Ariadne

Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian (1520–1523)

National Gallery, LondonPublic DomainOverview

Ariadne, daughter of the Cretan king Minos and his wife Pasiphae, is best remembered for helping the hero Theseus slay the Minotaur. She became so enamored with Theseus when he arrived in Crete that she decided to assist him on his mission (betraying her father in the process). She later fled her home to accompany Theseus to Athens.

Whether by design or by accident, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos during his homeward voyage. Ariadne despaired until she was found by the god Dionysus, who married her and gave her many precious gifts. These included a golden crown that was later placed in the heavens as the constellation Corona Borealis.

Key Facts Was Ariadne a goddess?

Many scholars have argued that Ariadne was originally a Minoan nature goddess. Later, she was worshipped in connection with marriage and death in Naxos, Cyprus, and a handful of other sites.

In the common version of her myth, however, Ariadne was not a goddess but rather a mortal princess from Crete. While some sources claimed that she was made immortal after marrying the god Dionysus, most maintained that she simply died of old age, like other mortals.

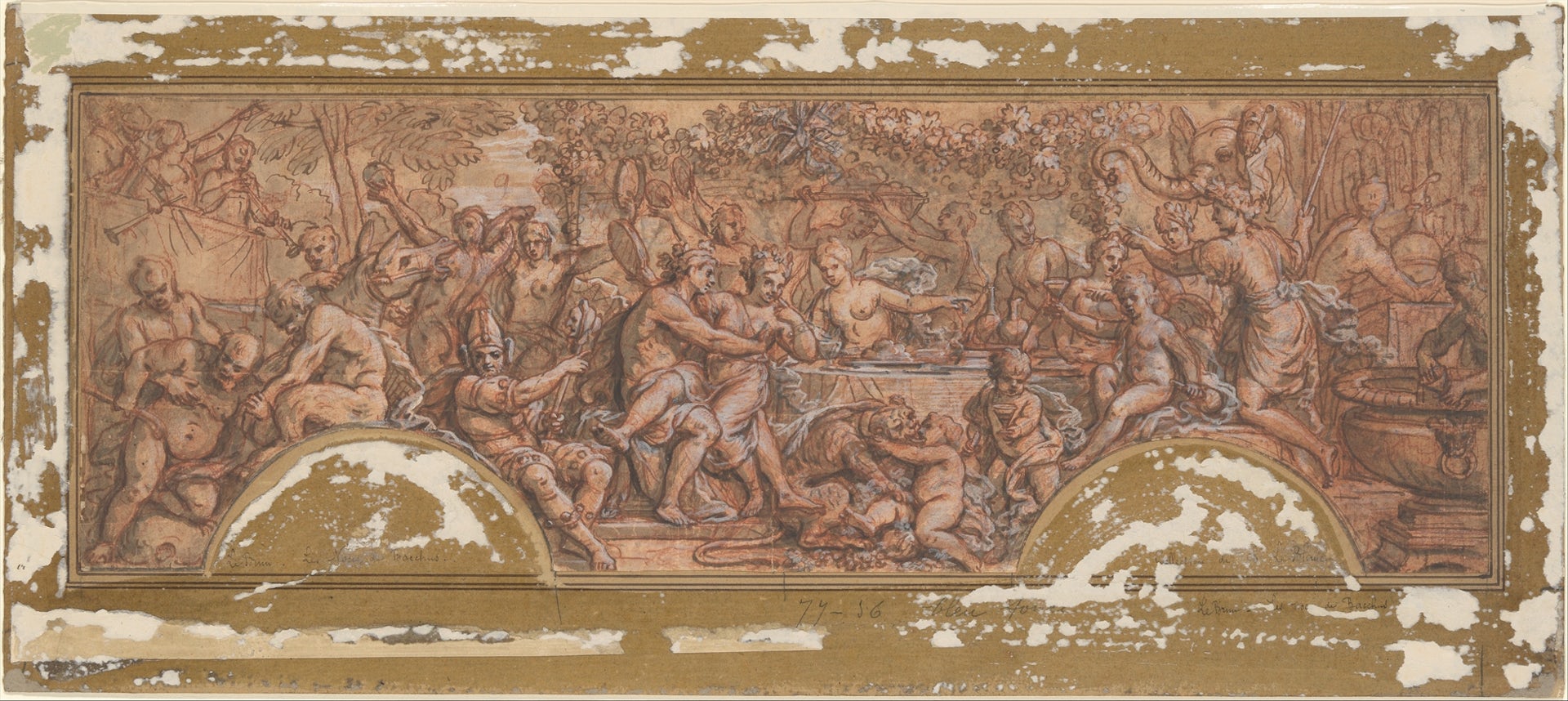

Bacchus and Ariadne by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1720s)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWhy did Theseus abandon Ariadne?

There are different explanations for why Theseus abandoned Ariadne on Naxos. According to some sources, the fickle Theseus tired of Ariadne or fell in love with another woman. According to others, he forgot her by mistake. And according to others still, Theseus was commanded by the gods to leave Ariadne behind so she could marry Dionysus instead.

Attic black-figure neck-amphora attributed to the Edinburgh Painter (ca. 500 BCE) showing Theseus fighting the Minotaur as a female figure (Ariadne?) stands by

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAccording to one famous myth, Dionysus found Ariadne on Naxos shortly after she was abandoned by Theseus and decided to marry her. Ariadne was the most important of Dionysus’ mythical consorts, and in some traditions she was even granted immortality so that she could live beside her divine husband forever.

Ariadne bore Dionysus several sons, including Staphylus, Oenopion, and Thoas. Some said that Dionysus gave Ariadne a golden crown as a gift, which was later turned into a constellation in her honor.

