Juno

Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix showing Hera (left) and Prometheus (right) by Douris (ca. 490–480 BCE), from Vulci

Cabinet des médailles, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainOverview

Juno (or Iuno in Latin) was the queen of the Roman gods and the wife of Jupiter, the king of the gods. She served as a champion and protector of women, especially in their domestic roles of marriage and motherhood. Juno’s mythology and iconography were mostly adopted from the Greek goddess Hera.

Juno was one of the most important gods of the Roman state. She had important sanctuaries on the Aventine Hill in Rome, as well as the Capitoline Hill, where she was worshipped alongside Jupiter and Minerva at the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

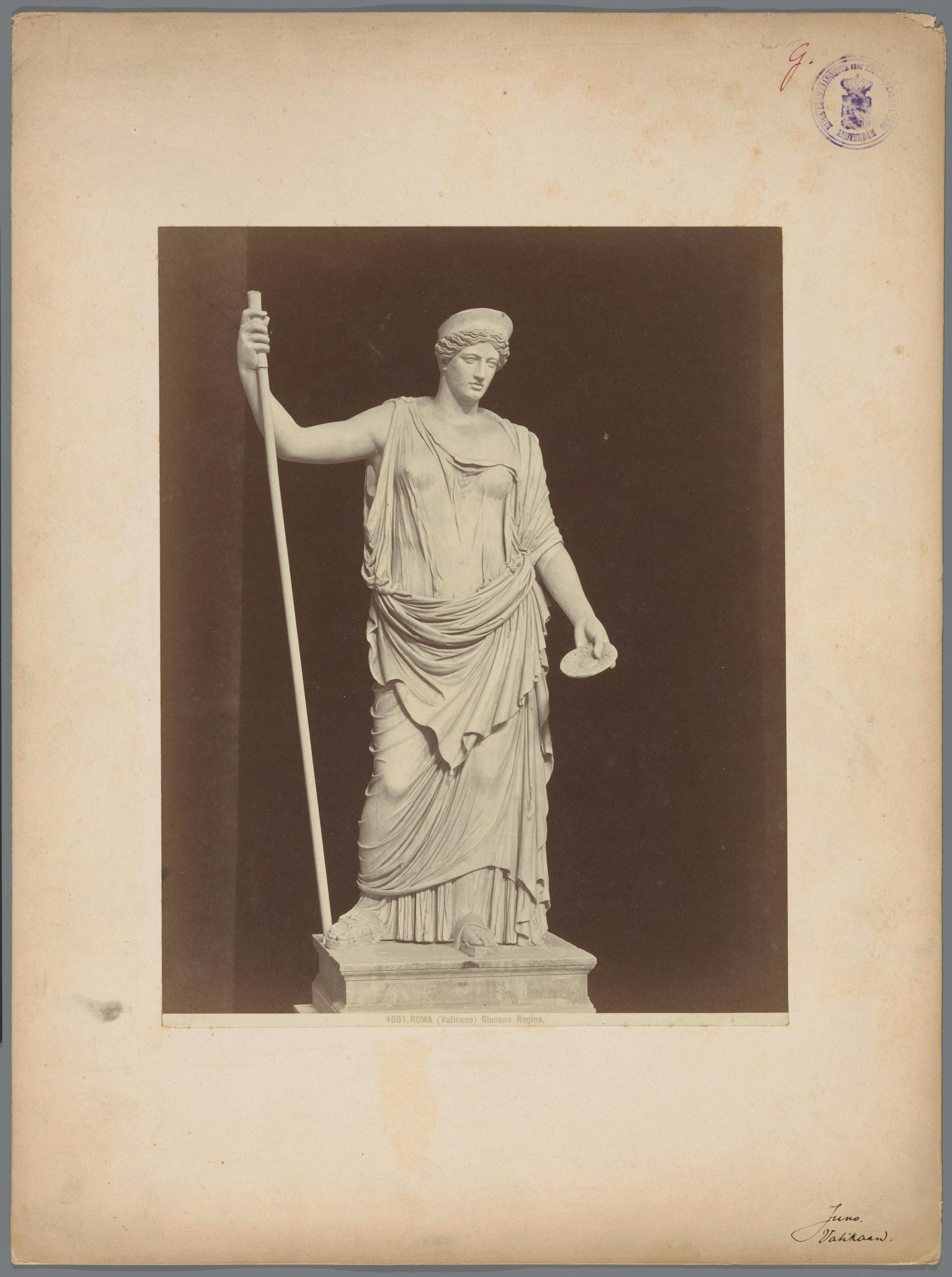

As queen of the Roman deities, Juno was often depicted wearing some sort of crown. In this marble sculpture, she wears a diadem.

Museum of Fine Arts, BostonPublic DomainKey Facts Who was Juno’s Greek equivalent?

Juno was generally identified with the Greek goddess Hera. Like Hera, Juno was the queen of the gods and the protector of women and the family. Much of Juno’s mythology and iconography was based on Hera’s.

Juno, however, was more of a civic goddess than Hera, worshipped as one of the patron gods of the Roman Empire. She had a large number of titles demarcating her diverse roles in Roman worship.

Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix showing Hera (left) and Prometheus (right) by Douris (ca. 490–480 BCE), from Vulci

Cabinet des médailles, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainWhat were Juno’s attributes?

Juno was represented very similarly to the Greek Hera: she was a regal figure, typically shown in a chiton (tunic) and cloak, which she sometimes used to veil her head. She was usually depicted wearing a crown and holding a scepter or patera (a libation bowl).

Like Hera, Juno’s favorite animal was the peacock. In ancient art, peacocks were frequently depicted alongside the goddess.

Juno and the Peacock, bronze statue after a model by Alessandro Vittoria (16th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainJuno and Aeneas

In Virgil’s epic poem the Aeneid, Juno is depicted as the divine antagonist of Aeneas, the Trojan hero who came to Italy and became the ancestor of the Romans. Virgil’s Juno hates Aeneas because she hates all Trojans, but also because she is the patron goddess of Carthage, a city that would eventually be destroyed by Aeneas’ Roman descendants.

