Soon after, Thetis gave birth to a son: the great warrior Achilles. In some traditions, Thetis tried to make the infant Achilles immortal and abandoned Peleus when the attempt failed. While Achilles was fighting in the Trojan War, Thetis often came to help and comfort him, speaking to Zeus on his behalf when he was insulted by Agamemnon and later bringing him a new suit of armor forged by the smith god Hephaestus.

Thetis appeared in a handful of other myths, too. For example, she helped Zeus defeat an uprising of the other Olympian gods; she cared for Hephaestus when he was thrown down from the heavens; and she led the other Nereids in guiding the Argonauts through the Planctae.[31]

Other Nereids

A few other Nereids also played a small individual role in Greek mythology, though they are not quite as important as Amphitrite, Galatea, or Thetis.

One Nereid, Psamathe, had two important consorts. The first was Aeacus, the king of Aegina. With him she had a son named Phocus, who was ultimately murdered by his half-brothers, Peleus and Telamon (Aeacus’ sons by another wife). With her second consort, the sea god (or Egyptian king) Proteus, Psamathe had a prophetic daughter named either Eido, Eidothea, or Theonoe, as well as a son named Theoclymenus.[32]

Certain mythological figures usually described simply as “nymphs” were occasionally listed as Nereids by less traditional sources. For example, Arethusa—catalogued as a Nereid by Hyginus—is the name of several water nymphs, the most famous of whom was transformed into a subterranean stream to escape being raped by the river god Alpheus. Dione (the mother of Aphrodite in some traditions) and Orithyia (a princess carried off by Boreas, the god of the north wind) were also sometimes listed as Nereids.

However, the status of “Nereids” such as Arethusa, Dione, and Orithyia is unclear. It is possible that the sources that listed them as Nereids were challenging more traditional genealogies. But it is also possible that these were completely different individuals from the more famous characters whose names they happened to share. Alternatively, the sources may have simply been mistaken.

Worship

The Nereids were very important in ancient “popular” religion. Sailors, for example, prayed to the Nereids for safe voyages or for rescue from disasters at sea.[33]

The Nereids had their own cult sites in a few locations throughout Greece.[34] There is evidence that they were sometimes worshipped together with their father Nereus.[35] Since the Nereids had the gift of prophecy, they also had an oracle on Delos, which they shared with the minor sea god Glaucus.[36]

Worship of the Nereids seems to have extended beyond Greece, too. According to the historian Herodotus, the Persians made offerings to Thetis and the Nereids when their ships were brutalized by a three-day storm during their invasion of Greece.[37] Alexander the Great sacrificed to them during his campaign of world conquest.[38] Nereids were also popular in Roman art, especially on sarcophagi (suggesting that they may have been somehow associated with death and the passage of souls to the afterlife).

Pop Culture

Though Nereids experienced a revival in cultural importance during the Renaissance, frequently appearing in art of that era, they are not usually encountered in modern pop culture. Nereids are, however, very important in modern Greece, where they are famous for their beauty, play a major role in folklore, and are believed to prophesy the future.