Xochiquetzal

Overview

Xochiquetzal (pronounced Show-chee-ket-zal) was the Aztec goddess of fertility, sexuality, pregnancy, and traditional female handicrafts such as weaving. She was also heavily associated with the moon and the various lunar phases.

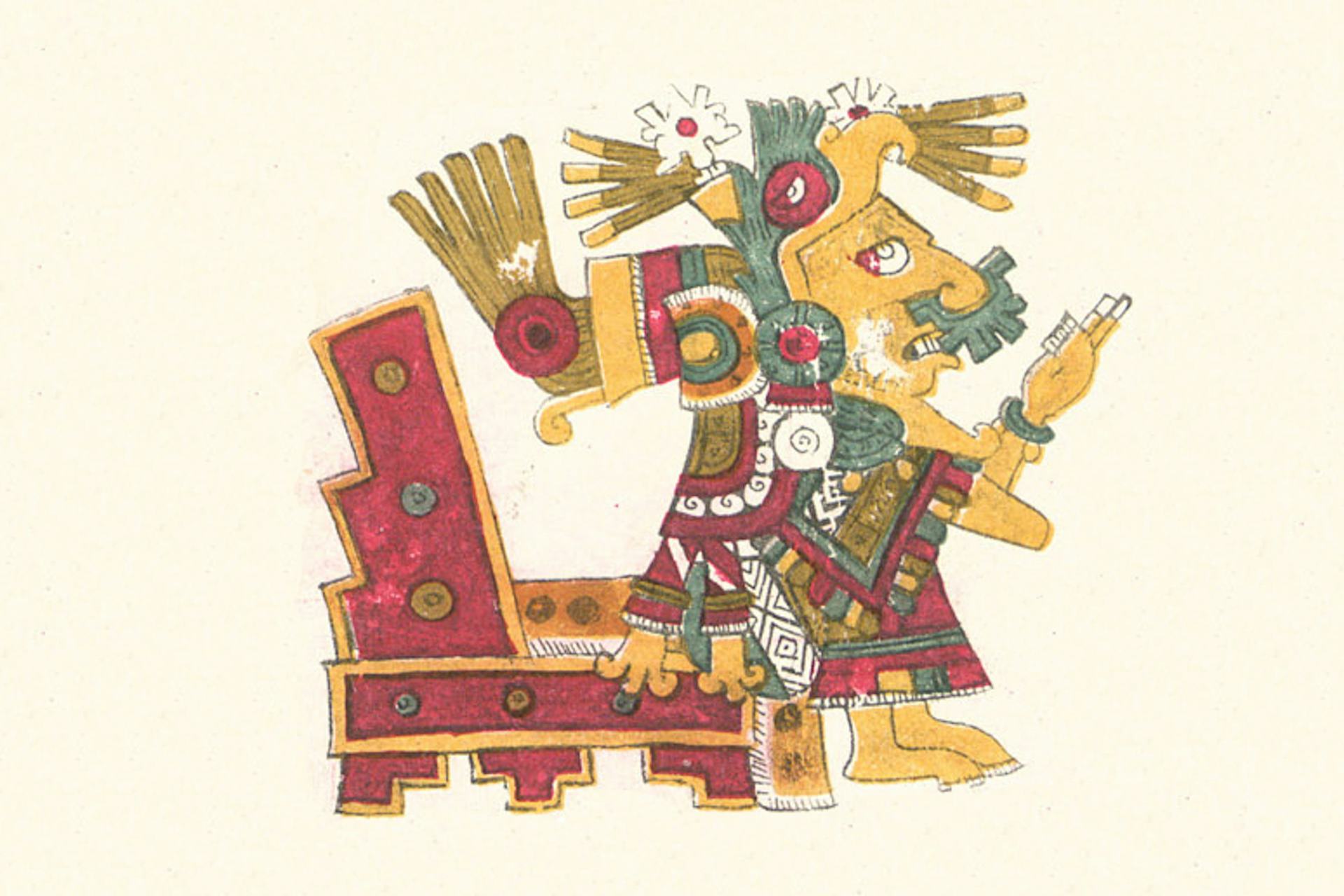

Xochiquetzal as depicted in the Codex Rios c. 1566 CE

Codex RiosPublic DomainEtymology

Xochiquetzal’s name was a combination of the Nahuatl words xochitl, meaning “flower,” and quetzalli, meaning either “Quetzal bird,” or the highly desirable tail feathers of that bird.[1] Taken altogether, her name was often interpreted as “Flower Quetzal Feather.”[2]

Xochiquetzal was also occasionally referred to as Ichpochtli, meaning “maiden” or “young girl.” Though this term did not originally imply anything beyond age, it took on a virginal connotation following the Spanish conquest.[3]

Attributes

Xochiquetzal is unique amongst Aztec goddesses in that she was always portrayed as a young woman. Her peers, like Coatlicue, were usually shown as matrons. In artistic renderings, Xochiquetzal was usually adorned with flowers and shown wearing rich garments.

