Hephaestus

Vulcan Forging the Thunderbolts of Jupiter by Peter Paul Rubens (between ca. 1636 and 1638)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainOverview

Hephaestus was one of the Twelve Olympians and the god of fire and the forge. Though lame from birth, he was a master craftsman, fashioning magnificent weapons, talismen, machines, and buildings for gods and mortals alike.

The crippled Hephaestus was always something of an outsider. He was married to the beautiful Aphrodite, goddess of love, though she took many illicit lovers (among them the war god Ares). While Olympus was usually named as Hephaestus’ home, the god was most closely associated with the islands of Lemnos and Sicily—the sites of his mythical workshops.

Key Facts

What were Hephaestus’ attributes?

Hephaestus was usually imagined as a heavily muscled and bearded figure. He was famously lame, and some sources represented him as rather unattractive, in contrast to the other Olympian gods. He tended to be shown with smithing tools in hand, such as a hammer, ax, or tongs.

Vulcan Forging the Thunderbolts of Jupiter by Peter Paul Rubens (between ca. 1636 and 1638)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainHow was Hephaestus worshipped?

Hephaestus was not worshipped as extensively as some of the other Olympians. He did, however, have important cults in Athens (where he was one of the city’s patron gods) and on the island of Lemnos.

Like the other Olympians, Hephaestus was worshipped with sanctuaries, offerings, and festivals. The temples at his cult centers of Athens and Lemnos were especially impressive, though Hephaestus had sanctuaries elsewhere in the Greek world, too.

Photo of the Temple of Hephaestus at Acragas (modern Agrigento)

ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0Hephaestus’ Exile from Olympus

The lame Hephaestus lacked the physical perfection associated with the other major Greek gods. Because of this, he was often mistreated, ridiculed, or rejected by his fellow deities. In one myth, his mother Hera was so disgusted by his misshapen appearance that she cast him from Olympus as soon as he was born (though in other traditions, it was Zeus who exiled Hephaestus).

Hephaestus eventually came back home—where, according to some accounts, he took revenge on his mother by building a chair that trapped her as soon as she sat in it. Understandably, it took a great deal of effort to persuade Hephaestus to release Hera.

Zeus with Hera Expelling Hephaestus by Gaetano Gandolfi (1761–1769)

National TrustPublic DomainEtymology

As with many Greek deities, there is no reliable etymology for the name “Hephaestus.” The first known recording of the name (or a form of it) is in an inscription on the palace at Knossos on Crete, where it appears as a-pa-i-ti-jo in the syllabic Linear B script used in Bronze Age Greece (ca. 1600–1100 BCE).

The palace at Knossos was a relic of the Minoan people who lived more than a thousand years before the Greek classical period (490–323 BCE), indicating that the word was present in early Greek society. However, scholars have generally interpreted the name that appears on this inscription as theophoric—that is, as a name that contains the name of the god, rather than the name of the god itself (similar to later Greek names such as Hephaestion).[1]

Today, the etymology of Hephaestus’ name is usually thought to have been pre-Greek.[2]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Hephaestus Ἥφαιστος Phonetic

IPA

[hi-FES-tuhs] /hɪˈfɛs təs/

Other Names

Epithets

Many of Hephaestus’ epithets referred to his physical appearance or his lameness, such as amphigyeis (“the lame one”) and kyllopodiōn (“foot-dragging”). Other epithets were more positive, emphasizing Hephaestus’ skills as a craftsman and smith. These epithets included klytotechnēs (“famous artificer”), polymētis (“shrewd”), and chalkeus (“bronze-working”).

Attributes

Domains

Hephaestus was the god of crafts of all kinds, especially metalworking. He was also the god of fire, and his workshop was said to be located (appropriately) beneath a volcano.

Iconography

Hephaestus was usually depicted as a burly man, either bearded or unbearded. Due to his lameness, he lacked the physical perfection of the other Olympians, and there are artistic representations that call attention to his crippled legs. In art, Hephaestus was generally dressed simply, in a tunic and a cap called a pilos. He was distinguished by his attributes, the tools of his trade: an ax, double hammer, tongs, bellows, and firebrands.