Bacchus and Ariadne by Guido Reni (between 1619 and 1620)

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtPublic DomainAriadne Helps Theseus Defeat the Minotaur

The hero Theseus was sent to Crete as an offering for the Minotaur. But Ariadne fell in love with him at first sight and resolved to help him defeat the monster.

Before Theseus entered the Labyrinth—the Minotaur’s maze-like lair—Ariadne gave him a ball of thread. She instructed him to unravel the thread as he went through the Labyrinth, kill the Minotaur, then follow the thread back to the entrance.

After Theseus had slain the Minotaur and escaped the Labyrinth, he set sail with Ariadne for his home of Athens. But on the way, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos, where she later married the god Dionysus.

Metope relief from the Treasury of the Athenians at Delphi (ca. 500 BCE) showing Theseus fighting the Minotaur

Archaeological Museum of Delphi / ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0Attributes

Ariadne was a beautiful princess from Crete. Her main attributes were the ball of thread she gave to Theuseus to help him escape the Labyrinth and a golden crown given to her by the god Dionysus. According to the Iliad, she also possessed a dancing floor that the great inventor Daedalus had built for her.[1]

In most traditions, Dionysus honored Ariadne after her death by placing her crown in the heavens as a constellation. This crown—sometimes said to have been fashioned by the craftsman god Hephaestus himself—was made of gold and adorned with precious gemstones.[2] According to an alternative tradition, however, Ariadne never died but was instead granted immortality so that she could live forever on Olympus as Dionysus’ consort.[3]

Some sources imagined Ariadne not on Olympus but in the Underworld. The mythographer known as Hyginus or “Pseudo-Hyginus” even counted her among the “sinful women” (impiae) of the Underworld because she had helped Theseus murder her own brother, the Minotaur.[4]

Iconography

In her earliest known representations (ca. seventh century BCE), Ariadne could be distinguished by the ball of thread that she held. Subsequently, she was commonly represented with Theseus and the Minotaur, or with the Athenian tributes who had accompanied Theseus to Crete (as seen on the François Vase). In both art and literature, Ariadne was also sometimes shown with her famous golden crown.[5]

