Ra

Overview

As creator and sun god, Ra was a vital part of the Egyptian pantheon. Throughout countless dynasties, Ra was a constant figure of worship whose role shifted as newer gods were incorporated into the state religion.

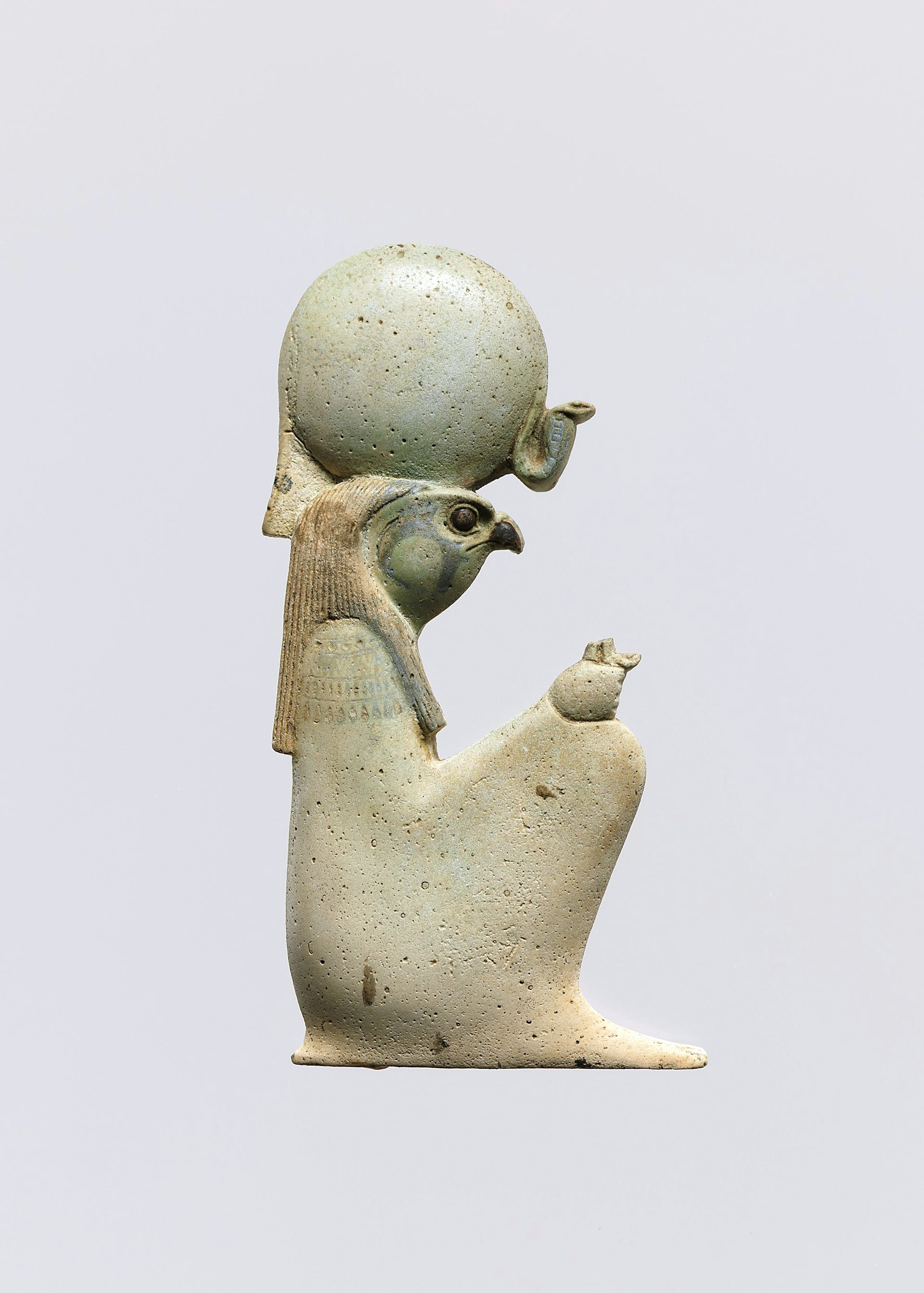

This falcon-headed statuette of Ra-Horakhty (c. 1069–525 BCE) combines the attributes of Ra with those of Horus.

