Quetzalcoatl

Overview

Quetzalcoatl (pronounced Ket-zal-ko’-wat) was the Aztec version of the Feathered Serpent god that permeated Mesoamerican mythologies. Though he originated as a vegetation god, Quetzalcoatl’s role in the Aztec mythos expanded over time.

By the time the Spanish arrived in the New World, Quetzalcoatl was regarded as the god of wind, patron of priests, and inventor of calendars and books. He was also occasionally used as a symbol of death and resurrection.

Etymology

Quetzalcoatl’s name, which means “Feathered Serpent,” was derived from the Nahuatl words for the quetzal bird and “coatl,” meaning serpent. Unlike the newer gods of the Aztec pantheon, Quetzalcoatl shared his namesake with the feathered serpent deities of the K’iche’ Maya and the Yucatec Maya. The name of the K’iche’ Maya deity Q’uq’umatz meant “Quetzal Serpent” while the Yucatec Maya god Kukulkan translated to the less specific “Feathered Serpent.”

Attributes

The Feathered Serpent deity common to much of Central America first appeared in images, statues, and carvings starting around 100BCE.[1] Depictions of the Feathered Serpent usually took the form of a carved snake head placed upon a wall, with further relief carvings depicting feathers or birds. These carvings also included a conch shell, which was a symbol of the wind.

A typical portrayal of the Feathered Serpent. The head was carved separately and attached to the wall via tenons (mounting pegs).

Jami DwyerCC BY-SA 2.0Starting around 1200CE, the manner in which Quetzalcoatl was depicted began to change. From this point on, he was usually portrayed as a man wearing a conical hat, conch shell pectoral brooch, shell jewelry, and red duck-billed face mask.[2]

Family

Quetzalcoatl was the third son of the dual creator god Ometeotl. His older brothers were Xipe Totec and Tezcatlipoca while his younger brother was Huitzilopochtli.

Other legends posited that Quetzalcoatl was the son of the goddess Chimalma. While these stories vary, some said Mixcoatl (the Aztec god of the hunt) impregnated the goddess Chimalma by shooting an arrow from his bow.

In this legend, Mixcoatl shot at Chimalma for spurning his advances. Chimalma caught the arrows in her hand, however, which is how she got her name (which means “Shield Hand”). Chimalma later married Mixcoatl, but the two were unable to conceive. After praying at an altar to Quetzalcoatl and swallowing a precious stone (emerald or jade, depending on the version of the tale), Chimalma became pregnant with Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl. Also called One-Reed and Ce-Acatl, Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl founded a dynasty that would last until 1070CE.[3]

Family Tree

Parents

Fathers

Mothers

- Ometeotl

- Chimalma

Siblings

Brothers

Mythology

Quetzalcoatl’s role in the Aztec cosmology was complex and multifaceted. While he was responsible for creating humanity and providing them with their staple crops, it was his brother Tezcatlipoca that ultimately ruled the modern era. As with many of his peers, Quetzalcoatl’s role has been revised throughout history and was altered to better suit the sensibilities of contemporary Spanish writers, who were trying to comprehend an entirely different way of thinking. Quetzalcoatl was sometimes portrayed as a trickster god, and while his plans did not always work as intended, they did consistently benefit humanity.

The Creation of the World

As one of the four sons of the Aztec creator deities Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, Quetzalcoatl played an integral role in the creation of the universe. After he was born, he and his family waited 600 years for his youngest brother, Huitzilopochtli (who was born without flesh), to join them in the process of cosmic construction.

Quetzalcoatl and either Huitzilopochtli or Tezcatlipoca (depending upon the myth) were responsible for the creation of the cosmos. After creating fire, they molded a partial sun and gave life to the first man and woman.[4]

Quetzalcoatl as depicted in the 16th-century Codex Borbonicus.

Codex BorbonicusPublic DomainIn many versions of the myth, Quetzalcoatl worked in opposition to his brother Tezcatlipoca. This rivalry was a recurring theme in Aztec mythology, with the flying serpent (Quetzalcoatl) frequently pitted against the black jaguar (Tezcatlipoca).

Each bout of fighting brought one of the four epochs of Aztec history to an end, ultimately ending with Tezcatlipoca in control of the fifth (and current) age.[5] During this time, it was conceivable that Quetzalcoatl could defeat his brother once more and regain power. This possibility would become mythologically significant when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 16th century.

Stealing Bones from the Underworld

Quetzalcoatl was instrumental in creating people to populate the fifth age. In order to do this, Quetzalcoatl had to sneak into the underworld of Mictlan and trick Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl, the Lord and Lady of Death, into giving him the bones they guarded. Mictlantecuhtli would only give the bones to Quetzalcoatl if he could create a sound by blowing into a conch shell with no holes in it. Quetzalcoatl managed to complete this challenge through clever trickery. He had worms drill a hole in the conch, then filled the shell with bees. Quetzalcoatl’s actions successfully tricked Mictlantecuhtli into giving him the bones. But this was not enough for Quetzalcoatl. In an effort to further trick Mictlantecuhtli, Quetzalcoatl told him that he would leave Mictlan without the bones.