Juno hounds Aeneas relentlessly throughout the Aeneid. She buffets him with storms, turns the Latins against him when he reaches Italy, and maneuvers the conflict between Aeneas and the Italian hero Turnus. In the end, however, Juno must make peace with the fact that it is Aeneas’ destiny to prevail and put into motion the events that will lead to the rise of Rome.

Dido's Sacrifice to Juno by Jean Bernard Restout (ca. 1772–1774)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainRoles and Powers

Juno had two main roles or domains in the Roman world: one involved women and everything connected to women’s lives and livelihoods, while the other was the state and its young male warriors.

Juno was especially associated with married women, though she was considered the guardian of all women. Over time, the Romans even began to use juno as a term for the tutelary deity that accompanied every woman from birth to death. (The male equivalent was called the genius.)

Juno was invoked in connection with all aspects of female life. As Juno Lucina, for example, she was a goddess of childbirth. As Juno Iugalis (or Juno Iuga), she was a goddess of marriage and wedding rituals. More specifically, as Juno Cinxia, “Juno of the Girdle,” she presided over the loosening of the girdle on a woman’s wedding night.[1]

Juno was also a goddess of the state and of adolescent male soldiers. Much of the evidence for this role comes from central Italy. At Lanuvium, Juno was worshipped as Juno Sospita (also attested as Sispes or Sispita),[2] the protectress of warriors. This Juno had a particularly distinctive appearance, wearing a horned goatskin and pointed shoes and carrying a spear and shield.[3]

Statue of Juno Sospita (2nd century)

Vatican Museums / DarafshCC BY-SA 3.0Juno served similar protective functions as Juno Quiritis (or Curitis) in Falerii;[4] Juno Argeia in Tibur;[5] and Juno Populona in Aesernia[6] and Teanum Sidicinum.[7]

Juno Regina, “Queen Juno,” was also a highly important state goddess connected with the military. Though she was initially the principal goddess of Veii, Ardea, and Lanuvium, the worship of Juno Regina was said to have been transferred to Rome in 392 BCE, after Furius Camillus conquered Veii.[8]

Finally, a uniquely Roman form of civic Juno was Juno Moneta, usually translated as “Juno the Warner” or “Juno Who Warns.”[9] Juno Moneta was connected with the state and its warriors as well as with the mint.

