Theogony

The Fall of the Titans by Cornelis van Haarlem (1588–1560)

SMK (National Gallery Denmark)Public DomainTitle

The title of the Theogony (Greek Θεογονία, translit. Theogonia) translates to “birth of the gods.”

Pronunciation

English

Greek

Theogony Θεογονία (translit. Theogonia) Phonetic

IPA

[thee-OG-uh-nee] /θiˈɒg ə ni/

Author

Hesiod, the author of the Theogony, is one of the earliest known Greek poets. He belonged to the Archaic period of ancient Greek history (ca. 900–490 BCE), which saw important developments in technology, trade, the arts, and social life.

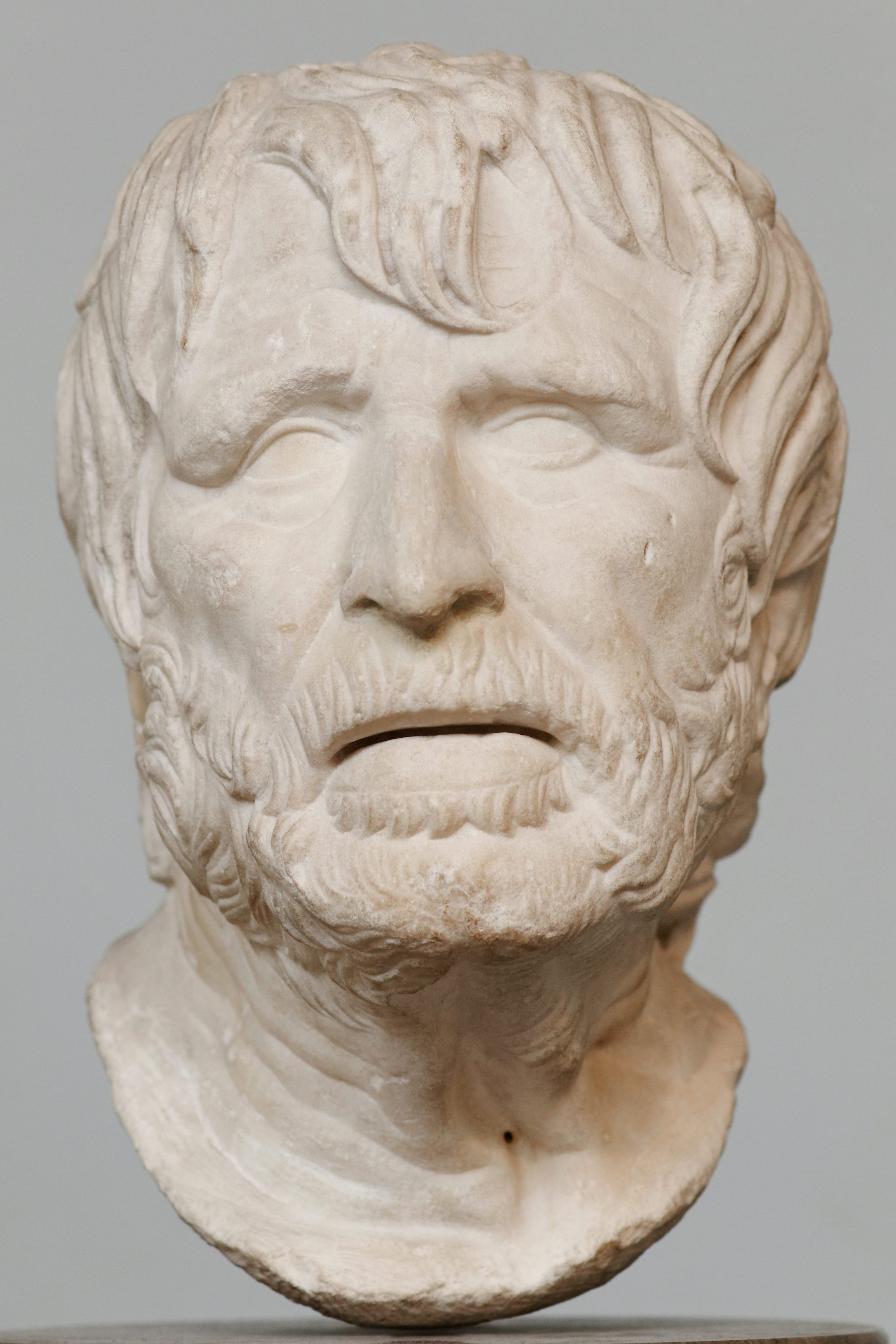

The so-called “Pseudo-Seneca,” now thought to be an imaginative portrait bust of Hesiod. Roman copy of Greek original from around the 2nd century BCE.