Art Institute of Chicago Public DomainRa had a number of origin stories. He was either self-created, or one step removed from the creation of the universe. No matter the origin story, Egyptian lore held that most of the major Egyptian gods were direct descendants of Ra. The Pharaohs also claimed direct descent from Ra, and used it to justify their rule.

Etymology

In ancient Egyptian, Ra’s name simply meant “sun.” As with many mythologies, Egyptian gods had a multiplicity of names. Ra had many other names, and was sometimes called Re, Amun-Re, Khepri, Ra-Horakhty, and Atum.

Each of these names was typically associated with a different aspect of Ra’s being. Such names often emerged as the Egyptians assimilated new deities and religions into their own.[1]

His worship likely originated in a town the Egyptians called Iunu. The Greeks referred to this place as Heliopolis, or “city of the sun god.” This ancient city was located in what is now a northern suburb of Cairo.

Attributes

While Ra was most famous as the Egyptian creator deity, he fulfilled other roles as well. His other titles included god of the sun, god of kings, and god of order.

Ra could be depicted in a variety of ways. He most commonly appeared as a solar disk—a circle drawn over the head of various sun deities. Ra was also frequently represented as a man with the head of a falcon.

Imagery of Ra often depicted him wielding both a scepter and an ankh.

This small figure (4th century BCE) depicts a crouching Ra with a solar disk upon his head. It once held a scepter in its hand.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainRa, particularly in his morning iteration Khepri, was sometimes depicted as a scarab beetle. The Egyptians would observe the beetle pushing a ball of dung across the sands and burying it before newborn beetles emerged from the earth. This process mirrored the sun’s journey as it traveled across the sky, only to be reborn the next day.[2]

Ra was thought to travel across the sky in his solar barque (boat), which was called Atet.

Family

In an act of auto-procreation, Ra created his children Shu and Tefnut. Shu was the god of the air, while Tefnut was the goddess of mists.

As the god of kings and order, Ra had a special connection to maat, a key mythological concept. Maat was both the Egyptian word for “truth, justice, righteousness, order, balance, and cosmic law,” and the goddess who personified these ideals.[3] The goddess Maat was believed to have been Ra’s favorite daughter.[4] Ultimately, Egyptian rulers were expected to be champions of Maat (both the concept and the goddess), and upon death were judged on how well they had supported her.

Wall painting of Ra and Maat within the tomb of Queen Tausert and King Setnakht, Valley of the Kings.

stigalenas / iStockThough some tales held that Ra created himself (or was created by Amun and Ptah), he did have a mother. Neith, whose name meant “the terrifying one,” was a creator goddess as well as the goddess of weaving.[5]

Family Tree

Mythology

Deciphering Ancient Egyptian mythology has been described as “trying to piece together a jigsaw puzzle when the majority of the pieces are missing and someone has thrown away the box.”[6]

Egyptian religion endured for nearly 3,000 years. As various elements rose and fell during this time, many important myths were merged, edited, and replaced.

While Ra became a pivotal figure in the Egyptian pantheon early on, over time his mythology began to merge with those of other gods, such as Atun, Amun, and Horus.

Origin Myth

In the beginning, the universe was an infinite body of water called Nun (alternatively “Nu”). Nun was unconscious, unthinking, motionless, and eternal.[7]

Amidst this eternal nothingness, Ra willed himself into existence. In what is best understood as an anatomically implausible sequence of events, Ra then created the twins Shu and Tefnut via masturbation. The Book of the Dead described this event:

1248a. To say: Atum [Ra] created by his masturbation in Heliopolis. 1248b. He put his phallus in his fist, 1248c. to excite desire thereby. 1248d. The twins were born, Shu and Tefnut.[8]

In another version of the story, Amun created himself from the primordial void of Nun. With Ptah, the god who “represented the transformative force that turns a creative thought into action and material reality,” Amun created an egg which floated through Nun. Before long, Ra emerged from the egg.[9]

While the stories vary, the basic process of creation in Egyptian mythology was one of differentiation. From a single homogenous state, the universe divided itself into individuals who continued this pattern of division without diminishing themselves in the process.[10]

Creating the Sun, Moon, and Humanity

When Ra created the gods Shu and Tefnut, the world consisted only of infinite ocean and there was no light to see them by. To solve this dilemma, Ra created an eye and sent it out to find his children.

