Ceres

Attic red-figure cup by the Aberdeen Painter (ca. 470–460 BCE) showing Demeter (right) with Triptolemus (left)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainOverview

Ceres was the Roman goddess of grain and fertility (especially agricultural fertility), though she was also associated with women and motherhood, the realm of the dead, law and order, and the protection of the Roman plebeians (the “commoners”).

Most of what we know about Ceres’ mythology, iconography, and worship was modeled on the Greek goddess Demeter. Thus, just as Demeter’s central myth involved her search for her daughter Persephone, who was abducted by Hades, so too is Ceres best remembered for her search for her daughter Proserpina, stolen away by Dis (Hades’ Roman equivalent).

The center of Ceres’ cult was her temple on the Aventine Hill in Rome, where the goddess was worshipped as part of a divine triad alongside the gods Libera and Liber.

In this marble statue from the second century BCE, Ceres the "Munificent" wears a floor-length chiton, a common garment among mature women. In her right hand, she grasps several stalks of harvested grain; in her left she holds a staff. On permanent display in the Vatican Museums, Rome.

Gary ToddPublic DomainWho was Ceres’ Greek equivalent?

Ceres was identified with the Greek goddess Demeter, the Olympian goddess of agriculture. Nearly all of Ceres’ mythology and iconography—and even much of her worship—was based on that of Demeter.

Attic red-figure cup by the Aberdeen Painter (ca. 470–460 BCE) showing Demeter (right) with Triptolemus (left)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainHow was Ceres worshipped?

Ceres was the foremost deity of the so-called “Aventine Triad,” consisting of her, Libera, and Liber. The triad took its name from their temple on the Aventine Hill, dedicated early in Rome’s history.

This Aventine cult was closely affiliated with the plebeians of Rome and symbolized their political equality with the patricians. Indeed, many of Ceres’ festivals, celebrated throughout the year, were connected with the plebeians.