British Museum, London / Marie-Lan NguyenPublic DomainHesiod tells us a bit about his life in his own poetry—that he was the son of a poor tradesman and grew up in Ascra, a “miserable hamlet”[1] in Boeotia (in central Greece); that he was a shepherd until the Muses appeared to him one day and taught him to compose poetry;[2] that he once won a musical contest in Chalcis;[3] and that he had a brother named Perses who cheated him of his inheritance.[4] This sparse autobiography was later embellished, sometimes with rather unbelievable details.

Though debate continues over Hesiod’s life—who he was, when he lived, and whether a single “Hesiod” even existed—most scholars today agree that Hesiod lived around the end of the eighth century BCE and authored two works: the Theogony (in which Hesiod actually refers to himself by name) and the Works and Days. The many other poems attributed to Hesiod in antiquity—including the Shield of Heracles, the Catalogue of Women, and the Astronomy, among others—were most likely composed by someone else at a later period.

Mythological Context

The Theogony sets out to explain how the cosmos arrived at its present state. It stresses the anthropomorphism and brutality of the gods, even more so than Homer’s epics. In Hesiod’s account of the famous Succession Myth, for example, Cronus castrates Uranus and then swallows his own children before being defeated by Zeus. Xenophanes of Colophon, a philosopher who lived in the sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, wrote that:

Homer and Hesiod have ascribed to the gods all things that are a shame and a disgrace among mortals, stealings and adulteries and deceivings of one another.[5]

Certain religious aspects of the Theogony are somewhat unique to Hesiod. For example, the Theogony is curiously verbose in singing the praises of Hecate, a goddess usually associated with death and witchcraft.[6]

Yet the most important figure of the Theogony—the “hero” of sorts—is none other than Zeus. In both of Hesiod’s poems, Zeus serves as the embodiment of justice, symbolizing the present and final order of the cosmos. Where most of the other Hesiodic gods are savage and cruel, Zeus is astonishingly upright and all-knowing.

Attic red-figure amphora by the Berlin Painter (c. 480–470 BCE) showing Zeus wielding a thunderbolt and holding an eagle

Louvre Museum, Paris / Bibi Saint-PolPublic DomainIn the Theogony, Hesiod relates a number of interesting aetiological myths—that is, myths that explain the origins of a certain practice or aspect of the cosmos. For example, he tells a curious tale of how animal sacrifice originated when the Titan Prometheus attempted to trick Zeus.[7] But certain features of creation are conspicuously absent: most notably, the Theogony says nothing about where human beings came from.

The mythology of the Theogony also displays significant Eastern influences. This is hardly a surprise, as the text was written during a period of increased contact between the Greeks and the civilizations of the Near East. Even the alphabet in which the Theogony was written was adopted from the Phoenicians (the inhabitants of modern-day Lebanon).

In particular, Hesiod’s version of the Succession Myth bears a striking resemblance to Eastern texts such as the Enūma Eliš, a Babylonian creation epic, and the Hittite and Hurrian sagas of the exploits of the gods Kumarbi and Teshub. How and when these foreign traditions found their way to Greece is uncertain; perhaps they were filtered through the Phoenicians, from whom the Greeks learned their alphabet. In any case, parallels between these early Eastern works and Hesiod’s Theogony certainly have important implications for the development of Greek mythology.

Synopsis

In just over 1,000 verses, the Theogony records the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, from the first primordial deities to the Olympians. Interlaced with this genealogical catalogue (which contains some 300 names) is the Succession Myth—the story of how a succession of divine rulers culminated in the rise of Zeus and the current order of the cosmos.

