Neptune

Overview

Neptune was the Roman god of waters and seas, who controlled winds and storms. Also known as Neptunus Equester, he was recognized as a god of horses and horsemanship, as well as patron of horse racing, a popular form of entertainment for the ancient Romans. In terms of his characteristics and mythology, Neptune was an exact copy of the Greek deity Poseidon.

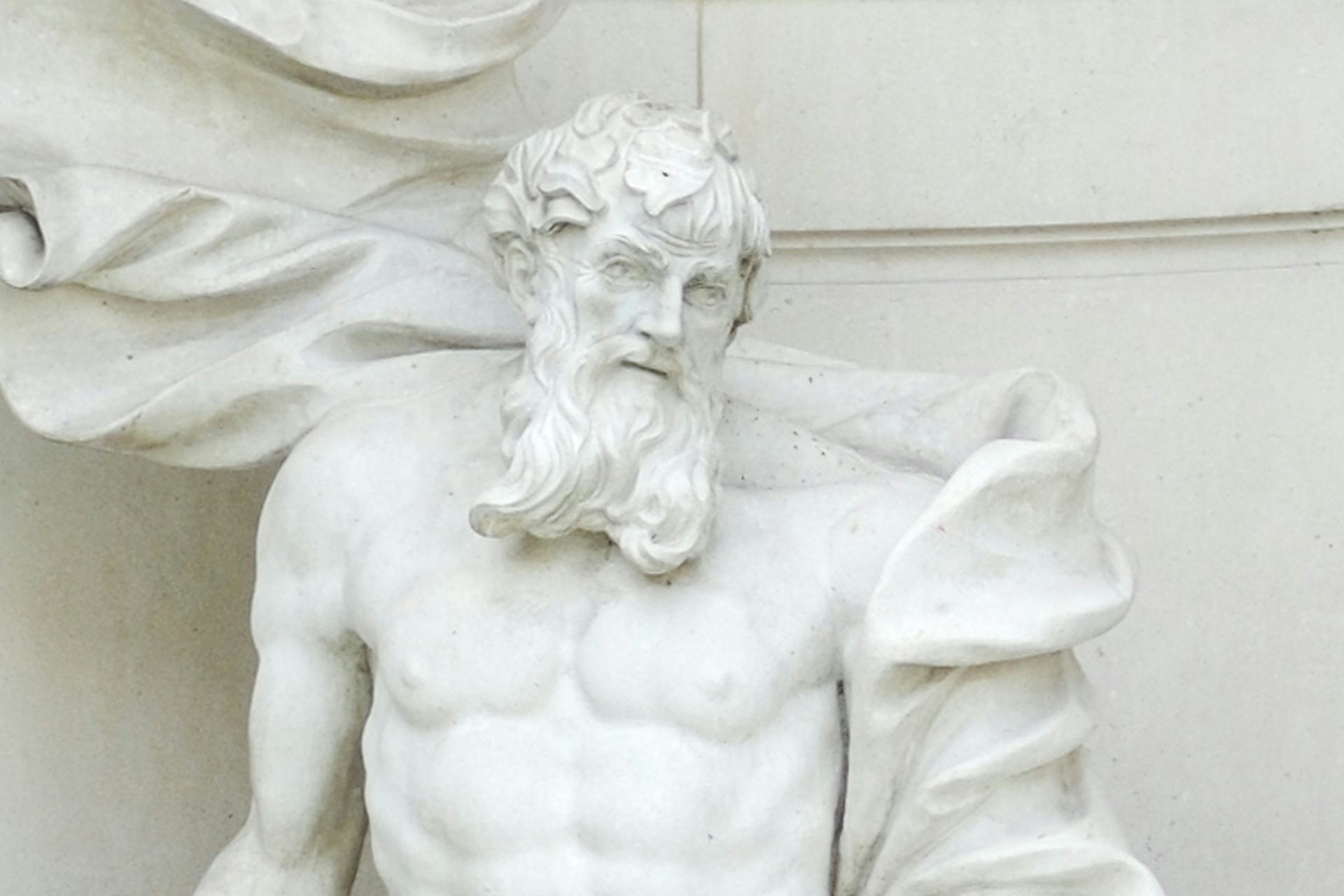

A bearded Neptune holds his signature trident, a fishing tool used by ancient cultures. Nymphenburg Palace Gardens, Munich, Germany.

no limit pictures / iStock.comUnlike Poseidon, who had been part of Greek mythology from the onset, Neptune was a later addition to the Roman pantheon. Whereas Poseidon’s subjects treated him as a kind of second-in-command to Zeus, Neptune was never a ruling deity. He was not represented in either the Archaic Triad of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus (the deified figure of Romulus, the founder of Rome) or the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

Though he lacked political power within the Roman pantheon, Neptune still commanded the fear and respect of a people whose fortunes were intimately tied to the seas. His importance increased in the second and third centuries BCE as Roman hegemony spread throughout the Mediterranean. As with other Roman deities, Neptune’s importance diminished in the early centuries of the Common Era, and fell completely out of favor with the advent of Christian dominance over the Roman Empire in the fourth century.

