Jupiter

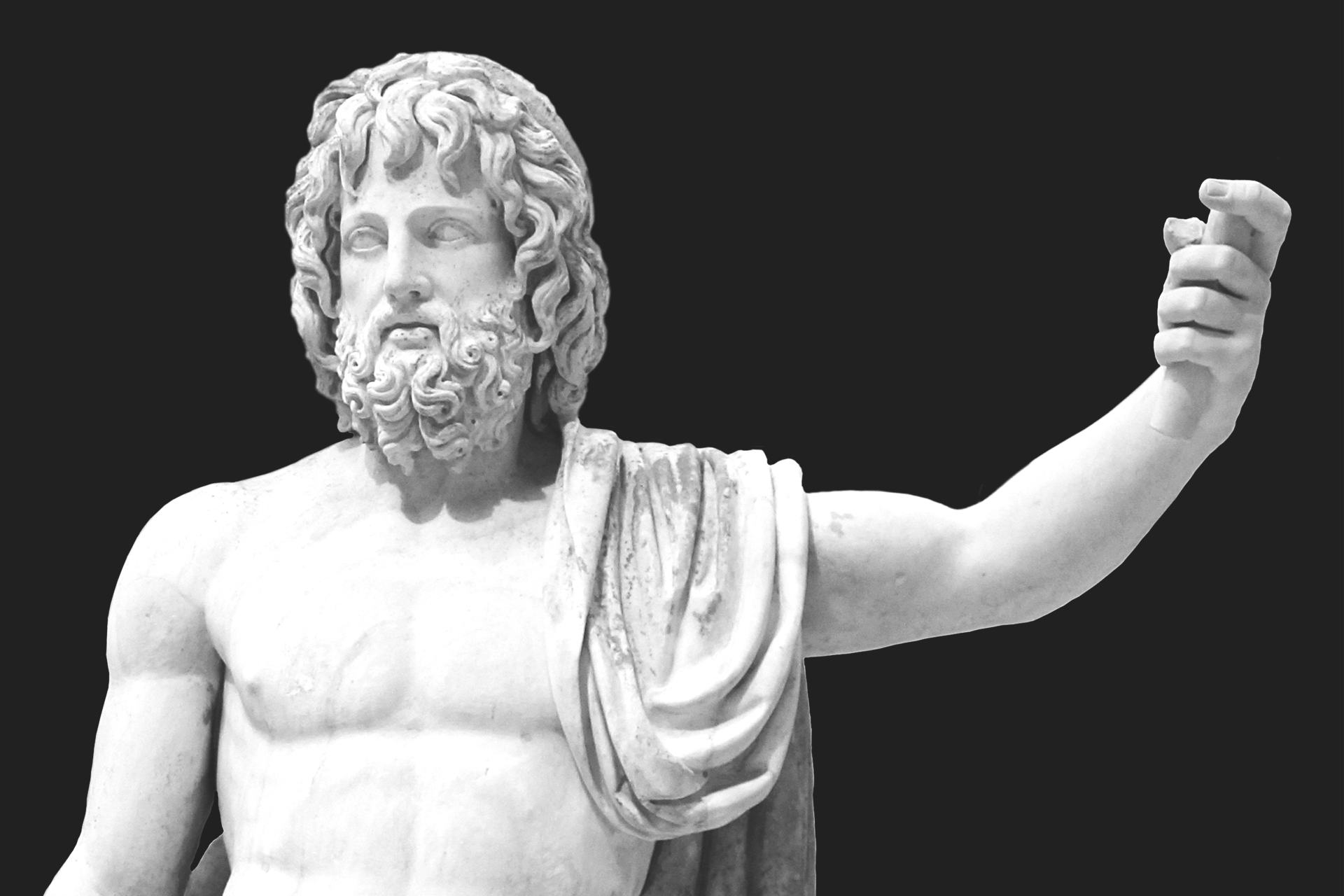

Roman statue of Jupiter (ca. 150 CE), showing the god Jupiter holding a lightning bundle (right hand) and accompanied by an eagle; he would have also held a scepter, which is now lost, in his left hand

Louvre Museum, Paris / Jean-Pol GrandmontCC BY 3.0Overview

Jupiter (or Iuppiter) was the supreme god of the Romans and Latins, a god of the sky and weather as well as a champion of world order, the state, and the Roman Empire. In mythology and art, Jupiter was largely identical with his Greek counterpart Zeus, though the two gods had separate cults.

Jupiter, like the Greek Zeus, was represented as a powerful, paternal god who wielded thunderbolts and a scepter. His worship was ubiquitous across the Roman world, with the center of his cult located in the massive temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Jupiter, bronze statue after a model by Benvenuto Cellini, probably cast by Pietro da Barga (late 16th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWho was Jupiter’s Greek equivalent?

Jupiter, the king of the Roman pantheon, was commonly identified with Zeus, the leader of the Greek gods. Though most of Jupiter’s mythology and iconography was derived from that of the Greek Zeus, the two gods had separate religious cults associated with their respective worship.

Obverse of an Attic red-figure Nolan neck-amphora (ca. 460–450 BCE) showing Zeus wielding the thunderbolt

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHow was Jupiter worshipped by the Romans?

The center of Jupiter’s cult was the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill in Rome. Here, Jupiter ruled as the dominant member of the “Capitoline Triad,” which also included his consort Juno and his daughter Minerva.

Jupiter was commonly worshipped with offerings and festivals, both at his principal temple on the Capitoline as well as at his many other temples. Roman festivals of Jupiter were quite grand and often included lavish games and sacrifices.

Sacrifice Offered before a Statue of Jupiter by Louis de Boullogne the Elder (17th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainJupiter Appears to Numa

While Jupiter’s mythology was mostly adapted from that of Zeus, there were a few uniquely Roman legends involving Jupiter’s interactions with early figures of Roman history.

In one such legend, Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, forced the woodland gods Faunus and Picus to help him summon Jupiter. During this meeting with the king of the gods, Numa agreed to teach his people how to properly worship Jupiter. In exchange, Jupiter showed Numa a spell to avoid being struck by lightning.

The Nymph Egeria Dictating the Laws of Rome to Numa Pompilius by Ulpiano Checa (19th century)

National Museum of Prado, Madrid / Poniol60CC BY-SA 3.0Roles and Powers

Jupiter was the supreme god of the Romans and Latins, familiar in at least some form to all Italic peoples.

As the god of the sky, Jupiter commanded lightning, thunder, storms, and the weather at large. Like Zeus, his Greek counterpart, Jupiter wielded thunderbolts as weapons.[1] He was also a god of rain and was thus worshipped in connection with agriculture as the god who caused crops to grow.

But Jupiter was more than just a weather god. He was seen by the Romans as the god of order in the broadest sense, embodying and upholding the world order. For instance, as the god of divination (the process by which omens were deciphered by officials known as augurs), Jupiter guaranteed that the events predicted by observable omens came to pass.[2]

By extension, Jupiter was also the god of the political and social order and the highest authority of the state. No surprise, then, that Roman emperors likened themselves to Jupiter from the time of Augustus onwards.

In addition, Jupiter presided over events such as the nundinae—days of popular assembly[3]—and served as the god of borders and alliances. He maintained the Latin League, for example, an alliance of Latin villages and tribes organized for mutual defense.

