Greek Heroes

Black-figure hydria showing the fight of Achilles and Memnon (ca. 575–550 BCE)

The Walters Art MuseumCC0Overview

The Greek heroes were a group of especially notable or superhuman mortals whose achievements defined the mythical Age of Heroes. In Greek religion, they were often given cult honors after their death and worshipped in “hero cult.”

The Greek concept of “hero” is difficult to pin down. In antiquity, the term was used differently in different contexts: it could refer to distinguished warriors, important historical figures, founders of cities, notable inventors, or revered ancestors who received cult honors.

What does the word “hero” mean?

The ancient Greek word hḗrōs (ἥρως) did not always have a consistent meaning, even in antiquity. The term was once thought to be etymologically related to the name of the Greek goddess Hera, but this view has been increasingly challenged or rejected.

In religious contexts, the Greeks used the term “hero” to refer to powerful figures who received cult honors after their death; this is what is known as “hero cult.” But in Greek culture more broadly, the term was also applied to distinguished mortals from mythology, especially great warriors and those who fell in battle.

Combat Between Greeks and Trojans by Sebald Beham (1518–1530)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWho were the most famous Greek heroes?

Greek mythology features a wide range of heroes. Some of the greatest heroes, including Heracles, Perseus, and Bellerophon, made a name for themselves as monster-slayers. Other heroes led famous expeditions, such as the voyage of the Argonauts, led by Jason, or the Calydonian Boar Hunt, led by Meleager.

Many other Greek heroes achieved fame and glory in war. Achilles, Odysseus, and Hector, for example, distinguished themselves during the Trojan War.

The Wrath of Achilles by François-Léon Benouville (1847)

Musée Fabre, MontpellierPublic DomainWhich Greek heroes visited the Underworld?

Only a few Greek heroes managed to visit the Underworld and make it back to the land of the living. The most famous mortal visitor was probably Heracles, the strongest of the Greek heroes. He traveled to the Underworld to fetch Cerberus, the guard dog of Hades, as one of his Twelve Labors.

Other heroes who journeyed to the Underworld included the musician Orpheus, who sought to retrieve his dead wife Eurydice, as well as the Athenian king Theseus, who came on a less noble mission: to abduct Persephone, Hades’ queen.

Pluto and Cerberus, after Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (early 17th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThe Heroes of the Trojan War

The Trojan War represented the greatest assemblage of heroes from Greek mythology. The war began when Paris, one of the princes of Troy, carried off Helen, the wife of the Spartan king Menelaus.

Menelaus raised a vast army to retrieve his wife, made up of heroes from all the cities of Greece. This army was led by Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae. Also included in the Greek ranks were warriors such as Achilles, the greatest fighter of his generation; Odysseus, the wily king of Ithaca; Ajax “the Greater,” a fantastically strong warrior from Salamis; and Diomedes, the king of Argos and a favorite of Athena.

The Trojans had many famous heroes on their side, too. Their greatest warrior was Hector, eldest son of the king and the commander of Troy’s forces. Other Trojan heroes included Aeneas, who would later become the ancestor of the Romans; Trojan princes such as Deiphobus, Paris, and Helenus; and foreign allies such as Sarpedon, Penthesilea, and Memnon.

The Trojan War thus became a spectacular showdown between the heroes of Greece and the heroes of the East. After ten years, the Greeks finally prevailed and sacked Troy, but only after losing many of their greatest heroes in the struggle. Depleted, the Greeks returned home. They were to be the last generation of the Age of Heroes.

The Burning of Troy by Johann Georg Trautmann (18th century)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainList of Notable Greek Heroes

There were many figures (most of them mythical) whom the Greeks honored as heroes. Some were local individuals who were little known outside of their own city-state or region. But the most famous Greek heroes were known to all Greeks, featuring in mythical narratives immortalized in literature and art.

The list below names some of the most notable heroes of Greek mythology, including great warriors as well as artists, healers, and founders of cities.

Achilles

Achilles, son of Peleus and Thetis, was the greatest of the heroes who fought at Troy. Though destined to die young, he achieved much fame and glory during his short life, killing Hector and many other Trojan champions during the Trojan War.

In the final year of the Trojan War, Achilles was killed by Paris with the help of the god Apollo. But many poets claimed that Achilles did not descend to the Underworld; instead, he enjoyed a blissful afterlife in the Isles of the Blessed.

Attic red-figure hydria showing Ajax and Achilles playing, attributed to the Berlin Painter (ca. 490 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAeneas

Aeneas, son of Aphrodite and Anchises, was one of the strongest Trojan heroes who fought against the Greeks during the Trojan War. After his city fell, Aeneas escaped with a band of refugees and sailed west; the Romans later adopted him as their mythical ancestor, claiming that he founded a new kingdom in Italy.

Aeneas is best known today from Roman literature, especially Virgil’s Aeneid, where he flees Troy with his family and household gods and suffers many trials on his way to Italy. Romulus, the founder and first king of Rome, was said to have been a descendant of Aeneas. The Romans also identified Aeneas with the local Latin god Indiges (or Jupiter Indiges).

Aeneas' Flight from Troy by Federico Barocci (1598)

Borghese Gallery, RomePublic DomainAgamemnon

Agamemnon, son of Atreus, was the king of Mycenae and the leader of the Greek army during the Trojan War.