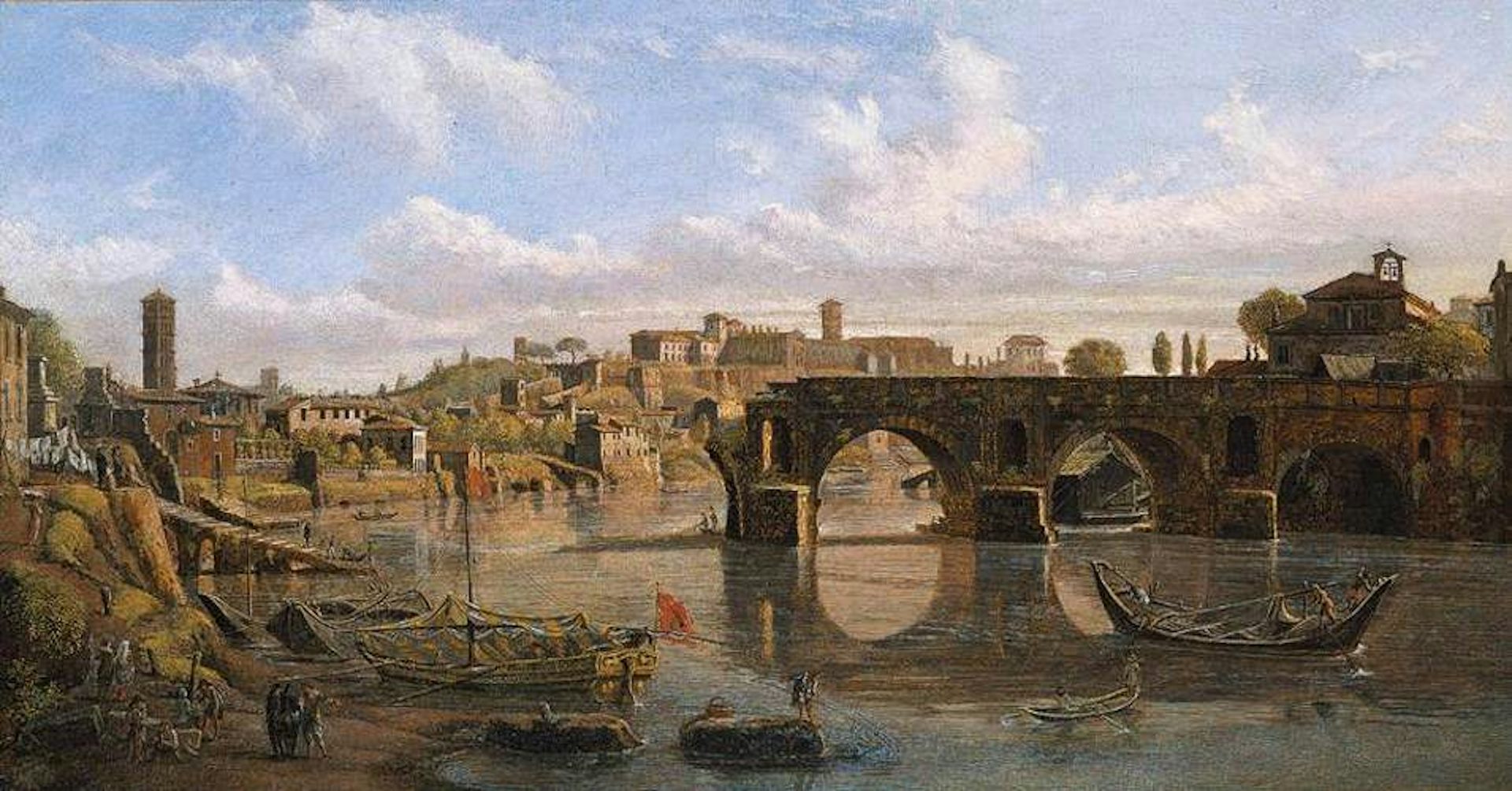

Rome: View of the River Tiber with the Ponte Rotto and the Aventine Hill by Gaspar van Wittel (1680s)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainCeres and Proserpina

Much like the Greek Demeter, a central part of Ceres’ mythos involved the abduction of her daughter Proserpina (Persephone to the Greeks) by the Underworld god Dis (Hades or Pluto to the Greeks). Many Roman authors, including Ovid and Claudian, adapted older Greek traditions to tell of how Ceres searched far and wide for Proserpina after her disappearance.

Though Ceres eventually learned of her daughter’s fate, she was unable to fully rescue her. In the end, Proserpina was allowed to spend part of the year with her mother, but she had to spend the rest of the year in the Underworld with her husband Dis.

Pluto Carrying off Proserpine by William Etty (19th century)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainRoles and Powers

The Romans themselves regarded Ceres as a foreign goddess, adapted from the Greek goddess Demeter. Following the Greek model of the Twelve Olympians, Ceres was counted from early on as one of the “Twelve Gods” of Rome—the most important deities of the Roman pantheon.[1]

Ceres, like Demeter, was first and foremost a goddess of grain and agriculture. Her association with farming and the land—and her role in ensuring fertility and bountiful harvests—was evident from her close connection with Tellus or Terra, the Roman embodiment of the earth. As the poet Ovid wrote in his Fasti,

Ceres and Earth discharge a common function: the one lends to the corn its vital force, the other lends it room.[2]

Ceres Sows Seeds and Walks behind a Goat-Drawn Plough, etching by Pierre Brebiette, published by François Langlois (ca. 1617–1625)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBecause she presided over agrarian life, Ceres was immensely important and powerful in Rome—a city that (like most Mediterranean locales) depended on the success of annual harvests. One law, for example, prescribed that anyone who damaged another’s seeds had to forfeit themselves to Ceres and be hanged.[3]

During the period of the Late Republic and the rise of the Empire, Ceres became increasingly connected with the annona, the public grain supply of ancient Rome.

Ceres had other functions, too. She was a goddess of women and motherhood, protecting the marriage bond between wife and husband. She was also closely connected with the realm of the dead.