The link between Xochiquetzal, flowers, and sexuality was not an arbitrary one. Like many other cultures, the Aztecs drew parallels between flowers and the clitoris or vulva.

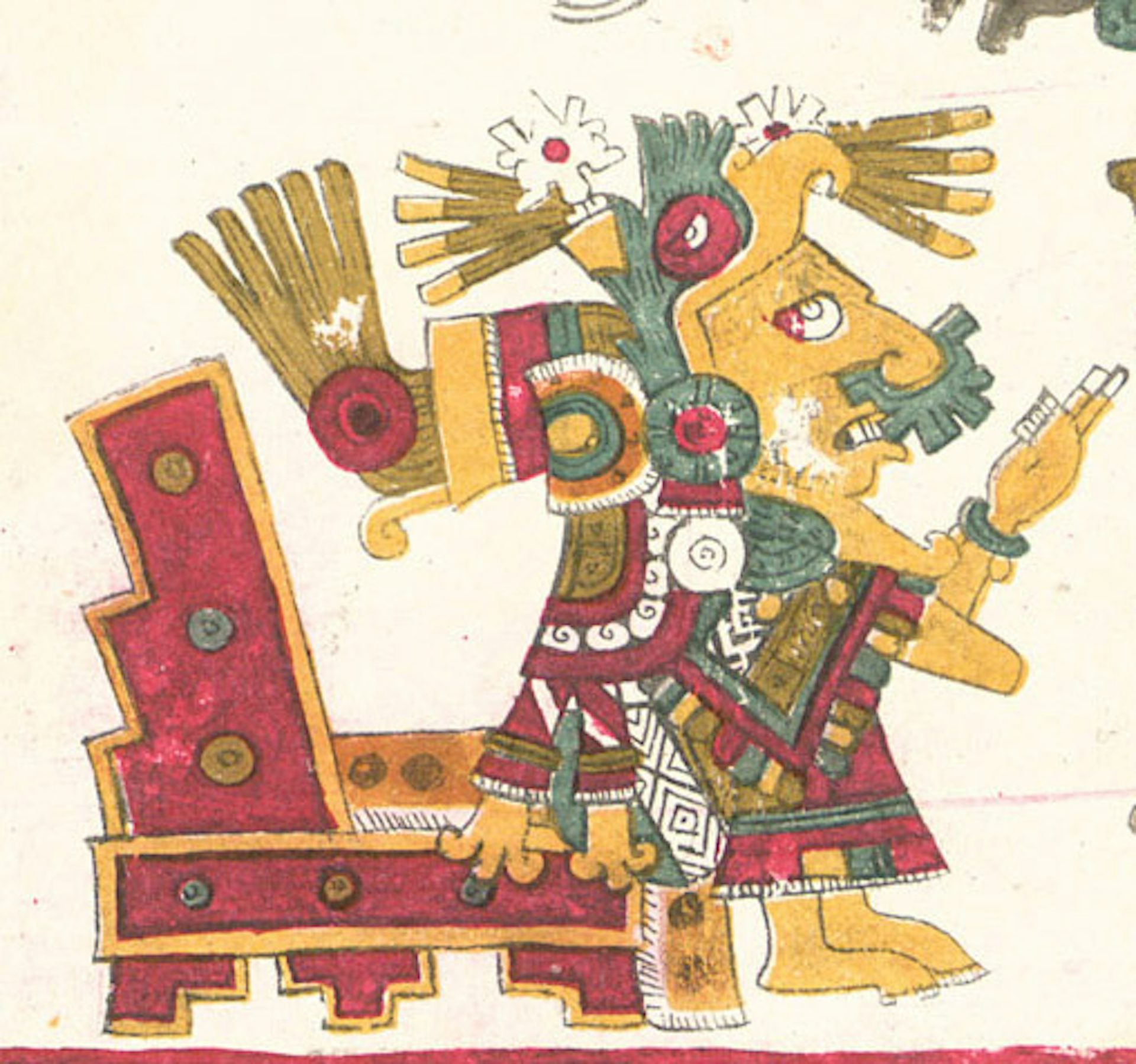

In this piece from the Codex Borgia, Xochiquetzal is adorned with flowers and has a pierced nose. Such features were commonly associated with the goddess.

Codex BorgiaPublic DomainFamily

Xochiquetzal’s familial ties are somewhat mysterious, as her parentage was lost to the historical gaps left by time and conquest. Nevertheless, she did have several important relations. Her twin brother Xochipilli was the god of art, beauty, and dance. Like his sister, Xochipilli has been interpreted as a god of erotic love. Unlike his sister, Xochipilli represented male prostitutes and homosexuality.