Agamemnon went to great (and often ruthless) lengths to conquer Troy, even sacrificing his own daughter Iphigenia in exchange for a wind that would blow the Greek fleet to its destination. During the war, he often clashed with Achilles; one particularly vicious quarrel resulted in Achilles withdrawing from the war for a fateful period.

After ten grueling years, Agamemnon finally sacked Troy. Upon returning home, however, he was slaughtered by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus.

Gold death mask known as the "Mask of Agamemnon" (ca. 1550–1500 BCE), discovered in Mycenae by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876

National Archaeological Museum of Athens / Xuan CheCC BY 2.0Asclepius

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was a physician who was promoted to the rank of hero and even came to be regarded as a full-fledged god. He was killed by Zeus when he used his healing abilities to restore a dead man to life, thus challenging the divine order.

Unusually for a hero, Asclepius was worshipped as a god in ancient Greece. As the god of healing, he had temples throughout the Greek world, with a particularly important cult center at Epidaurus.

Statue of Asclepius, Roman copy (ca. 160 CE) after a 4th-century BCE Greek original, from the Temple of Asclepius at Epidaurus

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / MarsyasCC BY-SA 3.0Atalanta

Atalanta, a female hero connected with either Arcadia or Boeotia, proved herself more than equal to her male counterparts. A skilled hunter and warrior, she distinguished herself among the Argonauts and drew first blood during the Calydonian Boar Hunt.

One famous myth told of how Atalanta would only marry a man who could best her in a footrace. Though no living man could rival Atalanta in speed, one of Atalanta’s suitors did finally beat her using trickery. The two were wed, but Atalanta and her new husband upset the gods by profaning one of their temples; as punishment, they were transformed into lions.

Hippomenes and Atalanta by Guido Reni (1618–1619).

Prado MuseumPublic DomainBellerophon

Bellerophon, son of Poseidon, was a formidable monster-slayer. Though he hailed from Corinth, he traveled widely throughout Greece and Asia, taming the winged horse Pegasus and battling the monstrous Chimera and other fearsome foes.

Bellerophon became a cautionary tale, however, when he succumbed to hubris and attempted to storm the home of the gods on Mount Olympus. As he was ascending to the heavens atop Pegasus, the gods caused him to fall to the earth, where he lived the rest of his life as a cripple.

Bellerophon is Sent to the Campaign against the Chimera by Alexander Ivanov (1829)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainCadmus

Cadmus was an Eastern prince who left his home as a young man to search for his sister Europa, who had been abducted by Zeus. Failing to find Europa, Cadmus settled in Greece and founded the city of Thebes. There he married Harmonia and had many children by her.

Cadmus ruled as king of Thebes for many years. But when he and his city failed to acknowledge the divinity of the new god Dionysus—the son of Cadmus’ own daughter Semele—Cadmus suffered a grievous punishment: he and his wife were turned into snakes and forced to roam Greece at the head of a barbarian army.

Cadmus Sowing the Dragon's Teeth by the workshop of Peter Paul Rubens (between 1636 and 1700)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainDiomedes (son of Tydeus)

Diomedes, son of Tydeus, was a ruler of Argos. He was one of the leaders in the war of the Epigoni and later fought with the Greeks in the Trojan War.

When Diomedes finally returned home from Troy, he learned that his wife Aegialea had been unfaithful to him and was plotting his destruction. Forced to flee his home, he ultimately settled in Italy, where he founded several cities. He was worshipped as a god following his death.

