Liber (Bacchus)

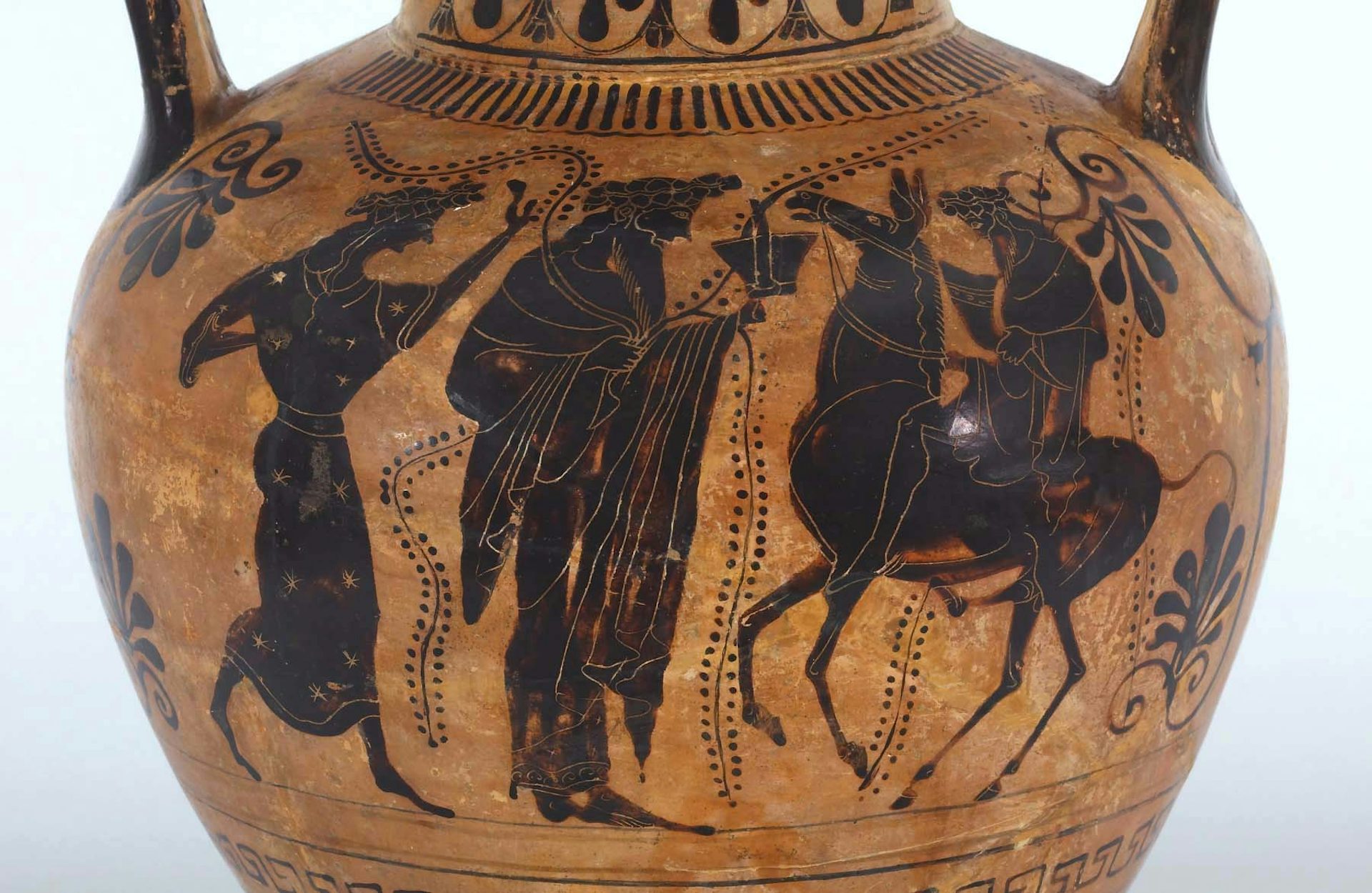

Attic black-figure neck amphora by the Circle of the Antimenes Painter (ca. 520 BCE) showing Dionysus (center) accompanying Hephaestus riding a donkey (right) as a maenad looks on (left)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0Overview

Liber (also known as Liber Pater or Bacchus) was the Roman god of fertility and wine, identified from an early period with the Greek god Dionysus. He was worshipped alongside Ceres and Libera on the Aventine Hill in Rome.