Xochiquetzal played wife to many different Aztec gods. Such gods included:

Piltzintecuhtli – god of the rising sun, healing, and hallucinogenic drugs[4]

Tlaloc – god of rain

Tezcatlipoca – one of the four creator deities who served as omnipresent god of the night sky and knower of all thoughts

Centeotl – god of maize

Xiuhtecuhtli – god of fire and heat

Family Tree

Siblings

Brother

- Xochipilli

Consorts

Husbands

- Tlaloc

- Tezcatlipoca

- Piltzintecuhtli

- Centeotl

- Xiuhtecuhtli

Mythology

Though Xochiquetzal is one of the oldest Aztec gods, her origin story remains unclear. She was an important member of the Aztec pantheon and one of several literal and figurative mothers to the Aztec people. A recurring element in Xochiquetzal’s legends was her relation to the moon. Such relations changed depending on the myth being told, however, as she would reflect different aspects of the lunar cycle in each tale.

Origin Myth

While many Aztec gods had explicit origin stories, Xochiquetzal did not. While it was possible that the Aztecs lacked an origin story for her, it is more likely that it has simply been lost to time and conquest. Xochiquetzal was said to have come from Tamoanchan, the ancestral origin place of the Aztec gods.[5] Her connection to Tamoanchan hinted at her enduring status in Mesoamerican religion; Tamoanchan was not a Nahuatl word, but a Mayan one.

This Mayan figurine (c. 600-900 CE) may depict the lunar deity known as Goddess I.

Simon BurchellCC BY-SA 3.0The Mayan equivalent to Xochiquetzal was Goddess I, a deity that represented fertility, procreation, erotic love, and weaving. Like Goddess I, Xochiquetzal was associated with a lunar cult, though there is some ambiguity as to which phase of the moon she represents.

The goddess of the moon moves swiftly across the sky...seemingly visiting different planetary lovers along the way, before returning to stay with her solar husband for several days each month. - Susan Milbrath[6]

Xochiquetzal and the Creation of the Second Woman

During their quest to create the universe, Xipe Totec, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Huitzilpochtli created the first man and woman. When their son Pilcetecli came of age, however, there was no one for him to marry. Seeing that this problem needed to be remedied, the gods “made of the hairs of Suchiquecar [Xochiquetzal], a woman with whom his first marriage took place.”[7]

Flowers for the Land of the Dead

One Aztec legend described the risqué origins of bats and how they, along with an unwitting Xochiquetzal, were responsible for Mictlan’s foul odor.

The first bat was born when Quetzalcoatl’s semen dripped onto a rock while he was washing. The gods sent the bat to bite out the vulva of the young goddess Xochiquetzal, from which they grew nasty-smelling flowers to present to Mictlantecuhtli.[8]

In some Aztec stories, Xochiquetzal was the wife of the sun, which would spend the night traveling through Mictlan before returning the next day. This connection could explain Xochiquetzal’s involvement in this odd tale.[9]

Pregnancy, Erotic Love, and Weaving

At first glance, the conjunction of pregnancy, erotic love, and weaving seem like a relatively random assortment of concepts. However, these relations make more sense when one considers Aztec symbolism.

Pregnancy and weaving were connected through the idea of a spindle. As a weaver worked, the spindle gradually became more round. As a pregnancy progressed, the mother-to-be’s belly would grow rounder as well. As a lunar deity, Xochiquetzal had an additional link to pregnancy; the moon also grew rounder over the course of its cycle.

Weaving and erotic love were also connected. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, weavers had a reputation for being loose women. Xochiquetzal had something of a reputation for being a seductress—seducing the virtuous Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl among others.[10]

The Festival of Hueypachtli

Hueypachtli, sometimes called Tepeilhuitl, was an annual festival held primarily to honor Tlaloc; Xochiquetzal’s cult also partook in the celebrations.[11] During this festival, Xochiquetzal was “honored with flower offerings, drinking, and ‘fornications.’”[12] As was common in Aztec festivals, an ixiptlatli or impersonator was chosen to represent Xochiquetzal.

The ixiptlatli was a young woman who would be decapitated and flayed. A man was selected to wear her skin and weave (an act typically reserved for women) in a representation of “the gender ambiguity embodied in the cult of lunar deities.”[12]

Xochiquetzal, Yappan, and the Origin of Scorpions

Much like the Biblical Eve, Xochiquetzal was the first woman to sin in Aztec mythology. In line with her licentious reputation, Xochiquetzal seduced her brother Yappan, who had taken a vow of chastity. Xochiquetzal went unpunished for her actions while Yappan was turned into a scorpion for his insolence.[13]

Pop Culture

The Mexican artist Rurru Mipanochia named her 2017 art exhibit Xochiquetzal: Erotismo y Procreation after Xochiquetzal. Her work embraced the “gender and sexual emancipation of millennial Mexico City,” and the freedom to choose one’s own sexuality without concern for conservative social mores. As the goddess of eroticism and female sexual power, Xochiquetzal was uniquely suited to represent Mipanochia’s work.[14]