Attributes

Juno’s attributes were heavily influenced by those of her Greek counterpart, Hera. Juno, like Hera, was imagined as the archetypal queen; she usually wore a crown and sometimes held a scepter or a type of libation bowl called a patera. Her favorite animal was the peacock, which frequently accompanied her in literature and art.

Iconography

Of all the Junos, the iconography of Juno Regina is the best attested. Her statue would have stood in the left cella (inner chamber) of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Though this statue is now lost, it was often illustrated in antiquity, especially on coins.

Statue of Juno Regina, photo taken between 1850 and 1900

RijksmuseumCC0As Juno Regina, Juno was shown either standing or enthroned, wearing a tunic (called a chiton), a cloak, and a crown (called a stephane). In her hands she held a scepter and/or a patera, and there was usually a peacock at her side.

But some representations of Juno were very different. As Juno Sospita, the goddess was decked out for war, with goatskin, spear, and an octagonal shield; she wore pointed shoes and often had a snake at her feet (see above). As Juno Regina Dolichena—the consort of the Jupiter Dolichenus worshipped in Syria—the goddess was shown standing on the back of a hind or cow and holding a mirror.[10]

Etymology

The name “Juno” (Latin Iuno) is usually thought to be derived from various terms related to youth and youthfulness, including the Latin words iunior (“adolescent”) and iuventas (“youth”). The name probably came from the Indo-European root *h₂ieuh₃on-, also meaning “adolescent” or “youth.”

Pronunciation

English

Latin

Juno Iuno Phonetic

IPA

[JOO-noh] /ˈdʒu noʊ/

Alternate Names

In the ancient world, Juno was seen as a counterpart to the Etruscan goddess Uni, the chief deity of the Etruscan people. The Etruscans were an early Italian people whose culture greatly influenced the Romans. Many scholars have speculated that the name “Uni” is etymologically connected to the name “Juno,” though it is unclear which name influenced the other.

Juno’s Greek equivalent was the goddess Hera. The Romans tended to view these goddesses as interchangeable, adopting much of Hera’s mythology and iconography for their Juno.

Titles and Epithets

Juno bore many titles and epithets, reflecting her diverse roles and functions in Roman culture. As goddess of the state and consort of the high god Jupiter, she was called Juno Regina, “Queen Juno.” As protector of the city and its warriors, she was called Juno Sospita, “Juno the Savior,” Juno Moneta, “Juno the Warner,” or Juno Curitis, “Juno of Curia.”

As a goddess of childbirth, she was called Juno Lucina, “Juno Who Brings to Light”[11] (referring to the fact that she brought newborn children into the light).

Juno Sospita, or “Juno the Savior,” depicted on the obverse (left) of a denarius, c. 105 BCE.

Art Institute of ChicagoPublic DomainThese were some of Juno’s most important cult titles, though she had others, too (some of them more literary than cultic). Juno Iugalis (or Iugala) was the goddess of marriage, while Juno Cinxia was “Juno of the Girdle” (referring to the loosening of the girdle on a woman’s wedding night).

As Juno Fluona, the goddess was connected with sexuality, while Juno Covella was linked to the new moon (luna cava in Latin).

Family

Juno’s mythical genealogy was based on that of her Greek counterpart, Hera. Thus, Juno’s parents were the gods Saturn and Ops, the Roman equivalents of the Greek Titans Cronus and Rhea. Juno’s siblings were Jupiter (Zeus), Neptune (Poseidon), Ceres (Demeter), Vesta (Hestia), and Pluto (Hades).

