Isis

Overview

One of the best-known goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon, Isis was the granddaughter of Ra, wife of Osiris, and mother of Horus. While she was best known as a powerful sorceress and healer, she was also a fiercely protective mother and loyal wife. Her acts of healing and compassion were renowned throughout the land; those who threatened her loved ones, however, did so at their own peril.

Etymology

The etymology of the Egyptian gods’ names have largely been lost to time and translation. Nevertheless, some information relating to Isis’s etymology has been discovered. Isis was generally depicted wearing a crown resembling the hieroglyph for “throne.” Her name—as written in Ancient Egyptian—incorporated this glyph as well. Thus, Isis’s name was commonly understood to mean “throne goddess.”[1]

This statuette of Isis (611–594 BCE) once nursed a baby Horus figure (now missing). Her headdress of cow horns and a solar disk is in line with common depictions of the goddess in Late Period Egypt. This headdress was also associated with the goddess Hathor, whose mythology often coverged with that of Isis.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainAttributes

Isis was a goddess of contradictions. While she could be bloodthirsty and ruthless, she was also compassionate and loyal. She was known for her acts of healing, but her grief could also cause the death of innocents. Isis happily extorted her grandfather Ra so that her unborn son Horus could lay claim to the throne. Later, when Horus was engaged in a competition with his uncle Set, Isis cheated on her son’s behalf. On yet another occasion, she released a captured Set out of familial obligation.

She was an immensely powerful sorceress known for her wondrous healing spells.

Isis was usually depicted in human form, and could sometimes be seen carrying a sistrum (an ancient percussion instrument). The myths and imagery surrounding Isis and another goddess, Hathor, were sometimes conflated. Isis would, at times, bear the cow horns and solar disk more commonly associated with Hathor.[2]

In this ancient Roman statue, Isis holds a sistrum, or rattle-like percussion instrument, in her right hand.

Marie-Lan Nguyen CC0Family

Isis was the fourth child born to the gods Nut and Geb. Her older siblings included Osiris, Horus the Elder[3] and Set; she also had a younger sister named Nephthys.

Isis conceived her son, Horus the Younger, with her deceased brother/husband Osiris. Isis’s relationship with Osiris was somewhat peculiar: the two began their relationship in the womb and thus were born as husband and wife.[4]

She raised Anubis, the bastard child of Osiris and Nephthys, as her own after his mother abandoned him.

Family Tree

Mythology

Isis was an extremely complex goddess, which may explain the longevity of her cult.

While other Egyptian gods were replaced or discarded, Isis continued to be worshipped long into the Greek and Roman periods. For a time, the prevailing thought in Greco-Roman culture was that Isis had created the world, and that all of the other gods were simply alternative names for Isis.[5] Isis’s cult remains active to this day, as the goddess has become a part of modern paganism.

Extorting the Sun: Isis Poisons Ra

In Egyptian mythology, knowing someone’s name was thought to give you power over them. Accordingly, true names were closely guarded secrets. Ra’s true name was immensely powerful, as whomever had access to it could control the sun god and all his might.

Isis had begun plotting her son’s ascent to the throne well before he was born. Such a plot required great cunning and ingenuity, for though Isis was a sorceress of great power, even her magic could not harm the mighty Ra. For all his power, Ra did have several weaknesses. He was elderly, and tended to drool. Isis collected some of this spittle and mixed it with clay, forming it into the shape of a cobra. Then, using her magic, she animated the cobra and set it along a path that Ra walked daily.[6]

True to form, Ra walked the path the next day, and the cobra struck. Unable to resist the cobra’s venom, which had been made from his own essence, Ra became wracked with pain and fever. As he suffered, Isis approached him and offered to cure him—on the condition that he tell her his true name.

Though he was now delirious with pain, Ra was no fool. He rattled off a list of names he was known by, but did not reveal his true name. Isis knew that she had not yet received his true name and told him again, she could only heal him if he gave her his true name.