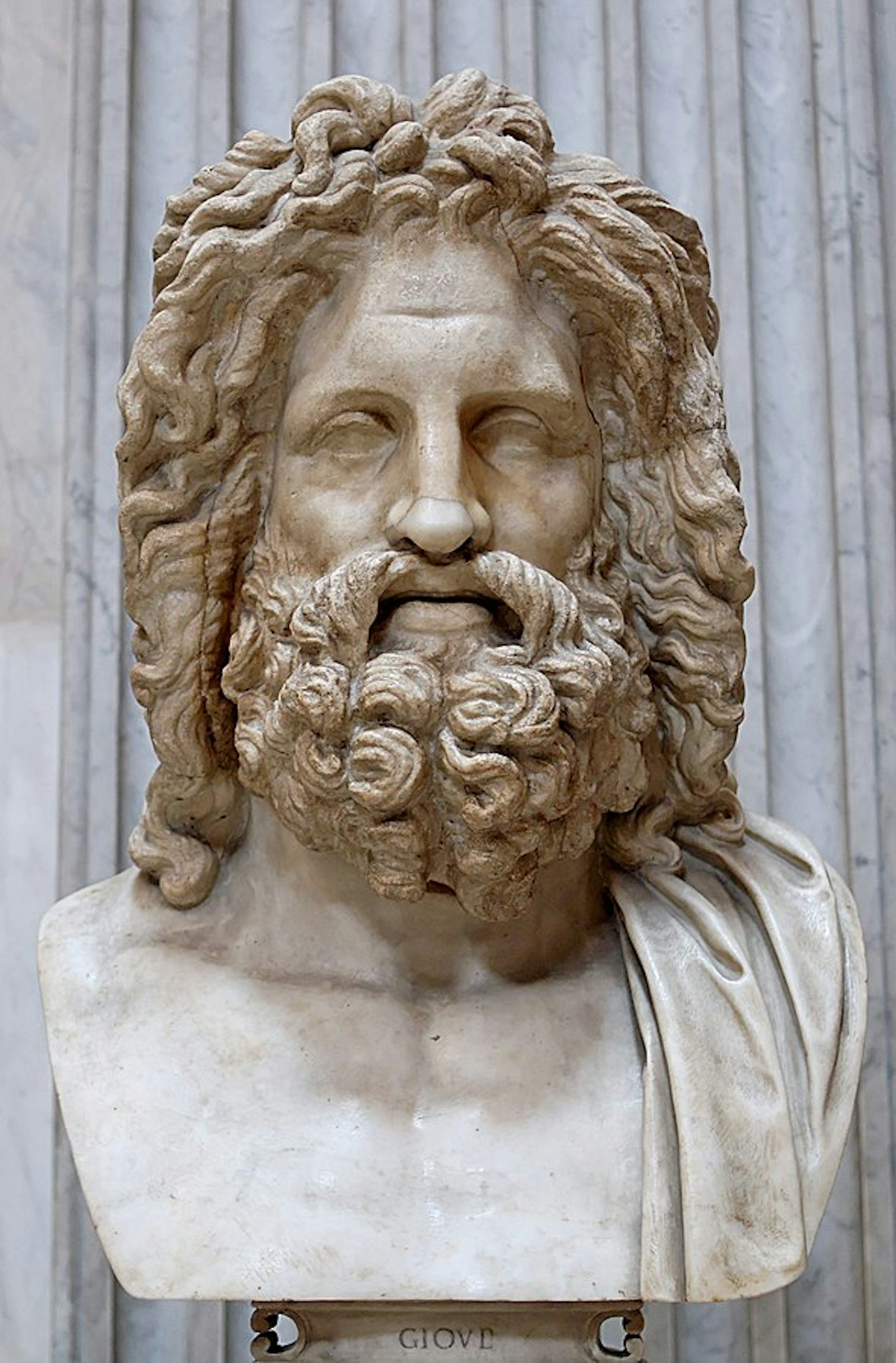

The “Zeus of Otricoli,” Roman copy of a Greek original from the fourth century BCE

Vatican Museums, Vatican / JastrowPublic DomainAmong his many other domains, Jupiter was also the god of oaths and solemn statements. The most serious oaths—those witnessed by the priests of Jupiter Feretrius and involving a ceremonial staff and a flintstone called a silex—were referred to as “swearing by the Jupiter stone.”[4]

Similarly, Jupiter presided over the confarreatio, the most formal marriage ceremony in ancient Roman society.[5] In this capacity, Jupiter was closely associated with the obscure deity Dius Fidius, also a god of oaths.[6]

Jupiter was a god of war as well, closely connected with the war god Mars from an early period. But rather than taking an active part in battles, Jupiter was thought to oversee and control them. As Jupiter Stator, for instance, Jupiter could “establish” troops and make them steadfast in battle. Roman commanders would dedicate the spolia opima—the spoils taken from an enemy commander killed in battle—to Jupiter Feretrius.[7]

More than any other deity, Jupiter held the fate of the Roman state in the balance. To appease him, Romans offered sacrifices and swore sacred oaths in his name. The faithfulness with which they made these offerings and kept their oaths is a testament to Jupiter’s status. The Romans came to believe that the success of their Mediterranean empire could be attributed to their unique devotion to Jupiter.

Attributes

Jupiter’s most notable attribute was lightning or the thunderbolt, which he wielded as the god of the sky and storms. Jupiter also held a scepter (sceptrum in Latin), a symbol of his sovereignty and power. In literature and art, he was frequently associated with the eagle.

This fragment of a sardonyx cameo, created between the first century BCE and first century CE, depicts Jupiter riding an eagle

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainBut Jupiter had many other symbols that featured in literature, art, and cult. Like other gods, he was often shown holding a patera, a shallow dish used to pour out libations. More specific to Jupiter was the silex, a flint-like stone sometimes used to symbolically strike victims sacrificed to Jupiter in a ritual context (notably at the sanctuary of Jupiter Feretrius).

Jupiter was often shown riding a quadriga, or four-horse chariot. He was also associated with white animals: his chariot, for example, was drawn by white horses, and he received white bulls as sacrificial victims.

Iconography

The earliest known representations of Jupiter closely mirrored the god’s cult image at the sanctuary of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill. In these images, Jupiter was shown standing; a cloak covered his lower body and was draped over his left shoulder, leaving his muscled torso bare; his mature face wore a thick beard; and he wielded a scepter in his left hand and a thunderbolt in his right.[8]

Though this vision of a standing Jupiter was much imitated and duplicated, many representations also depicted him seated, again bare-chested and holding a scepter and thunderbolt. Often, as in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, he would be placed between Juno (on his left) and Minerva (on his right).

Sometimes, especially during the Imperial period (ca. 27 BCE–476 CE), Jupiter would be shown with Victoria, the goddess of victory, or holding a small image of her in his hand.

Another important representation of Jupiter—this one crowning the roof of the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus—showed the god riding a four-horse chariot (the original statue, made of bronze, was eventually replaced by a bronze statue group).

In antiquity, Jupiter was shown not only in statuary but also on reliefs, coins, and cameos. He was almost always represented as he was in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus: mature, bearded, and well-built.

