Minotaur

The Minotaur by George Frederic Watts (1885).

TatePublic DomainOverview

The Minotaur was a monster with the head of a bull and the body of a man. Pasiphae, the wife of the Cretan king Minos, had fallen in love with the Cretan Bull and devised a way to couple with it; the Minotaur was the result of that union. It was imprisoned in a huge maze called the Labyrinth, where it received regular sacrifices of young men and women. Eventually, the monster was slain by the Athenian hero Theseus, who entered and escaped the Labyrinth with the help of Minos’ daughter Ariadne.

Etymology

In ancient Greek, “Minotaur” is a compound of the name Minos and the word tauros (“bull”). “Minotaur” can thus be translated as “the bull of Minos.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Minotaur Μινώταυρος Phonetic

IPA

[MIN-uh-tawr] /ˈmɪn əˌtɔr/

Alternate Names

In some traditions, the Minotaur’s real name was Asterion.[1] This name, which means “the starry one,” suggests a connection with the constellation Taurus, the bull.

Attributes and Iconography

Locale

The Minotaur was born into the household of Minos, the king of the powerful island of Crete. Minos imprisoned the beast in a maze called the Labyrinth, located near his palace in Knossos, where it fed off of young men and women who were sacrificed as tributes.

Appearance and Iconography

The Minotaur was a fearful hybrid creature; according to the writer Apollodorus, it “had the face of a bull, but the rest of him was human.”[2] In many artistic depictions, the Minotaur also had a bull’s tail and an unusually hairy body.

Ancient sources did not always specify which half of the Minotaur was bull and which half was man. The Roman poet Ovid, for example, described the Minotaur simply as “half ox, half man.”[3]

Presumably, it was considered common knowledge that the creature had a bull’s head and a man’s body: this was how it was always depicted in Greek and Roman visual art.[4]

This led to some confusion in the Middle Ages, however. During this period, Ovid’s poetry was perhaps the most familiar source for the myth, causing many European readers to imagine the creature with the head of a man and the body of a bull—the reverse of the ancient tradition.[5]

Family

Family Tree

Tondo of Attic kylix showing Pasiphae and the Minotaur, by the Settecamini Painter (340-320 BCE).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainParents

Father

Mother

- Pasiphae

Siblings

Sister

Mythology

Origins

The disturbing story of the Minotaur began when Poseidon, the god of the sea, sent a snow-white bull to the Cretan king Minos as a sign of his divine favor. Minos was supposed to sacrifice this bull—the Cretan Bull, as it was usually called—but the king was so taken by its perfection that he decided to add it to his royal herd instead.

Deprived of his sacrifice, Poseidon exacted a cruel revenge. He caused Minos’ wife, Pasiphae, to fall in love with the Cretan Bull. After much agonizing, Pasiphae came up with a way to satisfy her forbidden passion: she had Daedalus, a famous Athenian craftsman and architect, design a completely lifelike hollow wooden cow. She then hid inside. Soon enough, the Cretan Bull came and coupled with the wooden cow, thinking it was real. In this way, Pasiphae was able to consummate her love for the bull. The result of their union was the monstrous Minotaur, who combined the natures of its two parents.[6]

The Labyrinth

The Minotaur rapidly grew into a fearsome, savage creature. Minos, tasked with controlling the beast, eventually decided to imprison it in a huge maze, the Labyrinth, which he had built in Knossos next to his palace. The Labyrinth was designed by the architect Daedalus—the same man who built the wooden cow that Pasiphae used to seduce the Cretan Bull. Ovid vividly describes how Daedalus laid out the Labyrinth:

