Amazons

Roman statue of a wounded Amazon (1st or 2nd century CE)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainOverview

The Amazons were a race of warrior women famous for their military prowess and bravery. The Greeks, whose society (and mythology) was dominated by the ideal of the male warrior, grudgingly referred to them as “equal to men.”

The Amazons lived somewhere at the edge of the Greek world, around the Black Sea, in a city called Themiscyra. They were ruled by queens said to have been descended from Ares, the god of war.

The adventures and military expeditions of the Amazons brought them into conflict with many of the greatest Greek heroes, including Heracles, Bellerophon, Theseus, and Achilles. The female-dominated, fiercely independent Amazons were commonly viewed by the Greeks as a foil to their own male-dominated world.

Where did the Amazons live?

The Greeks generally imagined the Amazons as living near the Black Sea. By the Classical period, most sources referred to the homeland of the Amazons as Themiscyra, a city by the mouth of the Thermodon River on the southern coast of the Black Sea.

Historians and archaeologists have long debated whether (or to what extent) the Amazons were based on real warrior women who lived in the Caucasus and the Eurasian steppes. Even if there is some historical truth to their existence, the city of Themiscyra was no doubt a mythical invention, as were most of the myths about the Amazons and their adventures.

Detail from a relief depicting a Greek warrior pursuing an Amazon and grabbing her by her hair. Archaeological Museum, Piraeus, Greece.

George E. KoronaiosCC BY-SA 4.0How did the Amazons reproduce?

The Amazons were an all-female society, with no male members whatsoever. Thus, when they wanted to become pregnant, they slept with men from neighboring tribes. Later, after giving birth, the Amazons kept only the girls and sent the boys back to their fathers.

