Vulcan

Overview

The master of metallurgy and handicraft, Vulcan was the Roman god of fire and forge, as well as the patron of artisans and smiths. Known as the ugliest of the gods, Vulcan suffered from lameness in one leg due to an injury he sustained as a child. The patron of craftsmen was exceedingly crafty himself and used his guile to marry Venus, the goddess of love and sexual desire. As with many Roman deities, Vulcan was a near identical copy of his Greek equivalent: Hephaestus.

A storied member of the Roman pantheon, Vulcan was originally adapted from an Etruscan deity known as Sethlans. This version of Vulcan was later Hellenized and given most of the trappings of Hephaestus; Vulcan’s mythological tradition was largely similar to that of his Greek counterpart.

In this bronze statue from the first century CE, a bearded Vulcan readies himself for the rigors of the forge.

Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5Etymology

The name “Vulcan,” or Vulcanus in the Old Latin, was borrowed directly from the Latin noun vulcanus meaning “fire” and “volcano.” This etymology was likely a reflection of Vulcan’s association with the fires of the forge, but could also reference his mythic upbringing beneath Mt. Etna, an active volcano on the island of Sicily.

Attributes

From metallurgy and smithing to arms and jewelry making, Vulcan was a master of the forge. He was believed to have created the strongest and most sophisticated items of ancient lore, including Jupiter’s lightning bolts and Mercury’s winged helm.

Vulcan’s deformed leg made him something of a pariah amongst the gods. It was this imperfection that compelled Vulcan to seek perfection in his craft.

The Classicist Robert Graves suggested that Vulcan’s deformity related to an ancient practice among North African and Mediterranean peoples, whereby slaves would be trained as smiths and then maimed in order to prevent their escape.[1] According to this interpretation, Vulcan was deformed because—in the popular imagination—blacksmiths were deformed.

Family

Vulcan was the son of Juno and Jupiter, the ruling couple of the Roman pantheon. His full brothers and sisters included Bellona, Mars, and Juventus. Through Jupiter, Vulcan had many half-siblings as well. Among their number were the messenger god Mercury, Proserpina, Ceres’ child famously abducted by Pluto, and Minerva, goddess of wisdom and defender of the Roman state.