Liber, like the Greek Dionysus, represented the more unrestrained aspects of life. He was honored annually at the Liberalia, a fertility festival celebrated in March.

Key Facts

Who was Liber’s Greek equivalent?

Liber (or Liber Pater) was commonly identified with the Greek god Dionysus; both were gods of fertility and wine. Roman literature often referred to Liber as Bacchus, an important cult title of Dionysus.

Though Liber seems to have originated as a native Italian god, the Romans increasingly merged his mythology and iconography with that of the Greek Dionysus. In cult, Liber was thought to have been based on Iacchus, one of the gods of the Eleusinian Mysteries in Greece.

The lame Hephaestus appears on a donkey with Dionysus as the central figure of this Greek pottery created c. 520 BCE. This famous and comedic scene was depicted often on pottery made in Attica and Corinth.

The Walters Art MuseumCC0What does Liber’s name mean?

The name Liber is likely derived from the Latin verb liberare, meaning “to set free” (as an adjective, liber means “free”). But other etymologies are also possible, with some scholars suggesting that the name is related to the Greek word for “libation.”

Without Ceres and Liber, Venus would Freeze by Hendrik Goltzius (ca. 1600–1603)

Philadelphia Museum of ArtPublic DomainHow was Liber worshipped?

In Rome, the cult of Liber was centered on the Temple of Ceres, located on the Aventine Hill. Liber was one of the members of the “Aventine Triad,” along with the agriculture goddess Ceres and the more obscure goddess Libera.

Like Ceres and Libera, Liber was closely associated with the plebeian population of Rome. His main festival was the Liberalia, a fertility festival in which a large phallus was paraded through the streets of Rome.

Italian bronze medal of Ceres (late 15th–early 16th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainLiber’s Double Birth

The Romans seem to have originally regarded Liber as the son of Ceres. However, they eventually adopted the Greek myth of the double birth of Dionysus (Liber’s Greek equivalent), making Liber’s parents Semele and Jupiter (Zeus).

In this myth, Jupiter’s wife Juno (Hera) became jealous of her husband’s affair with the mortal Semele. She therefore tricked Semele into making Jupiter come to her in his true divine form— knowing full well that, as a mortal, Semele would be unable to endure the experience.

When Semele died, Jupiter took the growing infant from her womb and sewed him into his thigh. Later, when the time was right, the god Liber was born from his father’s thigh.

Jupiter and Semele by Sebastiano Ricci (ca. 1695)

Uffizi Gallery, FlorencePublic DomainRoles and Powers

Liber was an Italian nature god who supervised fertility, vegetation, and wine.

Much like the Greek Dionysus or Bacchus (with whom he was commonly identified), Liber came to be seen first and foremost as the god of wine and viticulture.[1] But he had several secondary functions as well. For example, he was sometimes invoked as a source of inspiration for poets[2] or as a protector of lovers.[3]

Attributes

Liber, like Dionysus or Bacchus, was usually imagined as a young man wearing a crown and carrying a thyrsus (a stem of narthex or fennel topped by a pinecone).[4] The thyrsus was one of Dionysus’ most distinctive attributes and was therefore adopted by the Romans for their Liber. Vines and grapes were also important attributes of Liber.[5]

Fourth-style wall painting from Pompeii showing Bacchus (Dionysus; center) with Venus (Aphrodite; right), Sol (Helios; left) and other gods (first century CE), from the House of M. Gavius Rufus in Pompeii

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0Later, as Liber was increasingly identified with the Egyptian god Osiris, he was sometimes described as horned.[6]

Liber was accompanied wherever he went by an entourage of revelers and beasts, who were said to engage in orgies at night.[7] This entourage included frenzied worshippers known as maenads, as well as satyrs and pans—creatures that were half-human and half-animal. In Roman literature, Liber was also sometimes associated with the half-human, half-goat fauns.