Family Tree

Mythology

Origins

Little is known about the original nature and function of Juno (prior to the influence of the Greek Hera). The cult of Juno was extremely important in central Italy, and many scholars today speculate that it was from central Italy that the Romans first imported the goddess.

It is possible that Juno was originally a goddess of the Sabines, a people who lived just south of Rome. Indeed, Roman sources record that the earliest Roman altars and dedications to Juno were set up by the Sabine king Titus Tatius.[12] Likewise, the earliest Roman temple to the Capitoline triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva stood on the Quirinal Hill, a hill associated with the Sabines.[13]

If Juno was a Sabine or central Italian goddess, then her cult must have traveled north to Rome (and ultimately to Etruria) at an early date—by the seventh century BCE.

Today, this explanation of Juno’s origins is regarded as more likely than the alternative view—namely, that Juno originated in northern Italy with the Etruscan goddess Uni (linguistically, the Etruscan name “Uni” looks like a derivation of the Latin “Iuno,” rather than vice versa).

Juno and Other Deities (c. 1700). Juno assumes command of the scene from atop her golden chariot. The nearby peacocks may symbolize her beauty or royal status.

Yale University Art GalleryPublic DomainJuno and the Romans

In Roman mythology, Juno is largely identical with the Greek Hera. Indeed, the Romans made a habit of borrowing and appropriating the mythology of the Greeks, substituting Roman names for the original Greek ones.

However, some of the myths and legends that the Romans told about Juno were more unique to Roman culture. For example, Juno played a key role in several myths about the rise of Rome (usually opposing the empire rather than supporting it).

Juno and Aeneas

In Virgil’s epic poem the Aeneid, Juno is presented as the chief divine adversary of Aeneas, the Trojan hero who sailed to Italy and became the ancestor of the Romans. When Troy fell to the Greeks in the Trojan War, Aeneas fled the burning city with his father Anchises, his son Ascanius, and a band of refugees. Together they sailed west to Italy, spurred on by a prophecy that Aeneas’ descendants would one day rule the world.

But Aeneas’ descendants—the Romans—were also destined to conquer Carthage, a city very dear to Juno, thus earning the goddess’s wrath. Juno also hated the Trojans because the Trojan prince Paris had determined that Venus (Aphrodite) was lovelier than her in the so-called “Judgment of Paris.”

In this medieval French work recounting a scene from Virgil’s Aeneid, Juno summons a Fury to enact her revenge.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainMoved by her “unrelenting hate,”[14] Juno did everything she could to destroy Aeneas and his Trojan followers, or at least make their journey as difficult as possible. She sent a storm to wreck Aeneas’ fleet on the coast of Africa, near the site where Dido was building the new city of Carthage.

While Aeneas was waylaid in Carthage, Juno plotted to make him and Dido fall in love, hoping that this would stop him from sailing to Italy. Though Juno succeeded in uniting them as lovers, Aeneas still left in the end (Dido, in despair, committed suicide as she watched him go).[15]

Soon Aeneas reached Italy, even as Juno continued to forestall his voyage.[16] Landing in the region of Latium, the Trojans sought to establish friendly relations with the local king Latinus. Aeneas even made arrangements to marry Latinus’ daughter Lavinia.

But Juno would not let her enemy off so easily. She sent Alecto, one of the Furies, to inspire a desire for war in Latinus’ wife Amata, Lavinia’s suitor Turnus, and the local Latins.[17] Over the course of the bitter conflict, Hera continued to support the Latins against Aeneas; she interceded with her husband Jupiter on behalf of Turnus,[18] and later even tried (in vain) to prevent the final showdown between Turnus and Aeneas.[19]

Aeneas and Turnus by Luca Giordano (17th century)

Palazzo Corsini, FlorencePublic DomainIn the end, though, Juno was forced to accept that Aeneas was destined to defeat Turnus and establish his new home in Italy. As a concession, Jupiter agreed to her request that the Trojans not supercede her beloved Latins:

[...] let the Latins still retain their name,

Speak the same language which they spoke before,

Wear the same habits which their grandsires wore.