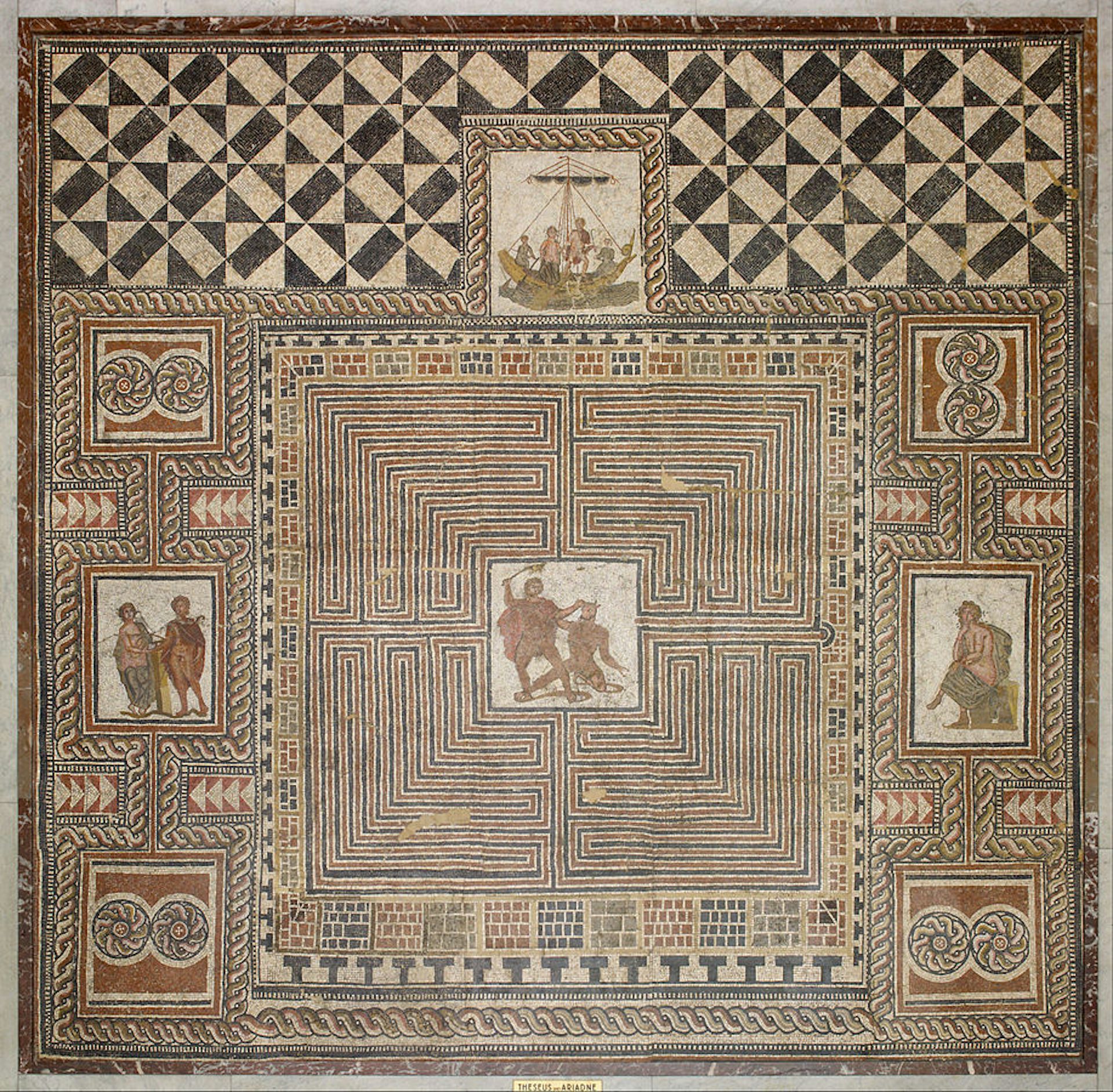

The "Theseus Mosaic" (300–400 CE), discovered in the floor of a Roman villa at the Loigerfelder near Salzburg, Austria. The battle between Theseus and the Minotaur is pictured at the center of an elaborate Labyrinth.