Before Quetzalcoatl could escape from Mictlan, however, his deception was discovered by Mictlanecuhtli. A deep pit appeared before Quetzalcoatl, preventing his escape. As he fell into the the pit, Quetzalcoatl was knocked unconscious and mixed up the bones he was carrying. After his eventual escape, Quetzalcoatl combined the now slightly shuffled bones with his blood and corn to create the first humans of the fifth age.[6] The Aztecs used this allegory to explain why people came in all different heights.

The Discovery of Maize

According to legend, the Aztec people initially only had access to roots and wild game. At that time, maize was located on the other side of a mountain range that surrounded the Aztec homeland. Other gods had already attempted to retrieve the maize by moving the mountains, but their efforts had all been unsuccessful.

Where others had approached this problem with their brute strength, Quetzalcoatl chose to rely on his sharp mind. He proceeded to turn himself into a black ant and followed the other ants over the mountains. After a long and difficult journey, Quetzalcoatl reached the maize and brought a kernel back to the Aztec people.[7]

Other versions of the legend featured Quetzalcoatl discovering a great mountain of seeds that he could not move by himself. He instead solicited the help of Nanahuatzin, who destroyed the mountain with lightning. With the seeds laid bare, Tlaloc, a rain god often associated with Quetzalcoatl, proceeded to snatch them up and scatter them across the land.[8]

The Fall of Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl

The ruler Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl (also known as One-Reed) was famous for his wise rule. Under his guidance, the capital city of Tula became incredibly prosperous. Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl maintained order across his domain and even eschewed the practice of human sacrifice.

While many were happy with Quetzalcoatl’s reign, his rival Tezcatlipoca was not and plotted to bring him low. One night, Tezcatlipoca plied Topilitzin-Quetzalcoatl with pulque (an alcohol made from agave); afterwards, the drunken ruler slept with his celibate priestess sister. Ashamed of what he had done, Topilitzin-Quetzalcoatl departed Tula and set out for the sea.

It is uncertain what happened next. Some versions held that Quetzalcoatl cremated himself; others stated that he spent eight days in the underworld before reemerging as Venus or the morning star. Yet another version of this tale had Quetzalcoatl parting the sea and leading his followers in a march along the ocean floor. This version’s blatant mirroring of the story of Moses was almost certainly a product of later Spanish influence.[9]

Cortes: The Second Coming of Quetzalcoatl?

The Aztec believed that Tezcatlipoca ruled of the fifth age, and while they thought that the fifth sun was the last sun, it was not a foregone conclusion that Tezcatlipoca would remain in charge. If Quetzalcoatl did return, however, how would he be known? This question was most likely on Emperor Moctezuma II’s mind when he received word in 1519 that the Spanish had arrived via the eastern coast. The return of Topiltzin-Quetzalcoatl, who had departed to the east by sea, certainly seemed like a possibility to the Aztec nobility as they considered the arrival of these seafaring newcomers.

Moctezuma sent a gift of food and the ceremonial clothing of four gods (one set of which belonged to Quetzalcoatl) to the newcomers, presumably to ascertain their true intentions. Cortes may have looked the part of a god, what with bearing the conical helmets of the time and arriving via wind-powered sailing vessels, but his actions soon revealed that he was not the morally upstanding Quetzalcoatl.[10]

Ultimately, the legend that Moctezuma and the Aztecs believed Cortes to be Quetzalcoatl was a just that: a legend retroactively turned into historical “fact” by Spanish writers. These writers may have misinterpreted a speech Moctezuma gave to Cortes, or simply invented the idea because it fit their historical expectations.

The Wandering Apostle

Quetzalcoatl remained a potent figure well after the Spanish had conquered the New World. The friar Diego de Duran suggested that Quetzalcoatl may have actually been the apostle St. Thomas. The saint had departed from the Roman Empire following the death of Christ, and Duran believed his travels across the sea could explain the elements of Aztec religion that mirrored Christianity. This link to Europe was embraced by 17th-century Mexican nationalists because it meant that their cultural heritage pre-dated Spanish influence.[11]

Pop Culture

The third president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, John Taylor (1808-1887), believed that Quetzalcoatl was Jesus Christ. Taylor wrote that “the story of the life of the Mexican divinity, Quetzalcoatl, closely resembles that of the Savior; so closely, indeed, that we can come to no other conclusion than that Quetzalcoatl and Christ are the same being.”[12] It is unclear how widely accepted Taylor’s argument was amongst the LDS Church, but Quetzalcoatl is not currently an important part of the LDS belief system.