Call them not Trojans: perish the renown

And name of Troy, with that detested town.

Latium be Latium still; let Alba reign

And Rome’s immortal majesty remain.[20]

Juno and the Wars of the Romans

The Romans told a handful of legends about Juno’s involvement in their early wars. In many of these tales, she functions as an adversary rather than a supporter of the Romans (comparable to her role in the myth of Aeneas).

In one legend, set during the reign of Romulus, Juno tried to help the Sabines in their war against Rome. The Sabines had invaded Rome after Romulus, the first king of Rome, instructed his subjects to abduct the Sabine women and make them their wives (the legend known as the “Rape of the Sabine Women”). The husbands and fathers of the Sabine women amassed an army and attacked Rome in order to retrieve their female relatives.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman by Giambologna (1579–1583)

Loggia dei Lanzi, FlorenceCC BY-SA 2.5It was said that as the Sabines were assaulting the walls of Rome, Juno lent them her aid by removing the bolts of the Porta Ianualis, the “Janus Gate.” The god Janus—to whom the gate was dedicated—noticed this but did not confront Juno directly, as he did not wish to offend the great goddess.

Even so, Janus could not let Rome be overrun; thus, he enlisted the help of the nymphs to create a flood of boiling water. This flood held the Sabines back long enough to allow Romulus to prepare his forces to meet the enemy.[21]

Juno was also sometimes depicted as supporting the Carthaginians in fictionalized or mythicized accounts of the Punic Wars, especially the Second Punic War (fought between 218 and 201 BCE). In Silius Italicus’ Punica, for example—the longest ancient Roman epic—Juno is represented as a staunch supporter of the Carthaginian general Hannibal, using him as an instrument to punish Rome.[22]

In the Punica, Juno stands by Hannibal at his most important battles. She inspires him before the Battle of Lake Trasimene,[23] and later sends Anna Perenna—the deified sister of Hannibal’s ancestor Dido—to calm Hannibal’s anxieties on the eve of the Battle of Cannae.[24]

After Hannibal wins his staggering victory over the Romans at Cannae, Juno again intercedes. She first sends Somnus, the god of sleep, to deter Hannibal from immediately marching on Rome, as doing so would put him in danger.[25]

Later, when Hannibal is about to do battle with the Romans before the walls of Rome, a sudden downpour of rain and hail drives both armies back. The same thing happens the next day—though as soon as the armies withdraw, the weather calms. Juno finally appears to Hannibal again, revealing that the weather is a sign that Rome is under the gods’ protection.[26]

Hannibal Barca Counting the Rings of the Roman Knights after the Battle of Cannae by Sébastien Slodtz (1704)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainHannibal has no choice but to withdraw. Little by little, his good fortune turns until he is defeated by the Roman commander Scipio and forced into exile. By the end of the Punica, Juno must reconcile herself to the inevitable supremacy of Rome.

In another legend, Juno actually supported Rome (albeit indirectly), rather than opposing it. After the Gauls defeated the Romans at the Battle of the Allia (ca. 387 BCE), the Romans shut themselves behind their walls. The Gauls, tired of besieging the city, decided to scale the walls under the cover of night. But the sacred geese kept in the precinct of Juno made such a clamor that a Roman soldier, M. Manlius, woke up and repelled the attackers.[27]

The Gauls did manage to sack Rome soon after, but the story of Juno’s geese was remembered as an important example of her intercession on behalf of the Romans.

Other Myths

There were a handful of other distinctively Roman myths involving Juno. These tended to take up themes from the mythology of the Greek Hera, especially the theme of Hera’s jealousy over her husband Zeus’ many affairs.