Liber’s attributes were occasionally adopted by historical figures who wanted to associate themselves with the god. The Roman politicians Marius,[8] Pompey,[9] and M. Antonius,[10] for example, sometimes represented themselves with the attributes of Liber, as did the Roman emperor Elagabalus.[11]

Iconography

In Roman art, Liber was more or less identical with the Greek god Dionysus or Bacchus. Like Dionysus, Liber was shown as a beardless and even effeminate young man, easily recognized by the thyrsus, grapes, and ivy garlands that he carried.

No religious cult images of Liber have survived, but the god often appeared in Roman depictions of scenes drawn from Greek mythology. In particular, representations of the “triumph” of Liber, showing processions of the god at the head of a band of revelers, became popular on Roman sarcophagi.[12]

Marble sarcophagus from Proconnesus showing the triumph of Bacchus (ca. 215–225 CE)

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainEtymology

The name Liber is usually thought to be connected with the Latin verb liberare, meaning “to free” or “to liberate.” The ancients traced this etymology to the fact that those who partook in Liber’s gift of wine spoke and behaved in a free and unrestrained manner.[13] The god was often addressed as Liber Pater, “Father Liber.”

Liber’s name may also be related to the ancient Greek verb λείβειν (leíbein), meaning “to offer libation,” as wine was commonly used in the Greek and Roman ritual of libation.[14]

Alternatively, Liber’s name can be interpreted in relation to the goddess Ceres, the chief goddess of the “Aventine Triad” to which Liber belonged. In the Aventine cult, Ceres was regarded as the mother of Liber and Libera, the junior gods of the triad; the names of these two gods could thus be understood as a reference to their role as the “children”—Latin liberi—of Ceres.[15]

Pronunciation

English

Latin

Liber Liber Phonetic

IPA

[LAHY-ber] /ˈlaɪ bər/

Other Names

The most important alternative name for Liber was Bacchus (Greek Βάκχος, translit. Bákchos), a popular cult title of the Greek god Dionysus. Liber was commonly identified with Dionysus (just as the other chief gods of the Roman pantheon were identified with important Greek gods). In Roman poetry especially, which was heavily inspired by Greek models and myths, Liber was frequently referred to as Bacchus.

Bacchus by Caravaggio (ca. 1598)

Uffizi Gallery, FlorencePublic DomainFamily

In his original Italian mythology, Liber was regarded as a child of Ceres, the goddess of agriculture. His consort was the goddess Libera (who was also his sister). Together, Ceres and her children were worshipped as a triad in their temple on the Aventine Hill in Rome.[16]

By the end of the first century BCE, however, the Romans had transferred the common Greek myth about the birth of Dionysus to their Liber. According to this account, Liber was the son of Jupiter (Zeus) and Semele, a princess from the city of Thebes in central Greece.[17]

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

Liber was an Italic-Roman god of obscure origins. One early theory posited that he was another form of Jupiter—the “Jupiter Liber” attested in some records—but this is now largely regarded as an incorrect interpretation. Most scholars today consider Liber to be an ancient vegetation god.

The earliest archaeological evidence for Liber comes from a few cistae (a type of vessel) from Praeneste in Latium; these were inscribed with his name in the fourth century BCE.[18] Liber is also named on a third- or second-century BCE cippus (boundary stone) from Pisaurium.[19]

According to the ancient Romans (as well as the ancient Greeks), Liber was introduced to Rome from Greece in the early fifth century BCE. The story goes that in 496 BCE, during the Romans’ conflict with the Latin League, the Sibylline Books instructed the Romans to import the divine triad of Demeter, Kore, and Iacchus from the Greek city of Eleusis.