Ra’s pain had intensified throughout this process, and he knew that he would have no peace until he was cured. In an effort to avoid giving her any power over him, Ra attempted to bargain with Isis. In his weakened state, however, he bargained poorly. Isis and Ra ultimately agreed that, if Isis cured him, he would give her as-of-yet unborn son his eyes (here meaning the sun and the moon, the sources of Ra’s power).

True to her word Isis offered up an incantation to relieve Ra of his suffering:

Break out, scorpions! Leave Re! Eye of Horus, leave the god! Flame of the mouth – I am the one who made you, I am The one who sent you – come to the earth, powerful poison! See, the great god has given his name away. Re shall live, Once the poison has died

This laid the foundation for unborn Horus to one day become king of the gods, and a sun god in his own right. This was far in the future, however, and both Isis and Horus would face many trials before these events would come to pass.

Built around 280 BCE, the walls of the Temple of Isis at Philae bear scenes from Isis's storied mythology.

markgoddard / iStockThe Murder of Osiris

One of the best-preserved tales from Egyptian mythology was the murder of Osiris and Isis’s ensuing quest to retrieve his body.

The story began during a period of prosperity and peace. Osiris ruled over Egypt and introduced its citizens to agriculture; he also eliminated barbarism. After civilizing Egypt, Osiris embarked on an expedition to bring culture to the rest of the region, which ranged from India to Ethiopia.[8] During Osiris’s absence, Isis ruled over Egypt. With Thoth as her advisor, she proved to be a successful queen.[9]

Set was jealous of his brother’s success, and plotted to kill him when he returned from his travels.[10] He held a party in honor of Osiris’s return, and during the festivities tricked his brother into lying in an ornate box. Set then sealed the box with molten lead and cast it into the Nile.[11]

Isis’s Search for Osiris

Isis, who was in a distant town at the time of the murder, instantly knew of her husband’s death. Without moving from where she stood, she cut off a lock of her hair and donned mourning robes.[12] Isis then set out in search of her husband’s body. Eventually, she came across some children playing who told her that they had seen a chest floating north on the Nile.[13]

During her quest, Isis discovered that her sister Nephthys had once seduced Osiris. After giving birth to Osiris’s child, Nephthys had abandoned it for fear of her husband’s wrath. Concerned, Isis searched for the boy and ultimately found him being cared for by wild dogs. She adopted him then and there, naming him Anubis.[14]

Upon resuming her search, Isis learned that Osiris’s body had washed ashore at a place called Byblos. While Byblos’ true location has been lost to vagaries of time, it appears to have been a papyrus swamp in Syria or Northern Egypt.

The passage of time in myths like these is often difficult to discern. Either a significant amount of time had elapsed while Isis was trying to locate the body, or Osiris’s body had magical properties. Whichever the case, a great tamarisk tree had grown around Osiris’s sarcophagus.[15]

The tree became known far and wide for its thick trunk and beautiful flowers. It became so well known, in fact, that the local rulers, King Malkander and Queen Athenais, determined it to be the perfect pillar for their new palace and had the tree cut down. Unbeknownst to them, the section they had chosen to use for their pillar contained the body of Osiris.[16]

Isis arrived too late to find her husband, and recognized that she had lost him once again. She sat in mute despondency long enough to draw the attention of a pair of Queen Athenais’ handmaids. The handmaids struck up a conversation with the depressed goddess, and became perfumed by their proximity to her.

Upon returning to the palace, the handmaids were questioned as to their heavenly scent; they proceeded to tell the queen of their meeting with Isis. Intrigued, the queen set off to meet Isis in person. The two women became friends almost immediately, and the queen invited Isis to be her youngest child’s nurse. Isis accepted the invitation, and, upon learning that the child suffered from an incurable illness, offered to heal him. She offered this service on one condition—she must be able to work in secret.[17]

Depending on the version of the legend, the queen either accidentally stumbled upon Isis working her magic to heal her son, or intentionally hid herself in Isis’s chambers in order to discover her methods. Upon being discovered, Isis revealed herself to be a goddess.