This late 16th century Italian statue depicts a crippled Hephaestus (Vulcan was his Roman name) at the forge, as is indicated by the anvil and what appears to have been a blacksmith’s hammer in his right hand. Hephaestus was rarely depicted in statuary form in the ancient world.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThough somewhat removed from the other gods, Hephaestus did have an entourage of his own, consisting of the giant, one-eyed Cyclopes, who served as his helpers at his workshop. The god was sometimes also shown riding atop a donkey.

Family

Family Tree

Mythology

Birth and Expulsion

A central aspect of the Hephaestus mythos—and one often depicted in both ancient and modern art—was his expulsion from Olympus, as well as his eventual return. This story saw two main variations:

After Hephaestus was born, his mother, Hera, was disgusted when she found out that the child had a malformed foot. Deeming Hephaestus unworthy of divinity, Hera threw him down to earth. After his fall, however, Hephaestus was discovered by the Nereid Thetis and some of her sisters, who kindly nursed him back to health.[9]

In another story, it was Zeus who cast Hephaestus out of heaven because the lame god had tried to come to his mother’s assistance after she angered Zeus. Hephaestus fell for a full day before landing on the island of Lemnos (this spot, the “Lemnian earth,” became a sacred site for pilgrims of Hephaestus, who claimed that it possessed healing powers). This time, it was the Sintian people who helped Hephaestus.[10]

These may or may not have been multiple variants of a single myth. Both of them, interestingly, feature in Homer’s Iliad: there, the first fall is said to have taken place right after Hephaestus was born, while the second took place when he was already fully grown.

Yet some sources combine the versions, or make them into mutually incompatible alternatives: the mythographer Apollodorus, for example, writes that Hephaestus was cast out of heaven by Zeus for trying to help his mother, Hera (as in the second account) and that he was saved by Thetis (as in the first account). He then goes on to say that Hephaestus only became crippled as a result of his fall; this would imply that the first fall of Hephaestus—when he was thrown out of heaven because of his lame, malformed feet—could not have happened.[11]

The Return of Hephaestus

Either way, Hephaestus was understandably troubled by the incident and refused to return to Olympus. To avenge himself (based on the first account), Hephaestus built a trap for Hera—a chair with a secret mechanism. Once Hera sat on the chair, it locked her in place.

For some time, Hephaestus wandered the earth and refused to release Hera from the chair. He eventually returned to his proper place on Olympus, albeit not by his own volition. According to most stories, Hephaestus was wined by Dionysus, who gave him enough of his vineyard’s finest to ensure that he slept soundly; once Hephaestus was resting peacefully, the wine god placed him on a donkey that carried him to the top of Mount Olympus. Once there, he finally consented to release his mother and forgive her.[12]