However, we know of some representations of the god as a youth or even a boy; for example, it seems that Jupiter was depicted as a boy in his cult image at the famous temple of Fortuna at Praeneste.[9]

During the period of the Empire, Roman emperors sought to connect themselves with Jupiter. As a result, many of them (beginning with Augustus) assumed attributes of the great god in their own iconography.[10]

Marble statue showing the Emperor Augustus is Jupiter (first half of the first century CE); he is holding an orb in his right hand and a scepter in his left hand

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg / SailkoCC BY-SA 3.0Etymology

In Latin, the name “Jupiter” was usually rendered as Iūpiter or Iuppiter (the character “j” was not a part of ancient Latin alphabet, and was added in the Middle Ages). The form Iupiter is also attested in antiquity, though it is less common. Alternative forms of the name include the archaic Diovis and the Umbrian Iupater. In English-language sources, Jupiter is sometimes also known as “Jove,” a version of the name that is derived from Iovis, the genitive form of Iuppiter. The name “Jupiter” is a combination of two elements. The first is the Indo-European *dieu-/diu-, meaning “shining thing,” “sky,” or “day,” while the second is pater, the Indo-European word for “father.” Jupiter is thus the “Day Father” (sure enough, the god’s name was sometimes given in antiquity as Dispater or Diespater, which means precisely that).

Fresco from the House of the Dioscuri in Pompeii (between 62 and 79 CE) showing Jupiter, presented here as a bearded, fully mature male, holding a scepter and staff and wearing the purple toga of royalty; the foreground of the fresco features an eagle, Jupiter's chief symbol, and a globe, symbolizing his dominion over the world

National Archaeological Museum, NaplesPublic DomainSignificantly, the first element of Jupiter’s name is also etymologically identical with that of the Greek god Zeus (who was commonly known as “father Zeus,” or Zeus pater, to the ancient Greeks). Moreover, both Jupiter and Zeus share an etymology with the name of the Old Indo-Aryan god Dyaus.

Pronunciation

English

Latin

Jupiter Iuppiter Phonetic

IPA

[JOO-pi-ter] /ˈdʒu pɪ tər/

Titles and Epithets

Jupiter had numerous epithets and cult titles (also known as epicleses) in ancient Rome. These corresponded to his myriad qualities, attributes, and roles in Roman religion, ritual, and society.

As the chief god of the state and of world order, Jupiter was known as Optimus Maximus, “best and greatest.” The cult and sanctuary of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was perhaps the most important religious center of the Roman world.

As god of the sky, weather, and thunder, Jupiter could be invoked as Caelestis (“of the heavens”), Lucetius (“of the light”—a reference either to sunlight or, as accepted by most modern scholars, to lightning), or Fulgur, Fulminator, or Tonans, all epithets that refer to Jupiter in his capacity as the god of thunder and lightning.

Another important title of Jupiter (also connected with his role as a weather god) was Elicius, probably meaning “he who is called forth (to ward off lightning),” though sometimes interpreted as “he who calls forth (lightning).”

Roman statue of Jupiter Tonans ("Jupiter the Thunderer") (1st century CE)

National Museum (Warsaw)CC0As a god of agriculture, Jupiter bore epithets such as Almus (“nourishing”), Frugifer (“fruitful”), and Farreus (“of the emmer cake,” possibly in reference to the special emmer cakes consumed during the sacralized marriage ceremony known as confarreatio).

As a god of war, Jupiter’s epithets included Victor (“conqueror”), Invictus (“unconquered”), Stator (“establisher”), and Feretrius (“he who bears away,” or, alternatively, “he who strikes down”).

Other titles of Jupiter reflected his association with specific places or with local deities assimilated to him. Examples include Jupiter Ammon (an amalgam of Jupiter and the Egyptian god Ammon), Jupiter Dolichenus (whose cult originated in Doliche, in the ancient region of Commagene), and Jupiter Indiges (“Indigenous Jupiter,” a native Latin god often identified with the hero Aeneas).

These represent only a very small selection of Jupiter’s many titles and epithets. A more comprehensive list can be found in Carl Thurin’s entry on Jupiter in the famous Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (1918).[11]

Family

Like the rest of Jupiter’s mythology, references to Jupiter’s family tended to be derived from the mythology of the Greek Zeus, with Greek gods translated into their Roman counterparts. Thus, Cronus and Rhea, the parents of Zeus, were translated into Saturn and Ops as the parents of Jupiter.

The traditional divine siblings of the Greek Zeus were likewise translated into their Roman equivalents. The Greek sea god Poseidon became the Roman sea god Neptune. The Greek Underworld god Hades (or Pluto) became the grim Roman Dis or Dis Pater (though Roman texts often simply referred to this god by the Greek name Pluto).

The Greek agriculture goddess Demeter became the Roman Ceres. The Greek Hestia became the Roman Vesta. And the Greek Hera—the maternal and domestic goddess who ruled as Zeus’ queen—became the Roman Juno, who was correspondingly named as Jupiter’s queen.[12]

Ceres Begging for Jupiter's Thunderbolt after the Kidnapping of Her Daughter Proserpine by Antoine-François Callet (1777). In this scene, Ceres asks Jupiter to free her daughter Prosperina from the clutches of Pluto, who has stolen away with her to the Underworld.

Museum of Fine Arts BostonPublic DomainRoman literary sources also followed Greek models when naming Jupiter’s offspring. Just as the Greek war god Ares was the son of Zeus and Hera, so too was the Roman war god Mars the son of Jupiter and Juno.[13] Juventas, “Youth” personified, was also a child of Jupiter and Juno, just as her Greek counterpart Hebe was a child of Zeus and Hera.[14]

The Roman fire god Vulcan, the equivalent of the Greek Hephaestus, was often listed as the son of Jupiter and Juno (though he was sometimes said to be the son of Juno alone, just as Hephaestus was sometimes represented as the son of Hera alone).[15]

The children born to Zeus from his many affairs and earlier marriages also found their way into Jupiter’s genealogy. As usual, important Greek gods were translated into their Roman counterparts. Thus, the Greek Athena, daughter of Zeus and the Oceanid Metis, became the Roman Minerva, goddess of war and crafts (and, together with Juno, one of Jupiter’s companions in the Capitoline Triad).[16]

Likewise, the Greek Hermes, son of Zeus and the Atlantid Maia, became the Roman messenger god Mercury. [17]

The Greek Apollo and Artemis, twin children of Zeus and Leto, became the Roman Apollo and Diana, gods of prophecy, healing, and the natural world (Apollo was unique in retaining his Greek name within the Roman pantheon). Their mother, in Roman sources, was usually called Latona rather than Leto.[18]

The Greek Dionysus (or Bacchus), son of Zeus and the mortal Semele, became the obscure Roman god Liber, a deity associated with wine, fertility, and freedom (the name “Liber” means “free” in Latin).[19]

The Greek strongman Heracles, son of Zeus and the mortal Alcmene, became the Roman Hercules.[20]

And the Greek Persephone, daughter of Zeus and Demeter, became the Roman Proserpina, a goddess associated with the springtime as well as the Underworld realm of her husband Dis (Hades in Greek).[21]

Though the Romans adopted the mythology of the Greeks early on, their own native mythology—largely forgotten even in the time of poets such as Virgil and Ovid (our main sources for stories of the Roman gods)—may have been very different.