Proem (1–115)

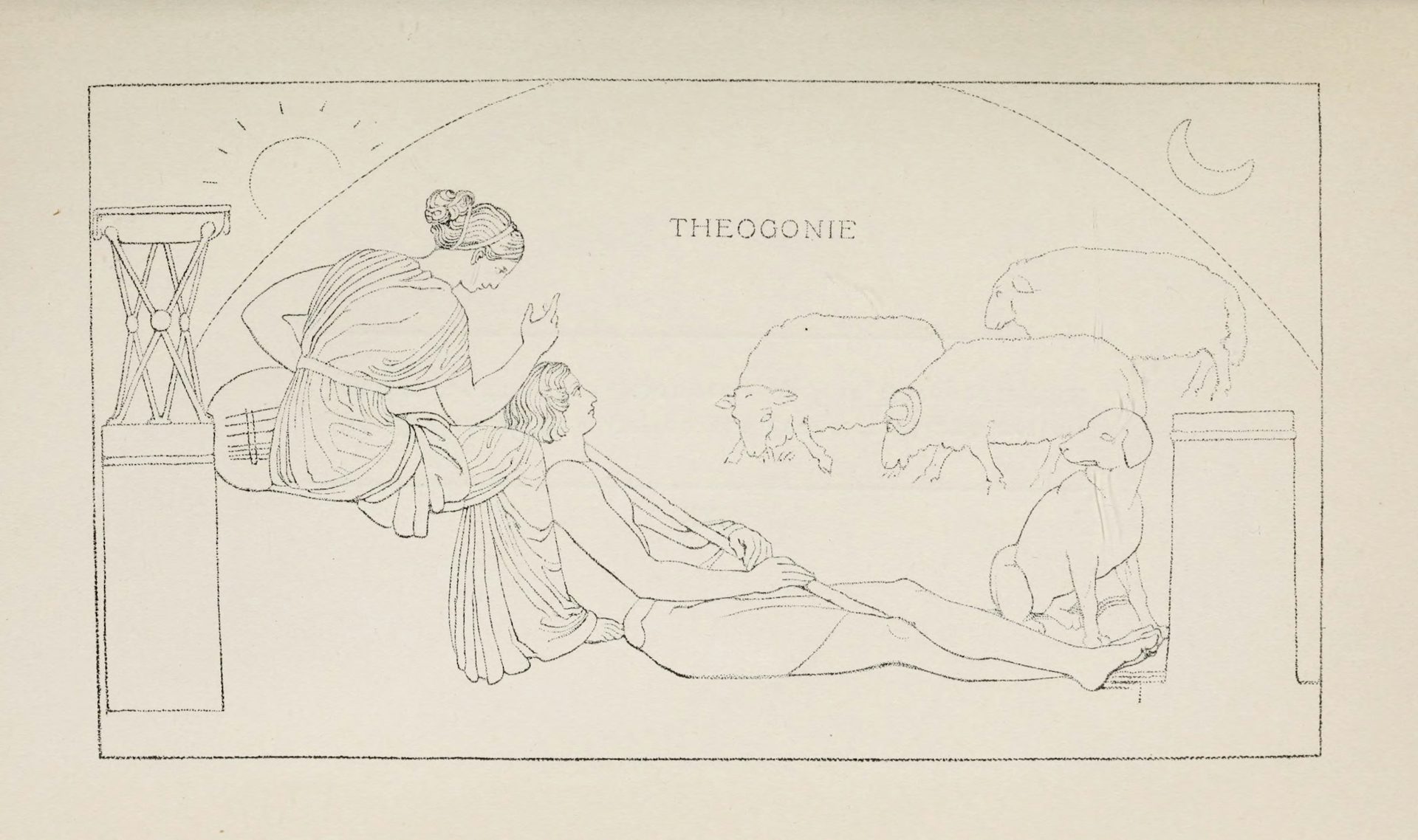

The Theogony begins with an introductory hymn or invocation (called a “proem”) addressed to the nine Muses. Hesiod describes his first encounter with the Muses on Mount Helicon and how they instructed him in the art of writing poetry (though not before reproaching him for his ignorance):

“Shepherds of the wilderness, wretched things of shame, mere bellies, we know how to speak many false things as though they were true; but we know, when we will, to utter true things.”[8]

Hesiod then states that his poem will deal with the origins and genealogies of the gods.