Fragment of the "Great Eleusinian Relief" showing Demeter (left) and Persephone (right) with the young Triptolemus (center), Roman copy (ca. 27 BCE–14 CE) after a Greek original (ca. 450–425 BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, AthensPublic DomainThe Romans did as the Sibylline Books instructed, translating Demeter into Ceres, Kore into Libera, and Iacchus—understood as another name for Dionysus—into Liber. This triad was honored with a new temple on the Aventine Hill in Rome.[20]

The Birth of Liber

The Romans seem to have originally regarded Liber as a child of the agriculture goddess Ceres. Eventually, though, a different version of his birth became more popular, based on the myth of the double birth of Dionysus (the Greek god commonly identified with Liber).

According to this myth, Liber was the son of Jupiter (Zeus), the ruler of the gods, and Semele, a mortal princess from the Greek city of Thebes. Jupiter’s affair with Semele stoked the jealousy of his wife Juno (Hera), who plotted to destroy her mortal rival.

A handful of Roman authors, adapting the Greek myth, told of how Juno came to Semele in the form of her nurse Beroe. The goddess encouraged Semele to make her lover prove that he was really Jupiter by visiting her in his divine form—knowing very well that no mortal could endure the sight of Jupiter in his full glory.

Semele took Juno’s treacherous advice and made Jupiter swear an unbreakable oath to grant her any request. Once she had revealed what she wanted, Jupiter had no choice but to comply: he showed himself to Semele as thunder and lightning. The unfortunate woman was unable to bear the sight:

The mortal dame, too feeble to engage

The lightning’s flashes, and the thunder's rage,

Consum'd amidst the glories she desir’d,

And in the terrible embrace expir’d.[21]

When Semele died, Jupiter took the unborn child from her womb and sewed him into his thigh; once Liber had come to term, he was “born” from his father. Afterwards, Jupiter gave the child to the nymphs of Nysa so that they could bring him up.[22]

The Death of Semele by Peter Paul Rubens (before 1640)

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, BrusselsPublic DomainOther Myths

There is no evidence of any original mythology for the god Liber; instead, the Romans adopted the mythology of the Greek god Dionysus, often even referring to Liber by the Greek name Bacchus (a cult title of Dionysus). The result is that many Greek myths about Dionysus are transmitted via Roman sources for Liber.

One early Greek myth, repurposed by the Roman poet Ovid, told of how Liber was abducted by sailors. Struck by the beauty of the youthful Liber, the treacherous sailors decided to fetch a high price for him by selling him into slavery. But Liber easily escaped his captors, taking over their ship and turning them into dolphins:

Around their oars a twining ivy cleaves,

And climbs the mast, and hides the cords in leaves:

The sails are cover’d with a chearful green,

And berries in the fruitful canvass seen.

[...]

The God we now behold with open’d eyes;

A herd of spotted panthers round him lyes

In glaring forms; the grapy clusters spread

On his fair brows, and dangle on his head.

And whilst he frowns, and brandishes his spear,

My mates surpriz’d with madness or with fear,

Leap’d over board; first perjur’d Madon found

Rough scales and fins his stiff’ning sides surround…[23]

The Dionysus Cup by Exekias (ca. 530 BCE), showing Dionysus sailing in a ship with dolphins

MatthiasKabelCC BY-SA 3.0Other myths described how Liber dealt with those who failed to acknowledge his divinity. For example, when Lycurgus, a Thracian king, attacked Liber’s followers, the god punished him with madness and death.[24] When the Theban king Pentheus tried to suppress the worship of Liber in his city, the god caused the women of Thebes—led by Pentheus’ mother Agave—to tear apart the blasphemer in a divine frenzy.[25] And when the Minyades, daughters of the Boeotian king Minyas, neglected Liber’s rites, he turned them all into bats.[26]

Liber, like his Greek counterpart Dionysus, was a well-traveled god. Roman authors often alluded to his conquest of India, which became a popular parallel to Roman imperialism.[27] Some authors even claimed that Liber traveled as far west as the Iberian Peninsula.[28]

Another popular myth told of Liber’s seduction of the Cretan princess Ariadne. A figure of Greek mythology, Ariadne helped the Athenian hero Theseus kill the Minotaur when he was sent to Crete as a prisoner. Theseus took Ariadne with him when he fled Crete, only to faithlessly abandon her on the island of Naxos (or Dia).