Another important function of Ceres was as a goddess of law and order. According to one tradition, recorded by the commentator Servius, human beings originally existed in a lawless and savage state. This condition only ended when Ceres introduced grain and taught humans how to fairly apportion the land for agricultural purposes.[4]

An extension of Ceres’ function as a lawgiver was her role as protector of the plebeians, the Roman class of “commoners.” Throughout the Republic, Ceres represented the fight for political equality between the plebeians and the more aristocratic patricians. Indeed, anyone who harmed the Tribune of the Plebs—an elected magistrate who represented the interests of the plebeians and who was considered sacrosanct—forfeited their life to Ceres.

Attributes

In literature and art, Ceres’ most recognizable attributes were adapted from those of the Greek Demeter. She was perhaps most readily distinguished by the corona spicea, a crown or wreath made of ears of corn or wheat, which encircled her blonde, grain-colored hair.[5]

Ceres’ attributes also included sheafs or ears of grain plants, such as wheat, corn, or poppy, as well as the cornucopia (the “horn of plenty”).

Summer (Ceres) by the Doccia Porcelain Manufactory after a model by Balthasar Permoser (ca. 1760–1770)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainCeres often carried a torch, or even multiple torches; the poet Ovid, for example, described Ceres with a lighted torch in each hand as she searched for her kidnapped daughter Proserpina.[6]

Iconography

In her iconography (as in all of her mythology), Ceres was all but indistinguishable from her Greek counterpart Demeter. Indeed, some of the earliest visual representations of Ceres—namely, the images of the goddess installed in her temple on the Aventine—were produced by Greek artists.[7]

Iconographic representations of Ceres showed the goddess either standing or seated upon the kiste, the chest that housed her sacred objects. She was usually modestly robed and crowned with the corona spicea; often she carried attributes relating to her agricultural function, such as ears of corn, wheat, poppy, or, occasionally, grapevines. She was sometimes accompanied by one of her sacred animals, such as the sow, thus highlighting her sacrificial function.

In some representations, Ceres was accompanied by other gods with whom she was associated, including Apollo, Diana, and Annona (the latter being the personification of the Roman public grain supply).

From the beginning of the Imperial period, Ceres was commonly affiliated with the empress of Rome, who would appropriate the image and attributes of the goddess so as to present herself as a benefactress and protectress of the Roman people (Livia, the wife of Augustus, initiated this trend).

Statue of the Roman Empress Livia as Ceres (between 15 and 20 CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Madrid / Luis GarcíaCC BY-SA 3.0In addition to sculpture, Ceres was often depicted on Roman coins, gemstones, and cameos. In the second and third centuries CE, the abduction of Proserpina became an especially popular scene on stone sarcophagi, with Ceres often shown in the background, torches in hand.[8]

Etymology

The name “Ceres” has been traced back to the Indo-European root *ker, meaning “to grow” or “to nourish.” The goddess’s name is thus related to the Latin verbs crescere (“to grow, arise”) and creare (“to create”), in keeping with her agricultural functions.[9]

From a very early period, Ceres’ name was used as a synonym or metonym for bread, or for food in general.[10] This eventually yielded the modern English word “cereal” (as well as similar words in other European and Romance languages).

Pronunciation

English

Latin

Ceres Ceres Phonetic

IPA

[SEER-eez] /ˈsɪər iz/

Titles and Epithets

A handful of titles and epithets of Ceres are attested from ancient sources, usually tied to the goddess’s various functions. Unsurprisingly, most of these epithets stress her role as a goddess of agricultural fertility. Key examples include frugifera, “crop-bearing”; fecunda or fertilis, “fertile”; genetrix frugum, “creator of the crops”; larga, “abundant”; and potens frugum, “mistress of the crops.”

But Ceres also had epithets related to her other domains. For example, the epithet legifera, “law-bearing,” reflected her role as a goddess of law and order.[11]

Other epithets referred to specific attributes of the goddess. Ovid, for example, addressed Ceres in one of his poems as taedifera, “torch-bearing,” due to the fact that she was often shown wielding torches.[12] Another Roman poet, Manilius, spoke of Ceres spicifera—“bearing the spicea”—after the so-called corona spicea, or crown of corn, that Ceres often wore in ancient art.[13]

Italian bronze medal of Ceres (late 15th–early 16th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainSome of Ceres’ titles seem to have been based on equivalent titles belonging to the Greek Demeter: Ceres Frugifera, for example, corresponds to Demeter Karpophoros; Ceres Legifera to Demeter Thesmophoros; and so on.

