Anubis

Overview

One of the most famous figures of the Ancient Egyptian pantheon, Anubis was a powerful deity whose role shifted over time. Before Osiris and Isis rose to prominence, Anubis was worshipped as the god of the dead. When Osiris took on this role, however, Anubis became the god of mummification (as well as Osiris’s bastard son).

Seen here in his traditional form, this Anubis statuette (332–30 BCE) greets the recently deceased to the underworld.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainDespite his significance and multi-millennia long worship, Anubis was seldom a main character in the Egyptian mythos. He was an integral part of the story of Osiris’s murder, in which he embalmed the deceased god. Thereafter, he was known as the Lord of the Mummy Wrapping.

Etymology

Like much of the Egyptian pantheon, Anubis’s name came to us as a Greek translation of his Egyptian name. This was partly because the Greeks continued to worship or at least admire the Egyptian gods, but also due to the ambiguity of the vowelless writing system employed in Ancient Egyptians. An accurate, albeit unhelpful, rendering of his name in Ancient Egyptian is jnpw.[1] Some translations of jnpw have rendered Anubis’s Egyptian name as “Anpu” or “Inpu.”

Anubis had many epithets, including:

The First of the Westerners[2]

Lord of the Mummy Wrapping[3]

Chief of the Western Highland (the land of the dead was thought to be in the west, where the sun set)[4]

Counter of Hearts[5]

Chief of the Necropolis[6]

Prince of the Court of Justice[7]

Master of Secrets

The One Who Eats His Father

The Dog Who Swallows Millions

Attributes

One of the most iconic Egyptian deities, Anubis possessed several distinctive features. While he had a human body (like most Egyptian gods), he also had a jackal’s head and tail. He was typically all black, and was often portrayed in a seated position.[8] Like many Egyptian gods, Anubis was capable of shapeshifting; he was so shocked at the sight of Osiris’s dead body that he immediately turned into a lizard.

Anubis enacting the mummification ritual, as depicted in the tomb of the artisan Sennedjem at Deir el-Medina. Pharaohs did not hold a monopoly of mummification—wealthy individuals like Sennedjem could and did comission elaborate tombs with paintings like this adorning the walls.

Gabriel IndurskisCC BY-NC-SA 2.0Anubis was a faithful follower of Isis, who adopted him following his abandonedment as an infant. A fierce fighter, he routinely defeating the god Set in battle.

Family

As one of the oldest gods in the Egyptian pantheon, Anubis had a varied and somewhat inconsistent mythology. Initially, Anubis was a son of Ra who served as the primary god of the dead. As time went on and the cult of Osiris grew in power, Anubis’s stories were incorporated into this new, larger mythos.[9]

By 2000BCE, Anubis had become a bastard child of Nephthys and Osiris. In this new version of Anubis’s origins, Nephthys abandoned Anubis for fear that her husband Set would discover her infidelity. Isis later found the abandoned child and adopted him.

In several alternative mythologies, Anubis was said to be the son of either Bastet or Set.[10]

In “The Tale of Two Brothers,” Anubis had a younger brother named Bata. An ancient regional deity, Bata would ultimately not survive the passage of time or the vagaries of religious change.[11]

In myths that place him as the son of Osiris, Anubis had several brothers, including Horus, Babi, Sopdet, and Wepwawet.[12]

Family Tree

Mythology

Anubis’s origin and role as god of the dead were directly linked to his depiction as a jackal or jackal-headed man. Jackals were scavengers who would frequent burial sites and uncover shallow graves. The Egyptians may have enshrined the jackal’s behavior in order to make it seem benevolent.[13] Alternatively, Anubis worship may have developed as a means to exercise supernatural control over jackals. If Anubis was worshipped properly, the jackals might not disturb the venerated dead.[14]

This wooden statue (664-30 BCE) shows Anubis poised and ready to defend a burial site. In this role, Anubis closely resembles a full-bodied jackal.

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0Early on in Egyptian history, Anubis was worshiped as a god of the dead. After Osiris rose to prominence, Anubis’s role changed. He became a god of embalming and psychopomp who escorted the dead on their journey to the afterlife.[15]

In the post-Late Period (664-30BCE) era, Anubis became associated with necromancers. Demotic (a written language that superseded hieroglyphs) spells would invoke Anubis, who would then act as an intermediary, fetching spirits or gods from the underworld.[16]

Origin Myth

The most famous version of Anubis’s origin came to us from the Greek historian Plutarch (46-120CE). Following Osiris’s murder at the hands of his brother Set, Isis set out in search of his body. It was during this search that she learned her sister Nephthys had born a child with Osiris.

Fearing that her husband, Set, would discover her infidelity, Nephthys abandoned the newborn child. Isis, known for her maternal benevolence, found the child and adopted him. She named the child Anubis, and he thereafter serverd as her loyal protector.[17]

Anubis and the Mummification of Osiris

Following his murder, Osiris’s body was ultimately destroyed. Whether or not it was chopped into pieces—as Plutarch and other Greek historians suggest—or simply subject to natural decomposition is irrelevant.[18] What is significant, however, is that after Osiris’s body was recovered, it was embalmed. The cultural practice of mummification was derived from this first embalming, and was intended to emulate Osiris’s journey to the afterlife.