Here, the stories diverge again: in some versions, Isis demanded to be given the pillar. In others, the queen offered Isis anything she would like as a gift. In both cases, Isis gained access to the pillar and recovered Osiris’s body. Isis’s grief at seeing her deceased husband’s body was so great that the child she was healing died of fright (other stories held that it was the child’s brother).

The Conception of Horus

Having finally recovered Osiris’s body, Isis set about attempting to revive him. Multiple versions of this tale exist, with each offering different interpretations as to how and when Osiris was resurrected.

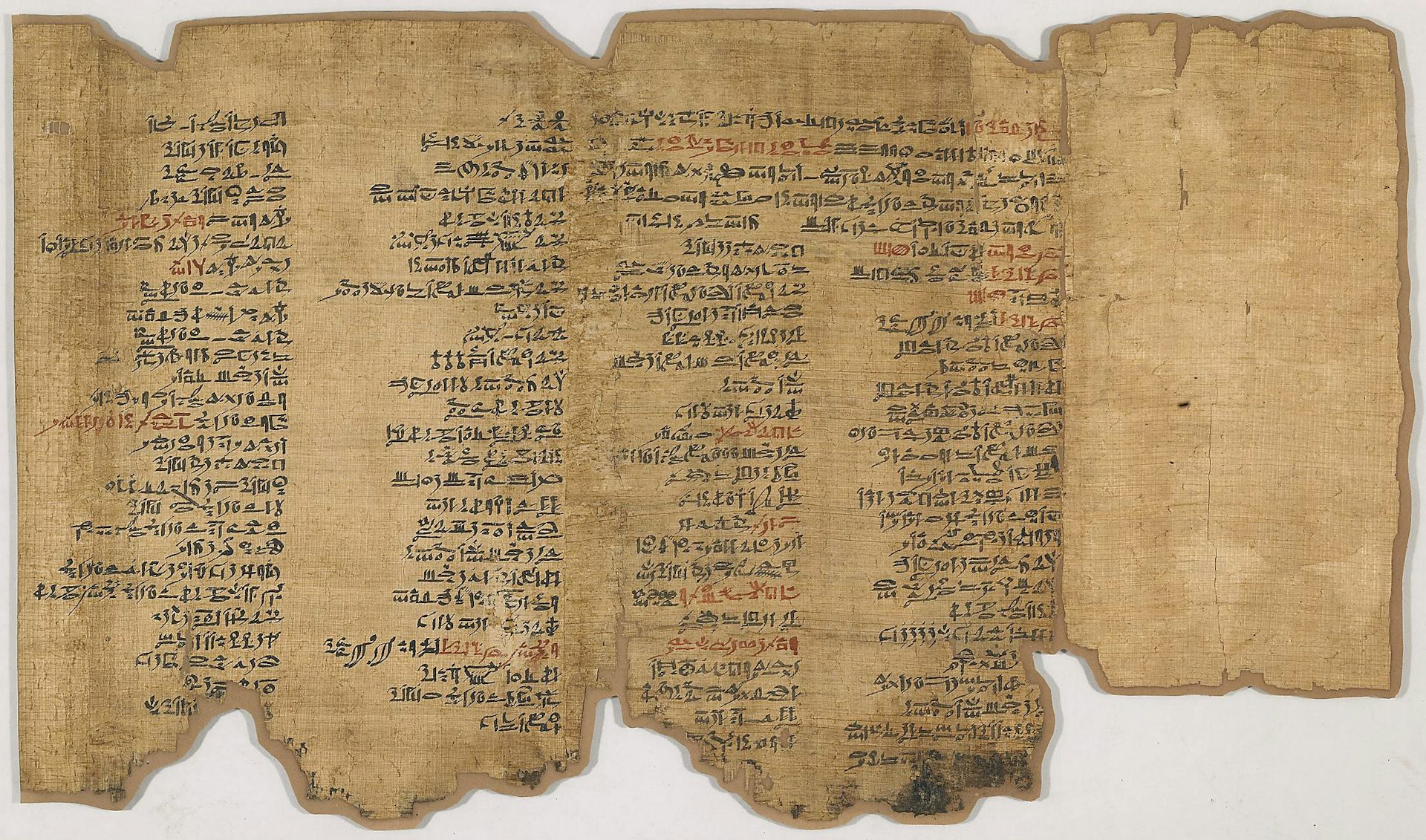

The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus (305 BCE) provides a unique interpretation of the myth of Horus's conception. It essentially served as a script for religious reenactments of the myth.