For example, there is evidence that in early Latin traditions, Jupiter and Juno were the children not of Saturn and Ops but of Fortuna, the goddess of fortune or luck, who was shown nursing the two gods in a cult image in her famous temple at Praenesta (though an alternative tradition seemingly made Jupiter the father of Fortuna, rather than her son).[22]

Mythology

Origins

As a religious figure, Jupiter followed the pattern established by other Indo-European sky gods. He can thus be compared to the Vedic Dyaus, the Hurro-Hittite Teshub, the Etruscan Tinia, and, of course, the Greek Zeus. In various guises and under various names, Jupiter was worshipped by virtually all Italic peoples, though the Roman Jupiter is best known today.

Over time, Jupiter became more strongly associated with storms, thunder, lightning, and sovereignty, but he always remained, in essence, the embodiment of the boundless expanse of the heavens. Indeed, Roman poets continued to use Jupiter’s name as a synonym for the heavens well into the historical period.[23]

A fourth-style fresco from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii, showing the marriage of Zeus (right, seated) and Hera (center, standing)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / ArchaiOptixCC BY-SA 4.0If Jupiter ever had a truly native Roman or Italian mythology, that mythology is largely lost to us. Most of what is “Roman” about Roman myth centers on quasi-historical figures such as Romulus and Remus, who had relatively little to do with the gods.

From the earliest stages of Roman history, the genealogy, attributes, and stories of Jupiter were heavily influenced by the mythology of the Greek Zeus, until the two gods became all but indistinguishable (even as their cultic identities remained distinct).

Like Zeus, Jupiter rose to power by succeeding his father Saturn, who had reigned supreme as god of the sky and universe before him. Saturn corresponds to the Greek Titan Cronus, who assumed power by overthrowing his own father Uranus (meaning “sky” in Greek, and thus known in Roman sources as Caelus, from the Latin word for “sky”).

This Cronus married his sister Rhea (Ops to the Romans). But upon hearing a prophecy that he was fated to be overthrown by one of his children, Cronus decided to devour his offspring in order to protect his power. Cronus’ youngest son, Zeus, was hidden by Rhea to shield him from this fate.

Brought up in secret, Zeus eventually freed his siblings and, with their help, overthrew his father, taking his place as ruler of the universe.[24]

The Nurture of Jupiter by Jean-Baptiste Corneille (17th century)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWe find elements of this so-called “Succession Myth” in Roman sources, too, though with some key differences. Jupiter’s Italian predecessor, Saturn, is not quite the tyrant that we find in the Greek Cronus. In fact, the time of Saturn’s rule is remembered in Roman literature as a pleasant Golden Age (an idea that sometimes creeps into Greek representations of Cronus as well).

Nor did Jupiter’s accession end with Saturn being thrown into Tartarus, like Cronus was. Instead, many Roman sources tell of how Saturn escaped to Italy, where he was taken in by the two-faced god Janus. Saturn then ruled for a time as king of Italy, presiding over a peaceful Golden Age. He was still worshipped in historical times and had a very impressive temple at the foot of the Capitoline Hill in Rome.[25]

The Power of Jupiter

Jupiter’s reign over the universe was marked by order—but also, at times, by violence. Greek myths told of how Zeus, having overcome his father Cronus and the other Titans, had to fight further battles in order to cement his authority. Zeus thus fought and defeated the Giants and Typhoeus (monstrous offspring of the earth goddess Gaia), as well as other challengers, including the brash Aloads.

With these threats to his power squashed, Zeus firmly established himself as ruler of the universe, distributing authority and honors among his siblings and some of his children. These gods came to be known as the Olympians (because they lived on Mount Olympus in northern Greece).[26]

Some of these myths can be found in Roman sources as well, though they do not command the same weight as they did in the Greek world. Roman authors often confused or conflated the Olympians’ wars with the Titans, the Giants, and the Aloads, suggesting a certain carelessness or lack of interest regarding the gods’ rise to power.[27]

At the end of the day, Roman mythology was always centered on Rome—meaning the Romans’ interest in the gods only extended as far as the gods’ interest in the Romans. We therefore find that Jupiter’s most important mythical roles tended to emphasize his responsibilities as patron god of the Roman state.

Northern frieze from the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi (ca. 525 BCE) showing the Gigantomachy. The Giants are represented as hoplites.

National Archaeological Museum, Delphi / ZdeCC BY-SA 4.0The Loves of Jupiter

Jupiter, like his counterpart Zeus, was known to be a promiscuous god. Though he was married to his sister Juno, he had numerous affairs with both goddesses and mortal women. Many of the stories of these indiscretions were imported from Zeus’ mythology, but others are unique to Roman sources.

In one story, Jupiter loved the beautiful Juturna, an Italian princess of the Rutuli and the sister of Turnus, the warrior who fought Aeneas when he came to Italy. After seducing (or raping) Juturna, Jupiter transformed her into a water nymph.

But it so happened that the nymph Lara (also called Larunda) learned of the affair. Notorious for her talkativeness and for her inability to keep secrets, Lara let slip to Juno that her husband had slept with Juturna. Furious, Jupiter tore out Lara’s tongue and ordered his son Mercury to take her to the Underworld.

During the journey, Mercury raped Lara, who bore him two children. These children came to be known as the Lares—the household gods of the Romans.[28]

Mercury Embracing the Nymph Lara, engraving by Jan Harmensz (1590–1594)

RijksmuseumCC0Another legend made Jupiter the father of Scipio Africanus, the great Roman general and statesman best known for defeating Hannibal and Carthage in the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE). Jupiter transformed himself into a snake and slept with Pomponia, Scipio’s mother, in order to beget the man who would become the savior of Rome.[29]

Jupiter and Rome

Aeneas and the Founding of Rome

Jupiter is a key figure in myths and legends about the founding of Rome, beginning with the story of Aeneas, the Trojan hero at the heart of Virgil’s Aeneid.

Aeneas himself was a figure from the earliest strata of Greek mythology, one of the defenders of Troy during the decade-long Trojan War. When at last Aeneas’ city was conquered and sacked by the Greeks, Aeneas fled the city with a band of refugees and headed west to find a new home.

It seems that the idea of Aeneas as the ancestor of the Romans began circulating at a fairly early date, though it was not until Virgil’s Aeneid—composed at the end of the first century BCE—that the idea became a central part of the Roman national identity.[30]

Aeneas' Flight from Troy by Federico Barocci (1598)

Borghese Gallery, RomePublic DomainIn the Aeneid, the gods instruct Aeneas to sail to Italy after he escapes the sack of Troy. The hero is guided by his mother, the goddess Venus (Aphrodite to the Greeks), but also by Jupiter himself. In one famous passage from Book 1 of the Aeneid, Jupiter describes the great empire destined to be built by the Romans (Aeneas’ descendants), to whom the god has ordained “no bounds of empire.”[31]

Throughout the Aeneid, Jupiter is careful to keep Aeneas (and thus the destiny of the Romans) on track. Virgil writes, for example, that when Aeneas was shipwrecked on the shores of Carthage, he began an affair with the Carthaginian queen Dido; he would have stayed longer had not Jupiter sent Mercury to remind the hero that his destiny lay in Italy.[32]

At times, Jupiter would oppose his own wife, Juno, who had long hated the Trojans and who was therefore intent on destroying Aeneas. It was Juno, for instance, who caused Aeneas to be shipwrecked in Carthage in the first place. Later, when Aeneas finally reached Italy, Juno stirred up a war between him and the local Latins, led by the Italian hero Turnus.