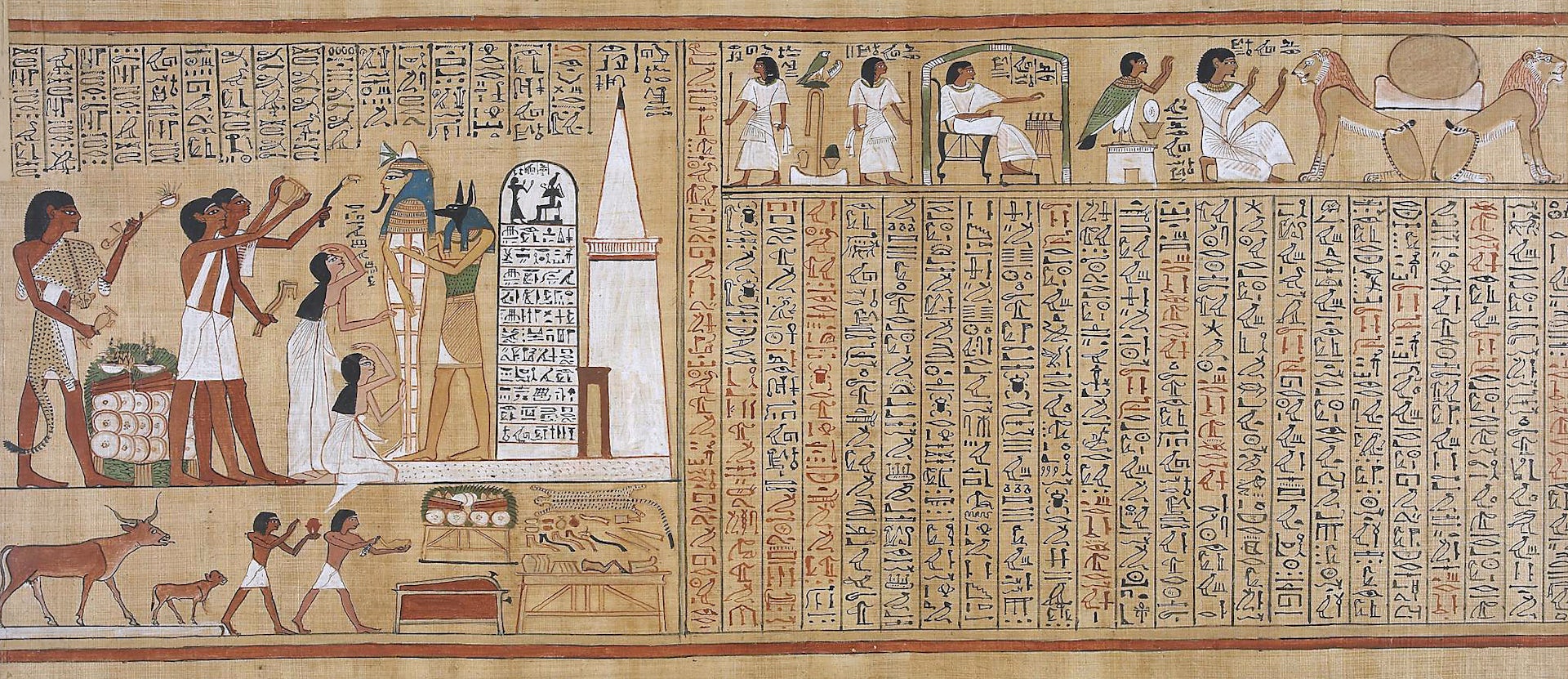

This page from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer (c. 1450 BCE) depicts the Opening of the Mouth ceremony (left).

The Trustees of the British MuseumCC BY-NC-SA 4.0After Isis had recovered her husband’s body, the sun god Ra asked Anubis to assist with the embalming process.[19] With some assistance from Horus and Thoth, he wrapped the body in cloth and completed what would become known as the Opening of the Mouth ritual. This rite was meant to ensure that the mummified person’s senses would continue to work in the afterlife.[20]

Anubis’s Battles with Set

While Set had succeeded in killing Osiris, he still needed to destroy his brother’s body in order to defeat him completely. After Osiris’s body was recovered by Isis, Set plotted to steal it back and complete its destruction.

During the embalming process, Osiris’s body was kept in the wabet, or place of embalming. Noting that Anubis left the wabet every night, Set devised a plan. Transforming himself into Anubis, he strolled past the unsuspecting guards and stole Osiris’s body.[21]

Set would not able to make it far, however, before Anubis discovered the theft and set out in pursuit. In an attempt to ward off his pursuer, Set turned himself into a bull. The jackal-god was not intimidated, however. Upon capturing Set, Anubis castrated him and imprisoned him in Saka, the 17th nome of Egypt.[22]

Not one to be deterred, Set escaped his imprisonment and continued his mission. This time, Set attempted to steal his brother’s body in the form of a great cat. The plan failed, and Anubis caught him once more; the jackal-headed god punished Set by branding him with hot irons. This myth thus explained how leopards became spotted.