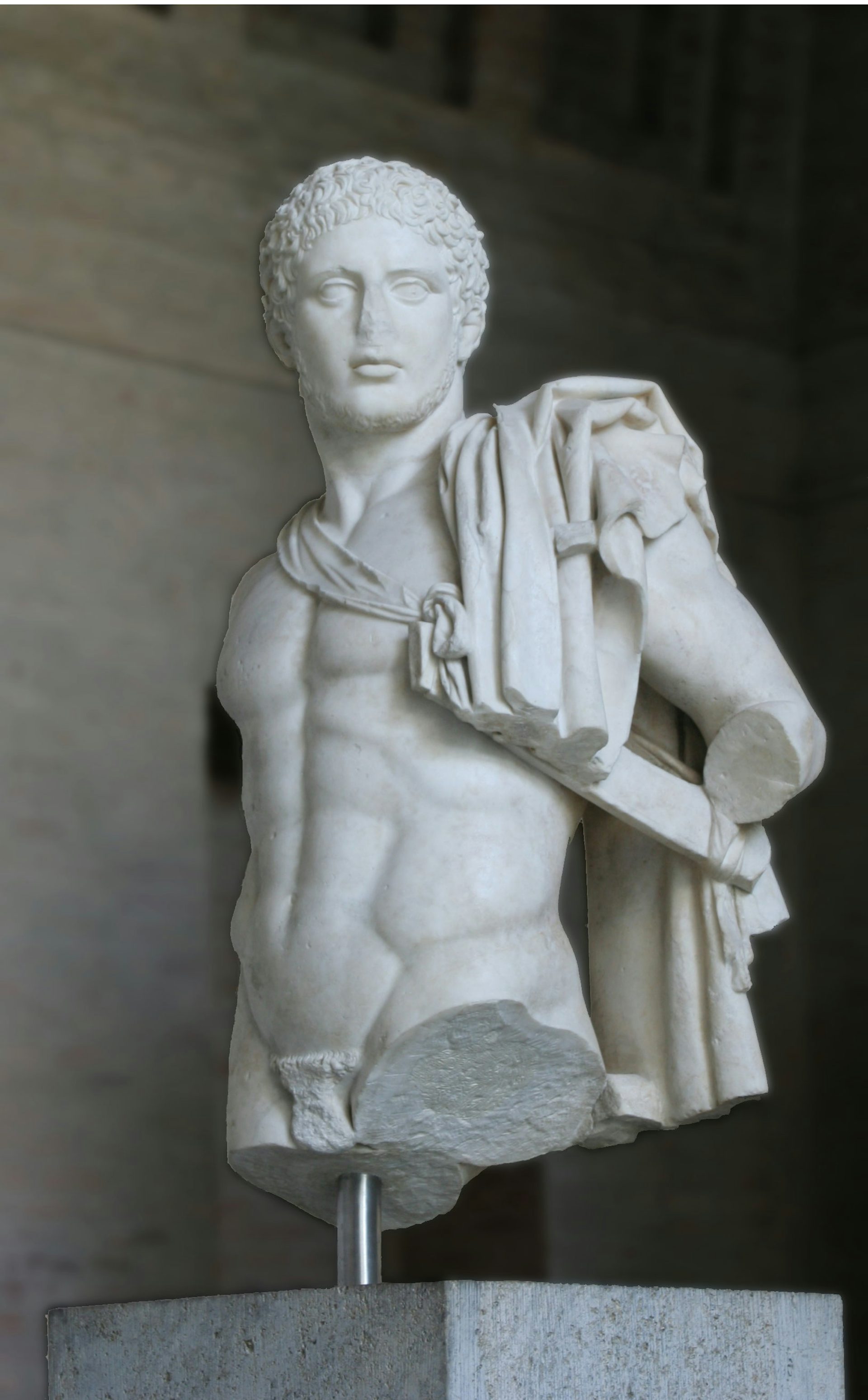

The "Munich Diomedes," a Roman copy after a Greek original by Kresilas (ca. 440–430 BCE)

Glyptothek, Munich / MatthiasKabelCC BY-SA 3.0Dioscuri

Castor and Polydeuces, often known as the Dioscuri, were the sons of either Tyndareus, the king of Sparta, or Zeus, the king of the gods. They grew into some of the greatest heroes of their time, taking part in such exploits as the voyage of the Argonauts and the Calydonian Boar Hunt.

The Dioscuri were killed in battle by Idas and Lynceus, twin brothers from Messenia who were their chief rivals. But Zeus granted them partial immortality: they alternated between living among the gods on Olympus and living among the dead in the Underworld. The Dioscuri were widely worshipped as gods throughout the Greek world.

Leda and the Swan by Jacques Sarazin (ca. 1640–1650)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHector

Hector was a Trojan hero and prince—the eldest son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy. He was a loving husband to his wife Andromache and a devoted father to his young son Astyanax.

Hector fought bravely against the Greeks during the Trojan War. In fact, he nearly succeeded in driving them from Troy entirely when Achilles, the Greeks’ champion, withdrew from the fighting during the ninth year of the war. But Hector made the mistake of killing Achilles’ best friend Patroclus in battle. Devastated, Achilles fought Hector outside the walls of Troy and killed him.

Hector Admonishes Paris for his Softness and Exhorts him to Go to War by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1786)

Augusteum, OldenburgPublic DomainHeracles

Heracles was a son of Zeus, best known for performing the Twelve Labors. Noted for his physical strength and heightened masculinity, he was usually depicted wearing a lion skin and wielding a giant club.

Heracles was probably the most prolific of the Greek heroes, taking part in numerous heroic exploits. The most famous of these were the Twelve Labors that he performed for his cousin Eurystheus, the king of Mycenae.

Throughout his life, Heracles suffered greatly due to the hatred of his stepmother Hera. In one myth, Hera even caused Heracles to murder his own family. Heracles himself was prone to violent anger and lust—characteristics that would ultimately lead to his downfall.

It was said that Heracles became a god after his death. Indeed, Heracles was one of the few mortal heroes to be worshipped as a full-fledged god (rather than as a dead hero) by the ancient Greeks. His cult was especially important in Thebes and in Dorian cities such as Sparta.

Hercules and the Hydra by Antonio del Pollaiolo (ca. 1475).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainJason

Jason, son of Aeson, was a Greek hero from Iolcus. He is most famous for leading the Argonauts in their quest to steal the Golden Fleece from the Colchian king Aeetes. In this mission, Jason received help from the beautiful witch Medea, Aeetes’ daughter.

After acquiring the Golden Fleece, Jason married Medea, and the two returned to Greece. But the couple were banished from Iolcus for murdering Pelias, Jason’s uncle. Later, Jason abandoned Medea to marry a younger woman, but Medea took a terrible revenge: she killed Jason’s new bride as well as the children that she herself had borne to Jason.

Medea Rejuvenating Aeson by Corrado Giaguinto (ca. 1760)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainMeleager

Meleager, son of Oeneus, was a prince of Calydon in Aetolia. A powerful warrior, an Argonaut, and (according to some traditions) the lover of the heroine Atalanta, Meleager was best known for his role in the Calydonian Boar Hunt.

Meleager led the hunt to kill the monstrous Calydonian Boar, which had been sent by Artemis to terrorize the local countryside. After the hunt, Meleager and his uncles quarreled over the spoils taken from the boar; the quarrel turned violent, and Meleager ended up killing his uncles. Meleager’s mother Althaea was so angry when she found out that she killed her own son by burning up an enchanted log.