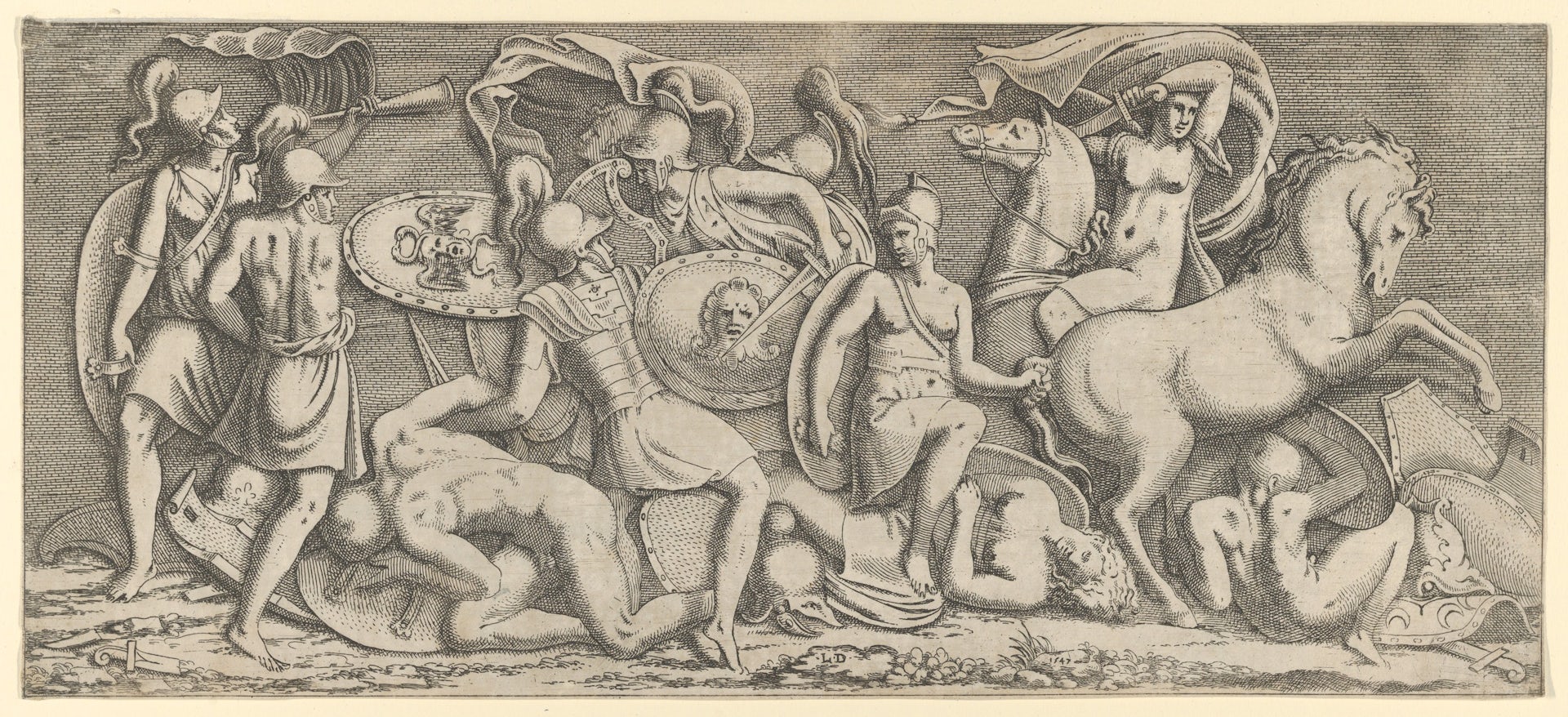

Battle of Amazons by Léon Davent (1547)

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainWho was the leader of the Amazons?

The Amazons were a society of warrior women ruled by a series of queens. These queens were described as daughters or descendants of Ares, the Greek god of war.

Famous Amazon queens included Hippolyta, whose coveted girdle was stolen by Heracles; Antiope, who was abducted by Theseus; and Penthesilea, an ally of Troy during the Trojan War who was killed by Achilles.

Amazon Preparing for Battle (Queen Antiope or Hippolyta), or Armed Venus by Pierre-Eugène-Emile Hébert (model ca. 1860/1872, cast by 1882)

National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., United States)Public DomainThe Amazons’ Invasion of Athens

Greek mythology is full of tense encounters between the Amazons and various Greek heroes. In one important tradition, the Athenian hero Theseus carried off an Amazon queen (named either Antiope or Hippolyta, depending on the version) and took her back to Athens to be his wife.

The Amazons immediately launched an invasion of Athens to bring their queen home. They devastated the countryside, wreaking havoc on the Athenian army. Eventually, the war ended when Antiope (or Hippolyta) made peace between the two sides—or, alternatively, when she died in battle.

Roman statue of a dying Amazon on horseback (second century CE)

National Archaeological Museum, Naples / Elliott BrownCC BY 2.0Etymology

The etymology of the name “Amazon” or “Amazons” is uncertain.

Among the ancient Greeks, a popular folk etymology derived the name from the word amazos, meaning “breastless.”[1] This was connected with the belief that the Amazons cut off their right breasts to make themselves more effective fighters.

Other ancient folk etymologies suggested that the Amazons got their name because they were amaza—that is, “without bread”—eating only tortoises, lizards, and snakes.[2] Others suggested the name came from amazoosai, meaning “living together.”[3]

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Amazon, Amazons Ἀμαζών, Ἀμαζόνες Phonetic

IPA

[A-muh-zaan, -zaanz] /ˈæm əˌzɑn, -zɑnz/

Alternate Names

According to Herodotus, the Scythians (warlike tribes that lived around the Black Sea) referred to the Amazons as Oiorpata. This supposedly translates to “man-killers” in the Scythian language.[8]

Titles and Epithets

The earliest attested epithet of the Amazons was antianeirai, “equal to men.” This epithet came to define the warlike Amazons, who often rivaled the most impressive male heroes of Greek mythology. Other epithets for the Amazons included androktones, androloteirai, and androphonous, all different ways of saying “man-slaying;” styganōres, “man-hating;” and philippoi, “horse-loving.”