The twin deities Shu and Tefnut adorn this bronze menat (664-380 BCE), an instrument used in religious rit

The Walters Art Museum CC0Upon returning, the eye discovered that Ra had created a second eye for himself in its absence. The first eye became angry, and in order to pacify it, Ra gave it more power than the second. Thus, the first eye became the sun and the second eye became the moon.[11]

Some tales said that after creating the gods and celestial bodies, Ra wept and his tears became humanity.[12] Other versions held that humanity sprung from the tears of the first eye as it wept during its search for Shu and Tefnut. The reason for its weeping was never specified—though it could have been from loneliness or rage upon discovering it had been replaced. A third explanation was that upon his birth, Ra wept because he was alone and could not see his mother, Neith.[13]

The common thread linking these explanations was that humanity always emerged as the “imperfect product of rage and misery,” a classic Egyptian interpretation of the human condition.[14]

Ra’s Curse on Nut and the Egyptian Calendar

Ra’s children, Shu and Tefnut, gave birth to Geb and Nut. Contrary to most mythologies, the male Geb ruled the earth while the goddess Nut ruled of the sky.

Ra expected Nut to be his wife, but she fell in love with Geb and spurned Ra. Furious at this turn of events, Ra placed a curse on her, declaring “that she should not give birth to a child in any month or year.”[15] Meanwhile, the god Thoth had been gambling with the moon over games of draughts (checkers) and had won several times. He took his winnings in the form of the moon’s light, totalling 1/72nd of her illumination. Altogether, he had accumulated an additional 5 days.

The Egyptian hieroglyphic calendar as depicted on the walls of the Temple of Kom Ombo.

Stravaiger CC BY-ND 2.0The Egyptian calendar year only consisted of 360 days and the additional five days were simply added to the end of the year to bring the Egyptian calendar and the solar calendar into agreement. As a result, the extra five days that Thoth had won did not fall under the auspices of Ra’s curse. When the intercalated days finally arrived, Nut gave birth to Osiris, Horus, Set, Isis, and Nephthys.[16]

Ra’s secret name

The Egyptians believed that names held power, so much so that gods went by pseudonyms to keep their power safe. It was for this reason the goddess Isis embarked on a mission to discover Ra’s secret name.

By this time, Ra had grown old and feeble; he napped and drooled as he sat upon his throne. Surreptitiously, Isis collected some of this drool and combined it with a handful of earth. Using her magic, she shaped this mixture into a venomous snake.[17]

Ra was a creature of habit, and strolled the same route each day to survey his creation.[18] Isis set the snake loose at a crossroads and waited. The snake struck as soon as Ra had arrived at the crossroads. While Ra was normally immune to such attacks, this poison had come from his own being, and as such he had no immunity to it and was beset by great pain.[19]

Now in great agony, Ra called his followers and told them he had been grievously wounded. He asked if any of them could offer a cure, but none could give him what he sought.

After all of the others had tried and failed, Isis told Ra she could help him, provided that he told her his true name. Sensing there was trickery at play, Ra answered:

I am the maker of heaven and earth, I am the establisher of the mountains, I am the creator of the waters, I am the maker of the secrets of the two horizons. I am the light and I am darkness, I am the maker of the hours, the creator of days. I am the opener of festivals, I am the maker of running streams, I am the creator of living flame. I am Khepri in the morning, Ra at noontime, and Atum in the evening.[20]

Unimpressed with his prevarications, Isis insisted that without his true name she could not cure him.

Wracked with pain, Ra eventually conceded and told Isis his true name. Reciting a magical incantation, Isis dispelled the poison from Ra’s body. In exchange for her ‘help,’ she demanded that Ra give her yet-to-be-born son Horus both of his eyes: the sun and the moon.

When Horus was old enough, he took over Ra’s position as sun god, allowing the elderly deity to retire from his tiresome daily responsibilities.[21]

This story was recorded on a papyri (a document written on papyrus) from the 20th Dynasty (circa 1200-1085BCE), and was purported to be a spell used to cure snake bites. Egyptian priests believed the spell Isis used to cure Ra would also cure a human victim.[22]

Ra, the Composite God

The Egyptian religion was extremely long lived, and over the span of thousands of years changes were made to it as different groups rose to or fell from power. From the religion’s foundation onward, Ra had always been an important deity; this central status made him a popular candidate for combining with emergent deities.