Meleager Killing the Calydonian Boar by Theodoor Boeyermans (1677)

Musée de la chasse et de la nature, ParisPublic DomainMenelaus

Menelaus was the son of Atreus and the younger brother of Agamemnon. He became king of Sparta when he married Helen, foster daughter of the Spartan king Tyndareus.

When Helen abandoned Menelaus to run off with the Trojan prince Paris, Menelaus and Agamemnon raised an army to bring her back. This incited the decade-long Trojan War, which ended with the destruction of Troy and Helen’s return to Menelaus.

Menelaus went home to Sparta, and he and Helen lived the rest of their lives as husband and wife. They were said to be buried at Therapnae, near Sparta, where they were later worshipped.

Roman statue of Menelaus holding the body of Patroclus (or Achilles holding the body of Achilles), 1st century CE copy after a Greek original from the 3rd century BCE

Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence / Mary HarrschCC BY-SA 4.0Odysseus

Odysseus, son of Laertes and Anticlea, was king of the island of Ithaca. He married Penelope and had one son by her, Telemachus.

Described by Homer as “the man of twists and turns” and favored by the goddess Athena, Odysseus was a hero of great intelligence and cunning. He played an instrumental role in the Trojan War: it was Odysseus who devised the trick of the Wooden Horse (now known as the Trojan Horse) to help the Greeks penetrate Troy’s impregnable walls and conquer the city.

After sacking Troy, Odysseus spent ten years wandering the world as he tried to get back home to Ithaca. These wanderings are the most famous part of his mythology and are full of fantastic adventures: the hero faced Cyclopes, sorceresses, and sea monsters, among other creatures and foes, before finally reaching Ithaca and reuniting with his family.

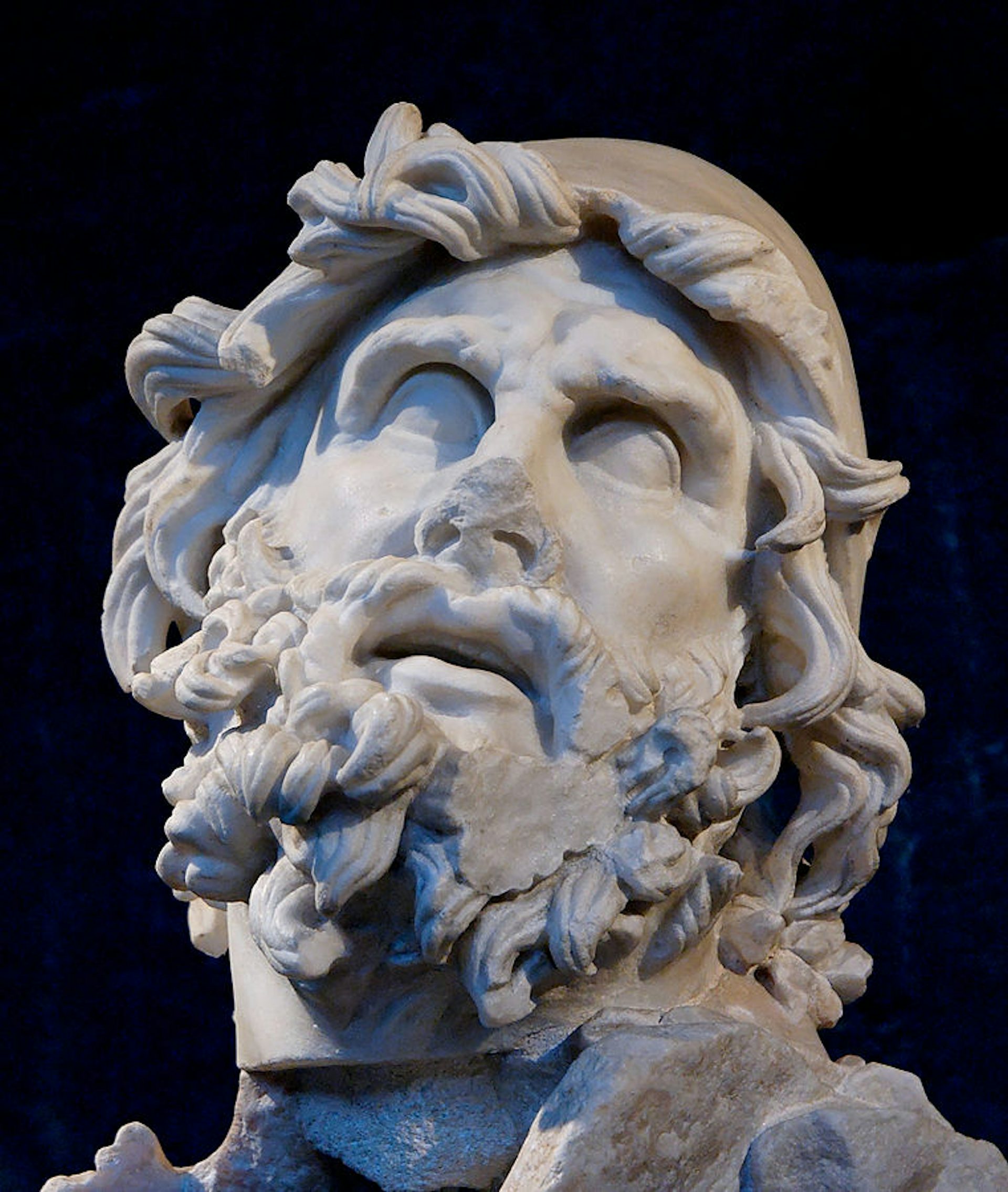

Head of Odysseus from a sculptural group of the blinding of Polyphemus from the Villa of Tiberius at Sperlonga (1st century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Sperlonga / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainOedipus

Oedipus was the son of Laius, a king of Thebes, and his wife Jocasta (or Epicasta, according to some sources). He was left for dead as an infant because of an ominous prophecy, but was discovered by a herdsman and raised by the Corinthian king Polybus.

