Osiris

Overview

Osiris, the “Mighty One,” was both god of the dead and a central figure of Egyptian mythology. His cult arose around 2600BCE, as those of competing deities, including Andjety of Busiris and Khentamentiu of Abydos, declined.[1] For nearly 3,000 years, Osiris would stand as one of the most prominent Egyptian gods.

The tradition of mummification mirrored Osiris’s own experiences. As the god of the afterlife, he decided who was worthy of reincarnation, and who was not.

This statuette of Osiris (c. 588–526 BC) features the deity's characteristic atef (headdress) and shroud.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainEtymology

Almost all names from Egyptian mythology have made their way to English through the Coptic language, which was first translated into Greek before being translated into Latin.

This etymological chain has made the original meaning of these ancient names difficult to decipher. Before the development of the Coptic language (the most recent form of Ancient Egyptian) between 300BCE and 200CE, the Egyptian written language did not include any vowels.[2] While the presence of vowels was indicated by certain characters, the nature of the vowels themselves was left ambiguous.

The best approximation of Osiris’s name as it was written in Ancient Egyptian is the unpronounceable letter jumble: jsjrt.[3]

While the meaning of Osiris’s name is unclear, the epithet “Mighty One” is commonly attributed to him and may allude to his role as Death personified.[4]

One of Osiris’s epithets, “Foremost of the Westerners,” originated from Khentamentiu of Abydos, a funerary deity that Osiris ultimately replaced.[5]

Attributes

Osiris was usually portrayed as a mostly-mummified king. He was often depicted wearing an atef—a combination of the hedjet crown, two ostrich feathers, and two horns. Atefs were synonymous with Osiris, though he was not the only god to wear one.[6]

The little skin left unwrapped—usually his face and hands—was typically green or black. These colors may originally have been connected with decay, but as time went on they were said to reflect Osiris’s role in the cyclical nature of life and death, as manifested by plants.[7]