Ra has been merged so many different times that mentions of a singular Ra are now relatively uncommon.[23]

Ra-Horakhty / Ra-Herakhty

Horus and Ra were conflated early on in the development of the Egyptian religion. The name Ra-Horakhty meant “Ra-Horus of the Double Horizon” and signified the sun conquering its enemies during the night so that it could rise again.[24]

Horus was a complicated god, and had no fewer than 15 forms associated with him. Of these forms, the most consistent (and popular) was the falcon. Ra-Horakhty blended the imagery of Ra and Horus, taking the form of a falcon crowned by a solar disk or, alternatively, a winged solar disk.[25]

Amun-Ra

Around 2020BCE, the Theban ruler Mentuhotep II overthrew the Heracleopolitan dynasty and unified Egypt under his rule. This marked the beginning of what is now known as the Middle Kingdom (2066-1780BCE).

Here, Amun-Ra (760-656 BCE) is identified by a crown of tall plumes above a solar disk.

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0Amun was one of Thebes’ most significant gods, and it was during this period of Theban control that Amun transitioned from being a relatively obscure local god to one of great prominence. By the 18th Dynasty (1550-1292) Amun had grown to national significance and fully merged with Ra.[26]

When the two gods merged, most of the myths associated with Ra were rebranded as the mythology of Amun-Ra.

Atum-Ra

Atum was a creator deity similar to Amun. In fact, the legends associated with Amun and Atum often overlapped, and the two deities essentially served as mirrors of one another.

Like Ra, Atum was a solar god, though his role was more specific. Atum represented the elderly component of Ra and personified the setting sun.[27] As the setting sun, he was often juxtaposed with Khepri, the god of the rising sun.

Atum-Ra was regarded as the god of Lower Egypt, while his counterpart Montu-Ra was regarded as the god of Upper Egypt.[28]

Aten-Ra

When King Amenhotep IV took power (Either 1351BCE or 1353BCE), Amun or Amun-Ra was the central deity of the Egyptians. This could be seen in Amenhotep’s name, which meant “Amun is Satisfied.” Five years into his reign, however, Amenhotep changed his name to Akhenaten. His new name meant “One effective on behalf of Aten,” and reflected his efforts to increase the centrality of Aten over Amun.[29]

Prior to Akhenaten’s efforts to promote him as Egypt’s ultimate deity, Aten had been worshipped primarily as god of the solar disk. With Akhenaten in power, Aten was merged with Ra-Horakhty. At the same time, Akhenaten banned the worship of Amun-Ra and discouraged the worship of the other members of the Egyptian pantheon.

This limestone fragment (c. 1350 BCE) describes Aten as "the living Ra Horakhty." The solar disk upon the faclon's head is a commonly used to represent Ra in his myriad forms.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College LondonCC BY-NC-SA 3.0The changes Akhenaten made did not have popular support, and were gradually reversed following his death. Aten would resume his position as an aspect of the sun god, and Amun would likewise return to his role as chief deity of the state religion.[30]

Khepri

Yet another sun god, Khepri was specifically associated with the morning sun. In the legend of Ra’s hidden name, Ra said that he was Khepri in the morning.

Khepri was at times connected with Atum, and in the guise of Atum-Khepri was regarded as the god of personal transformations. These transformations, called kheperu, included the passages from childhood to adulthood and from life to death.[31]

Khnum

The god Khnum was associated with the regular flooding of the Nile River, as well as the First Cataract of the Nile. He was also connected with pottery wheels, hence his epithet: “lord of the wheel.”[32]

Though Khnum’s origins were unclear, it is known that he was only recognized as a creator deity relatively late in Egyptian history. However, his cult persisted until the second or third century CE.[33] Khnum became connected to Ra once he became regarded as a creator deity.

Montu-Ra

Montu was another Theban god who was ultimately blended with Ra. A falcon-headed star god, Montu served as the chief deity of Thebes, and was considered an aspect of Ra from the twentieth century BCE onward.[34]

Montu-Ra was regarded as the god of Upper Egypt, while his counterpart Atum-Ra was regarded as the god of Lower Egypt.[35]

Raet-Tawy

Raet-Tawy was the female aspect of Ra. In classical depictions, she was often adorned with a sun disk and Hathor’s cow-horned headdress.[36].

Pop Culture

The 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark featured Indiana Jones using the Staff of Ra to locate the ark of the covenant.

Jaye Davidson played Ra in the 1994 movie Stargate. The film depicted Ra as an alien who had enslaved humanity.