Tlaloc

Overview

One of the oldest and most widely worshiped Mesoamerican gods, Tlaloc was the Aztec god of rain and thunder. It was by his blessing that the seasonal rains arrived on time for the vital maize harvest.

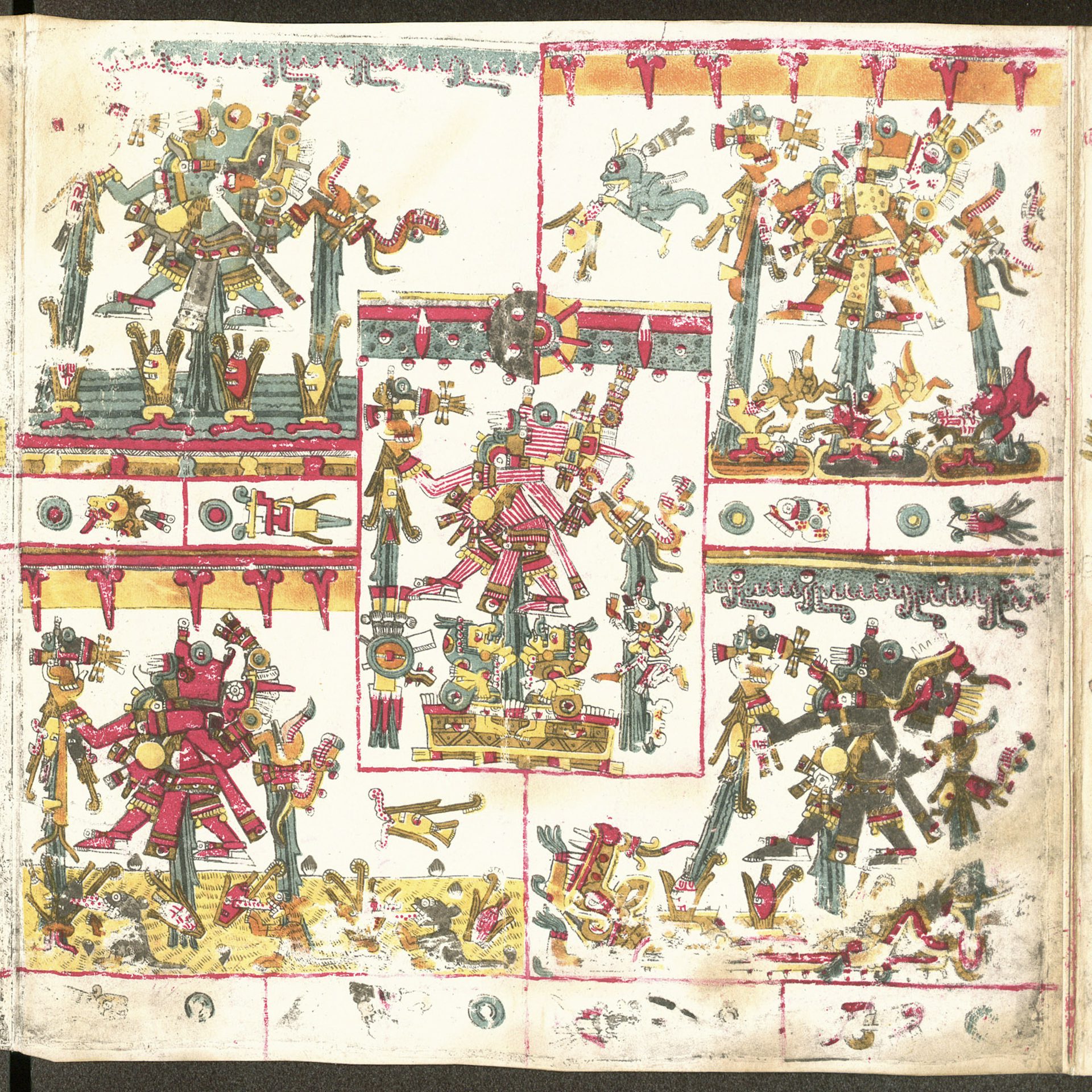

This image from the Borgia Codex depicts Tlaloc in his classical form. Note his "goggle eyes" and large fangs.

FAMSIPublic DomainWhile his rains often brought life to Mesoamerican societies, they could also take it away. If they arrived at the wrong time, or came in the form of intense storms, the rains could ruin crops and cause drought or flooding. Tlaloc is one of several gods the Mexica people refused to fully abandon following the introduction of Christianity, and in many ways his veneration was never completely forsaken.

Etymology

Tlāloc’s name is derived from the Nahuatl word tlalli which means earth, or soil.[1] His name has been taken to mean “in the earth,” perhaps referencing the moisture of soil.[2]

Tlaloc’s alternative names, Tlamacazqui and Xoxouhqui, reflect his role as a life-providing rain god, meaning “Giver” and “Green One” respectively.

Attributes

Tlaloc is one of the most ancient Central American gods with identifiable records of his worship dating back to 100BCE. These earliest images of Tlaloc were found on vases in Tlapacoya and bore his visage alongside lightning bolts. While we cannot say for sure what Tlaloc’s role was at this earliest stage, or even what he was called, the imagery used to depict him remained remarkably consistent even over long spans of time.

This small vessel (c. 550-650 CE) incorporates Tlaloc's head into its design.