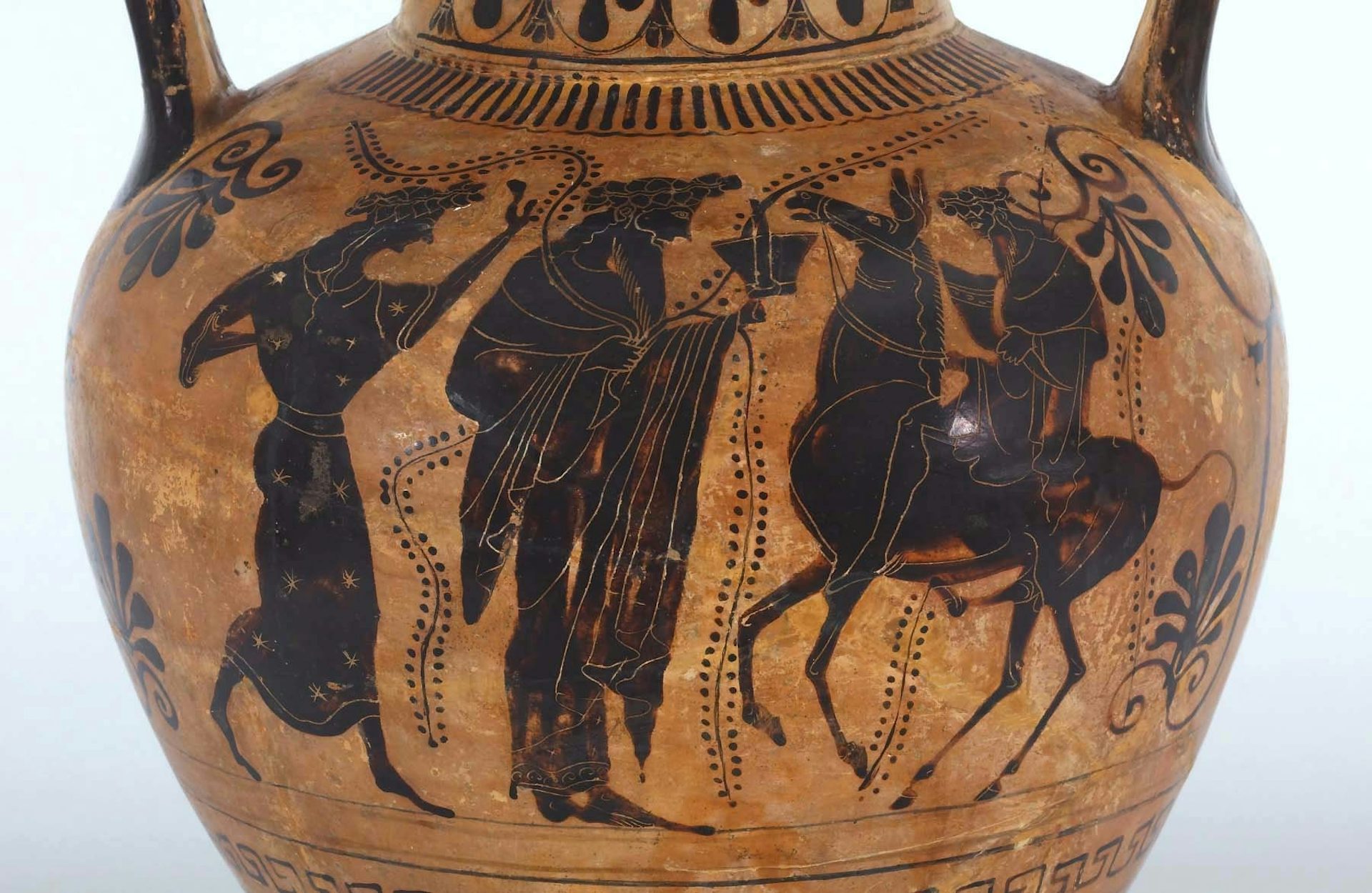

The lame Hephaestus appears on a donkey with Dionysus as the central figure of this vase painting attributed to the circle of the Antimenes Painter (ca. 520 BCE). This famous and comedic scene was depicted often on pottery made in Attica and Corinth.

Walters Art MuseumCC0In other traditions, however, Hephaestus trapped Hera on the chair because, having been cast out of Olympus as an infant, he did not know who his parents were. As soon as Hera revealed that she was his mother, Hephaestus let her go.[13]

Hephaestus, the Craftsman

Hephaestus was not usually the center of myths; he seldom figured as the hero in dramatic tales, took fewer lovers than his brothers and sisters, and was less conspicuous overall. Unlike most of the other gods, he was often a ridiculous or comedic figure, in part because of his disability.

But Hephaestus was not to be underestimated. He was cunning and vengeful, often earning small victories. Such triumphs came from his tremendous skill as an artisan and his ability to contrive clever traps and tricks. Hephaestus’ masterful skill and ingenuity resulted in the creation of almost everything unique or sophisticated in Greek mythology.