Upon reaching adulthood, Oedipus learned that he was destined to kill his father and marry his mother. The hero was naturally horrified by this news and did everything in his power to avoid his fate. Unfortunately, this only led him to inadvertently fulfill the prophecy.

After running away from home, Oedipus quarreled with and killed an old man, defeated the Sphinx, and became the king of Thebes by marrying the widow of the late king. Oedipus soon discovered, however, that the old man he had killed on his travels was none other than his true father, Laius, and that the woman he had married was his mother, Jocasta. Horrified, Oedipus blinded himself and went into exile.

Oedipus Separating from Jocasta by Alexandre Cabanel (1843)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainOrpheus

Orpheus was the great musician of Greek mythology, whose songs were endowed with miraculous and superhuman powers. The son of the Thracian mortal Oeagrus (or the god Apollo), Orpheus became a noted musical innovator and religious figure.

In myth, Orpheus helped the Argonauts on their mission to steal the Golden Fleece. But he was best known for his tragic love of Eurydice. When Eurydice died on the eve of her wedding to Orpheus, the musician went to the Underworld in an attempt to get her back; when he failed in this quest, Orpheus spent the rest of his life in mourning until he was torn apart by either Thracian women or maenads.

Orpheus was honored as an important mythical hero and the spiritual father of all musicians. As a religious figure, he was closely associated with several mystery cults, especially the Orphic Mysteries.

Orpheus by George de Forest Brush (1890).

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainPerseus

Perseus, the mortal son of Zeus and the Argive princess Danae, was a Greek hero, king, and slayer of monsters.

Expelled from Argos (along with his mother), Perseus was raised on the island of Seriphos. He made a name for himself by killing the Gorgon Medusa and later rescuing the princess Andromeda. After returning to the Argolid, he founded the city of Mycenae, where he established the Perseid dynasty.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa by Antonio Canova (1804–1806)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainTheseus

Theseus, son of Aethra and Aegeus (or possibly Poseidon), was the foremost hero and king of mythical Athens. He accomplished both heroic exploits, such as killing the Minotaur, and impressive political feats that cemented Athens as a regional power.

Theseus’ life, however, was not without its disappointments and grief; he could be thoughtless or hasty, often with devastating results. For example, his failure to follow his father Aegeus’ instructions when he came back from Crete caused Aegeus’ death, and his quick temper cost him the life of his son Hippolytus.

Despite his flaws, the Athenians revered Theseus above all other heroes.

Theseus and Aethra by Laurent de La Hyre (ca. 1635–1636)

Museum of Fine Arts, BudapestPublic DomainTriptolemus

Triptolemus was an Eleusinian prince and hero. He was known for teaching the art of agriculture to the nations of the world, having learned this art from the goddess Demeter herself. Triptolemus traveled around the world in a flying chariot drawn by serpents or dragons, also given to him by Demeter.

Triptolemus was revered as an important Attic hero, receiving cult honors at Eleusis.

Ceres Teaching Agriculture to King Triptolemus by Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée (1769)

Palace of VersaillesPublic DomainAttributes

The heroes were a loosely defined class of venerated dead mortals. The most familiar Greek heroes were mythical ancestors, though certain historical figures, such as lawgivers or athletes, were also honored as heroes after they died.

The Greeks saw the heroes as transitional figures, straddling the middle ground between gods and humans (comparable to other semi-divine beings, such as daemons). Hesiod called the heroes hēmítheoi (ἡμίθεοι), or “demigods.”[1]

The Age of Heroes was transitional, too, standing between an earlier period in which gods and immortal giants inhabited the world and the later Age of Iron, defined by toil and corruption. After the Greek heroes died out, many were granted a blissful afterlife in the Field of Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed.[2]

Though each Greek hero was distinct, they tended to share certain characteristics. They were always mortal, though many had a divine parent or ancestor; they were almost always distinguished by their remarkable valor and military accomplishments; many were great inventors or founders of cities; and they were usually closely associated with death, boasting famous tombs or distinctive myths about their demise.

Elysian Fields by Arthur B. Davius (19th/20th century)

The Phillips Collection, Washington, DCPublic DomainDespite these shared qualities, an exact definition of the Greek hero remains elusive. Indeed, we must distinguish between the religious definition of the term and the literary or mythological one.[3]

The religious definition is relatively straightforward: a hero was anybody who received worship through hero cult.[4] In this capacity, heroes were looked upon as powerful and even semi-divine ancestors who could act as benevolent helpers (or dangerous avengers) of their living descendants.

The heroes with the widest appeal—most notably Heracles—were regarded as Panhellenic (that is, common to all the Greeks), while others were more local. But heroes rarely became full-fledged gods, except in extraordinary cases; the only ones to ever ascend to the level of the gods were Asclepius, the Dioscuri, and Heracles.