Yet Jupiter held Juno in check, reminding her (and the other gods) that nothing could stop Aeneas and his descendants, the Romans, from achieving their destined mastery of the world.[33]

The war that Juno sparked finally ended when Aeneas defeated and killed Turnus in single combat.[34] This is where the Aeneid ends (rather abruptly). But we know from other sources that peace between the Trojans and Latins was established, just as Jupiter had predicted.

Aeneas founded a new city in Latium, which he named Lavinium in honor of his wife Lavinia. Soon after, Aeneas’ son and successor Ascanius founded another nearby city, Alba Longa. Many generations later, the twins Romulus and Remus—the founders of Rome—would eventually be born in Alba Longa.[35]

The "Lupa Capitolina," a bronze statue of the twins Romulus and Remus with the she-wolf (13th century; Romulus and Remus added 15th century)

Capitoline Museums, RomePublic DomainAccording to a popular tradition, Aeneas himself died soon after reaching Italy. In a battle at the River Numicius, not far from Lavinium, he fell in the river and drowned. The waters washed away Aeneas’ mortality and he became a god, known as Indiges or even Jupiter Indiges, the “native” Jupiter of Latium.[36]

The Kings of Rome

Numa and the Cult of Jupiter Elicius

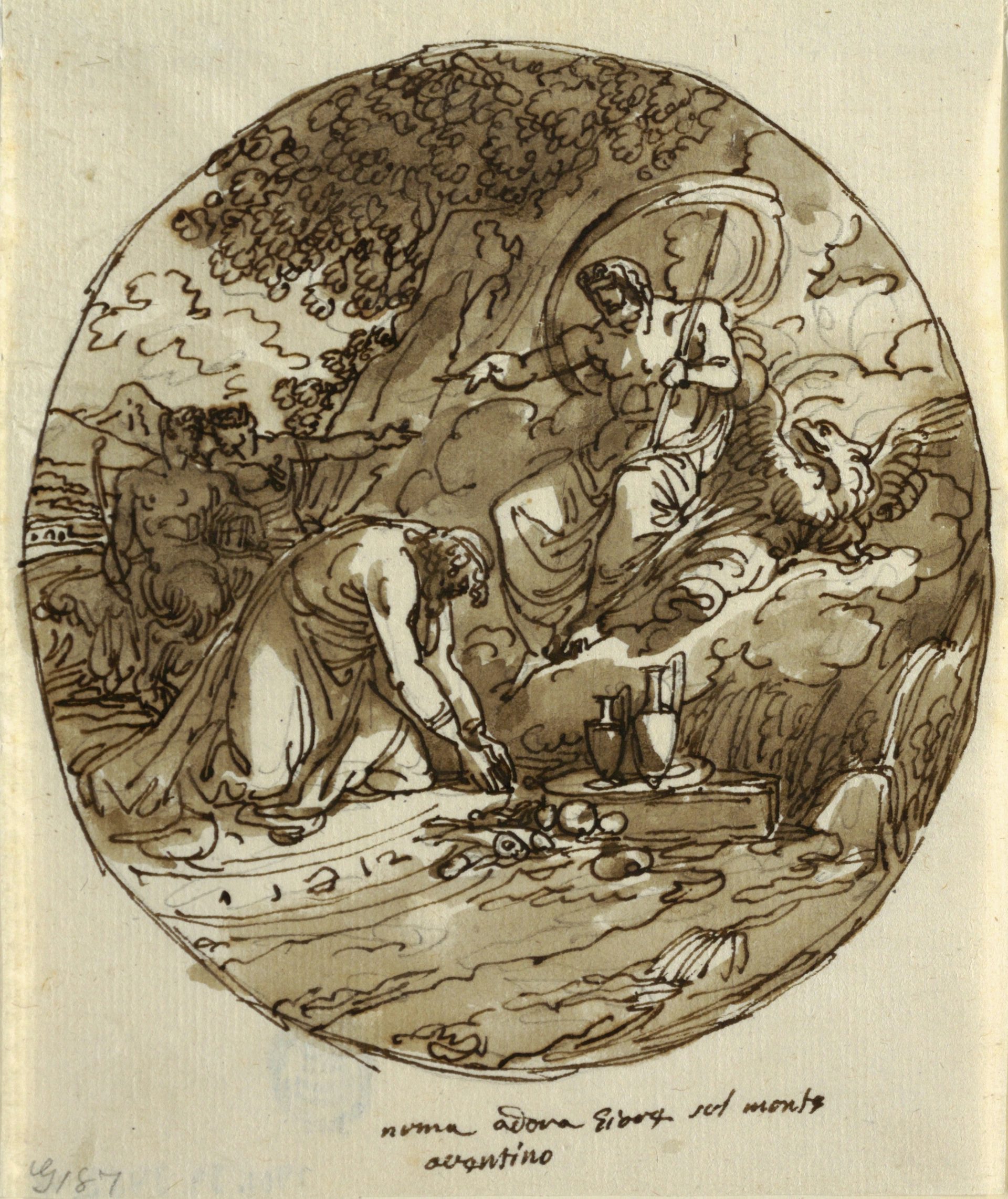

According to mythologized accounts of the founding of Rome, Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, taught the Romans how to properly worship Jupiter and the other gods. It was said that Numa was facing hardship and thus coerced the woodland deities Picus and Faunus into summoning Jupiter to the Aventine Hill. There, Numa consulted with the mighty god, who issued demands regarding the offering of hostiae (sacrifices).

In exchange for securing the worship of the Roman people, Jupiter taught Numa how to avoid lightning bolts, as per Numa’s demands (the ritual supposedly involved onions, hair, and sprats). This was the basis for the cult of Jupiter Elicius—that is, “Jupiter who is called forth (by ritual means).[37]

Numa Pompilius Worshipping Jove on the Aventine by Felice Giani (1804–1805), design for the ceiling fresco for the Sala di Numa Pompilius in the Palazzo Milzetti, in Faenza

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design MuseumPublic DomainJupiter’s lightning lesson likely served as a metaphor symbolizing his broader offer of protection and support for the Roman people. Jupiter sealed his pact with Numa and the Romans by sending down from the heavens a perfectly round shield called the ancile.

In order to deceive anyone who might try to steal this sacred artifact, Numa had eleven nearly identical copies of the ancile made. These twelve shields—known collectively as the ancilia—became a sacred symbol of the city and an enduring reminder of the pact between Jupiter and Rome.[38]

The Impiety of Tullus Hostilius

Not every Roman king, however, was as successful in winning Jupiter’s favor. In one story, Tullus Hostilius, the third king of Rome, discovered Numa’s instructions for summoning Jupiter Elicius. He tried to carry out the ritual, but his clumsy errors so angered Jupiter that the god struck him and his home with lightning, burning the impious king alive.[39]

The Tarquins and the Rise of the Roman Republic

Jupiter was also a significant figure in the legends surrounding the dynasty of the Tarquins, the last kings of Rome. It was recorded that Tarquinius Priscus, who would eventually become the fifth king of Rome, witnessed a powerful omen as he was immigrating to Rome from the Etruscan city of Tarquinia.