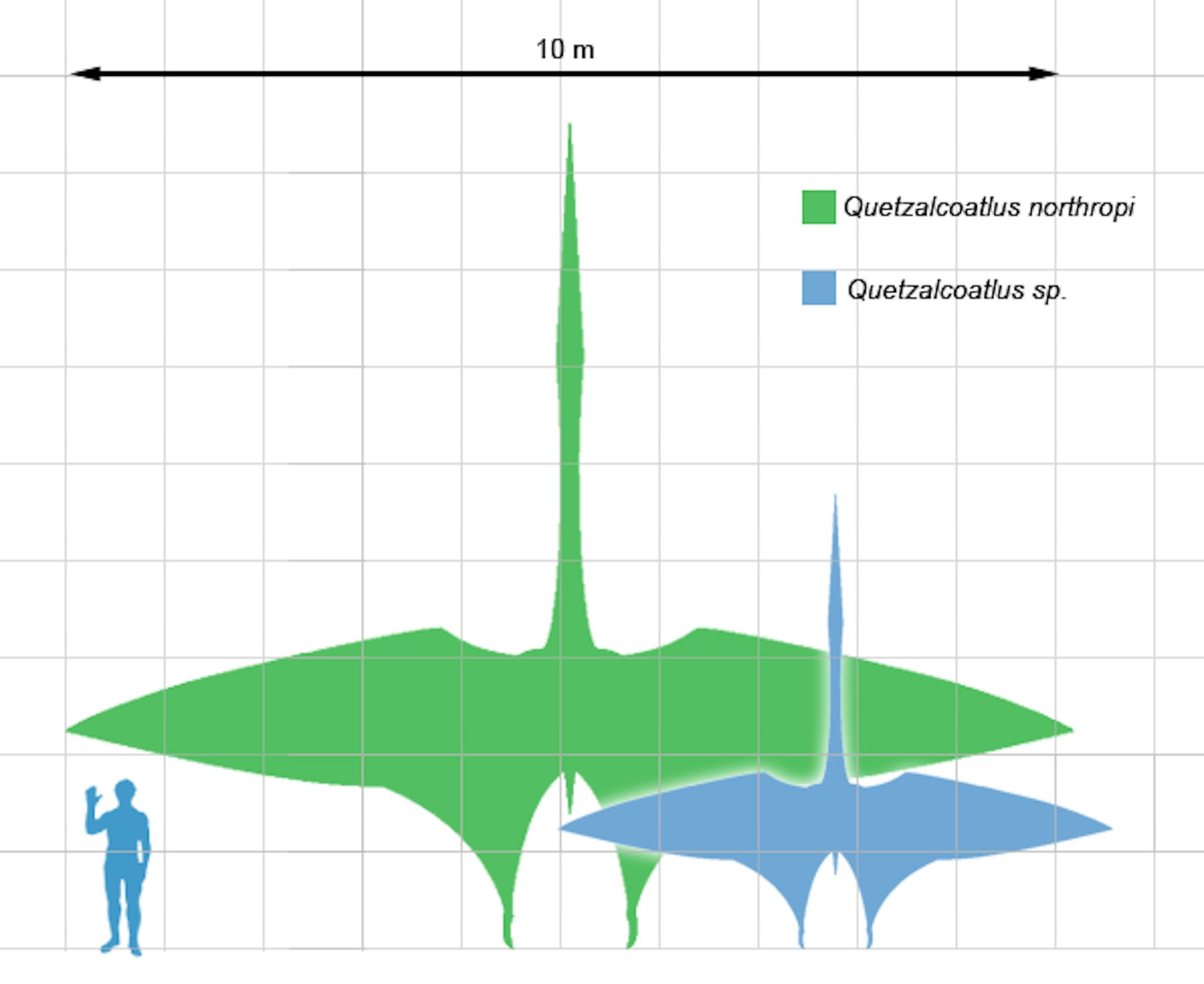

The pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi was named after Quetzalcoatl. First discovered in 1971, Quetzalcoatlus stood nearly 10 feet tall and had a wingspan of at least 36 feet.

Quetzalcoatlus northropi and Quetzalcoatlus sp. (an as of yet unnamed species) were large creatures with enormous wingspans. Note the human for scale.

Matt Martyniuk, Mark Witton and Darren NaishCC BY 3.0Sir Terry Pratchett’s novel Eric included a parody of Quetzalcoatl in the form of a demon named Quezovercoatl. Quezovercoatl was described as being “half man, half chicken, half jaguar, half serpent, half scorpion, and half mad” for a total of “three homicidal maniacs.”[13]

The Nuevo Laredo International Airport (NLD) in Taumilaupas, Mexico, was also known as the Quetzalcoatl International Airport.

In the Final Fantasy video game series, Quetzalcoatl was a recurring summon or creature. While his artwork changed considerably since he was first included in Final Fantasy VIII, he was consistently portrayed as a flying, lightning-like creature. Quetzalcoatl has appeared in Final Fantasy VIII, XII, and XV, as well as the Final Fantasy trading card game.