Roman marble sarcophagus with garlands and the myth of Theseus and Ariadne (ca. 130–150 CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn time, Ariadne began to feature in a greater variety of mythical scenes. After the fifth century BCE, for example, her marriage to Dionysus became a popular subject in Greek and Roman art. One famous painting, the Nekyia of Polygnotus (located in the Lesche of the Cnidians at Delphi), showed Ariadne with her sister Phaedra in the Underworld.[6]

Etymology

The name Ariadne (Greek Ἀριάδνη, translit. Ariádnē) has long been translated as “Most Holy,” deriving from the Cretan word ἄδνος (Greek ἄγνος/ágnos), meaning “holy.”[7] However, some modern scholars argue that the name is actually pre-Greek in origin.[8]

Variant forms of her name include Ἀριήδνη (Ariḗdnē), Ἀρεάδνη (Areádnē), and Ἀριάν(ν)η (Arián(n)ē) in Greek, as well as Ariatha, Areatha, Aratha, and Esia in Etruscan.

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Ariadne Ἀριάδνη (Ariádnē) Phonetic

IPA

[ar-ee-AD-nee] /ˌær iˈæd ni/

Family

Ariadne was the daughter of Minos and Pasiphae,[9] or, alternatively, of Minos and Crete.[10] She was thus the sister of Acacallis, Androgeus, Deucalion, Phaedra, Glaucus, Xenodice, and Catreus, and the half-sister of the Minotaur.