Illustration showing the Muse inspiring Hesiod to compose the Theogony by John Flaxman

John Flaxman's Zeichnungen zu Sagen des Klassischen Altertums (1910)Public DomainThe Origin of the Cosmos (116–22)

Next, Hesiod describes the three original primordial entities or gods: Chaos (best translated as “Chasm” rather than the English cognate “chaos”), Gaia (“Earth”), and Eros (“Passionate Love”).

The Offspring of the Primordial Gods (123–232)

Chaos and Gaia give rise to two separate genealogical lines. Chaos begets Erebus (“Darkness”) and Nyx (“Night”), who together become the parents of various deities and personifications, including Hemera (“Day”) and Aether (“Upper Air”). Gaia, meanwhile, begets Uranus (“Sky”), and together they have the Hecatoncheires (“Hundred-Handers”), the Cyclopes, and the original twelve Titans. Cronus, the youngest of the Titans, castrates Uranus, and from his severed genitalia are born Aphrodite and several other deities.

The Birth of Venus by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1879)

Musée d’Orsay, ParisPublic DomainThe Descendants of Pontus (233–336)

Pontus (“Sea”), one of Gaia’s children, begets Nereus, who fathers the beautiful Nereids. Pontus also begets Phorcys and Ceto, whose monstrous brood includes the Gorgons, the Graiae, and Echidna.

The Offspring of the Titans (337–616)

The Titans, most of whom marry one of their siblings, have many important children, including the Oceanids and the Potamoi (children of Oceanus and Tethys); Hecate (daughter of Asteria and Perses); the Olympians (children of Cronus and Rhea); and Prometheus (son of Iapetus). Cronus swallows all the Olympians except the youngest, Zeus, who is destined to overthrow him. Prometheus, meanwhile, plays an important role in the origins of animal sacrifice, fire, and women.

The Titanomachy (617–720)

With the help of the Hecatoncheires, the Cyclopes, and his recently regurgitated siblings, Zeus defeats the Titans and casts them into Tartarus.

Tartarus (721–819)

Tartarus, a grim subterranean pit, is described at length, as are its inhabitants (the Titans, the Hecatoncheires, Hades, Hecate, etc.).

Typhoeus (820–80)

Zeus battles and defeats the monstrous Typhoeus, the last of Gaia’s offspring.

The Offspring of the Olympians (881–962)

Through their various marriages and affairs, the original Olympians beget a second generation of gods, including Athena, the Muses, Apollo, Artemis, Hephaestus, Hermes, Dionysus, and Heracles.

The Offspring of the Goddesses (963–1022)

Hesiod bids farewell to the Olympians and gives a catalogue of the children of goddesses who slept with mortal men. The end of the poem (which is likely inauthentic) transitions to a separate catalogue of all the heroic children born to mortal women (presumably a reference to the fragmentary Catalogue of Women, another poem traditionally attributed to Hesiod).

Style and Composition

Scholars believe the Theogony was probably composed before the Works and Days, the other epic attributed to Hesiod. The Theogony is considered more linguistically and stylistically crude, suggesting that the Works and Days represents the work of a more mature poet—not to mention the fact that the Works and Days makes at least one clear allusion to the Theogony.[9]

Hesiod’s Theogony, like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, adheres to the basic conventions of early Greek epic poetry, employing dactylic hexameter and an elevated and artificial linguistic diction, which does not appear to have corresponded to any spoken dialect of ancient Greek.

Hesiod’s poems, like those of Homer, represent one of the earliest Greek forays into a new literate style of poetic composition that took advantage of the introduction of writing (imported from Phoenicia during Hesiod’s time). While Hesiod’s poetry retains some of the formulaic elements that distinguished earlier, purely oral poetry, his works are remarkable in that they were some of the first to be written down.

Themes

At its core, the Theogony is a poem about theogony (the origins of the gods) as well as cosmogony (the origins of the universe). The poem’s violent cycle of divine births, usurpations, and successions explores themes such as order and chaos, power, and divinity.

There is a certain religious fervor underlying the Theogony, especially surrounding gods such as Zeus and (somewhat idiosyncratically) Hecate. The gods—and Zeus specifically—serve as symbols of the justice and order of the cosmos. Within that world, the lowly human’s role is simply to obey.

Perhaps because it represents the transition from an oral culture to a literate one, the Theogony often strikes modern readers as stylistically strange and tedious. Much of the Theogony is devoted to cataloguing gods and genealogies: in total, the poem names some 300 gods. At times, the Theogony can be repetitive, rambling, or hopelessly ambiguous.