This religious definition of the hero, however, does not always align with how the term was used in ancient mythological texts; it is at once too broad and too narrow. On the one hand, there were many Greek mythical figures who were recipients of hero cult, yet who failed to exhibit the typical qualities of the hero (divine parentage, military accomplishments, etc.). On the other hand, some mythical figures who did display typical heroic qualities do not seem to have enjoyed a hero cult.

Over the years, various scholars have attempted to classify or categorize the wide range of Greek heroes. In a still influential work published in 1921, Lewis Richard Farnell identified seven categories of hero cult in the ancient Greek world:[5]

1. Heroes and heroines of divine origin or “hieratic” type—figures “with ritual legends or associated with vegetation ritual.” These heroes essentially represented faded gods. In other words, they were probably originally worshipped as gods but later came to be seen as heroes instead.

Roman marble sarcophagus with garlands and the myth of Theseus and Ariadne (ca. 130–150 CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainExamples of hieratic heroes include Ariadne—a Cretan princess connected with the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur who seems to have once been a local goddess of vegetation—and the Boeotian Aristaeus, who seems to have originated as a god of livestock.

2. “Sacral” heroes and heroines—figures who served as priests, prophets, or companions of a particular deity. Examples include Iphigenia—closely connected with the goddess Artemis in myth as well as cult—and mythical seers such as Melampus and Cassandra.

3. Secular figures who eventually became fully deified. These were very rare in Greek mythology and religion; the only significant examples are Heracles, Asclepius, and the Dioscuri.

4. Heroes of epic and saga. Key examples include Achilles and Agamemnon, who are major figures in Homer’s epics.

Apulian red-figure volute krater showing Chryses trying to ransom his daughter Chryseis (left) from Agamemnon (right) by the Painter of Athens 1714 (ca. 360–350 BCE). From Taranto, Italy.

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic Domain5. “Mythic ancestors, eponymous heroes, and mythic oecists [city-founders],” such as Aeolus (the mythical ancestor and eponym of the Aeolians), Ion (the mythical ancestor and eponym of the Ionians), and so on.

6. Functional and culture heroes. These were often obscure “Sondergötter”—that is, deities who were limited to a single constrained function. Examples include figures such as Muiagros (“Fly-Catcher”) and Kyamites (“Bean-Man”).

7. Real and historic persons who were granted the status of hero after they died. These included many great lawgivers, politicians, and athletes who were celebrated for their achievements.

Another scholar, Angelo Brelich, approached the problem somewhat differently. He posited nine fundamental themes from which all heroic myths and hero cults are constituted.[6] These themes are:

Death

Warfare

Athletics

Prophecy

Healing

Mysteries

Rites of passage

Founding of cities

Kinship

None of these definitions are without problems. Farnell’s categories, for example, sometimes lead to overlap or result in certain figures being arbitrarily listed in one category rather than another. Brelich’s nine heroic themes, meanwhile, have often been regarded by scholars as overly restrictive. But these attempts at classification still provide a helpful framework for thinking through the highly complex concept of the hero in ancient Greece.

Etymology

The Greek word “hero” (Greek ἥρως, translit. hḗrōs) is very ancient, well known by the time of Homer. The term may even date back to the Mycenaean period (ca. 1700–1050 BCE): the phrase ti-rise-ro-e, “three times a hero,” has been found on tablets written in Linear B, the syllabic script used before the alphabet was adopted in Greece.[7]

Attic red-figure hydria showing Ajax and Achilles playing, attributed to the Berlin Painter (ca. 490 BCE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainPronunciation

English

Greek

Hero, Heroine ἥρως (hḗrōs; pl. ἥρωες/hḗrōes) ἡρωῖνα/ἡρώισσα, (hērōîna/hērṓissa; pl. ἡρωῖναι/ἡρώισσαι/hērōînai/hērṓissai) Phonetic

IPA

[HEER-oh], [HER-oh-in] /ˈhɪər oʊ/, /ˈhɛr oʊ ɪn/

Mythology

Origins

The origins of the hero figure are obscure, much like the term itself. Though the phrase “three times a hero” dates back to the Mycenaean period (ca. 1700–1050 BCE; see above), this expression does not tell us much about what a hero was during that time. It is possible that the term was somehow related to ancestor cults, such as the Tritopatores (“triple fathers”), known from various parts of the Greek world.

Direct archaeological evidence for heroes and hero cult only goes back to about the eighth century BCE. The Greeks tended to connect their heroes with anonymous monumental graves, many of them from the Bronze Age; however, this may simply be due to the fact that these graves were large and impressive and housed bodies whose true identities had long been forgotten.

Scholars have sought a variety of explanations for where heroes and hero cults came from. Some have tried to trace the Greek heroes and their worship to an ancestor cult practiced by the Mycenaeans, while others have connected the heroes with rites of initiation.

The "Warrior Vase," a painted Mycenean krater (12th century BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, Athens / Sharon MollerusCC BY 2.0Unfortunately, none of these theories can be confirmed with the available evidence. It may well be that the Greek heroes and their cult had several different origins, with some heroes representing ancestor cult, others originating as local gods, others coming from epic, and so on.

The Age of Heroes

Traditionally, the Greek heroes lived during a remote mythical period, sometimes known as the Age of Heroes.