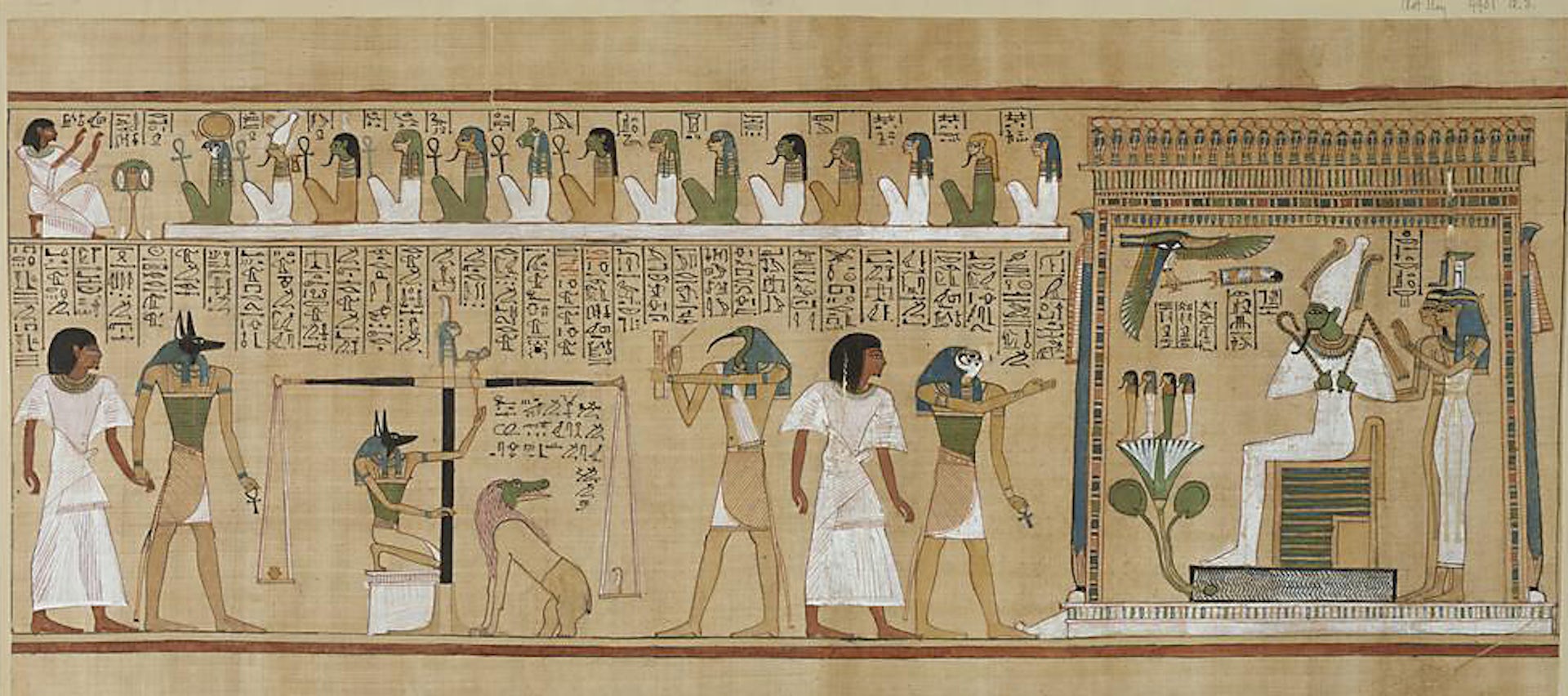

A partially mummified (and green-skinned) Osiris presides over the rituals of the afterlife. Bearing his atef crown, as well as his customary crook and flail, this depiction of Osiris features all of his traditional elements. The Book of the Dead of Hunefer (Hw-nfr), Sheet 3.

The Trustees of the British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0Osiris was often seen carrying a crook and flail. The crook, a symbol of Egyptian kings, was derived from the tools used by shepherds tending to their sheep. The flail, meanwhile, has been interpreted as a whip or goad indicative of the king’s martial power; others believe that it represented a threshing tool indicative of agricultural success.

Osiris ruled on earth before becoming lord of the underworld, though he was still considered a god in all stages of his mythos. At 8 cubits, 6 palms, and 3 fingers tall (15’3” / 4.7 meters) he would certainly have been an intimidating presence.[8]

Family

Osiris was the first child of the sky goddess Nut and the earth god Geb. His siblings included Horus the Elder[9], Set, Isis, Nephthys.

Osiris had several notable children. He famously fathered Horus the Younger with his sister/wife Isis following his resurrection, and unwittingly sired Anubis with Nephthys.

His other children include Babi, a mythical man-eating baboon, and Sopdet, the personification of the star Sirius.[10]

Family Tree

Mythology

The stories of Osiris were some of the best-preserved tales in the Egyptian mythos. Most knowledge of Osiris’s mythos originally came from Greek accounts, such as those of Plutarch, Diodorus Siculus, Firmicus Maternus, and Macrobius. These accounts have since been confirmed by fragments of the ancient Egyptian record.

Origin Myth

When Osiris was born, he came into the world wearing his distinctive atef crown. The crown was a symbol of Ra’s decision to have Osiris succeed his father as king.

On the day of Osiris’s birth, a man named Pamyles heard a voice while drawing water at the temple of Thebes. The voice told Pamyles to spread the word that the great king Osiris had been born. Pamyles did so, and was rewarded with the honor of educating the god-king Osiris.[11]

While some sources have suggested that Osiris’s prophesied rule was a source of strife between him and his father Geb, other sources have omitted any mention of such contention.[12]

The Earthly Reign of Osiris

By all accounts, Osiris was a benevolent and effective king. The Egypt of Osiris’s time was barbarous, and cannibalism was widely practiced. Osiris put a stop to such practices and introduced the Egyptians to wheat, barley, grapes, wine, and copper tools.[13]

After civilizing Egypt, Osiris embarked on an expedition to introduce the world to wheat, barely and agriculture. Before leaving, he appointed his sister/wife Isis to rule in his absence.