Attributes

The foremost attributes of the Amazons were their bravery, independence, and warlike nature. Their entire lives were dedicated to war and the war god Ares, from whom they claimed descent.

Some myths about the Amazons were particularly outlandish. A common (if controversial) belief was that the Amazons cut off their right breast so that it would not get in the way when they used their bows or spears.[9]

Nolan-neck amphora showing a male warrior fighting an Amazon in exotic military dress. Attributed to the Dwarf Painter and dated to ca. 440–430 BCE.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainHomeland

The earliest sources were vague about the homeland of the Amazons. Epic authors seem to have located them somewhere beyond Thrace and Troy, where their military activities brought them into conflict with the Trojans and the Greek hero Bellerophon.[10]

During the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, the Amazons were increasingly associated with the region of Scythia, located north of the Black Sea. It became common for artists, for example, to depict the Amazons in Scythian dress.

By the fifth century BCE, however, the Greeks had invented a more definite location for the Amazons: Themiscyra, a town on the southern coast of the Black Sea near the mouth of the Thermodon River. It was soon widely accepted that this was the Amazon homeland.[11]

Even after the Amazons came to be associated with Themiscyra, certain details remained hazy. Some authors, for example, imagined that the Amazons had originated somewhere on the northern coast of the Black Sea before heading south to Themiscyra.[12] Others reversed the migration, so that the Amazons originated in Themiscyra but later moved north, to the region around Scythia and the modern-day Sea of Azov.[13]