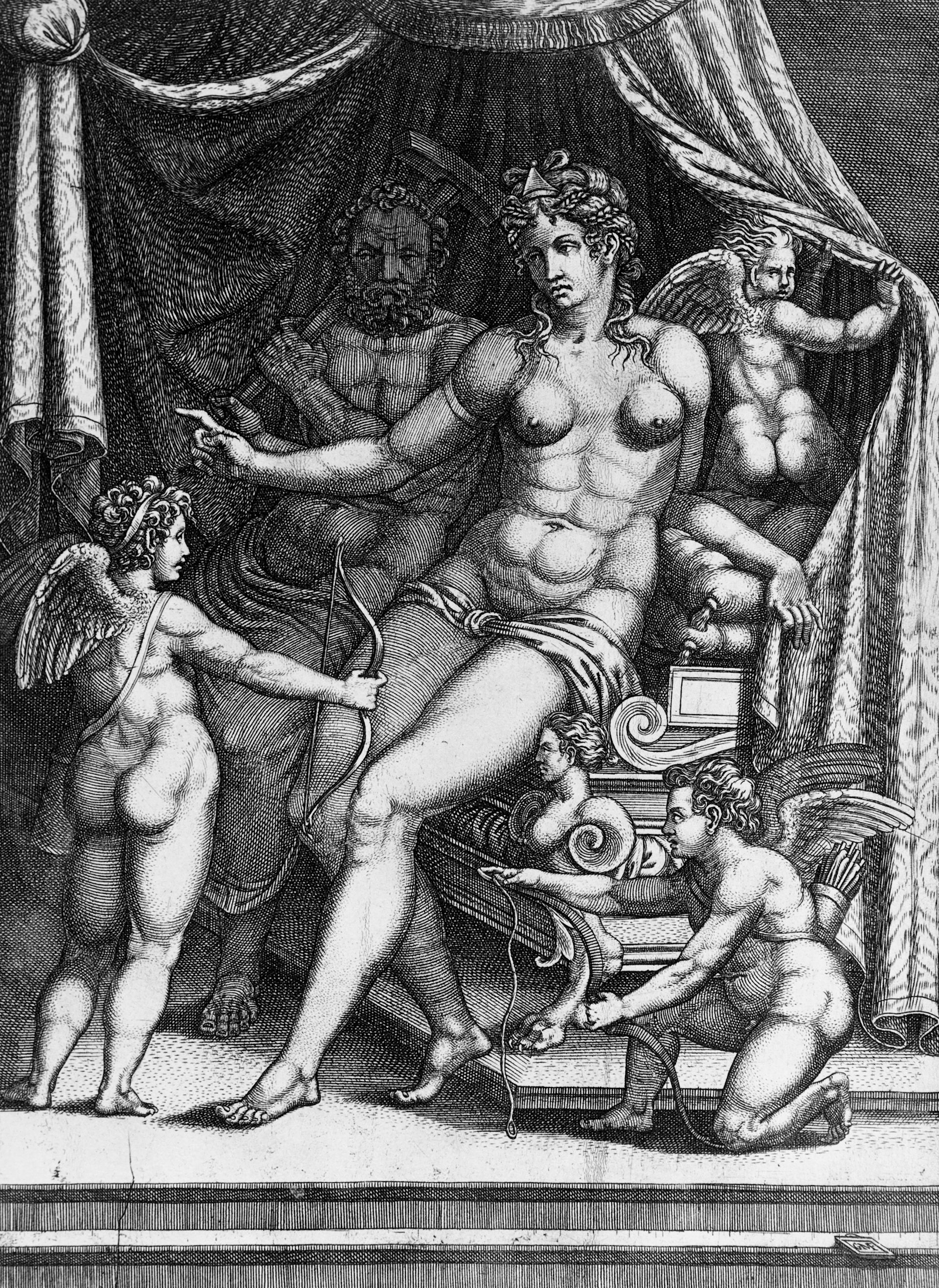

Vulcan married Venus, the goddess of sex, lust, and love, who provided a beautiful contrast to Vulcan’s notorious unattractiveness. Theirs was a loveless and sexless marriage that produced no children.

Venus and Vulcan Seated on a Bed (c. 1550) Italian engraving.

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn the Aeneid the Roman poet Virgil claimed that Vulcan was the father of Caeculus, the founder of Praeneste (modern Palestrina) in Italy. No mother was mentioned.

Family Tree

Parents

Father

Mother

Siblings

Brothers

Sisters

Consorts

Wife

Mythology

Origins

When Juno first looked upon her son Vulcan, she found him to be so ugly that she hurled him from the top of Mt. Etna. The fall injured Vulcan severely, leaving him with the lame leg that would soon become his trademark. In other tellings, Vulcan’s lameness was itself the reason for Juno throwing him from the mountain. His rejection at Juno’s hand left Vulcan with a grudge he would carry the rest of his life.

Raised by nymphs, Vulcan came of age in a cavern beneath the volcanic Mt. Etna on Sicily. As he grew older, he gained the knowledge and skills that would ultimately mold him into a master blacksmith. The caverns provided everything Vulcan needed to learn his trade. He would harvest burning embers from the volcano’s molten core, then heat them in a bellows of his own design. Afterwards, he would heat ores that he had mined from his subterranean surroundings. Vulcan soon discovered that the heated ores yielded excellent crafting materials, such as iron, copper, gold, and silver. Once cooled, these metals could be fashioned into arms, armor, jewelry, and more.