In the so-called Myth of the Ages—best known from Hesiod’s Works and Days—we hear of five ages of mortals: the race of the first age was made of gold and lived a life of bliss until they died out peacefully; the race of the second age was made of silver and lived a life of sin until the gods destroyed them; the race of the third age was made of bronze and led a warlike existence until they destroyed themselves; the fourth age was the age of the half-divine heroes; and the race of the fifth age was made of iron—weak, unjust beings plagued by suffering.[9]

Though Hesiod expressed nothing but contempt for his own age (the Age of Iron), he spoke highly of the previous Age of Heroes. He described the heroes as godlike and half-divine, claiming that they performed numerous mighty feats before being killed off in the great wars of Greek myth:

Grim war and dread battle destroyed a part of them, some in the land of Cadmus at seven-gated Thebes when they fought for the flocks of Oedipus, and some, when it had brought them in ships over the great sea gulf to Troy for rich-haired Helen's sake: there death's end enshrouded a part of them.[10]

After all the heroes had died, the gods honored them for their achievements by placing them in Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed, where they could enjoy eternal ease and comfort.

Deucalion and Pyrrha by Peter Paul Rubens (1636)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainOther ancient sources specified that the heroes lived between the time of Deucalion’s flood—which Zeus had sent to wipe out an earlier sinful race of human beings—and the end of the Trojan War.

Heroic myths generally centered on the achievements of the often-superhuman figures who lived during these remote periods.

Many heroes won fame for killing monsters. Perseus, for example, killed the Gorgon Medusa, who turned all those who looked upon her to stone; Bellerophon killed the fire-breathing hybrid monster known as the Chimera; and Heracles—perhaps the most prolific monster-slayer in all of Greek mythology—fought and defeated numerous creatures, including the Nemean Lion, the Hydra, and Cerberus.

Other heroes were known for founding cities, kingdoms, or dynasties. Cadmus, an Eastern prince, was one of the founding figures of Thebes; Perseus, slayer of Medusa, founded the city of Mycenae and established the important Perseid dynasty. Other figures, such as Aeolus or Ion, were “eponymous” heroes who gave their names to their descendants (thus, Aeolus’ descendants were called Aeolians, Ion’s descendants Ionians, and so on).

Some heroes were inventors or innovators. Asclepius, who was both a hero and a god, was the most important physician of Greek mythology. Other figures, such as the Boeotian Aristaeus or the Attic Triptolemus, were important inventors or teachers connected with the agrarian and agricultural sphere.

The Offering to Asclepius by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1803)

Museum of Fine Arts, ArrasPublic DomainMany other heroes participated in the heroic expeditions described in the Greek epics. Some of the most important of these were the voyage of the Argonauts (led by Jason), the Calydonian Boar Hunt (led by Meleager), the Theban Wars (i.e., the war of the Seven against Thebes and the war of the Epigoni), and, of course, the Trojan War.

The figures involved in the Trojan War—including Achilles, Agamemnon, Hector, and Odysseus—represented the last great generation of mythical heroes. According to Hesiod and other poets, the heroes died out after the Trojan War, a grueling conflict that claimed the lives of many of Greece’s greatest warriors.

In other sources, the Age of Heroes ended when Heracles’ descendants (the “Heraclids”) invaded and overran Greece.

Worship

Sanctuaries

Hero cults were generally centered on the tomb of the dead hero and thus had a very local character. These tombs were often situated on the boundary of a settlement. The tomb of Heracles’ nephew Iolaus, for example, was located at one of the gates of Thebes.[11] From privileged positions such as this, the dead hero was thought to offer protection.

In other cases, the tomb of the hero was located inside the boundary of the settlement. In particular, the tombs of founding heroes, such as Cadmus in Thebes, were generally located at the center of the city, in the agora (“marketplace”).

Cadmus Killing the Dragon by Léon Davent, after Francesco Primaticcio (ca. 1540–1545)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHeroes’ sanctuaries were characteristically smaller and less impressive than those of the gods. Some were no more than small demarcated spaces within the larger precinct of a god—for example, the shrine of the hero Pelops within the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia, or that of Neoptolemus within the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. On the other hand, some heroes—such as Hippolytus at Troezen—boasted substantial sanctuary complexes, comparable to those of the gods.

Rituals

The rituals associated with hero cult could vary widely. Heroes were sometimes honored with “Olympian” sacrifices—that is, sacrifices of light-colored victims, made on elevated altars. A few of the most important Panhellenic heroes, including Heracles, Asclepius, and the Dioscuri, were sometimes even regarded as equals of the gods.

Roman statuettes of Castor and Pollux (1st half of the 3rd century CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Ad MeskensCC BY-SA 3.0But many individual heroes had more specific rites that bore a closer resemblance to the rites of the chthonic gods. (This makes sense, as the dead heroes were commonly imagined living beneath the earth, in the domain of the chthonic gods of the Underworld.) These rites, closely associated with death, tended to take place at night and involved the burning up of dark-colored victims on low altars or in pits.

Other heroes were invoked via magic. These heroes were often dangerous and dark figures, rather than helpful deities, and the purpose of their cult was to appease their anger. In Temesa, for example, a Greek city in southern Italy, it was thought that a nameless local hero would wreak havoc if he did not receive a new bride to deflower every year.[12]

Heroine Cult

There is less that can be said with certainty about the worship of female heroes, or “heroines.” In many cults, a heroine (who was often nameless) would serve as the wife of the local hero. In some cases, the heroine was part of an entire family constructed around the central male hero.