Google Arts and CulturePublic DomainThis he planned

of mazey wanderings that deceived the eyes,

and labyrinthic passages involved.

so sports the clear Maeander, in the fields

of Phrygia winding doubtful; back and forth

it meets itself, until the wandering stream

fatigued, impedes its wearied waters' flow;

from source to sea, from sea to source involved.

So Daedalus contrived innumerous paths,

and windings vague, so intricate that he,

the architect, hardly could retrace his steps.[7]

It was here that the Minotaur was kept, hidden from the civilized world. But Minos could never entirely ignore the creature, and young men and women were regularly sent into the Labyrinth as tributes or sacrifices. The savage Minotaur, who had a taste for human flesh, would devour them once they entered the maze.

Theseus

For a long time, the Minotaur fed on young men and women from Athens. This tradition began with the violent death of Minos’ son Androgeus. Minos blamed the Athenians for Androgeus’ demise (the details of the myth vary by source), and as punishment, he demanded that the Athenians send him a regular tribute of fourteen youths: seven boys and seven girls. These would be thrown into the Labyrinth and consumed by the Minotaur. In most traditions, the Athenians were forced to send this terrible tribute once every nine years,[8] but in some versions of the story they sent it as often as every year.[9]

When Theseus came to Athens after discovering that his father was the Athenian king Aegeus, he vowed to put an end to this violent custom once and for all. According to the common tradition, he volunteered to sail to Crete as one of the tributes. There, he was fortunate enough to catch the eye of Ariadne, Minos’ daughter. Ariadne agreed to help Theseus kill the Minotaur if he would promise to take her with him to Athens and make her his wife.