Family

Ceres’ genealogy, like the rest of her mythology, was based on that of the Greek goddess Demeter (information on the native Italian genealogy of Ceres, if it ever existed, no longer survives.) She was thus understood as the daughter of Saturn and Ops, the Roman equivalents of the Greek Cronus and Rhea.

Ceres’ brothers included Jupiter, Neptune, and Dis (the equivalents of the Greek Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades, respectively); her sisters were Vesta and Juno (Hestia and Hera).

This 19th century etching of Ceres and Proserpina surrounds the goddesses with symbols of agriculture. Wearing a crown of corn upon her head, Ceres carries a cornucopia in one hand and a sickle in the other.

RijksmuseumPublic DomainWhile Ceres was not known as a particularly amorous goddess, she did give birth to Proserpina, a fertility goddess associated with spring and the Underworld (just as the Greek Demeter was the mother of Persephone). The father in this case was Ceres’ brother Jupiter (following the tradition in which Zeus was the father of Persephone).

The Proserpina of Roman mythology was usually thought to have replaced (or been combined with) the goddess Libera, who was worshipped alongside Ceres in Roman cult; both goddesses were considered daughters of Ceres. Likewise, Libera’s male counterpart, Liber—the third deity of the Aventine Triad—was named as Ceres’ son.[14]

Mythology

Origins

The ancient Romans never contested the fact that Ceres originated from the Greek goddess Demeter. But Ceres may have existed as a native Italian goddess even before the Romans imported the cult of Demeter from Greece.

There are inscriptions, for example, that attest to the existence of a cult of Ceres in central and southern Italy from as early as the late seventh century BCE. In a similar vein, the existence of a special priest of Ceres—the flamen Cerialis—proves that the worship of Ceres in Rome dates back to an early period.[15]

Ceres Begging for Jupiter's Thunderbolt after the Kidnapping of Her Daughter Proserpine by Antoine-François Callet (1777). In this scene, Ceres asks Jupiter to free her daughter Prosperina from the clutches of Pluto, who has stolen away with her to the Underworld.

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainFurther evidence suggesting the early origins of Ceres comes from the Carmen Saliare, one of our most important sources on early Roman religion, where Ceres appears to have been invoked in the form of Cerus manus.[16] Ceres was also included in the long list of deities invoked at the Feriae sementivae, which may have originated in an early native Italian tradition (though it may have been introduced later by members of the Roman priesthood).[17]

The Abduction of Proserpina

If Ceres ever possessed a native Roman mythology, we no longer know anything about it. The Romans, in identifying Ceres completely with the Greek goddess Demeter, also adopted the Greek narratives surrounding Demeter.

Thus, the mythology of Ceres—like that of Demeter—was centered on the abduction of her daughter Proserpina (Persephone in Greek sources) by the powerful chthonic deity Dis (Hades or Pluto). It was one of the most famous myths in the ancient world, first appearing in the second Homeric Hymn and later retold in various Roman sources, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Fasti and Claudian’s Rape of Proserpina.

Proserpina by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874)

Tate Britain, LondonPublic DomainAccording to the conventional version of the myth, Dis fell in love with Ceres’ daughter Proserpina and carried her off to the Underworld to be his bride (in Ovid’s retelling, it was the love gods Venus and Cupid who first sparked Dis’ lust).

Devastated by the loss of her daughter, and not knowing what really happened, Ceres set off in search of the missing girl. Though she traveled far and wide, carrying a torch to help her see clearly, her search was fruitless.

At long last, Ceres made her way to Sicily and found Prosperina’s belt, which had come loose as she was dragged away. In her sorrowful anger, Ceres put a curse on the earth, blighting the crops and leaving the land barren:

Ceres the token by her grief confest,

And tore her golden hair, and beat her breast.