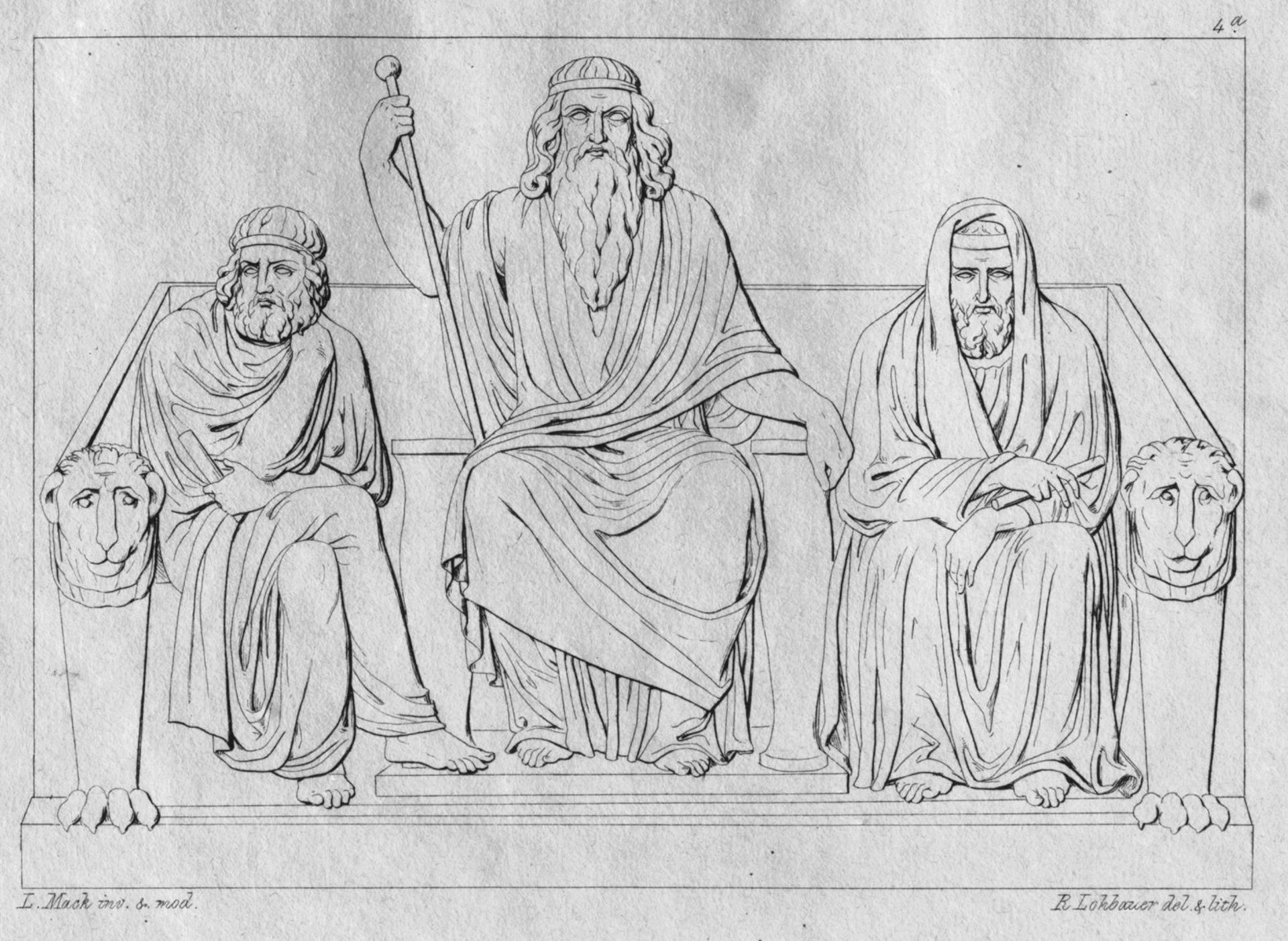

Illustration of the three judges of the Underworld (Minos, Aeacus, and Rhadamanthys) by Ludwig Mack (1829)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFamily Tree

Mythology

Origins

Ariadne’s origins are obscure, but she may have originally been worshipped as a goddess. Some scholars even speculate that she is the “Lady of the Labyrinth” named in some Linear B texts from the Mycenaean period (ca. 1700–ca. 1050 BCE). The myths and rituals surrounding Ariadne bear a resemblance to those of vegetation and fertility deities like Adonis, Hymenaeus, and Hyacinthus.

Ariadne, Theseus, and the Minotaur

In the canonical version of her myth, Ariadne fell in love with the Athenian hero Theseus when he came to Crete. Theseus was one of fourteen tributes (seven male, seven female) that the Athenians were forced to send regularly as offerings to the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull monster. But Theseus vowed to kill the Minotaur, and Ariadne agreed to help him (after making him swear, according to some accounts, that he would marry her afterwards).

The Minotaur by George Frederic Watts (1885).

TatePublic DomainAriadne gave Theseus a ball of thread, which some sources claimed had been given to her by Daedalus, the architect of the Labyrinth. She instructed Theseus to unravel the thread as he passed through the maze-like Labyrinth until he found the Minotaur. That way, after he had killed the monster, he would be able to follow the thread back to the entrance.

Theseus followed Ariadne’s instructions and slew the Minotaur, after which he fled Crete with her and the thirteen other Athenian tributes. Some sources added that he prevented the Cretan ships from pursuing them by cutting holes in their hulls before he left.[24]

However, there are several variants of this myth. According to Diodorus of Sicily, Ariadne merely gave Theseus advice on how to fight the Minotaur,[25] while other authorities claimed that she gave him a gleaming crown—a gift to her from Dionysus—to help him find his way through the dark Labyrinth.[26]

There are also some rationalized versions of the myth. In one account, Theseus killed Deucalion, Minos’ son, after which Ariadne helped him reach a reconciliation with Minos.[27] In another version, Theseus came to Crete to take part in the funeral games of Minos’ son; it was during this visit that he killed Taurus, one of the king’s officers (and the queen’s lover). This feat earned him Ariadne’s love.[28]

Ariadne on Naxos

Sadly, Theseus did not keep his oath to Ariadne. Shortly after fleeing Crete, he abandoned her on the Aegean island of Naxos (called Dia in earlier sources).