During the journey, an eagle—Jupiter’s bird—swooped down, snatched Tarquinius’ cap from his head, circled over the carriage with loud cries, and then replaced the cap. Tarquinius’ wife Tanaquil, a skilled interpreter of omens, understood this as a sign that the gods would make her husband a king.[40]

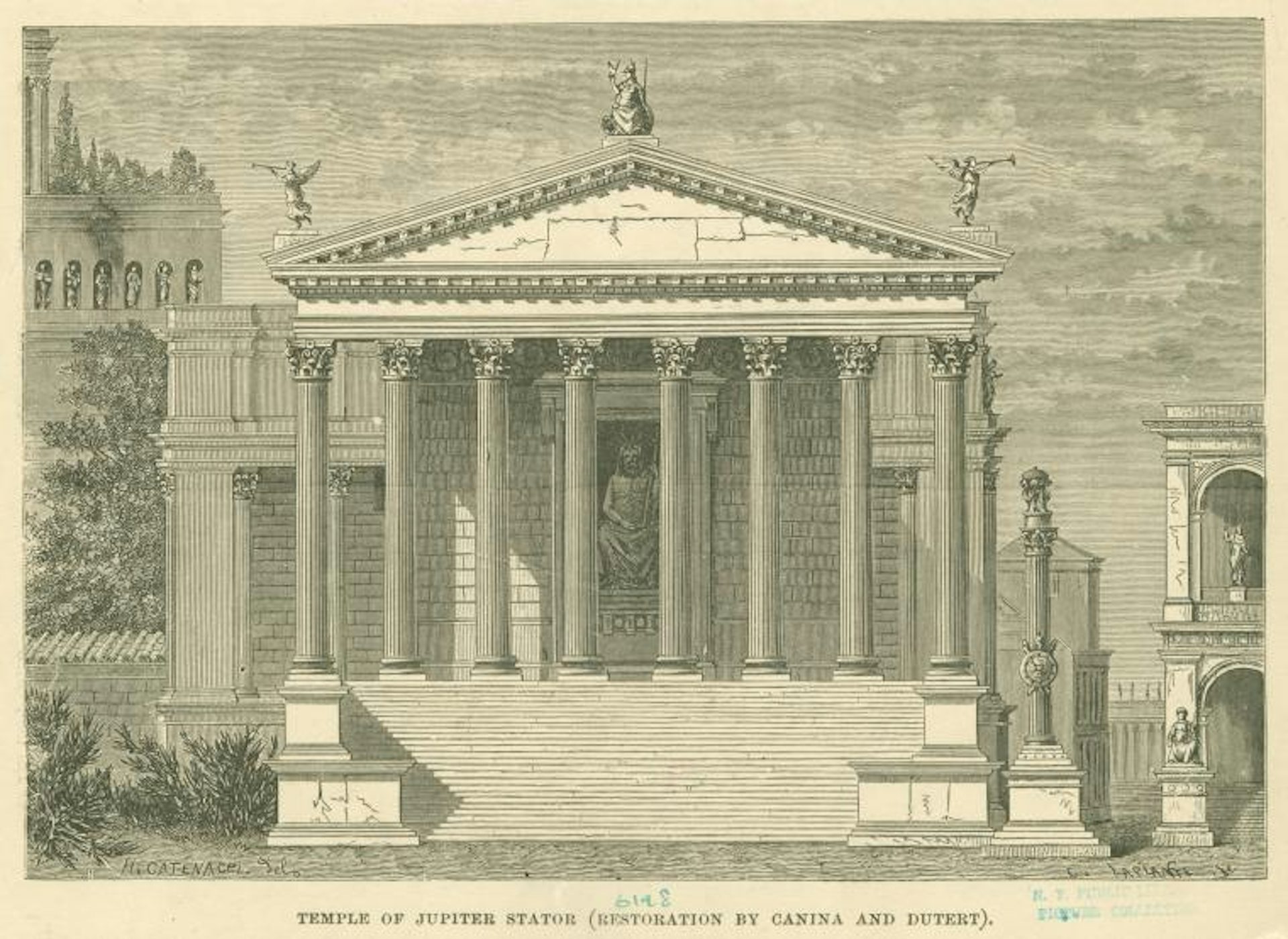

Sure enough, Tarquinius Priscus became an important king of Rome. He launched many building projects, including construction of the gigantic temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill, which remained the most important temple of Jupiter well into the historical period.[41] Tarquinius Priscus never completed the temple, however; it was continued later by his son Tarquinius Superbus, the wicked seventh (and final) king of Rome.[42]

Tarquinius Superbus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1867)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe building of the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was accompanied by two significant portents.

First, omens indicated that Terminus, the god of boundaries, and Juventas, the goddess of youth, refused to leave their Capitoline sanctuaries, which were located where the new temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was to be built. This was interpreted as a good omen, indicating that the borders of Rome would be forever stable and that Rome would always be strong and youthful. The sanctuaries of Terminus and Juventas were eventually incorporated into the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.[43]

The second omen was somewhat more dramatic: as the foundations of the temple were being excavated, workmen discovered a human head. This too was interpreted favorably, as a sign that Rome would become the head of a great empire.[44]

Bas-relief from the Arch of Marcus Aurelius, late second century CE. The background of the work provides one of the few surviving depictions of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, while the foreground depicts Marcus Aurelius and his family offering animal sacrifices to Jupiter. Capitoline Museum, Rome, Italy.

Matthias KabelCC BY-SA 3.0The temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was completed in great splendor, but Tarquinius Superbus was cast out of Rome before he could dedicate the structure. Because of this, the dedication of the temple in 509 BCE was said to have been one of the first actions of the new Republic.[45] The birth of the Roman Republic thus coincided with the establishment of the most important Roman temple.

The Republic and Beyond

Roman legend did not come to an end with the rise of the Republic. On the contrary, many of the most famous mythical stories of Rome are set in what can comfortably be regarded as historical times. The Romans themselves believed that Jupiter continued to play an active role in their history.

Jupiter was a central player, for instance, in many accounts of the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE). In one legend, Jupiter sent the Carthaginian commander Hannibal a dream telling him to march on Rome; he even gave Hannibal his son Mercury as a guide.[46] It was often said that Jupiter did this to put Rome’s military power to the test and to cement their dominance in the Mediterranean.

It was also said that Scipio Africanus, the Roman statesman and general who finally defeated Hannibal, visited the temple of Jupiter so frequently that even the temple dogs came to know him.[47] One legend even made Scipio the son of Jupiter (see above).

Scipio Africanus Freeing Massiva by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1719–1721)

The Walters Art MuseumPublic DomainLater, with the rise of Augustus and the form of government known as the Principate, Roman emperors increasingly associated themselves with Jupiter. It became common practice for the emperors to be worshipped as gods after they died, and some authors even depicted dead emperors in council with Jupiter and the other gods in heaven (though these texts were often satirical).[48]

Worship

Temples and Sanctuaries

Jupiter Optimus Maximus

In Rome, the focal point of the cult of Jupiter—and of the state religion in general—was the grand temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill. This was the greatest of all Roman temples. Though it burned down several times and was definitively destroyed in the sixteenth century, it towered over the Capitoline for over a millennia.