She knows not on what land her curse shou’d fall,

But, as ingrate, alike upbraids them all,

Unworthy of her gifts.[18]

Watching from on high, the other gods and goddesses realized that Ceres’ grief had to be assuaged. Seizing the moment, Jupiter sent Mercury to deliver a message to Dis: the lord of the Underworld was to release Proserpina immediately and return her safely to her mother.

Though Dis consented to Jupiter’s demands, he stated that he would only return Proserpina if she had not consumed any food in the Underworld. Because Proserpina had eaten seven pomegranate seeds from Dis’ subterranean garden, he refused to release the girl.

After much debate, a compromise was reached whereby Proserpina would divide her time between her mother and her abductor. The precise amount of time spent with each was presented differently in different traditions—in early sources, Proserpina spent two-thirds of the year with her mother and the remaining third with her husband Dis, while later sources often had her split the year evenly between her two homes.[19]

Other Myths

In addition to the central myth involving the abduction and (partial) recovery of her daughter, Demeter featured in a handful of other Greek myths, some of which were adapted by Roman sources. One notable example is the myth of Erysichthon, in which Demeter (Ceres) played a sinister part.

In Ovid’s retelling of the myth, Erysichthon was a wealthy but impious king who attacked a sacred grove with his ax. He did not stop even when the trees gushed blood, or when one of the tree nymphs used her dying words to warn him of the sin he was committing.

Erysichthon Selling his Daughter by Jan Steen (1650–1660)

RijksmuseumPublic DomainThe other woodland nymphs appealed to Ceres, who was enraged at Erysichthon’s behavior. To punish him, she sent Fames—“Hunger” or “Famine” personified—to plague him with unending hunger:

’Twas night, when entring Erisichthon’s room,

Dissolv’d in sleep, and thoughtless of his doom,

She clasp’d his limbs, by impious labour tir’d,

With battish wings, but her whole self inspir’d;

Breath’d on his throat and chest a tainting blast,

And in his veins infus’d an endless fast.[20]

Erysichthon quickly exhausted his considerable resources trying to sate his insatiable hunger. Eventually, he sold his daughter Mestra to buy more food. Mestra, however, had the power to change her shape (a gift bestowed upon her by her old lover, the sea god Neptune), and she used this power to escape from her new master and return to her father.

Erysichthon took advantage of his daughter’s ability, selling her again and again to buy more food; every time Erysichthon sold her, Mestra would find a way to change her shape and dutifully return to her father. At last, however, Erysichthon sold Mestra to a handsome young man; Mestra fell in love with this man and forgot her father.

Abandoned by Mestra, Erysichthon soon started to waste away. Eventually, he began to devour himself until nothing was left of him but a pair of lips, forever gnawing and snapping at the air.[21]

For further myths of Demeter/Ceres, see the article on the Greek goddess Demeter.

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

The main temple of Ceres in Rome was the temple on the Aventine Hill dedicated to Ceres, Libera, and Liber (known collectively as the Aventine Triad). The temple was located outside of the Pomerium, the sacred boundary of Rome, not far from the Circus Maximus. It had special significance to the plebeians of Rome.

The Romans seemed to believe that the triad of the Aventine temple mirrored the triad of Demeter, Kore, and Iacchus, Greek deities who were worshipped at the Eleusinian Mysteries. Modern scholars, however, are more hesitant to accept this identification.