Hephaestus ran a massive workshop on Mount Olympus, complete with twenty bellows, a forge, and an anvil. Hephaestus also boasted a retinue of assistants, including not only several Cyclopes but also automata, which the clever god had crafted himself. Homer described these marvelous creations in the Iliad as “handmaidens wrought of gold in the semblance of living maids. In them is understanding in their hearts, and in them speech and strength, and they know cunning handiwork by gift of the immortal gods.”[14]

In later traditions, Hephaestus also had workshops in other, even more exotic locations. Some sources, for example, placed Hephaestus’ workshop at or near the volcanic Mount Etna in Sicily.[15] Others placed the workshop on the island of Lemnos, said to be especially sacred to Hephaestus.[16]

Hephaestus fashioned countless beautiful things for gods, kings, and heroes, including palaces, temples, statues, armor and weapons, and jewelry. Among his most famous creations were aegis (the mighty shield used by Zeus and Athena);[17] the necklace of Harmonia, sometimes said to curse whoever wore it (this was Hephaestus’ revenge on his wife, Aphrodite, who produced Harmonia through her adulterous affair with Ares);[18] and the armor of various heroes, including Heracles,[19] Achilles,[20] and Aeneas.[21]

Aphrodite and Ares

Hephaestus married Aphrodite, the most beautiful of all the goddesses, but their marriage was an unhappy one. In a famous scene from the Odyssey, a blind poet named Demodocus sings of how Hephaestus discovered that his wife was having an affair with Ares, the god of war.

Hephaestus, the story goes, hatched a plan to catch Aphrodite and Ares in the act. He went to his workshop and created a net so fine that it could not be seen by the naked eye. He then placed the net over his bed; when Aphrodite and Ares, thinking Hephaestus was away, went to Hephaestus’ bed to have sex, Hephaestus trapped them in the net and called all the gods over to look upon the ridiculous scene.

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan by Joachim Wtewael (1604–1608).

J. Paul Getty MuseumPublic Domain“Soon shall both lose their desire to sleep,” says Homer’s Hephaestus, complaining about his cheating wife, “but the snare and the bonds shall hold them until her father pays back to me all the gifts of wooing that I gave him for the sake of his shameless girl; for his daughter is fair but bridles not her passion.”[22]

All the gods laughed heartily at the scene—all except Poseidon, the god of the sea, who insisted that Hephaestus let Ares and Aphrodite go. Hephaestus finally agreed; released from Hephaestus’ adamantine net, Ares and Aphrodite both fled the scene, ashamed.[23]

With this colorful depiction of their relationship in mind, it was unsurprising that Hephaestus and Aphrodite had no children together.

Athena and Athens

In another important myth, Hephaestus played a key role in the foundation of Athens. It began when Hephaestus first took an interest in Athena. Hephaestus and Athena, incidentally, were often viewed as counterpart deities. Both were creators and benefactors who brought the gifts of wisdom, creativity, and craft to humankind.

According to one version of the story, Hephaestus attempted to rape Athena, but she eluded him just as he was about to consummate the act, causing him to ejaculate on the ground. His spilled semen impregnated Gaia, and out of the earth sprang Erichthonius, a prince raised by Athena who would become an early ruler of Athens.[24]

This 19th century lithograph of ancient Greek pottery design shows the birth of Erichthonius. Hephaestus, holding the tongs of a blacksmith, stands behind Gaia as she presents Erichthonius to Athena.

New York Public LibraryPublic DomainIn another (less familiar) version, Hephaestus earned Athena’s hand in marriage because he had, in a sense, helped to deliver her; he had done so by splitting Zeus’ head open as she began to emerge from it. While Zeus gave his blessing to Hephaestus, Athena remained reluctant. In the marriage bed, when Hephaestus was about to consummate the marriage, Athena lost her nerve and fled, causing Hephaestus to ejaculate upon the earth. In this version as well, Hephaestus’ spilled seed gave rise to Erichthonius.[25]

Whatever the exact details, Hephaestus’ child Erichthonius went on to become one of the founding figures of the great city of Athens. Like many children born from the earth, Erichthonius was sometimes depicted as having serpent features, though he was still regarded as a great king and the ancestor of the Athenian people.