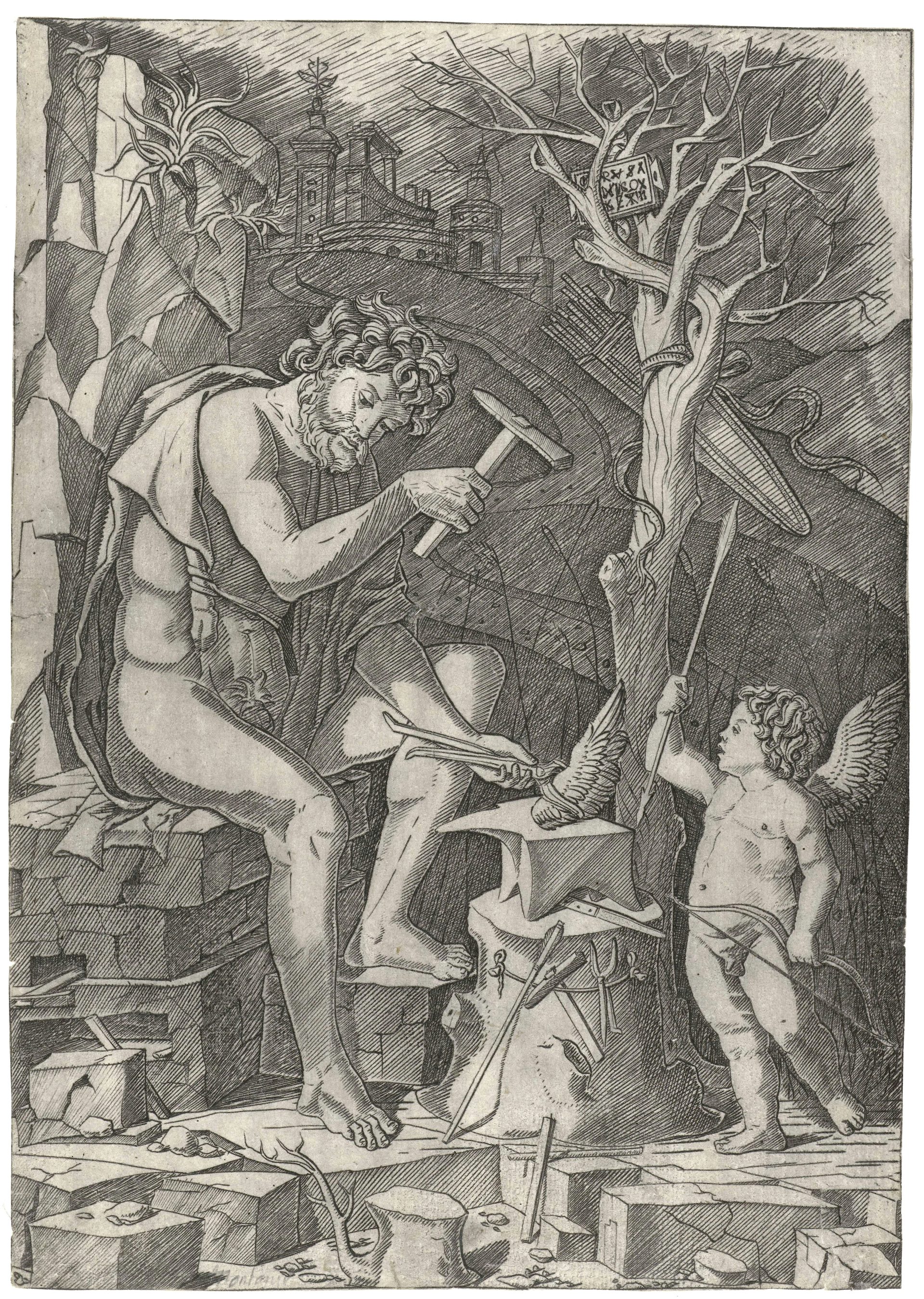

This 15th century Italian engraving depicts a focused Vulcan forging Cupid's wings.

RijksmuseumPublic DomainWorking in his subterranean workshop, Vulcan mastered the art of the forge. Word spread of the master craftsman, and his services eventually became desired by the gods. Vulcan crafted Jupiter’s scepter, aegis, and even his famous lightning bolts. Among other innovations, he also fashioned Mercury’s winged helm and an army of automatons. He also aided in the birth of his half-sister Minerva, whom Vulcan delivered from Jupiter’s forehead using an axe and tongs.