A statue of Jupiter driving a four-horse chariot could be found at the apex of the temple. Inside, worshippers were met with a statue of Jupiter that was painted red during celebrations, as well as a stone altar called Iuppiter Lapis (“the Jupiter Stone”), where oath-takers took their sacred vows.

The temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was erected in honor of what has been called the Capitoline Triad, composed of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. There were thus three cellae (inner chambers) in the temple, with the central cella dedicated to Jupiter, the left cella to Juno (known in this context as Juno Regina, “Juno the Queen”), and the right cella to Minerva.[49]

It is unknown how the Capitoline Triad first came about. Some scholars have tried to trace it to the Etruscans, the Romans’ neighbors to the north, but modern theories posit that the Capitoline Triad came from Greece. As evidence of this, scholars point to the triad of Zeus, Hera, and Athena (the Greek counterparts of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva), who were worshipped at the Phokikon, the main sanctuary of the Phocians in central Greece.[50]

Marble statue of the Capitoline Triad, showing Jupiter (center) flanked by his wife Juno (left) and daughter Minerva (right) (ca. 160–180 CE)

Rodolfo Lanciani Archaeological Museum, Guidonia Montecelio / ManuelarosiCC BY-SA 4.0The gigantic temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, consecrated in 509 BCE, existed for over one thousand years before gradually falling out of use at the end of the fourth century CE as paganism declined. It was finally leveled once and for all in the sixteenth century.

Over its long history, the temple burned down several times, being rebuilt each time on an even grander scale than before. The temple represented the borders of the world, with the god Terminus—the personification of borders and boundaries—being worshipped within the bounds of the temple in the form of a borderstone.[51] As Rome expanded, many Roman colonies also erected a temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on their Capitoline Hill.

The temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus served as a sacrificial site where Romans would offer slaughtered animals (known as hostiae) to the mighty god. The hostiae for Jupiter were oxen or bulls (especially white ones), lambs (offered annually on the Ides of March), and wethers or castrated goats (offered on the Ides of January).

The temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was also the final destination of the celebratory military processions known as “triumphs.” Such processions were led by a triumphator, or victorious general. The procession itself would consist of the triumphator’s army, prisoners, and spoils, which would wind through the streets of Rome before ending up at the great temple. There, the procession offered sacrifices and left a portion of their spoils for Jupiter.

The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus by Carle Vernet (1879), a painting depicting the triumphal procession celebrating the victory of the Roman general over Macedon in 168 BCE; the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus is featured prominently in the background (left of center)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThroughout these festivities, the triumphator would bear the trappings of Jupiter himself: he would ride in a four-horse chariot, wear a purple toga, paint his face red, and even carry the scepter of Jupiter.[52]

Other Temples in Italy

Besides the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Jupiter had many other important sanctuaries throughout Rome, Latium, and the rest of Italy.

As the god of storms and thunder, Jupiter was often worshipped on hills (not unlike Zeus). In terms of elevation, the sanctuary of Jupiter on the Alban Mount was the god’s highest sanctuary in the region of Latium. There were other hilltop sanctuaries of Jupiter further south—for instance, at Terracina, where Jupiter was worshipped on a cliff as Jupiter Anxur or Anxurus.[53]

At Praeneste, a city in Latium not far from Rome, Jupiter was worshipped at the major temple of the goddess Fortuna, where he was represented—quite unusually—in the form of a young boy (see above).

In Rome itself, there were sanctuaries of Jupiter on several of the hills. The temples of Jupiter Feretrius and Jupiter Stator were said to have been the oldest in the city, founded (according to legend) by none other than Romulus, the first king of Rome.

On the Aventine Hill stood the altar of Jupiter Elicius, connected with Jupiter as the god of thunder and lightning. This important altar was said to have been dedicated by Numa, the second king of Rome (see above).

On the Capitoline—the very hill dominated by the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus—there was also a temple of Jupiter Tonans (“Jupiter the Thunderer”), dedicated by Augustus in 22 BCE after he escaped being struck by lightning during the Cantabrian War. Another sanctuary of Jupiter stood on the Campus Martius in Rome.

Illustration of the restored Temple of Jupiter Stator in Rome by Hercule Louis Catenacci (1890)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThese are only a few of Jupiter’s most important Roman sanctuaries. The god boasted a host of smaller sanctuaries, too, scattered throughout Rome and the rest of Italy.

Festivals and Rituals

In Rome, Jupiter was honored with two major festivals of political unity. The first of these, the Ludi Romani, was celebrated between September 4 and 19. The festivities involved games and contests (ludi in Latin), and the main day, September 13, was marked by a sumptuous feast in honor of Jupiter, known as an epulum.

The second festival, held between November 4 and 17, also had an epulum and concluded with a great banquet on the Capitoline Hill.

As Jupiter Latiaris, or god of the Latins more broadly, Jupiter was celebrated at the Feriae Latinae, a festival held at the god’s sanctuary on the Alban Mount. This festival was considered quite ancient; legend claimed that it was founded (or renewed) by Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome.[54]

Jupiter was also honored at various wine festivals. The purpose of these festivals was to symbolically integrate wine into the world order of Jupiter, thus liberating the beverage from its harmful effects.

In Rome, there were two major wine festivals, called Vinalia. The Vinalia priora (“first Vinalia”), celebrated on April 23, marked the beginning of the vintage, while the Vinalia rustica (“country Vinalia”), celebrated on August 19, marked the tasting of the first wine.[55] Another wine festival associated with Jupiter, the Meditrinalia (held on October 11), celebrated the tasting of the first fermented grape juice.[56]