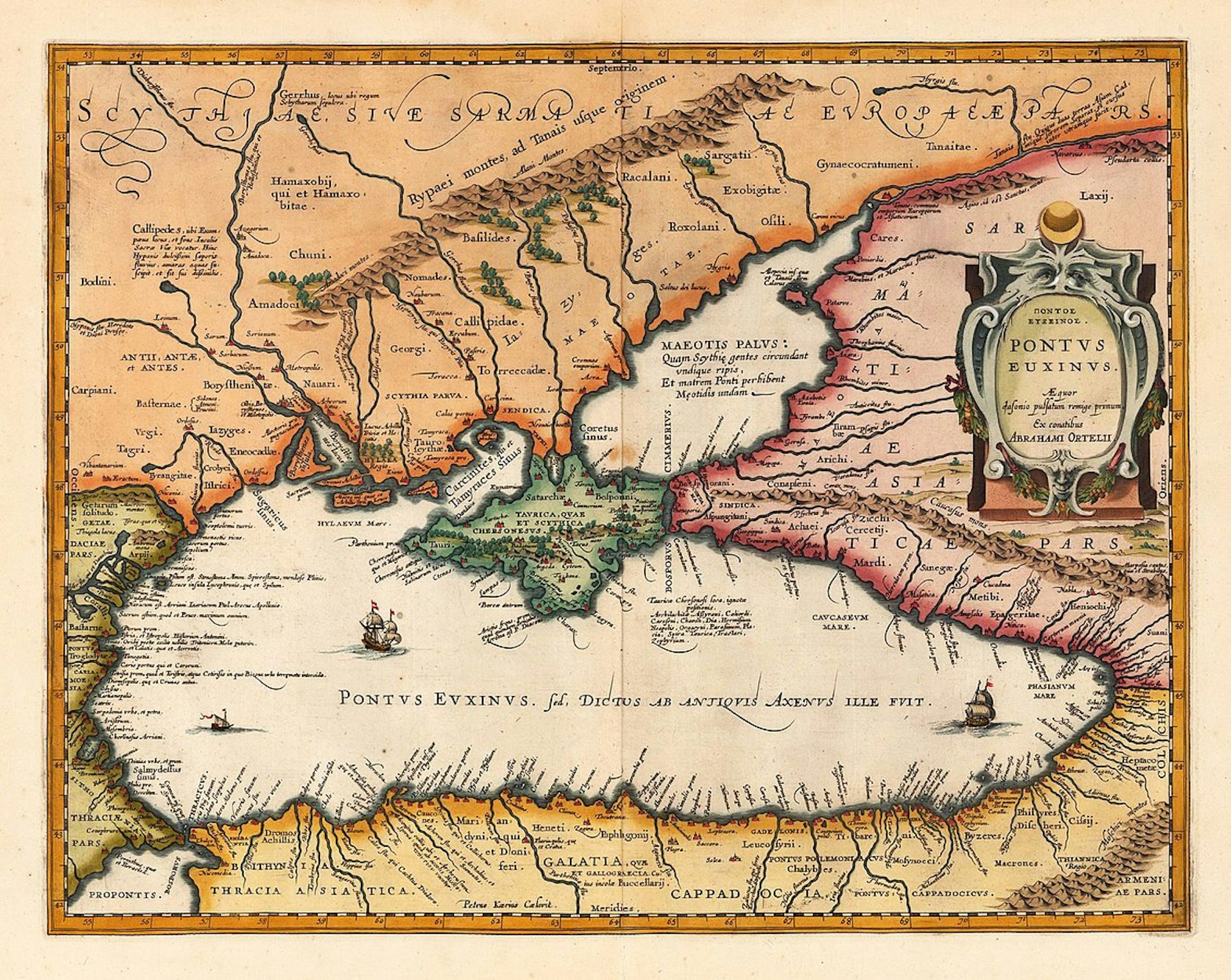

Map of the Black Sea and surrounding areas, drawn by Abraham Ortelius (1590). Many regions and cities known from Greek history and myth are represented, including Scythia (top left, in orange) and the Amazon city of Themiscyra, shown between the rivers Iris and Thermodon (bottom right).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainSome sources further subdivided the land of the Amazons into geopolitical units. In the epic the Argonautica, for example, the third-century BCE poet Apollonius of Rhodes claimed that the Amazons living on the Thermodon River were divided into three tribes: the Themiscyreians, the Lycastians, and the Chadesians.[14]

The Amazons were also regarded as the founders of several cities on the coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), including Cyme, Ephesus, Myrina, and Smyrna.[15]

Lifestyle

Wherever they made their home, the Amazons had a very distinctive way of life. All Amazon women were trained to hunt, ride, farm, and—most importantly—fight. Their society was matriarchal and matrilineal, with a queen representing the highest source of power and authority. Their most important gods were Ares and Artemis.

The Amazons lived without men. According to Strabo, they used the neighboring, all-male tribes of the Gargarians to procreate and ensure the continuation of their race. Every year, the Amazons would spend a few months with the Gargarians, choosing consorts for the purpose of becoming pregnant. After the children were born, they would keep the girls but send all boys back to their fathers.[16]

Mythology

Origins

According to the common myth, the first Amazon queen was named Otrera. In some traditions, Otrera was the daughter of the war god Ares and the nymph Harmonia (not to be confused with Ares’ daughter Harmonia).[17] In others, she was herself a lover of Ares and by him the mother of the Amazon queens.[18]

The Phrygians, Bellerophon, and Dionysus

The early adventures of the Amazons are largely obscure. The Iliad mentions a war between the Amazons and the Phrygians, during which the young Trojan king Priam fought on the side of the Phrygians.[19] The Greek hero Bellerophon, most famous for slaying the Chimera, also battled and defeated the Amazons.[20]

The Battle of the Amazons by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder (ca. 1600). Sanssouci Picture Gallery, Postdam, Germany.

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainThe Amazons also encountered the god Dionysus in several myths—sometimes as allies, and other times as adversaries.