The Trustees of the British MuseumCC BY-SA 4.0The most commonly told version of this tale comes to us from the Greek historian Plutarch (46-120BCE). While Plutarch’s version is widely known, he wrote his account over a thousand years after the myth had fully developed. As such, his version often differed from those few surviving fragments in the ancient Egyptian record.

In Plutarch’s telling of the story, Isis recovered Osiris’s body only to have Set manage to accidentally discover its whereabouts. Set dismembered the freshly recovered body and scattered it across the land. Isis was able to locate all of Osiris’s body parts, with the exception of his penis.[18] When she put his body back together, Isis replaced his phallus with a waxen copy. Egyptian sources often omitted any mention of dismemberment; these sources held that Osiris’s bodily degradation was the result of natural decomposition.[19]

In an alternative version of the story, Isis and Nephthys worked together to revive Osiris. Their efforts were successful, if short-lived. Osiris returned long enough to impregnate Isis, but departed the land of the living shortly afterward.[20]

According to a tradition from the Temple of Hathor at Dendera, Isis stood to the right of Osiris’s body and Thoth stood to his left. Together, they put their hands upon him and engaged in a ceremony known as ‘the opening of the mouth.’ This ritual was an important step in the mummification ceremonial rites and was believed to awaken the dead for their journey to the afterlife.[21]

In another version, Isis took the form of a kite (a bird of prey):[22]

She made light [to come forth] from her feathers, she made air to come into being by means of her two wings, and she cried out the death cries for her brother. She made to rise up the helpless members of him whose heart was at rest, she drew from him his essence, and she made therefrom an heir.[23]

Fearing that Set would try to destroy her unborn child, Isis petitioned the gods for their protection. Atum asked her how she could know of the child’s divinity; she replied that she was Isis and her child was conceived from Osiris’s seed. Atum was convinced, and decreed that Set could not harm her unborn child. To ensure this godly restraining order, Atum arranged for the snake goddess Werethekau to protect the pregnant Isis.[24]

This relief at the temple of Seti I in Abydos features Isis (in kite form) conceiving Horus with the body of Osiris.

Olaf TauschCC BY 3.0The Birth of Horus

After Osiris’s death, Set took control as pharaoh. Undeterred by Atum’s promise of protection, Set imprisoned Isis and her sister Nephthys in the spinning house of Sais.

Some versions held that while Isis was imprisoned in the spinning house, Nephthys (Set’s wife) was merely confined to her house. After Nephthys eventually escaped, she helped Isis break out of the spinning house.

Having escaped Set’s grasp, Isis set out for the floating island of Pe, where the goddess Wadjet (also known as Uazet or Wadjyt) resided. Upon arriving at this safe haven, Isis cut the island’s moorings and set it adrift.

The Greek historian Herodotus (circa 484-425BCE) not only knew of this legend, but reportedly visited the island as well. Despite his willingness to present fantastical representations, Herodotus downplayed the island’s mythical properties, writing: “the Egyptians affirm it to be a floating island: I did not witness the fact, and was astonished to hear that such a thing existed.”[25]

Horus’ birth was challenging for Isis, who labored painfully for many hours. Eventually, a pair of gods appeared and anointed her head with a dab of blood, allowing Horus to be born at last. The son of Isis and Osiris was born on the vernal equinox—better known as the first day of spring.[26]

Hearing of Horus’ birth, Set immediately embarked on an expedition to destroy him. With assistance from Nephthys, Wadjet, Nekhbet, and Hathor, Isis raised Horus in the papyrus swamps of Northern Egypt. Whenever Isis sensed Set’s approach, the group would move on before his followers could find them.