Ever persistent, Set continued trying to steal Osiris’s body back. Again, he turned himself into Anubis, and again he was caught. Set was forced to serve as Osiris’s throne for all eternity—that is, until he escaped.

Set’s next attempt would be his last. After catching Set yet again, Anubis killed him, flaying his skin and setting his body aflame. After donning the flayed skin, Anubis snuck into Set’s camp and decapitated his entire army with a single slash of his sword.[23] Set’s army was killed in the 18th nome, where a reddish mineral makes the land appear stained with blood.[24]

The Tale of Two Brothers

This myth is a little different as it fits outside of the Osiris-centric mythological canon. Instead of the normal cast of Egyptian gods and goddesses, the ancient god Bata starred alongside Anubis.

Anubis’s younger brother Bata worked on his brother’s farm. One day, while doing chores for his brother, Bata ran into Anubis’s wife. She was quite taken with what she saw, and invited Bata to bed with her. Shocked at this invitation, Bata told her “you have been to me as a mother and what you say is an abomination!”[25] He promised he would tell no one of the incident so long as she never spoke of this again.

Anubis’s wife, however, had other plans. When Anubis came home, she pretended that Bata had beaten her, saying that he had propositioned her and struck her when she declined.

Now enraged, Anubis attempted to kill his brother. Try as he might, however, he could not harm Bata; divine intervention prevented Anubis from taking his revenge. The next day, Bata told Anubis his side of the story. He then demonstrated his conviction by cutting off his penis and throwing it into the river, where it was eaten by fish. Having done this, Bata told Anubis he was leaving for the Valley of Cedars, saying:

There I will take out my heart and place it high in The cedar on a flower. If the tree is cut down, I will Appear to die, but if you spend seven years seeking The tree and find it and place my heart like a seed In water, I will live again. You will know you are Needed when you find your pot of beer in a froth.

Bata arrived in the valley and lived alone there for some time. Sympathetic to his loneliness, Ra-Herakhty had the god Khnum make Bata a wife on his potter’s wheel. Bata and his wife were happy for a time, but this happiness would not last. The Seven Hathors soon came to Bata and warned him that his wife was fated to have an unhappy end.

Bata loved his wife dearly and told her to take great care since he knew of her prophesied fate. He also told her about his heart at the top of the cedar, and how if the tree was cut down he would die.

One day while walking along the beach, the sea tried to catch Bata’s wife. She managed to flee, but the sea snatched away a lock of her hair. Eventually, this lock of hair made its way to the king of Egypt, who was enchanted by its lovely aroma. His advisors determined the hair had come from Ra-Herakhty’s daughter, and sent out search parties to discover her whereabouts.

When the king found her, Bata’s wife told him the secret of her husband’s heart. She also explained that Bata would die if the tree was cut down. Wanting her for himself, the king had Bata’s tree cut down, causing Bata to appear to die. At the same instant, Anubis noticed his pot of beer frothing, and knew that it was time for him to seek his brother. While he found his brother’s body, Anubis was deeply saddened that he could not find his heart. Before he returned home, Anubis decided to take a cedar berry as a momento. Unbeknownst to him, this berry was actually Bata’s heart.

When Anubis returned home, he put the cedar berry in a cup of water. The berry did not sprout as a normal seed would, but instead revived Bata’s body (which Anubis had also brought home for burial). Upon drinking the seed, Bata made a full recovery.[26]

In the interim, Bata’s former wife had married the king. In an elaborate scheme, Bata turned himself into a bull which Anubis presented as a gift to the king. Through a series of transformations, Bata became a splinter that the queen (his former wife) eventually birthed into a baby boy. Eventually the king died and the prince (Bata) took power. At this point, Bata testified against his mother/wife, who was disgraced. Bata appointed Anubis as his crown prince. When Bata died many years later, Anubis succeeded him as king.[27]

Popular Culture

Anubis is perhaps one of the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and has been featured in movies, books, TV shows, video games, and music:

In Neil Gaiman’s book American Gods, Anubis appeared as a character named Mr. Jacquel.

The electro-avantgarde band Los Iniciados’ first album was entitled “La Marca de Anubis.” The cover art for the album showed Anubis performing the “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony upon a prone, mummified figure—possibly Osiris.

While the Nickelodeon mystery TV series House of Anubis (based on the Belgian/Dutch show Het Huis Anubis) did not include Anubis as a character, it did include several references to Egyptian mythology. In the show, the “Mark of Anubis” was a curse that would cause those bearing the mark to die. This harkened back to Anubis’s classic role as the enforcer of curses.[27]

The ancient Greeks believed that Anubis was connected to their god Hermes. This ancient Roman statue at the Vatican Museums depicts a hybrid of the two deities: Hermanubis.

Carole RaddatoCC BY-SA 2.0In Ancient Greece, the phrase “by the dog” was used to refer to Anubis, and was invoked as a means of guaranteeing the truth of a statement. similar to how we might now say “I swear on my mother’s grave” or “I swear to god.” Plato was fond of having Socrates invoke the phrase, and used it several times throughout his works.[29]