After assembling an army of courtiers, satyrs, and agricultural experts, Osiris initially traveled south toward Ethiopia.[14] He eventually traveled as far as India in spreading his benevolent rule. Osiris was not always kindly, however. He destroyed those who resisted his program of enlightenment, a barbarian king in Thrace among them.[15]

The Murder of Osiris

While Osiris was gone, Isis ruled Egypt without any major problems. Not everyone was content with the positive state of affairs, however. Osiris’s younger brother Set was jealous of his brother’s achievements, and sought to assassinate him.[16]

Set gathered 72 conspirators—including the queen of Ethiopia—and began to plot his brother’s demise. Working in secret, Set took precise measurements of Osiris’s body and devised an incredibly ornate box to match them. Set presented the box at a party, telling partygoers that whomever fit in the box could keep it. Each guest tried the box in turn, only to find it did not quite fit. Finally, Osiris laid down in it and found he fit perfectly.[17]

As soon as the king had laid down, Set and his conspirators nailed the lid shut and sealed the box with molten lead. As Osiris suffocated to death, the conspirators tossed the chest into the Nile and watched it float out to sea.[18]

Isis’s Search for Osiris

Isis was in the village of Chemmis (or Koptos), near Thebes, when she felt her husband’s death. Sensing the truth in her feelings, she immediately went into mourning.[19]

A wooden statue of Isis in mourning (332–30 BCE).

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIsis set out in search of her husband’s body, but went many months without success. Eventually, however, she came across some some children who told her they had seen a chest floating down the Nile.

Upon further investigation, Isis discovered that the chest had washed ashore in Byblos and quickly began to search the area.[20]

When Osiris washed ashore at Byblos, a great tree grew around his chest. King Malkander and Queen Athenais had heard tales of this magnificent tree, and decided to use it as a pillar in their palace. They cut the tree down and unwittingly took a section containing Osiris back to the palace.[21]

When Isis arrived in Byblos, she realized that Osiris was not there and sat in melancholic silence. Coincidentally, Queen Athenais’ handmaids were bathing at Byblos when they found themselves taken in by Isis’s silent beauty. As they began to converse with the goddess, they became perfumed by their proximity to her. When the handmaids returned to the palace, the queen asked them about their lovely fragrance. The handmaids then told her of their meeting with Isis.

Intrigued by the handmaids’ tale, the queen visited the shore and, after meeting with Isis, asked her to serve as her child’s nurse. Isis not only accepted Athenais’ offer, but also stated that she could cure her son’s incurable illness—on the condition she be able to work in secrecy.

Depending on the version of the tale, the queen either intentionally set out to discover Isis’s methods, or accidentally stumbled upon the process. The end result was the same—Isis revealed herself as a goddess. Upon revealing herself, Isis either demanded access to Osiris’s entombed body, or was offered anything she wanted as a gift.[22] Once Isis received Osiris’s body, the wave of grief she experienced was so powerful that it killed one of the monarchs’ children.

Isis returned home with Osiris’s body, and was able to revive him long enough to impregnate herself with the god Horus.[23] Isis, Nephthys, Anubis, and Thoth then embalmed and mummified Osiris’s body before hiding it away.

Even in death, Osiris would find no peace. Set discovered his body while on a moonlit boar hunt and tore it into 14 pieces. While some stories say he scattered Osiris’s body parts about Egypt himself, most sources suggest that he simply threw the pieces back into the Nile.[24]

Isis once again set out to find her wayward husband and managed to collect 13 of the pieces. The 14th—Osiris’s phallus—was eaten by an alligator (or fish) and was lost forever.

In order to prevent Set from repeating his last misadventures, Isis made a waxen copy of each body part and buried them separately. Local priests were charged with protecting each body part, with each being told that their location was the true burial site of Osiris.[25]

Ultimately, Osiris’s body (including a wax replacement phallus) was reassembled. While Isis’s magic had been sufficient to revive Osiris long enough to conceive Horus, he would never again reside in the land of the living. Osiris instead arrived in Duat, the Egyptian underworld. There he served as lord of the dead, judging those who sought to follow him into the afterlife.[26]

The Tales of Osiris According to Egyptian Sources

The most popular accounts of Osiris’s tale were written by the Greek scholars Plutarch and Diodorus. Plutarch lived from 46-120CE, while Diodorus lived in the first century BCE, roughly 2,500 years after the cult of Osiris rose to prominence. As such, their tales (while not entirely fabricated) did not necessarily reflect the Osiris worshipped throughout most of Egyptian history.

The accounts of Osiris’s murder found in Egyptian sources were much more brief, and came to us via the Pyramid Texts and the Papyrus Salt 825.

Pyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts, which date back to the late Old Kingdom and the First Intermediate Period (2660-2066BCE), took their name their place of origin.[27] These texts contained fragmentary mentions of the murder of Osiris, as well as Isis and Nephthys’s subsequent search for his body.