One story told of how Juno was jealous when her husband Jupiter (Zeus) gave birth to Minerva (Athena) on his own (Athena’s birth from her father Zeus’ head was a very popular Greek myth). Juno headed out to complain to the Titan Oceanus, an important sea god, stopping at the home of the goddess Flora on the way.

Roman mosaic from Carthage showing Flora

JerzystrzeleckiCC BY 3.0During this visit, Juno asked Flora to help her conceive a child without Jupiter, just as Jupiter had conceived without her. In response, Flora gave Juno a magical flower that made her pregnant. Juno went to Thrace, where she gave birth to Mars, the god of war. Juno was so pleased that she awarded Flora cult honors in Rome.[28]

Juno also played a role in the myth of Lara, a nymph known for her gregarious and talkative nature. One day, Lara said too much while speaking to Juno, betraying Jupiter’s affair with Juturna (the sister of Aeneas’ enemy Turnus). To punish her for revealing his secret, Jupiter cut out her tongue and put her under the charge of his son Mercury, who raped her.[29]

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

Juno had a seat of honor in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill, the most important religious sanctuary in ancient Rome. She was honored there next to her husband Jupiter, the supreme god of the Romans, as Juno Regina, “Queen Juno.”

Of the three cellae (inner chambers) of the temple, the left one was dedicated to Juno, the central one was Jupiter’s, and the right one was Minerva’s. Together, these three gods were known as the Capitoline Triad.

Marble statue of the Capitoline Triad, showing Jupiter (center) flanked by his wife Juno (left) and daughter Minerva (right) (ca. 160–180 CE)

Rodolfo Lanciani Archaeological Museum, Guidonia Montecelio / ManuelarosiCC BY-SA 4.0Juno had many other important temples in Rome, including a sanctuary of Juno Lucina. This sanctuary encompassed both a grove on the Esquiline Hill and a temple consecrated by the matrons of Rome in 375 BCE.[31]

There were various rules and taboos associated with this temple, where Juno was honored as a goddess of childbirth. For example, no one wearing a knot was allowed to enter the sanctuary,[32] and pregnant women had to wear their hair loose when praying.[33] In this way, complications or “knots” in childbirth could be avoided.

Another sanctuary to Juno as a domestic goddess was located in the Vicus Lugarius (an ancient street leading into the Roman Forum). Here she was worshipped as Juno Iuga or Juno Igalis, “She Who Joins in Marriage.”[34]

In her capacity as the goddess of young warriors and the state, Juno had important sanctuaries throughout Rome. The temple of Juno Sospita, for example, was built in 194 BCE by the commander C. Cornelius Cethegus in fulfillment of a vow he had made while warring with the Insubres.[35]

Another temple, this one to Juno Populona, was probably built in recognition of Juno’s role as the goddess who presided over the people (the populus) marching off to war.[36]

The cult of Juno Regina—with which the Juno of the Capitoline Triad would come to be connected—was said to have been brought to Rome through war. Roman historians recorded that Furius Camillus transferred the cult of Juno Regina to Rome after the conquest of Veii in 392 BCE, building a temple for the goddess on the Aventine Hill.[37]

Later, new temples were consecrated for Juno Regina by M. Aemilius Lepidus (in 179 BCE)[38] and Q. Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus (in 146 BCE).[39]

Juno Moneta was a uniquely Roman goddess with a temple on the Arx (“Citadel”) of Rome. This temple was an old one, consecrated in 344 BCE by Furius Camillus,[40] and was connected with the Roman mint.

Obverse of a Roman denarius showing Juno Moneta (46 BCE)

GeniCC BY-SA 4.0Of course, Juno did not belong solely to the Romans; she also had sanctuaries throughout central Italy, where she was widely worshipped. Some of these sanctuaries are known from literary sources, though others failed to make a dent in the literary tradition.

For instance, at Gabii, some 11 miles east of Rome, a large second-century BCE temple complex of Juno was unearthed by archaeologists. This temple, however, does not appear in any surviving ancient texts.