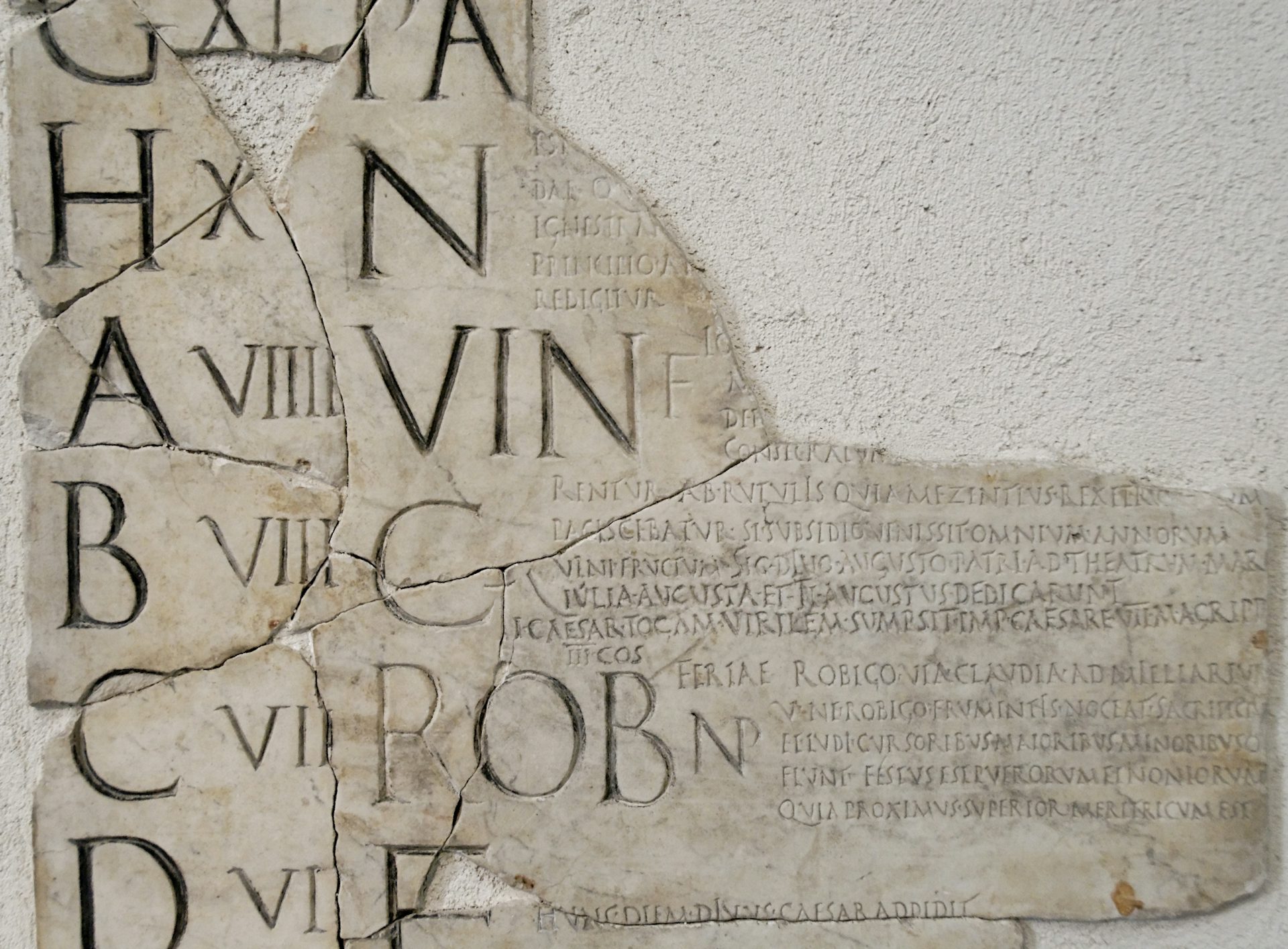

Fragmentary section of the Fasti Praenestini showing the dates for the Vinalia priora (designated VIN) and the Robigalia (designated ROB) (between 9 and 6 BCE)

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 2.5Other festivals of Jupiter were usually held on the Ides, the middle day of every month in the Roman calendar. Because Jupiter was the most important god, it was determined that he should occupy the central position in all things (for the Romans, the middle, rather than the head, was the position of honor).[57]

The Ludi capitolini, for instance—a festival of ritual inversion associated with Jupiter—was held on the Ides of October (October 13). Moreover, on every Ides, the high priest of Jupiter—the flamen Dialis—would sacrifice a lamb on the Capitoline altar.[58]

Finally, there were rituals associated with Jupiter as god of the weather and rain. The aquaelicium was a procession involving the sacred rhyolite stone, known as the lapis manalis, by which the Romans asked Jupiter to provide rain in the dry season.[59] Another rain ritual was the nudipedalia, which translates to “naked-footed”—so named because it involved women going about barefoot.[60]

Priests

Overseeing the sprawling cult of Jupiter in Rome was the flamen Dialis, the high priest of Jupiter. The flamen Dialis was one of the most important members of the college of flamines, a body of fifteen priests who presided over the affairs of the state religion. Together with the flamines of Mars and Quirinus, the flamen Dialis was one of three flamines maiores, or “great flamines.”

This connection between the priests of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus, combined with the association between the three gods in other early Roman rituals (for instance, the prayer of the fetiales), has led some scholars to posit that these gods were part of an “Archaic Triad” that was important in the earliest period of Roman religion.[61]

Marble sculpture of a flamen (between 250 and 260 CE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / JastrowPublic DomainThe flamen Dialis was one of the highest ranking figures in Roman religion, but he led a life much constricted by ceremony and religious demands. The restrictions placed on the flamen Dialis and his wife regulated every aspect of the priestly couple’s life, from where they slept to how they cut their fingernails.[62]

Foreign Cults

From a very early period, Jupiter was frequently identified with the gods of other Italian, Mediterranean, and European peoples. This identification of Roman deities and rituals with those of foreign civilizations was a common practice, sometimes referred to as interpretatio Romana.

As previously mentioned, Jupiter was identified with the Greek Zeus from an early period, adopting most of his Greek counterpart’s mythology and iconography. Jupiter was also identified with Tinia, the supreme storm god of the Etruscans.

In later periods, Jupiter assimilated the gods of many other civilizations as well, especially those conquered by the Romans or folded into their sphere of influence. The Romans thus associated Jupiter with the supreme gods of the Celts, Germans, and various Semitic peoples, among others.

This process of cultural and religious appropriation and syncretism spawned certain cults that became important in their own right, including the cult of Jupiter Dolichenus, which originated in Doliche (modern-day Turkey). Here the local high god was combined with Jupiter to produce a hybrid deity.

This hybrid god was represented in a distinctive manner, shown riding atop a bull and holding a thunderbolt in one hand and a double ax in the other (suggesting a link with the Hittite storm god Teshub).

Votive statue of Jupiter Dolichenus (2nd or 3rd century CE)

Louvre Museum, Paris / Marie-Lan NguyenCC BY 4.0During the second century CE, the cult of Jupiter Dolichenus began spreading across the empire, becoming especially prominent in the frontier regions of Britain and the Rhine-Danube. Jupiter Dolichenus even had a cult in Rome itself, on the Aventine Hill.

Worshippers of this god were called fratres (“brothers”) and were initiated into sacred feasts after undergoing a period of instruction (during which they were known as candidati); a patronus presided over each group of fratres. There were also positions outside of these groups for members known as colitores, including those who served as scribae or notarii—scribes or recordkeepers.

Another important hybrid cult was that of Jupiter Heliopolitanus, centered on the Baalbek temple complex in Syrian Heliopolis. The sanctuary of Jupiter Heliopolitanus was truly massive: at its height, it represented the largest sanctuary of Jupiter in existence. Here the god was represented as a beardless youth wearing the garb of a charioteer; he held a whip in his right hand, a thunderbolt and ears of corn in his left; and he was flanked by two bulls.

Photo of the remains of the colonnade of the Temple of Jupiter Heliopolitanus, ancient Heliopolis in Syria (modern Baalbek, Lebanon)

Giullaume PiolleCC BY 3.0Macrobius, our main source for the cult of Jupiter Heliopolitanus, emphasized the importance of the god’s oracle and revealed that the god was worshipped in close association with Venus and Mercury. However, it seems that Macrobius was confused by this Jupiter’s idiosyncratic iconography and misidentified him as Sol, the Roman sun god.[63]

Popular Culture

In modern times, Jupiter is best known for lending his name to the fifth planet from the sun, the largest in our solar system. Many individuals have also unwittingly channeled Jupiter by uttering the folksy exclamation “by Jove!”—an expression that emerged in the Middle Ages when pious Christians, who feared using the name of their own god in vain, began invoking the “false” god Jove or Jupiter instead.

In most modern adaptations of classical mythology, however, Zeus has been preferred to Jupiter, in keeping with the broader cultural preference for Greek deities over Roman ones.