On one occasion, Set nearly caught Isis. She was saved by Horus of Behdet,[27] who engaged Set in a great river battle and allowed her entourage to flee.[28]

Isis and the Seven Scorpions

As is common in Egyptian mythology, no single version of a story was canon. Another version of Isis’s escape from the spinning house of Sais had her embark on a journey accompanied by seven scorpions.

After Isis escaped from the spinning house, Thoth warned her to evade Set until Horus came of age to challenge him for the throne. Isis, Horus, and seven scorpions (manifestations of the scorpion goddess Serqet) departed immediately.[29]

This scepter ornament (663-346 BCE) merges the imagery of Isis with that of the scorpion goddess Serqet.

The Walters Art MuseumCC0The group traveled furtively, always moving in order to remain ahead of Set. One day, a rich woman saw Isis and her group approaching her house and quickly shut her doors, denying them any opportunity for charity. Resigned, Isis continued on.

Her scorpions, however, were vengeful, and plotted to make sure the woman would be punished for scorning the goddess. Six of the seven imparted their venom into the one called Tefen. That night, Tefen snuck into the rich woman’s house and stung her child.

The child awoke in agony, and his mother rushed to find help. As she ran through the town, the woman found that everyone ignored her cries. The defeated woman recognized the cruel irony of her plight, for she had committed the same moral failing earlier that day.

Isis heard of the child’s ailment and knew what her scorpion escorts had done. Upset that the innocent child had been targeted, she set out to heal him.

When Isis arrived, she spoke the true names of each of the seven scorpions and commanded the poison to leave the child. Names were routinely invoked as a source of power in Ancient Egypt, and the ritual used here mirrored Isis’s call to remove the poison from Ra. Intriguingly, this story suggests that Isis needed to know Ra’s true name in order to heal him, as the poison she had used was made from his essence.

Isis and the Ascendancy of Horus

When Horus finally came of age, he challenged Set for his kingship. The story has two different versions: an epic version, not unlike an Egyptian version of Homer’s Odyssey, and a satirical (or parody) version. There is no evidence to suggest the latter version developed after the epic version, nor that it was taken less seriously.[30]

Isis in the Epic Version

In the epic tale, Isis supported her son Horus’ quest for the crown. She gilded his boat with gold, and prayed for a successful outcome in his upcoming battle with Set.

At one point, Horus gained the upper hand over his evil uncle, and took him prisoner. Horus asked Isis to guard Set while he pursued his uncle’s fleeing army. Set exploited his position as Isis’s brother, however, and convinced her to free him out of familial obligation.

When Horus returned and learned of Isis’s betrayal, he sliced her head off with a single, mighty blow. Killing gods was a challenging task, however, and Thoth was able to replace Isis’s head with the solar disk and horns of Hathor.[31]

Isis in the Satirical Version

Unlike the martial combat of the epic version, the satirical version was framed as a courtroom drama. As before, Horus challenged Set for the throne. This time, however, Atum-Ra presided as judge over the affair.

Atum-Ra was reluctant to award the throne to Horus, despite the fact that he was the last legitimate king’s heir. At one point in the trial the case seems to be decided in Set’s favor—at least until Isis turned her fury on the court for their decision. In the face of her maternal rage, the court backpedaled.

The court was nearly ready to give Horus the throne when Set demanded a retrial with Isis barred from attending. Atum-Ra accepted this request, and the next trial was held on an island only accessible via a ferry. The ferryman, Anty (also known as Nempty), was instructed not to allow Isis or anyone resembling her to gain access to the island.[32]

Not one to be deterred, Isis disguised herself as an old woman carrying a jar of barley and wearing a gold ring. The ferryman initially told her he could not bring any women to the island. After unsuccessfully offering him her barley in exchange for a ride, Isis offered the ferryman her gold ring. This time Anty accepted the bribe and brought her to the island.[33]

Once on the island, Isis changed her appearance to that of a comely young maiden. When Set saw her, he came over and suggested that the two become better acquainted physically. Instead of addressing his comment, Isis slyly asked him for some advice.