Photo of the Telesterion at Eleusis, Greece

Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0Roman tradition connected the Aventine temple to the early years of the Republic. According to Roman records, A. Postumius vowed to build the structure in 496 BCE (following the guidance of the oracular Sybilline Books), and construction was completed by Sp. Cassius in 493 BCE.[24] The temple certainly seems to have been very old, and its archaic style was retained even in later periods.[25]

As a center of plebeian religious life, the Aventine temple was supervised by plebeian magistrates and housed records of senatorial edicts.[26] Assets that were legally seized by plebeian officials as penalty for certain offenses were stored in the temple, too.[27]

The priestesses who oversaw the Aventine temple were Greek, being brought in by the Romans from either Naples or Elea, two of the most important Greek cities of southern Italy. These priestesses were required to remain celibate for the course of their tenure and were eventually awarded Roman citizenship for their services.[28]

Though the cult of Ceres was always centered on the Aventine temple, the goddess did acquire additional temples and sanctuaries throughout the Roman world. In 7 BCE, for example, an altar to Ceres and Ops Augusta (“Sacred Abundance”) was dedicated by the emperor Augustus on the Vicus Iugarius in east-central Rome.[29]

Festivals and Rituals

The Romans thought of Ceres as a Greek goddess. Because of this, the rituals associated with her worship were part of the sacra peregrina, or “foreign rites.”[30]