The texts made it clear that Osiris either drowned or was thrown into water after his death, offering partial confirmation of later versions of the story.[28]

Papyrus Salt 825

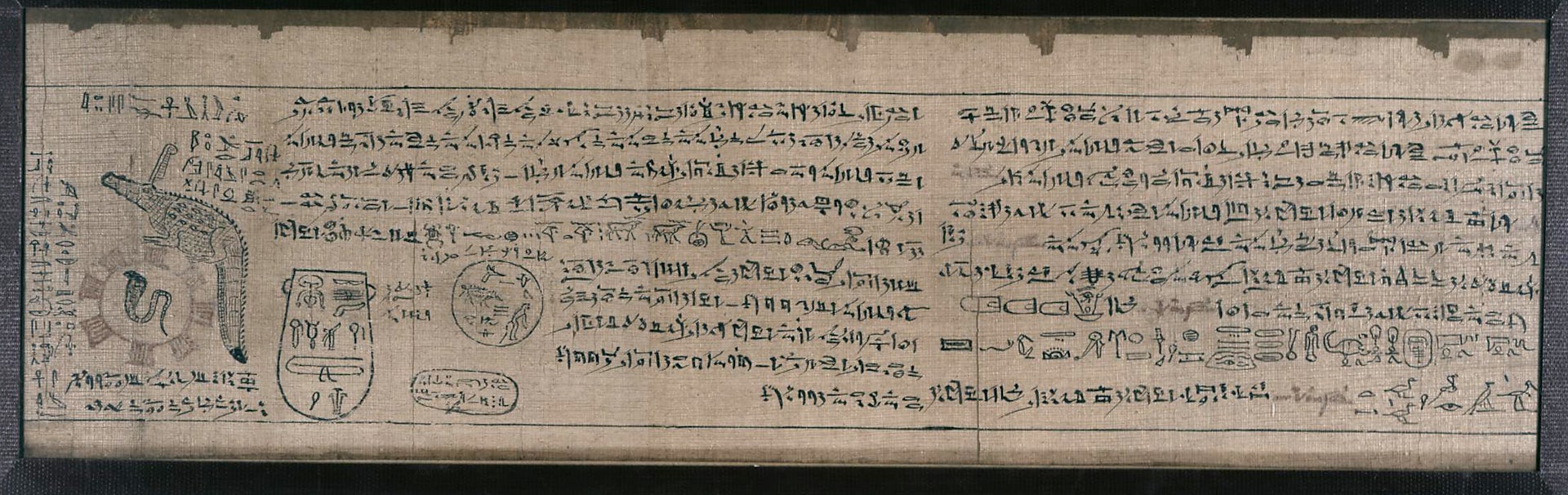

The Papyrus Salt 825—so called because the series of papyri were purchased from Henry Salt—dated back to the Ptolemaic Period (332-30BCE). The papyrus contained an incantation entitled “The End of the Work” which was meant to be delivered at the conclusion of the mummification process.[29]

The Papyrus Salt 825.

The Trustees of the British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0In Egyptian religious tradition, such spells were thought to be the same as those in the myths told about their gods and goddesses. “The End of the Work” would have been the spell delivered over the mummified body of Osiris before he traveled to Duat. By extension, the spell would enable other recently mummified souls to enter Duat as well.[30]

Osiris as Judge of the Afterlife

The Egyptians believed that people were unified beings made from both spiritual and corporeal components. This union dissolved at the time of death, with the ka (body) remaining behind and the ba (soul) flying on to the afterlife in the Duat.

After traversing through the Duat to reach Osiris, the deceased would have their sins weighed against the feather of maat.[31]

Those who were righteous in life—or had spells inscribed on the heart scarab they were mummified with—were then free to exit the Hall of Judgement, and their spiritual ba would be reunited with their corporeal ka.