Etymology

The name “Neptune” (Neptunus in Latin) was derived from an Indo-European root, although which one has been a subject of dispute. There are two candidates with strong cases. One was the word neptu-, meaning “moist or wet.” Were this Neptune’s root, the literal translation of the name would mean something like “the moist one.” Such a translation would align with Neptune’s power over water. The other candidate, nebh-, meant “cloud, mist, or fog”. This root aligned not only with Neptune’s control of water, but with his control of storms as well. He was also known as Neptunus Equester, “the moist” or “cloudy horse lord.”

Attributes

Neptune controlled all waters, from the smallest streams and springs to the largest well-known bodies of water—namely, the seas (the Romans were aware of the ocean beyond the Iberian peninsula, but only dimly so). Neptune made the Mediterranean Sea his domain, and lived in a golden palace beneath the waves with his consort Salacia and his loyal sons.

Neptune could also summon winds and storms. By roiling the seas and delivering crushing waves, Neptune sunk many ships and sent many sailors to watery graves. While he was truly mighty in his own domain, Neptune’s power waned the further he was from the seas.

“The Triumph of Neptune,” a late 2nd century CE mosaic from La Chebba, Tunisia. The central scene depicts a bearded Neptune riding in a chariot pulled by sea horses; he is flanked by his sons Triton and Proteus. The corners of the mosaic feature women and agricultural scenes representing the four seasons. As bringer and withholder of water, Neptune would have held agency over seasonal change. Bardo National Museum, Tunis, Tunisia.

Tony HisgettCC BY 2.0Neptune was thought to wield a trident—a three-pronged thrusting weapon used by Mediterranean fisherpeople for centuries. Many depictions of Neptune also featured him riding a chariot pulled either by horses or mythical seahorses; the latter were generally portrayed as horses with fish-like bodies and fins.

Family

Neptune’s father was Saturn, a mighty being who served as lord of the universe. His mother was Ops (or Opis), a primordial goddess of the earth.

His siblings were among the chief deities of the Roman pantheon. His brothers were Jupiter, king of the gods, and Pluto, the god of the underworld and wealth. His sisters were Ceres, goddess of agriculture and cereals, Vesta, goddess of the hearth and home, and Juno, goddess of marriage, family, and domestic tranquility.

In this 17th century work from German artist Hans Ulrich Franck, Neptune and his consort Salacia spur their chariot across the sea.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAlthough the precise nature of their relationship was unclear, Neptune’s consort was Salacia, a goddess associated with salt waters. Salacia served as the Roman counterpart to Amphitrite, the sea nymph of Greek lore. Together, Neptune and Salacia had four children: Benthesikyme, Rhodes, Triton, and Proteus. Of these children, Triton and Proteus were the most notable—Triton for being a sea god like his father, and Proteus for having the gift of foresight.

Family Tree

Mythology

By and large, the Roman deities were less distinct and defined in comparison to their Greek counterparts. This was particularly true of Neptune, who joined the Roman pantheon much later than other key deities. According to some calculations, Neptune did not emerge as a deity of common worship until the fourth century BC—nearly four hundred years after the founding of Rome. There are indications, too, that Neptune’s precise role in the Roman mythos was unclear for centuries following his introduction. Despite Neptune’s late arrival, many Roman authors presented him as an original member of the Roman pantheon and an important player in the founding of Rome.

The Birth of Neptune

According to the myths the Romans borrowed from the Greeks, Neptune came into the world during a time of struggle and upheaval. Neptune’s father, Saturn, had only recently unseated his own father, Caelus, as ruler of the universe. When Saturn, still immature in his powers, learned of a prophecy predicting his downfall at the hands of one of his children, he responded with murderous fury. When Saturn’s wife, Ops, delivered her first sons and daughters into the world, Saturn swallowed them one by one. Neptune was devoured instantly.