For all his flaws, Hesiod is extremely valuable to scholars because he actually names himself in his poems and even reveals some details about his life (however fanciful some of these may be). Homer, Hesiod’s slightly earlier rival, did no such thing. Hesiod thus stands out as the first true “author” in Western literature, setting himself apart from earlier oral poets and situating himself even more firmly in the emerging literate culture.

Reception

Antiquity

Over time, the Theogony became much more than just a genealogical outline of Greek mythology. It was regarded as a key text by the entire Greek world, a “Panhellenic” poem rather than a text of only local importance. The ancient Greeks regarded it as one of their foundational works of literature and religion. According to the historian Herodotus, it was Hesiod and Homer “who taught the Greeks the descent of the gods, and gave the gods their names, and determined their spheres and functions, and described their outward forms.”[10]

Hesiod’s works were foundational not only for the Greeks but also the Romans. Every ancient poet—from those, like Archilochus, who lived just after Hesiod, to imperial Roman poets like Virgil, Ovid, and Statius—can be said to have been impacted by Hesiod in some way. Hesiod’s cosmogony even influenced the cosmologies of early Greek philosophers such as Thales, Anaximander, and Anaxagoras.

Medieval, Renaissance, and Early Modern Europe

Hesiod’s popularity waned as late antiquity transitioned into the European Middle Ages. Though the Works and Days was still sometimes admired for its ethic of hard work and honesty, the Theogony, full of pagan gods and their myths, had little to offer the Christian successors of the Roman Empire.