Hephaestus and the Trojan War

According to the Iliad, it was Hephaestus who made Achilles a new set of armor when his previous set was stripped from the corpse of Patroclus by the Trojan hero Hector. (Achilles’ friend Patroclus had donned the awe-inspiring armor in a fatal effort to scare the Trojans away from the Greek camp.) The shield was particularly magnificent, decorated with elaborate scenes illustrating every facet of human life; it is described in detail by Homer.[26]

Later, Hephaestus helped Achilles fight off the river god Scamander. Achilles was on a rampage, killing countless Trojan warriors and throwing their corpses into the Scamander River. The river god, choking on bodies and blood, tried to drown Achilles in his rushing waters. The great hero might have perished then and there if Hera had not sent Hephaestus to help him. Hephaestus threatened to scorch Scamander and his river with fire if he did not leave Achilles alone; Scamander immediately did as he was asked.[27]

Other Myths

Hephaestus featured in a handful of other myths. In the terrible war between the Olympian gods and the so-called Giants (monsters born to the primordial earth goddess Gaia), Hephaestus killed the Giant called Mimas.[28]

In another important (and deeply misogynistic) myth—recounted by Hesiod in two different poems[29]—Zeus sought to punish humanity for the theft of fire by presenting them with the first woman. This woman was designed to unleash every conceivable evil on humanity and was, ironically, named Pandora (“all-gifted”). Naturally, it was the skilled craftsman Hephaestus who was tasked with creating Pandora.

Worship

Festivals

The most well-known ancient festivals of Hephaestus were celebrated in Athens, where, as the father of the founding hero Erichthonius, he was especially revered. The Hephaestia, celebrated every four years, involved a torch race and sacrifices to the god.[30] In another festival, the Chalkeia, craftsmen walked in a procession through the city in honor of Hephaestus and his counterpart Athena.[31]

In different parts of the Greek world, Hephaestus was also connected with the mystery cult of the Cabiri (whom he was said to have fathered).[32] These mysteries most likely involved initiation rites, feasting, and sacrifices; they were practiced primarily in Asia Minor, Macedonia, Boeotia, and some northeastern Aegean islands.

Temples

The public cult of Hephaestus was not as widespread in Greece as that of most of the other Olympians. Hephaestus did, however, have important cult centers at Lemnos, an Aegean island that was especially sacred to him, and Athens, where he was worshipped together with Athena as one of the city’s chief patron gods.

The Temple of Hephaestus, sometimes erroneously called the Theseum, in the agora of Athens.

Maria Drimona / PixabayPublic DomainAt Lemnos, the spot where Hephaestus supposedly landed when he was thrown from heaven was an especially sacred site. It was believed that this spot could cure various ailments, including snake bites.[33]

There was a large temple of Hephaestus, called the Theseium, near the agora of Athens; in it, the cult statue of Hephaestus stood next to that of Athena.[34]

Hephaestus also had a handful of temples in Sicily, where he was sometimes said to have had a workshop.

Pop Culture

Hephaestus has enjoyed a lively presence in popular media. In films and television based on Greek mythology, he usually appears as a powerful, thick-armed craftsman in the archetypal blacksmith mode. In the 1981 film Clash of the Titans, he was played by the large British wrestler Pat Roach. In the television series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess, meanwhile, he appeared as a large, leather-clad blacksmith played by actors Julian Garner and James Hoyte.

In video games, too, Hephaestus is a renowned crafter of items. In the God of War series, he makes weapons for the protagonist, Kratos. In the classic video game Diablo II, a crazed blacksmith and dungeon master is named Hephaesto in a clear homage to the Greek deity.

Finally, Hephaestus plays a role in the popular Percy Jackson and the Olympians book series by Rick Riordan—a series that has reignited interest in Greek mythology. In the fourth book, The Battle of the Labyrinth, Hephaestus appears as the master of the kiln, with a workshop that pumps out finely-tuned objects. Because the novel is a modern retelling, however, his most notable act is repairing an old Toyota that had broken down.