In one tradition, Dionysus drove the Amazons from Ephesus, a city on the coast of Asia Minor, to the island of Samos. There, he proceeded to fight and kill many of them. So much blood was shed in the battle that the site was named Panhaema (meaning “Blood-Drenched” or, more literally, “All-Blood”).[21]

In other traditions, the Amazons were allied with Dionysus in his various adventures. According to Diodorus of Sicily, they helped him fight the Titans, led by Cronus, in northern Africa.[22] The military historian Polyaenus wrote that the Amazons also helped Dionysus when he fought the Indians.[23]

The Ninth Labor of Heracles

The great hero and strongman Heracles had to face the dreaded Amazons for one of his Twelve Labors (the ninth labor, according to the canonical sequence). Heracles was sent to retrieve the magical girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyta.

In many traditions, this labor was another of Heracles’ hack jobs: the hero sailed to the land of the Amazons, demanded the girdle, and killed Hippolyta and her Amazon warriors when they resisted.

But there was one version of the myth in which Heracles nearly convinced Hippolyta to hand over the girdle peacefully. The fighting could have been avoided entirely, but Hera, Heracles’ most resolute enemy, wanted blood. Thus, she disguised herself as an Amazon and convinced Hippolyta’s warriors that Heracles was planning to lure Hippolyta into a trap. A fight broke out, in which many Amazons (including Hippolyta, in some versions) were ultimately killed.

In both versions, Heracles ultimately took the girdle and sailed back to Greece.[24]

Lekythos showing Heracles' battle with the Amazons, attributed to the Haimon Painter (ca. 480 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainTheseus and the Athenians

The travels of the Athenian hero Theseus took him to the land of the Amazons as well. In some traditions, he traveled there with Heracles to help him carry off Hippolyta’s girdle, but in most accounts this was a separate adventure.

Theseus fell in love with the Amazon queen—usually called Antiope,[25] but sometimes cited as Hippolyta,[26] Melanippe,[27] or Glauce[28]—and took her back with him to Greece (whether she went willingly or by force varied by the source). The Amazons were furious and attacked the Athenians in order to retrieve their queen.

The resultant war nearly destroyed Athens. The Amazons besieged the city and proved more than a match for Theseus and his army. In the common tradition, the war only ended when Antiope was killed in battle.[29]

The Trojan War

The Amazons had one more famous encounter with the Greeks. In the tenth and final year of the Trojan War, the Amazons came with a small but well-trained force to help the city of Troy defend itself against the Greek army. They were led by their queen, Penthesilea (who, like other Amazon queens, was a daughter of Ares).

Penthesilea briefly wreaked havoc on the Greek army. Eventually, however, she was slain by Achilles, the greatest of the Greek heroes at Troy. After killing Penthesilea, Achilles took pity on the beautiful young queen (in some traditions, he even fell in love with her). But it was too late: Penthesilea was dead.[30]

Between Myth and History

Rationalizing the Amazons

Even in antiquity, many wondered about the historical reality of the Amazons.

Palaephatus, a paradoxographer (that is, a kind of professional “myth-buster”), insisted that the Amazons never existed—or at least, not in the form popularized by myth. He claimed that the “Amazons” were actually male warriors who were sometimes mistaken for women because they shaved their beards, wore long gowns, and tied their hair into headbands.[31]

But Palaephatus was unable to convince many of his contemporaries. Most ancient authorities appear to have regarded the Amazons as at least partly historical.

Scythia and Beyond

Herodotus, one of the earliest Greek historians, claimed that the Amazons originated in Themiscyra, on the Thermodon River, but eventually reached the north coast of the Black Sea on Greek ships. There, they mingled and assimilated with the Scythians who inhabited the region, thereby becoming the ancestors of the Sauromatians, one of the Scythian tribes.[32]

Centuries after Herodotus, the geographer Strabo recorded the belief that the Amazons inhabited the mountains of the Caucasus, north of the Black Sea (this belief persisted even to his day, the second century CE). Though Strabo expressed some skepticism about the Amazons, he never explicitly denied their existence.[33]