Vulcan, the God with a Mother Complex

In many ways, Vulcan’s rejection at Juno’s hand was the defining moment in his life. After carrying a grudge against her all his life, Vulcan finally decided to claim his revenge. One day, Vulcan crafted a special chair with a hidden mechanism designed to ensnare the person sitting in it. He made it especially for Juno, who sat in the chair and was immediately trapped in place. Vulcan refused to release his mother until he was promised Venus’s hand in marriage.

Eventually, Jupiter intervened. He alone had the power to compel the other gods and goddesses to action, and he ordered Venus to accept Vulcan’s request. He then sent Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy, to fetch Vulcan. After getting Vulcan drunk, Dionysus carried him home to the gods. Once sober, Vulcan released Juno from the chair and accepted the lovely Venus as his wife.

Vulcan and Venus

The marriage of Vulcan and Venus was not a happy one. Repulsed by her husband’s leg and upset by the circumstances of their union, Venus often sought intimacy with others. One of her most notorious relationships was with Mars, a god admired for his primal powers who also happened to be Vulcan’s brother. When Mercury chanced to see the lovers having intercourse in Vulcan’s bed, he immediately told the blacksmith what he had witnessed. Enraged, Vulcan beat the red hot metals of his forge so viciously that sparks flew from the top of Mt. Etna.

Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan (1630) by Diego Velasquez. In this scene, Apollo (far left) informs Vulcan (second from left) that Venus has been cheating on him. Vulcan’s assistants react with shock and surprise.

Museo del Prado, Madrid, SpainPublic DomainVulcan preferred mind over might, however, and bided his time preparing a trap for the lovers, much as he had done for Juno. He crafted a net from material undetectable to the naked eye, then built snares that fit seamlessly inside it. The Roman poet Ovid described the scene in exquisite detail:

Poor Vulcan soon desir’d to hear no more, He drop’d his hammer, and he shook all o’er: Then courage takes, and full of vengeful ire He heaves the bellows, and blows fierce the fire: From liquid brass, tho’ sure, yet subtile snares He forms, and next a wond’rous net prepares, Drawn with such curious art, so nicely sly, Unseen the mashes cheat the searching eye. Not half so thin their webs the spiders weave, Which the most wary, buzzing prey deceive. These chains, obedient to the touch, he spread In secret foldings o’er the conscious bed.[2]

When Venus and Mars next sought the pleasure of the bed, they found themselves quite stuck. As Vulcan burst in laughing, he called for the others gods and goddesses to come and witness the scene:

The conscious bed again was quickly prest By the fond pair, in lawless raptures blest. Mars wonder’d at his Cytherea’s charms, More fast than ever lock’d within her arms. While Vulcan th’ iv’ry doors unbarr’d with care, Then call’d the Gods to view the sportive pair: The Gods throng’d in, and saw in open day, Where Mars, and beauty’s queen, all naked, lay.[3]

Vulcan and the Roman State Religion

The first recorded instance of Vulcan worship can be traced back to the eighth century BCE, when a shrine was built for him by the Romans. In the third century BCE, the Romans would build a temple for Vulcan on the Campus Martius. The temple did not last long, however, as it was struck by lightning and subsequently destroyed.

The chief festival held in Vulcan’s honor was the Vulcanalia. Held each year on August 23, the Vulcanalia centered on the god’s association with fire. Celebrants lit candles and started bonfires into which they would throw living fish and small animals. These sacrifices were thought to propitiate the god and ward off wildfires during the arid season.

Pop Culture

In Star Trek, the name Vulcan was given to a race of extraterrestrial humanoids (of whom Spock was the best known). Like the god Vulcan, the Vulcans believed in mind over matter. The aliens would often mute their emotional reactions, and always used logic as their guiding principle.

A statue of Vulcan stands tall in Birmingham, Alabama, celebrating the city's metallurgical history. Completed in 1904, it is the largest cast iron statue in the world.

Carol M. Highsmith, Library of CongressPublic DomainVulcan’s influence has also survived in the word “volcano.” The term is used to describe vents in the earth’s crust that allow lava and hot gases to escape.