Ops managed to save her last child, however, and hid him away that he might grow to manhood and one day challenge her tyrannical husband. In his place, Ops presented Saturn with a rock dressed in swaddling clothes. When Saturn ate the rock, he came down with an excruciating stomachache that eventually caused him to vomit up his children. Neptune came again into the world, this time less favorably disposed towards his father. Joining forces with Jupiter, the child who had been saved by Ops, Neptune and his siblings joined forces and overthrew their despotic father. When Jupiter, Pluto, and Neptune drew lots to determine the domains they would rule, Neptune picked the sea.

Neptune and the Seas

According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses composed during the early years of the Common Era, Neptune determined the contours of the earth by shaping the sea floor, as well as the valleys through which rivers and streams flowed:

Neptune himself strikes the ground with his trident, so that it trembles, and with that blow opens up channels for the waters. Overflowing, the rivers rush across the open plains, sweeping away at the same time not just orchards, flocks, houses and human beings, but sacred temples and their contents.

In his zeal, Neptune drowned the whole world:

Any building that has stood firm, surviving the great disaster undamaged, still has its roof drowned by the highest waves, and its towers buried below the flood. And now the land and sea are not distinct, all is the sea, the sea without a shore.[1]

The destruction caused by the flood left only one man and one woman alive. Eventually, the “great king of the seas” allowed his son Triton to blow his mighty conch and signal the waters to recede. The raging waters subsided, leaving the earth with its contours as they were known to the Romans.

In a scene taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses, Neptune creates the flood waters that shall destroy the world.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainNeptune, Aeneas, and the Founding

Neptune also figured prominently in Virgil’s Aeneid, a work of the late first-century BCE that placed the founding of Rome in the sweep of Mediterranean history and cast Romans as the rightful heirs to Greek civilization. Virgil’s epic began with Aeneas battling a furious storm at sea as he struggled to find safe harbor. Juno, the queen of the Roman deities, had sent the storm, and in doing so had encroached upon Neptune’s domain. Her brazen disregard for his power angered the sea god. Whispering calming words, Neptune settled the seas and allowed Aeneas to proceed:

Neptune saw the sea in turmoil of wild uproar, the storm let loose and the still waters seething up from their lowest depths. Greatly troubled was he, and gazing out over the deep he raised a composed countenance above the water’s surface ... and swifter than his word he calms the swollen seas, puts to flight the gathered clouds, and brings back the sun.[2]

In this 18th century Italian illustration of Virgil's Aeneid, Neptune calms a storm to aid the hero Aeneas on his journey.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainNeptune came to Aeneas’ aid once again after the adventurer had parted from his lover—the enchanting queen Dido of Carthage. This time, however, Neptune demanded sacrifice in exchange for his assistance. In order to see Aeneas safely to Italian shores, where he would found the Roman dynasty, Neptune demanded the life of Palinurus, the captain of Aeneas’ vessel. Noble Palinurus met his end beneath Neptune’s waves after falling asleep at the helm and crashing into the sea. Now propitiated, Neptune proceeded to guide Aeneas safely to Italian shores.

Neptune and the Roman State Religion

Despite his prominent role in the Roman pantheon as a brother of Jupiter and Juno, Neptune was not a broadly worshiped deity. Because he was incorporated into the Roman cosmology later than other deities, the Romans were often unsure of his agency and power. One persistent line of thought held that Neptune was a god of freshwater and declared his consort Salacia to be the goddess of salt water. Until the first century BCE, Roman admirals credited Fortunus, a god of luck, with their naval victories. Neptune’s influence, meanwhile, went largely unrecognized.

Romans worship and sacrifice to Neptune, possibly during the Neptunalia festival.

Bauhaus 1000The Romans devoted only one major celebration to their sea god—the Neptunalia, held annually at the end of July (known as Quintilus, or “fifth month,” prior to the introduction of the Julian calendar). Held during the hot and dry period of the Mediterranean year, the Neptunalia was a plea for rains and water. The festival featured ludi—gruesome gladiatorial games and animal fights.

Pop Culture

Neptune had survived in popular culture as the name of the eighth planet from the sun. Among its numerous moons are Triton and Proteus, which bear the names of Neptune’s sons. A type of submarine known as the Neptune is also available for commercial use.

Vestiges of the Roman god have also lingered in the stereotypical image of the sea lord. A common trope in art and literature, the sea lord often appeared as a bearded figure with seaweed hair and a regal triton. The character of King Triton in Disney’s The Little Mermaid (1989) is both an example of this trope and Neptune’s lasting influence.