Another Greek historian, Diodorus of Sicily, described the histories of a few different groups of Amazons. The most familiar group—the Amazons who battled the Greek heroes and took part in the Trojan War—lived by the Black Sea.[34] But Diodorus spoke of another race of Amazons that lived in Libya, also fearsome warrior women. According to Diodorus, they fought wars against several ancient powers, including the Atlantians and the Gorgons.[35]

Alexander the Great

Some imaginative ancient authors (along with a handful of less reputable historians) even claimed that the Amazons encountered Alexander the Great during his campaigns in the fourth century BCE. This may be the best illustration of how persistent the Amazon myth remained even well into the historical period.

The Amazon Queen, Thalestris, in the Camp of Alexander the Great by Johann Georg Platzer (mid-18th century).

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainAs the story usually went, Alexander the Great met the Amazons while campaigning in Thrace, an ancient region located in the northeastern Balkans. The Amazon queen Thalestris supposedly approached Alexander herself, hoping to have a child by him who was as strong and brave as he.[36]

Modern Archaeology

Archaeologists and historians have unearthed more and more evidence to suggest that the myth of the Amazons was built upon an underlying kernel of truth. In southern Ukraine and Russia, numerous graves have been found with the bodies of armed warrior women. Many of these are located in the territory of the ancient Sarmatians—almost certainly the same tribe as the Sauromatians that Herodotus connected to the historical Amazons.

Of the warrior graves discovered in this region, somewhere between 20 to 40 percent belonged to female warriors. Thus, there was almost certainly a factual basis to the Amazons of Greek mythology, even if the most memorable characters—such as Hippolyta, Antiope, and Penthesilea—were probably fictional.[37]

Worship

Greek authors mention the presence of Amazon tombs throughout the Greek world, including in Athens, Megara, Thessaly, and Asia Minor.[38] This suggests that some Amazons received special honors after their death or were even the objects of hero cult.[39]

Pop Culture

The Amazons have continued to exert a huge influence on modern pop culture. Over time, they have come to represent more than just the rivals of male Greek heroes; nowadays, Amazons are seen as a feminist symbol for the subversion of outdated gender stereotypes.

In literature, the Amazon myths have inspired a number of works. Theseus’ abduction of the Amazon queen Antiope has been the subject of several historical fiction novels, most notably Mary Renault’s The Bull from the Sea (1962) and Steven Pressfield’s Last of the Amazons (2002). Other Amazon queens, such as Hippolyta and Penthesilea, have also appeared in novels, poems, and dramas by various authors (e.g., Heinrich von Kleist, Robert Graves, Christa Wolf, and Marion Zimmer Bradley, among others). The Amazons can likewise be found in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians novels.

The myth of the Amazons was also the inspiration for DC Comics’ Wonder Woman series. The character of Wonder Woman, also known as Diana Prince, is an Amazon from the mythical land of Themiscyra who fights alongside other powerful superheroes, including Batman and Superman.

In film, the Amazons have been depicted in The Loves of Hercules (1960), War Goddess (1973), Amazons (1986), Deathstalker II (1987), and Hercules (2014), to mention just a few examples. They have made regular appearances in television, too, including Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (1995–1999), Young Hercules (1998–1999), Xena: Warrior Princess (1995–2001), and Supernatural (2005–2020).

The Amazons are also behind the various cinematic representations of Wonder Woman, including the recent DC Extended Universe films Wonder Woman (2017), Justice League (2017), and Wonder Woman 1984 (2020).

The Amazons have been featured in many role-playing and video games, including Diablo, Rome: Total War, Final Fantasy, Legend of Zelda, and Yu-Gi-Oh.

Finally, the Amazons have inspired the names of various landmarks, organizations, and, of course, military units composed of or led by females. Perhaps the most famous of these namesakes is Brazil’s Amazon River, which received its name after a female-led army of natives attacked a sixteenth-century European expedition sent to explore the area.