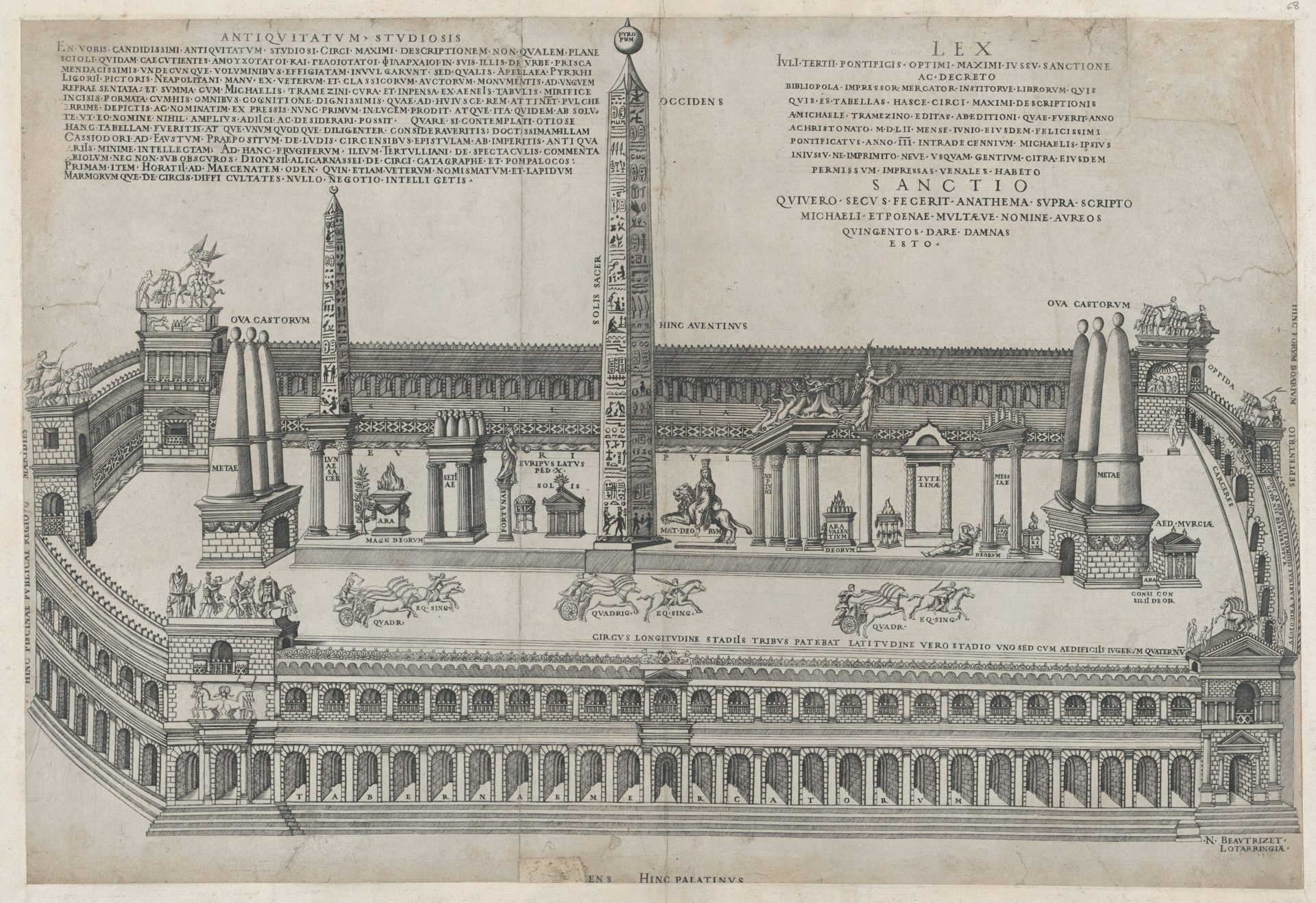

The main festival of Ceres was the ludi Ceriales (“games of Ceres”), celebrated between April 12 and 19 each year, when the crops were budding with new life. A predominantly plebeian affair, the festival featured games such as horse races in the Circus Maximus (the great Roman race track that ended beneath Ceres’ Aventine temple). On the final day—the feast day known as the Cerealia—foxes were let loose in the Circus Maximus with burning torches tied to their tails.[31]

Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: Circus Maximus, engraving by Nicolas Beatrizet after Pirro Ligorio, published by Michele Tramezzino (1553)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAnother festival of Ceres was the Feriae sementivae, celebrated in January during a break in the sowing season. This festival featured sacrifices, including the sacrifice of a pregnant sow to both Ceres and Tellus.[32]

Yet another festival, the Sacrum anniversarium Cereris, was celebrated in August of each year. This festival was restricted to women, much like the Greek festival Thesmophoria from which it may have originated. It was marked by the wearing of white clothing as well as a number of prohibitions, including prohibitions on wine and sex and a taboo involving names.[33]

Ceres was connected with many other festivals, too, especially those celebrated in April (due to the month’s agricultural importance). These included the Fordicidia (April 13), the Parilia (April 19), the Vinalia (April 23), and the Robigalia (April 25).

The Ieiunium Cereris (celebrated on September 4) was introduced in 191 BCE at the prompting of the Sibylline Books,[34] and every December 21 an offering of a pregnant sow, bread, and mead was made to Ceres and Hercules.[35]

One special rite, the Mundus Cereris, was held three times a year and was associated with Ceres in her capacity as an Underworld goddess. Offerings were made to both Ceres and the Underworld deities Dis, Proserpina, and the Manes.[36]

Other rituals connected with Ceres were less regular. In times of public crisis, for example, women would perform supplicatory walks in honor of Ceres and her daughter, gathering gifts that they would then present to the goddesses.[37]

As an object of private cult, Ceres received sacrifices from landowners and farmers before the beginning of the harvest, as well as offerings of first fruits.[38] As a goddess of marriage, Ceres was represented in the wedding torch that was lit at Roman weddings.[39] Moreover, a man who illegally divorced his wife was required to forfeit his assets to Ceres. [40]

Finally, as a goddess of death, Ceres received a sacrifice of a sow from anyone who had been in contact with a person who had died; this was considered a way to regain ritual purity.[41]

Popular Culture

Though Ceres is seldom represented in traditional pop culture, she still regularly appears as a symbol of agricultural fertility. For example, a statue of Ceres sits atop the Chicago Board of Trade Building, which hosts several agricultural offices. Similar statues rest atop the Missouri State Capitol building in Jefferson City and the Vermont State House in Montpelier. In these latter cases, Ceres is depicted wearing robes and clutching a bundle of grain.

A statue of Ceres adorning the dome of the Missouri State Building in Jefferson City, Missouri. This interpretation of the goddess wears a laurel wreath and carries a bundle of grain beneath her arm. Intended to represent one of the state's staple industries, the statue was installed in 1924.

MIssouri State Capitol CommissionPublic DomainCeres has also lent her name to a celestial body: the dwarf planet Ceres was discovered in 1801 by Father Guiseppe Piazza and is located within the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. She also gave her name to the element cerium, discovered in 1803.

Perhaps more familiar today, Ceres’ name also forms the basis of the word “cereal,” referring both to grain crops and to the breakfast foods made from them.