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0Tlaloc is most often depicted with rings around his eyes, sometimes described as “goggle” eyes, and pointed fangs. Images of Tlaloc usually fall into one of two categories: Tlaloc A is shown with “a five-knot headdress, [a] water lily in the mouth, [a] staff and vessel, and [a] year-sign headdress,” while Tlaloc B has “a long bifurcated tongue, [only] three or four small fangs, and a headdress with a zigzag band and three pendant elements.”[3] Both of these categories retain the “goggle” eyes and pointed fang that help define Tlaloc’s appearance

Another element of Tlaloc’s multiplicity are the Tlaloques. These “little Tlalocs,” were guardians of the four cardinal directions (North, South, East, and West) and held up the sky.[4]

The god Chac serves as Tlaloc’s equivalent in the Mayan pantheon. Like Tlaloc, Chac was the god of lightning and rain, and existed “both individually and as a set of four gods, one for each cardinal direction.”[5]

Family

While many of the Aztec gods have traditional parentage, Tlaloc and his wife Chalchiuhtlicue were created either by all four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl (Xipe Totec, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Huitzilopochtli), or by Quetzalcoatl and Huitzilopochtli.[6] Tlaloc’s son, Tecciztecatl, would become the moon after following the god Nanahuitzin into a sacrificial bonfire meant to create the fifth sun.

Some stories say that Tlaloc was initially married to Xochiquetzal, whose name literally means “Flower Quetzal Feather” or “Flower Precious Feather.” She was stolen away from him, however, by Tezcatlipoca.

Family Tree

Parents

Fathers

Consorts

Wives

Children

Son

- Tecciztecatl

Mythology

Tlaloc was an often beneficent - though occasionally fickle - god of water, rain and thunder. The Aztecs offered sacrifices to him to ensure the seasonal rains would arrive on time for a successful harvest.

The Five Tlalocs

As with many Aztec gods, there are multiple Tlalocs. An Aztec story recounts how Tlaloc and his wife resided in a great house with a patio containing a series of pots. The other Tlalocs, or Tlaloques, stood in each corner of the patio and chose which pot to break. Each pot was filled with a different type of water which, when broken, would dictate the type of rain the crops would receive.

In this page from the Codex Borgia, the Tlaloque can be seen surrounding another, more central Tlaloc.

FAMSIPublic DomainThe Aztecs desired the “fine gentle rains for sprouting crops,” as each of the other types of rain could spell ruin for the harvest. Depending on the legend, these other types of rain would include:[7]

Blighted rain, which would bring fungus and rot

Frost rain

Fire rain or drought

Wind rain

Tlalocan: A Heavenly Paradise

The Aztecs believed that heaven was divided into thirteen levels, with a deity or group of deities associated with each. Tlaloc ruled over the first level, called Tlalocan.

This mural at Teotihuacan, commonly known as the "Paradise of Tlaloc", depicts the Aztec worship of water. The piece features a mountain with water pouring from its summit. The flowing waters are filled with fish and irrigate the surrounding fields.

iStockIn general, the various levels of heaven were reserved for those who died violent deaths; Tlalocan was no exception. Those who experienced a water-related death such as drowning, getting struck by lightning, or succumbing to a water-related disease would end up in Tlalocan. Those who died due to physical deformities associated with Tlaloc would also find themselves in his realm. Tlalocan itself was depicted as a verdant landscape replete with edible plants; the realm existed in perpetual springtime.[8]

The Temple atop Mount Tlaloc

In order to secure the rain their crops needed, the Aztecs offered annual sacrifices at a temple atop Mount Tlaloc. Notably, the sacrifice victims for these ceremonies were children. In most cases these children were richly adorned, and “their tears were viewed as positive signs of imminent and abundant rain.”[9]

Mount Tlaloc is the ninth tallest mountain in Mexico and the tallest within the Sierra de Rio Frio range.

Miguel Angel Huicochea MaldonadoCC BY-SA 2.0The mountaintop temple, which was also likely used for astrometric and meteorological observations, was torn down after the Spanish conquest. In addition to a key temple location, the mountain offered the Aztec panoramic views of the east, allowing them to note changing weather patterns and forecast the rains their freshly-planted crops would require.

Worship

While many Aztec gods live on in works of fiction, or may even continue to exist as cultural icons, Tlaloc seems to have persisted in a more substantial fashion.

Piedra de los Tecomates

In the town of San Miguel Coatlinchan (sometimes just called Coatlinchan) a massive statute of Tlaloc was discovered in the late 1880s. The monolith was identified as Tlaloc in 1903, and locals soon began venerating it as a symbol of the deity. The locals referred to this monolith as Piedra de los Tecomates, named after its gourd-like crevices. The statue was regarded as having prophetic powers: water accumulating in the tecomates indicated forthcoming rain. Additionally, the accumulated water itself was regarded as having curative powers.[12]

In 1963, the 168-ton statue was relocated to Mexico City during the dry season. Allegedly, on the day the statue arrived in Mexico City, “the heaviest thunderstorm ever recorded during this time of year swept over the valley. Incessant rain poured from the sky for days in what some claimed could only be a supernatural event.”[13]

Monolith statue of Tloloc at Chapultepec Park, near the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Mexico.

David Ramirez 2814The statue can still be visited in Chapultepec Park, Mexico City.

Tlalocan: A Temple Rebuilt

The temple atop Tlalocan was destroyed, likely by the Spanish Inquisition or their supporters, during the early 1500s. The archaeological record shows that, following the temple’s destruction, the mountaintop went seemingly unused for centuries. That changed in the 20th century, however, when a research group discovered that a small temple had been rebuilt sometime between 1957 and 1982.

Pop Culture

The artist Jesse Hernandez has released several pieces dedicated to Tlaloc. The first came out in 2008 and was a 16” Qee painted with classic Tlaloc inspired motifs. In 2018 he designed a limited edition Dunny (a type of collectible vinyl art toy) that resembled Tlaloc.