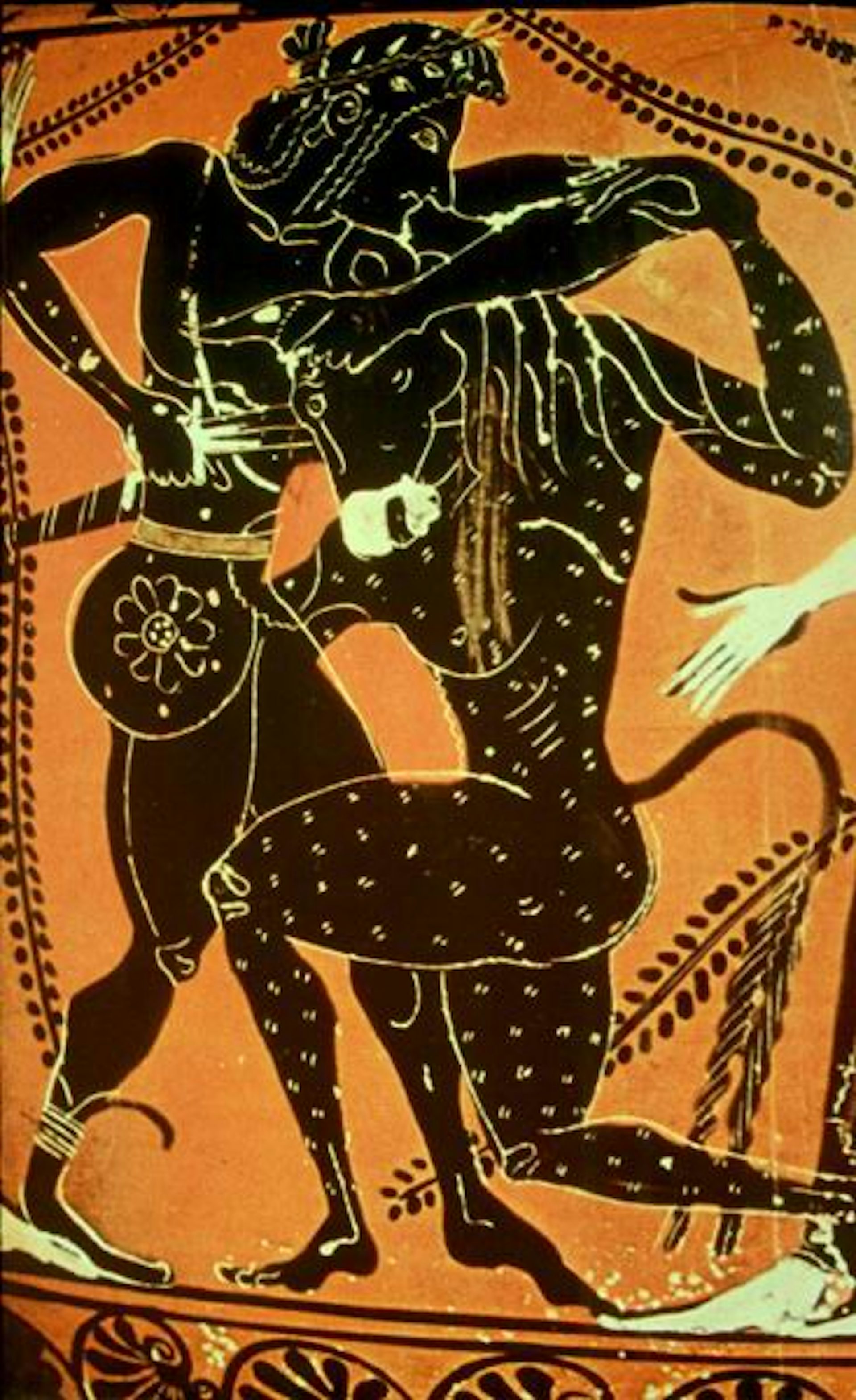

Vase painting showing Theseus and the Minotaur (6th century BCE).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainFollowing Ariadne’s instructions, Theseus entered the Labyrinth with a ball of thread, which he unwound as he traversed the twisted passages. Theseus found the Minotaur, killed it, and then followed the thread back to the exit. His mission accomplished, he escaped from Crete with Ariadne and the other Athenian tributes.[10]

Other Interpretations

Already in antiquity, some authors suggested rational explanations for the myth of the Minotaur. Some of these interpretations are preserved in Plutarch’s Life of Theseus. For example, Plutarch (quoting Aristotle) wrote that the Athenian youths were not fed to the Minotaur but simply forced to live out the rest of their lives as slaves. [11]

In another interpretation, which Plutarch attributed to certain historians, the Minotaur was actually a Cretan general named Taurus. This Taurus had won some Athenian youths as a prize in a contest and imprisoned them in a jail called the Labyrinth. Soon after, however, Taurus was accused of having an affair with Minos’ wife, Pasiphae, and was defeated by Theseus in a wrestling match (in other versions he was killed in a naval battle).[12]

Worship

Scholars used to argue that the Minotaur represented a bull god of the ancient Minoan civilization, which flourished on Crete between ca. 3000 and 1450 BCE.[13] Today, however, this hypothesis is universally dismissed.[14]

Bulls were a significant part of Minoan culture, however. Sculptures of bull heads were quite common in ancient Crete. The Minoans also perfected the extraordinarily dangerous sport of bull-leaping, which involved an acrobat leaping over a charging bull. The memory of this practice—which was non-religious—may have been preserved in the Minotaur myth.

Fresco in the Palace of Knossos depicting the sport of bull-leaping (ca. 1600–1450 BCE). Knossos, Crete.

JebulonCC0Pop Culture

The Minotaur has retained an important presence in modern pop culture, inspiring various half-man, half-bull monsters across film, television, and video games. The creature continues to appear in adaptations of the Theseus myth; however, some of these adaptations, including Mary Renault’s novel The King Must Die and the 2011 film Immortals, give a rationalized interpretation of the Minotaur, depicting him as merely a very strong man.

A unique retelling of the Minotaur myth, told from the perspective of the Minotaur rather than Theseus, appears in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The House of Asterion (published in Spanish in 1947). The Minotaur also features in Rick Riordan’s novel franchise Percy Jackson and the Olympians.