Ariadne by Asher Brown Durand, after John Vanderlyn (ca. 1831–1835)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAncient authorities disagreed on why Theseus abandoned Ariadne. Some said that he left her of his own accord, either because he grew tired of her or because he fell in love with another woman.[29] Others countered that it was the gods who caused Theseus to abandon Ariadne, thus allowing Dionysus to marry her (in one account, Dionysus himself simply carried Ariadne away as Theseus slept).[30]

Ariadne was devastated to find that her lover had forsaken her. The Roman poet Catullus imagined her furious lament in detail:

Is it thus, O perfidious, when dragged from my motherland's shores, is it thus, O false Theseus, that you leave me on this desolate strand? thus do you depart unmindful of slighted godheads, bearing home your perjured vows? Was no thought able to bend the intent of your ruthless mind? had you no clemency there, that your pitiless bowels might show me compassion? But these were not the promises you gave me idly of old, this was not what you bade me hope for, but the blithe bride-bed, hymenaeal happiness: all empty air, blown away by the breezes…[31]

It was not long, though, before Ariadne was found by Dionysus, the god of wine and intoxication. Dionysus fell in love with Ariadne (in some traditions, he had already fallen in love with her in Crete) and made her his consort, giving her a gleaming golden crown as a gift.[32]

Illustration of Theseus and Ariadne by Stefano della Bella (1644)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOnce again, there are many variations of this canonical account. In one early version, reported in the Odyssey, Ariadne was killed by the goddess Artemis because of charges brought against her by Dionysus (the exact nature of these charges is not specified).[33]

In another (possibly related) version, Ariadne’s affair with Dionysus began in Crete, before she even met Theseus, meaning that Ariadne was unfaithful to Dionysus when she became Theseus’ lover. This was presumably the crime for which she was punished by Artemis.[34]

Plutarch reports another account (citing Paeon of Amathos) in which Ariadne came not to Naxos but to Cyprus, already pregnant by Theseus. Stormy weather and Ariadne’s weak condition forced Theseus to leave her on the island, where she died before he could return for her. She was buried in a grove that was subsequently dedicated to Ariadne Aphrodite.[35]

In a Naxian version of the myth, there were two Ariadnes. The first one married Dionysus and bore him a son named Staphylus. The second (and later) Ariadne was the one carried off and abandoned by Theseus. She came to Naxos with her nurse Corcyne and eventually died there. The Naxians honored both Ariadnes with festivals: the first Ariadne with a festival of rejoicing, and the second with a festival of mourning.[36]

The Wedding of Bacchus and Ariadne by Guy Louis Vernansal the Elder, formerly attributed to Charles Le Brun (ca. 1709)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainIn a seemingly rationalized alternative, Ariadne lived on Naxos with Oenarus, a priest of Dionysus (as opposed to marrying Dionysus himself).[37]

Death(?)

In most accounts, Ariadne eventually died (she was mortal, after all). Her death greatly grieved Dionysus, who honored her by placing her crown in the heavens as a constellation.[38] However, the details of her demise vary depending on the source.

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca offers a curious explanation for Ariadne’s death. According to this account, Ariadne accompanied Dionysus in his war against Perseus (which began when Argos, Perseus’ city, refused to worship Dionysus). During the fighting, Perseus wielded the head of Medusa, which turned anyone who looked upon it to stone. Ariadne was one of the unfortunate victims of the head’s fatal gaze.[39]

In the end, Dionysus and Perseus made peace, and the Argives agreed to adopt the cult of Dionysus. In some traditions, Dionysus even arranged for Ariadne to be buried in Argos.[40]

In other traditions, Ariadne hanged herself on Naxos after Theseus abandoned her there (and thus never married Dionysus at all).[41]

But not all sources agreed that Ariadne died. According to Hesiod, Dionysus took Ariadne to Olympus after he married her, where “the son of Cronos made her deathless and unageing for him.”[42] Ariadne thus lived forever with the Greek gods.