It was there that Liber (or Dionysus, in Greek texts) found the princess and fell in love with her. He made her his bride, gifting her a beautiful golden crown that would become the constellation Corona Borealis.[29]

Bacchus and Ariadne (17th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOther Roman tales of Liber, also largely derived from Greek mythology, detailed his descent to the Underworld to bring back his mother Semele;[30] his battle with the Giant Rhoetus during the war between the gods and the Giants;[31] and even the Orphic myth of Dionysus Zagreus, in which the young god was torn apart and devoured by the Titans.[32]

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

The Romans themselves believed that Liber was a Greek god. His cult was based on the Eleusinian cult of the Greek Iacchus (Iacchus, in this case, was understood as another name for Dionysus or Bacchus, the Greek god of wine and intoxication).

The chief sanctuary of Liber was the Temple of Ceres on the Aventine Hill, erected in the early fifth century BCE at the behest of the Sibylline Books. This temple belonged to the triad of Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, and her subordinates Liber and Libera (the Romans regarded these three gods as the equivalents of the Greek Demeter, Iacchus, and Kore, respectively).

The Aventine temple became a center for plebeian religious cult in Rome. As a result, Liber—like Ceres and Libera—was closely associated with the plebeians.

Votive altars with inscribed dedications to Liber

Museo Monográfico de Conimbriga / ElisadojmCC BY-SA 3.0There is some evidence (from the remains of the Fasti Farnesiani) that one other sanctuary of Liber was erected in Rome. This sanctuary seems to have stood on the Capitoline Hill, but nothing definitive is known about it.

As Roman power expanded, temples of Liber were erected in other parts of the empire. One notable example is the astonishingly well-preserved Temple of Bacchus in modern Baalbek (in Lebanon), commissioned by the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius in the second century CE.

A partially reconstructed Temple of Bacchus at the Baalbek temple complex in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. Commissioned during the reign of Antoninus Pius in the mid-second century CE, the Temple of Bacchus was a testament to the far-reaching influence of Roman religion.

Vadim Nefedov / iStockFestivals and Rituals

The most important festival of Liber was the Liberalia, celebrated annually on March 17. This festival featured wreathed old women who sold honey cakes (called liba) to passersby;[33] a phallus transported on a wagon through the city as celebrants sang crude rustic songs;[34] and masks of the god hung on trees.[35]

On the day of the Liberalia, seventeen-year-old Roman boys would ceremonially pass from childhood to adulthood, exchanging the toga praetexta for the toga virilis.[36]

Liber was honored at other festivals as well. For instance, he was one of the gods celebrated at the Ludi Ceriales, connected with the Aventine temple that he shared with Ceres and Libera. Sacrifices to Liber were also made at various wine and harvest festivals.

The notorious Bacchanalia were also connected with Liber in a sense, though these were more properly the rites of the Greek Dionysus rather than the Italian Liber. Concrete details about the Bacchanalia are scarce, partly due to a lack of sources, and partly due to the distortions of ancient authors like Livy who condemned the Bacchic cults. At the very least, we know the festivities included drinking, carousing, and reveling.

The Bacchanalia were violently suppressed in Rome in 186 BCE, but they continued to be celebrated in other cities throughout Italy, and even in the Near East.[37]

Bacchus, Ceres, and Amor by Hans von Aachen (between 1595 and 1605)

Kunsthistorisches Museum, ViennaPublic Domain