For example, the cult of Asclepius, who was a hero as well as a god, also encompassed his wife Epione and his daughters, who represented various medical personifications: Hygieia (“Health”), Iaso (“Healer”), Panacea (“Cure-All”), and so on.

Some heroines, however, were worshipped independently rather than as the consorts of male heroes. Such heroines were usually connected to all-female cults, such as the cult of Iphigenia at Brauron.

Photo of the remains of the Temple of Artemis at Brauron

PanosinkentCC BY-SA 4.0Popular Culture

The idea of the hero has taken on a life of its own. Today the term is hopelessly polysemous, having many different meanings.

Some scholarly attempts to classify the hero have become quite popular. Particularly well known is Joseph Campbell’s discussion of the “hero’s journey” (or the “monomyth”), a narrative pattern in which the hero faces and triumphs over a crisis, then returns home somehow transformed.

In Western culture especially, a hero has increasingly come to be seen as a character who fights adversity using virtues such as courage, intelligence, and integrity. The term is often used to describe the protagonist of a novel or film.

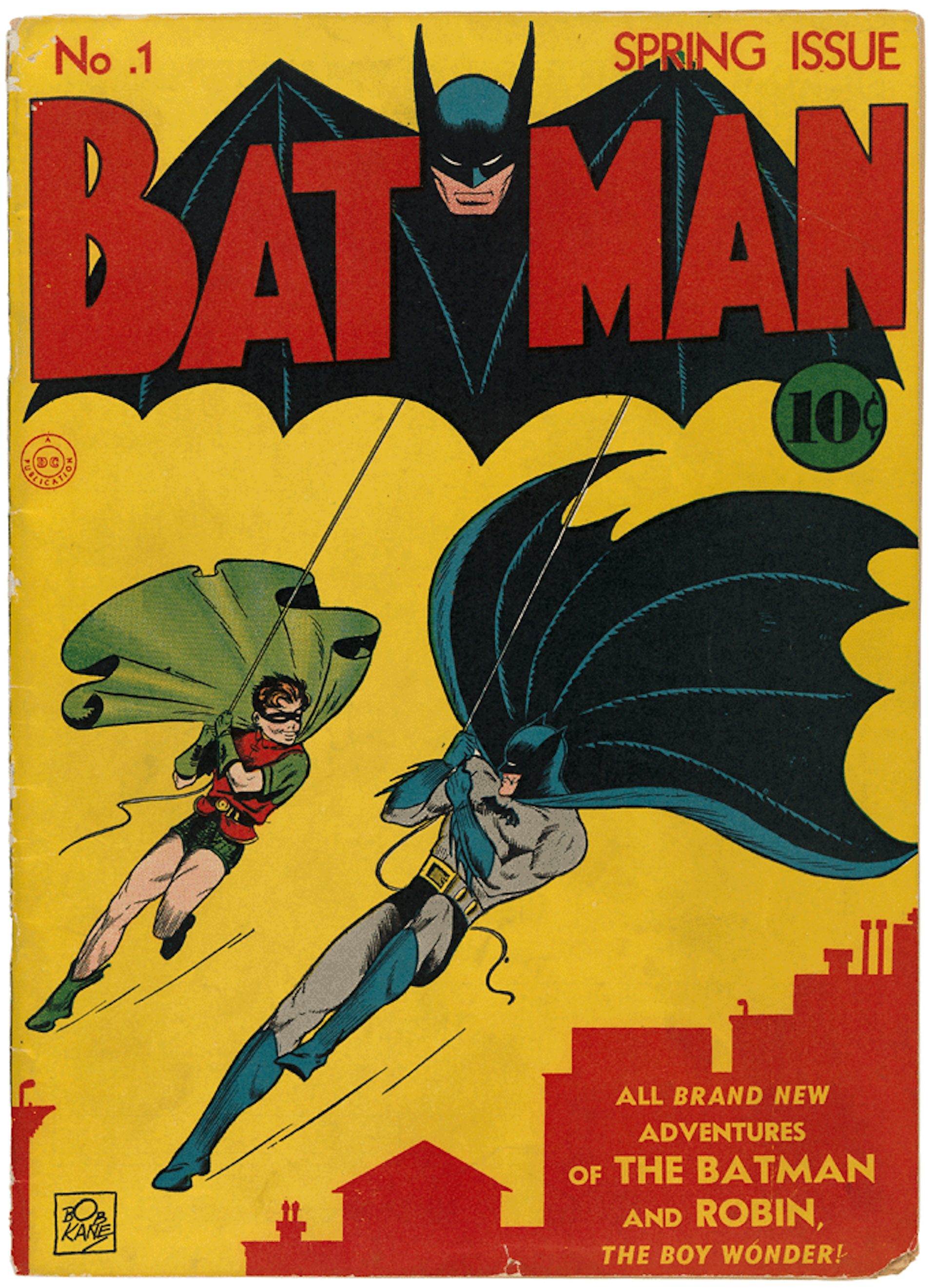

Today, the superhuman heroes of ancient mythology have been transformed into the superheroes of the comic book industry. Popular superheroes such as Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America combine the larger-than-life abilities associated with the heroes of antiquity with the more modern idea of the hero as a moral exemplar.

Batman No. 1 by Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson (March 1940)

National Archives and Records AdministrationPublic DomainDespite these transformations, the Greek heroes also live on in today’s popular culture. Literature, cinema, and the visual arts frequently adapt the myths of Heracles, Achilles, and Perseus, among others.