Festivals and Rituals

The Roman people honored Juno with many festivals spread across the calendar year. The Kalends, for instance—the first day of the Roman month—was always consecrated to Juno (just as the Ides, the middle day of the Roman month, was sacred to Jupiter). On this day, the goddess was honored with sacrifices at the Regia in Rome.[41]

Many of the rituals connected with Juno hinged on her role as the goddess of childbirth. Before every birth, a coin was offered to Juno Lucina—a custom attributed to a law established by the legendary Roman king Servius Tullius.[42] After the birth of a child, a table with gifts to Juno Lucina was set up in a private room of the home for a full month.[43]

The Matronalia, a festival celebrated on the first of March,[44] was probably also connected with Juno as the goddess of childbirth and marriage. During this festival, husbands would present gifts to their wives. The festival was said to have been founded by Romulus, the first king of Rome, to commemorate the role the Sabine women played in reconciling the Romans and the Sabines.[45]

Other festivals and rituals were related to Juno’s role as a civic goddess. For example, Juno Curitis or Quiritis received regular sacrifices from the curiae (political and military divisions of Roman citizens), based on a custom attributed to the legendary Sabine king Titus Tatius.[46]

Juno Curitis/Quiritis was worshipped in the Campus Martius, the “Field of Mars,” and in other parts of ancient Latium.[47] In the Latin city of Falerii, the festival of Juno Curitis/Quiritis featured a suovetaurilia—a sacrifice of white female cattle, calves, pigs, and rams. At this same festival, boys armed with spears would hunt a goat in ritual contest.[48]

Some ancient festivals of Juno connected the goddess with the world of agriculture and fertility. The Nonae Capratinae—also known as the Caprotinia, or the Feast of Juno Caprotina—was a celebration of social role reversal held on July 7 in anticipation of the summer grain harvest.[49]

Juno was also one of the gods of the Lupercalia, a pastoral festival celebrated in mid-February. During the Lupercalia, priests known as the Luperci would run through the city “whipping” women with straps made of the skin of a sacrificed goat; these skins, which were supposed to confer fertility on any woman they touched, were sacred to Juno Lucina.[50]

Lupercalia by Andrea Camassei (ca. 1635)

Museo del Prado, MadridPublic DomainForeign Cults

The cult of Juno was heavily influenced by foreign cults, though it would also go on to shape other cults in turn.

The Greek goddess Hera, of course, played a formative role in the development of Juno’s cult in Rome. The two goddesses were routinely identified with each other, and many of the ceremonies associated with the cult of Juno were conducted Graeco ritu—that is, “in the Greek style of ritual.”

In the provinces controlled by the Roman Empire, the cult of Juno did not have as great an impact as that of some of the other gods. But Juno did play a significant role in northern Italy, where local mother goddesses were sometimes known as the Iunones, or the “Junos.”

In northern Africa, Juno Caelestis (“Heavenly Juno”) took the place of the Punic goddess Tanit after the Romans destroyed Carthage in the second century BCE. Meanwhile, Juno Dolichena was the version of Juno who served as the consort of Jupiter Dolichenus, a hybrid deity representing the conflation, or “syncretism,” of the Roman Jupiter and Anatolian sky gods such as the Hittite Teshub.

Temple of Juno Caelestis (“Juno the Heavenly”), near ancient Carthage in Dugga, Tunisia. The Romans conquered Carthage in 146 BCE following a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars.

Dennis jarvisCC BY-SA 2.0Popular Culture

Juno recently lent her name to a space probe launched to investigate the planet Jupiter in 2011. Built by Lockheed Martin and operated by NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Juno is currently orbiting the gas giant, examining its magnetic and gravitational fields and composition.

Juno’s name also appears in the title of the 2007 film Juno, starring Elliot Page and Michael Cera. The movie makes no mention of the Roman goddess specifically, but the story—which centers on the travails of a pregnant teenager—involves themes of youth, motherhood, and child-rearing, all traditional domains of Juno.