She explained that her husband had died, and that a stranger came and took her husband’s land and animals and kicked her son off of his father’s land. Set, more interested in bedding the disguised Isis than thinking about the question, quickly answered that it was wrong for the stranger to disinherit the son. At this admission, Isis revealed herself and declared that Set had effectively argued against his own position.[34]

Atum-Ra agreed with Isis, and the court once again looked as though it would award the throne to Horus. Set was not one to give up, however. He proposed a challenge where the two gods would turn themselves into hippopotami and see who could hold their breath underwater the longest.

Concerned that her son might lose, Isis crafted a harpoon out of a bronze ingot and threw it at Set. Unfortunately, she missed her target and hit Horus instead. Just as before, Horus struck his mother’s head off with a single mighty blow. Once again, however, Isis survived decapitation and was apparently no worse for wear.[35]

The court decided that Set and Horus should work out the matter on their own, and Set proposed a truce, inviting Horus to dine with him. After a night of drinking, Horus fell asleep on Set’s bed. Set then attempted to rape the younger god, but Horus awoke just in time to catch Set’s semen in his hands.[36]

Immediately Horus went to his mother and told her about what had happened. Suspecting trickery, Isis cut Horus’ hands off and threw them in the Nile. After using her magic to regrow his severed appendages, she collected some of Horus’ semen and sprinkled it over the plants in Set’s garden.

The next day, Set and Horus once again went before the court. Set declared that he should be king because he had “performed a man’s work” on Horus. Horus denied these claims, telling the court that everything that Set said was a lie. Thoth, in an act of what is possibly the strangest use of magic in all of mythological history, commanded Set’s semen to make itself known. As Horus’ hands had been thrown into the Nile, Set’s seed dutifully emerged from the marshes. Thoth then asked for Horus’ semen to come out, and as Set had eaten some lettuce from his garden that morning, the semen emerged from Set’s belly via his ears.[37]

Isis’s trickery saved her son from an embarrassing legal defeat, and ultimately paved the way for Horus to claim his father’s throne.

Isis and the Rise of Christianity

While Christianity spread across Rome in the 4th century CE, it had arrived in Egypt as early as the 2nd century. One prevailing image of Isis featured her holding/nursing her baby, Horus. Thanks to Isis’s widespread cult, this image would have been recognizable almost anywhere in the Mediterranean.

This 7th century BCE statuette depicts Isis in a classic lactans pose, with baby Horus atop her lap. This imagery bears striking similarities to that of the Virgin Mary, whom Isis predated by several thousands years.

The Walters Art MuseumCC0Given Isis’s popularity, many historians have posited that the Virgin Mary owes much of her religious iconography to Isis. Lactans style imagery, or imagery representing maternal nursing, was cited as a direct link between the two.

Despite the apparent connection between the two figures, modern scholarship has suggested that any “cultic continuity” between them was unlikely.[38] While Marian lactans imagery likely borrowed from a tradition of lactans art rooted in Isis’s cult, this shared iconography did not reflect a deeper connection between the two religious figures.

Pop Culture

Please note that the Islamic jihadist group formerly known as ISIS or ISIL is completely unrelated to Isis and the Egyptian pantheon. The group’s English name originated as an acronym based on a literal translation. In recent years, the jihadist group has undergone several name changes and is now more commonly known as Daesh or IS. Despite the tenuous relationship between ISIS the group and Isis the name, the latter has experienced a steep decline in popularity, dropping from 266 babies per million in 2014 to just 22 per million in 2018.[39]

Isis was a recurring character in the Marvel Comics universe, appearing as a member of the Heliopolitans, who were based on the Egyptian pantheon. She first appeared in Thor #239 in September, 1975.[40]

In Downton Abbey, Isis was the name of a yellow lab. She succeeded a lab named Pharaoh, underscoring her ties to the Egyptian goddess.[41]

Bob Dylan’s song “Isis” made several references to Egypt. While the song itself seemed to revolve around Dylan’s failing marriage, its abstract nature made it difficult to parse.[42]