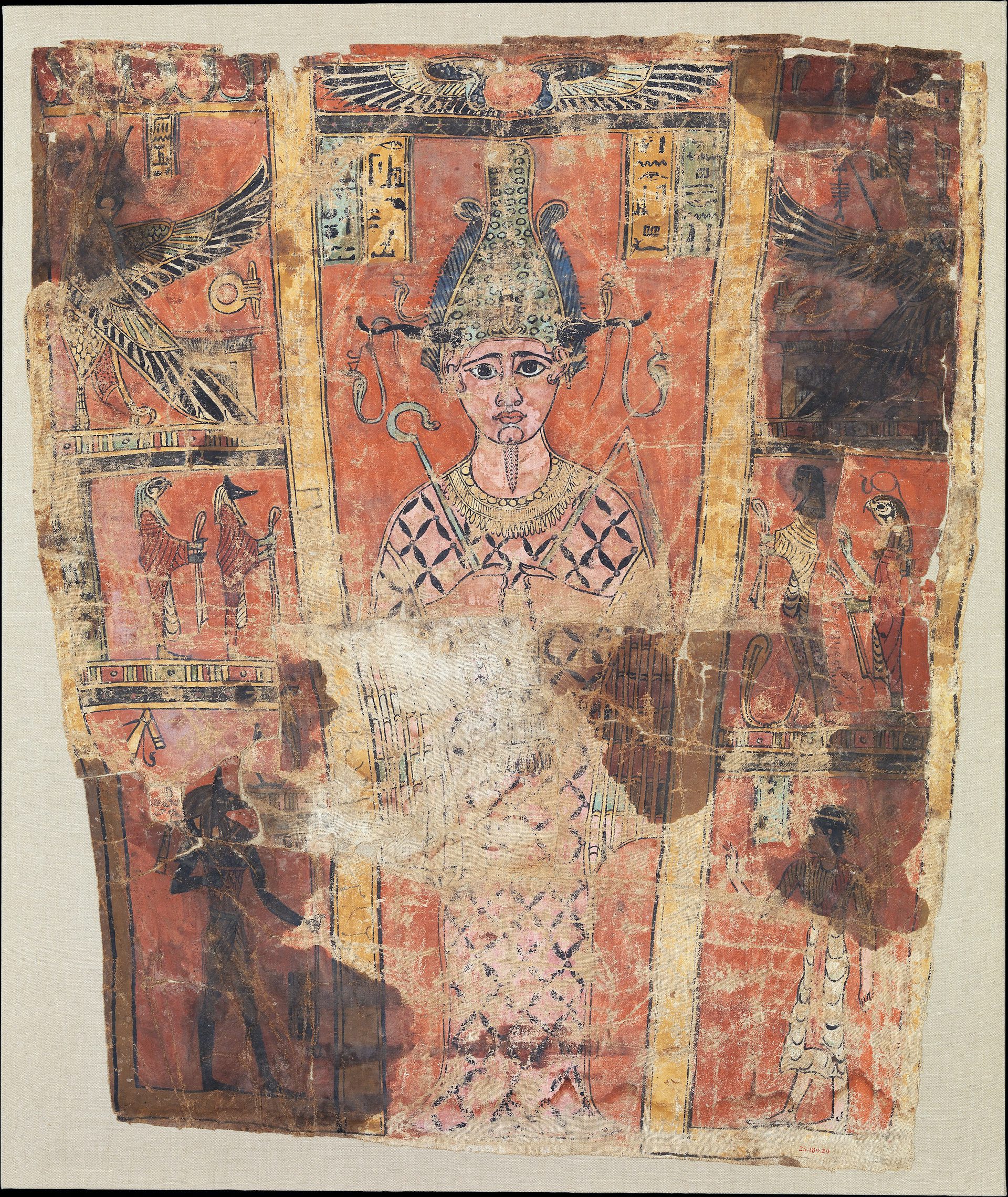

Osiris adorns this burial garment from around 125 CE—a time when Egypt was under Roman rule.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThose who failed to pass the test would then die a true death and be removed from existence by the Ammit—a beast with the head of a crocodile, the body of a lion, and the haunches of a hippopotamus. The most unfortunate of souls would be tortured by Osiris’s demonic associates prior to their obliteration.[32]

Pop Culture

Osiris was a playable character in the 2015 multiplayer-online battle-arena (MOBA) video game Smite.

Since the mid-1990s, Osiris has been rising steadily in popularity as a given name. While the name is still relatively uncommon, babies are seven times more likely to be named Osiris now then they were in 1995.[33]

In The Animatrix segment “Final Flight of the Osiris,” Osiris was the name of the ship that discovered a machine army digging their way to Zion.