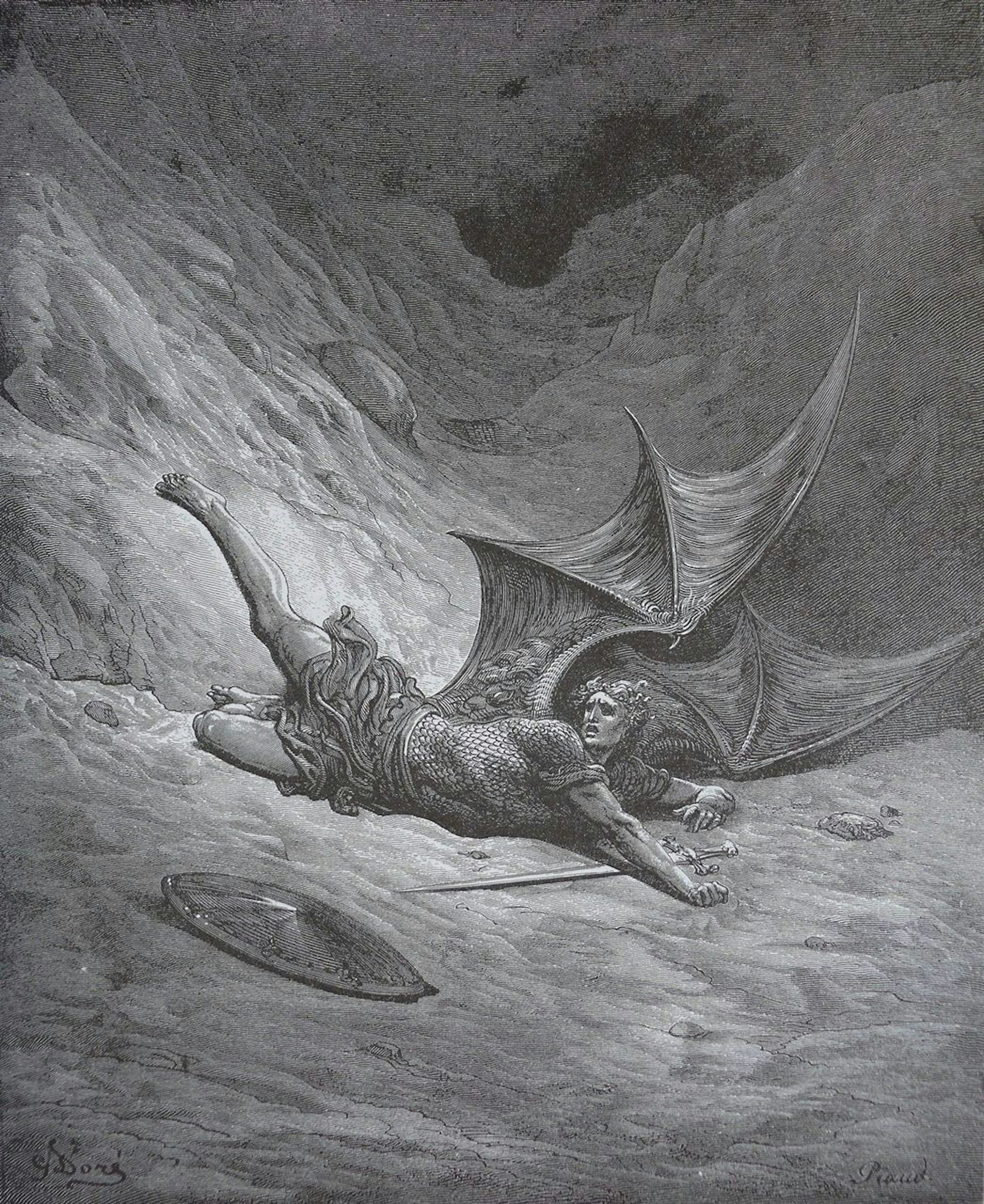

Starting in the Renaissance, however, there was some renewed interest in Hesiod and his Theogony, with literary figures such as Petrarch and Erasmus vaunting the text’s importance. Scenes from the Theogony inspired great works of art, such as Sandro Botticelli’s famous painting The Birth of Venus (created in the fifteenth century). Later, the Theogony exerted an important (though somewhat underappreciated) influence on John Milton’s Paradise Lost (originally published in 1667), which is often quite Hesiodic in its vivid depiction of the divine powers governing the cosmos and human life.[11]

Illustration for John Milton's Paradise Lost by Gustave Doré (1866)

Wikimedia CommonsPublic DomainPop Culture

Today, Hesiod is not as familiar in modern pop culture as Homer. However, any new adaptation of Greek mythology—literary, cinematic, or otherwise—will inevitably owe something to the descriptions of the gods and their genealogies as laid out in Hesiod’s Theogony.

Translations

There have been numerous translations of Hesiod’s Theogony (usually grouped together with his Works and Days). The following is a selected chronological list of important and useful translations:

Evelyn-White, H. G., trans. Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914: A rather old-fashioned prose translation. Can be found in the public domain and thus remains an accessible option.

Lattimore, Richmond, trans. Hesiod: The Works and Days, Theogony, The Shield of Herakles. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959: Old but still highly-regarded translation in non-metrical, non-rhyming verse.

Wender, Dorothea, trans. Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days; Theognis: Elegies. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973: Readable verse translation, complete with brief commentary. The volume includes a translation of the poetry of Theognis.

Athanassakis, Apostolos N., trans. Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Shield. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983: Readable free verse translation with commentary.

Frazer, R. M., trans. The Poems of Hesiod. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983: Readable and accurate verse translation with commentary.

West, Martin L., trans. Hesiod: Theogony and Works and Days. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988: Prose translation that is very true to the original, produced by one of the most important scholars of Archaic Greek literature. Includes commentary.

Lombardo, Stanley, trans. Works and Days and Theogony. Hackett Classics. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993: Lively, rather folksy verse translation with added commentary.

Hine, Daryl, trans. Works of Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005: Readable, accurate, and annotated translation replicating the verse of the original (dactylic hexameter). Includes a translation of the Homeric Hymns.

Most, Glenn, trans. Hesiod, Vol. 1: Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia. Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006: A very accurate, readable new prose translation, replacing Evelyn-White’s older translation in the Loeb Classical Library series.

Schlegel, Catherine, and Henry Weinfield, trans. Theogony and Works and Days. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006: Unique translation employing rhyming iambic heptameter couplets. Flows well but is not always faithful to the original. Includes commentary.

Johnson, Kimberly, trans. Theogony and Works and Days: A New Critical Edition. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2017: Musical verse translation in bilingual edition that carefully seeks to preserve the structure of the original. Includes commentary.

Powell, Barry, trans. The Poems of Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, and the Shield of Heracles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017: Accessible verse translation, complete with helpful annotations.