Worship

Though Ariadne was a prominent figure in Cretan mythology, she had very little cult in ancient Crete. Even so, her cult was important on a number of other Aegean islands.

In Naxos, local tradition knew of two Ariadnes (see above), each with her own festival. The festival of the first Ariadne, the wife of Dionysus, was a joyful occasion marked by reveling and celebration, while the festival of the second Ariadne, who had been abandoned by Theseus, was marked by mourning.[43] The young maidens (parthenoi) of Naxos would dance in Ariadne’s honor.[44]

The people of Cyprus, on the other hand, had their own local traditions about Ariadne, who they said had been abandoned by Theseus on their island. Here Ariadne was connected with Aphrodite, appearing as the figure Ariadne Aphrodite; in this guise, she had a sacred grove that contained her tomb. In one strange ritual in honor of Ariadne, a young man would lie on the ground and imitate the cries of a woman in labor.[45]

Marble statue of Pan, Aphrodite, and Eros (ca. 100 BCE). Aphrodite threatens Pan with a sandal as he makes advances towards her, while a winged Eros plays with Pan’s horns.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / Helen SimonssonCC BY-SA 2.0On the island of Delos, Ariadne was connected with Apollo. A small cult image (xoanon) of Aphrodite, clearly very old, was said to have been dedicated at the Delian Temple of Apollo by Theseus, who had received the artifact from Ariadne. She in turn had received it from its maker, the great artist Daedalus.[46]

A few sacred sites of Ariadne were known in mainland Greece as well. In Argos, there was an alleged tomb of Ariadne within the sanctuary of Apollo Kresios, the “Cretan” Apollo.[47] One tradition claimed that Ariadne also received cult honors in Locris, though this is more dubious.[48]

Ariadne may have been behind the “sacred marriage” ritual that took place in Athens on the Choes, the second day of the springtime Anthesteria festival. During this ritual, the Archon Basileus (“King Archon”) ceremonially gave his wife (the Basilinna, or “Queen”) in marriage to Dionysus. This was likely a reenactment of the myth in which Theseus gave up Ariadne so that Dionysus could have her.[49]

Ariadne appears to have been adopted early on by the Etruscans of northern Italy, who knew her as Ariatha, Areatha, Aratha, or Esia. In Etruscan art, she was depicted as the consort of Fufluns, the Etruscan equivalent of Dionysus. However, it is unclear to what extent she was worshipped alongside Fufluns.

Popular Culture

Ariadne remains a fixture in modern Western culture. She is remembered especially for her ball of thread, which she gave to Theseus to help him escape the Labyrinth. This ball of thread has increasingly become a symbol for puzzles and mysteries that can be solved in more than one way.

Ariadne has also retained her importance in literature and the arts. She is especially prominent in opera, as seen in works by Claudio Monteverdi, Joseph Haydn, and Richard Strauss, among others. As a literary figure, Ariadne appears in a poem by Friedrich Nietzsche (“Ariadne’s Lament,” one of the poems collected in the Dionysian Dithyrambs) and in a short epic poem by F. L. Lucas (titled simply Ariadne).

More recently, Ariadne has appeared in several novels. Important examples include Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, a historical bildungsroman based on the myths of Theseus, which casts Ariadne as a major character; Madeline Miller’s Circe, where Ariadne has a minor role; and Jennifer Saint’s Ariadne, a retelling of Ariadne’s myth from her perspective (rather than from Theseus’).

Ariadne has been important in film and television as well. In the 2010 film Inception, Ariadne (played by Elliot Page) is an architecture student who designs labyrinth-esque dream worlds. The motif of Ariadne’s thread has also featured in cinema and television, including in the German series Dark. Finally, the mythical Ariadne can be seen in the BBC series Atlantis (2013), where she is played by Aiysha Hart.